These memoirs were collected by Liliana Marconi.

“I was twenty years old on June 10th, 1940, when the war broke out and I found myself already on June 16th on a mission as a torpedo man of a crew of 7 officers and 50 non-commissioned officers and sailors, on the submarine “Console Generale Liuzzi” of the Italian Royal Navy, sunk in combat on June 27th, 1940.

My unit had been assigned to operate in the eastern Mediterranean, in a patrol area off Famagusta, between Alexandria, Egypt, where the British base was located, and Ismailia, with the task of attacking enemy ships sailing between Cyprus, Syria and Egypt. After 9 days of mission, on June 25th we were ordered to transfer to the Atlantic Ocean. In fact, our submarine was ocean-going and was one of the largest: we had a cannon, a machine gun and 16 torpedoes on board.

Towards dusk, between Cyprus and Heraklion we were sighted by 5 British destroyers. I was in the bow when I heard the alarm siren. We descended with a rapid dive to 100 meters but were charged with ten depth charges. Then we continued to descend to a depth of 120 meters and another charge of ten bombs arrived: 180 kilos of TNT each. It was the end of the world. We continued our descent to 150 meters, but more bombs arrived: we counted a total of 60.

The submarine was by then unmanageable, all the instruments on board were destroyed as well as most of the equipment. Our commander, Lieutenant Commander Lorenzo Bezzi, when we were already at a depth of 190 meters, decided to surface. The situation was very critical: immersed in total darkness, with broken and overturned equipment; A scary thing.

The captain with the chief engineer gave the order to emerge and since we were no longer able to defend ourselves, once we emerged, he ordered us to get out of the submarine through the conning tower because the submarine was now about to sink. We, who were in the bow, came out last. Then the captain ordered us all to jump into the sea because no one wanted to abandon the submarine. With his order “Throw yourselves all into the sea” we were forced to obey and jump into the water. Immediately some destroyers bombarded us with a couple of cannon shots: one hit the bow. The captain, when he saw that we were all at sea, returned to the interior of the submarine and locked himself in it, going to the bottom with it.

He was decorated with the gold medal for military valor and the Non-Commissioned Officers’ School of Taranto, which is the most prestigious in Italy, bears his name in his honor: Lorenzo Bezzi.

Those who were close to the destroyers were taken on board and made prisoners. We, on the other hand, who were in a more distant area, were not spotted immediately and I remained in the water for almost 5 hours. By then it was night: a stormy sea was pushing me up and down and I did nothing but pray to God and Our Lady. I felt that my strength was leaving me, I was exhausted, and I couldn’t take it anymore: when I already thought I was going to die, I saw a large shadow approaching; It felt like a mountain, and I lost consciousness.

Instead, it was a destroyer that rescued me and took me on board: I regained my senses while they revived me. The doctor gave me injections and I realized that only three of us survived. I still remember the words of my companion who said to me: “Come on De Montis, we are safe.”

They disembarked us in Alexandria, Egypt, and from there took us to Ismailia near Suez as prisoners of war; after four months they took us to India, about a hundred kilometers from Bombay, where I spent 5 years of captivity: 5 years behind a fence is very hard! It was not life… It seemed like these years would never end.

During my imprisonment in India, I always asked about a friend who had been on board the Tigre and was in Ethiopia at the time. His name was Novario Mura and I learned that he had also been captured and that he was in the prison camp located in front of mine, at a distance of about sixty meters. I immediately ran and looked for him and found him, but to my great amazement he did not recognize me immediately. I had to remind him who I was, but he remained almost indifferent and told me that he could not believe what I said, because he had learned from the newspapers and from the family that I had died in the sinking of the submarine. It took a while to convince him that it was me, his great friend of all time, and that fortunately I had survived.

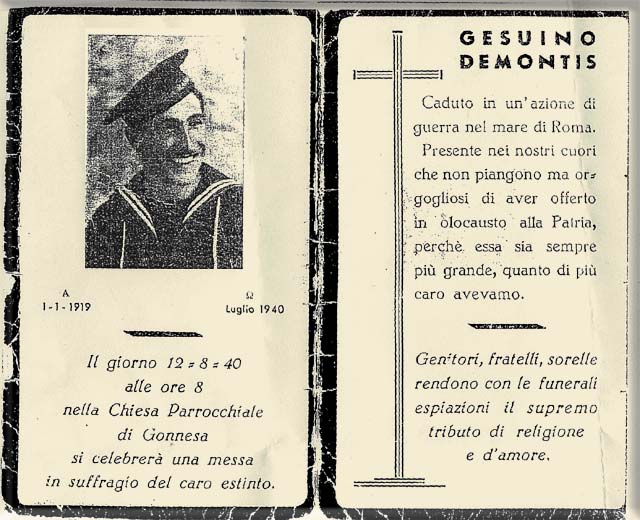

The funeral program mentioned in the interview

Novario then told me of the great pain of my family and of the Mass in suffrage that they had celebrated on August 12th, 1940, during which, according to custom, they gave all those present the funeral program with my photograph. When I returned home, after having communicated by letter that I was still alive, no one told me that they had believed me to have died in combat, but I found – kept in a drawer – the program that had been given during the Mass in my suffrage and which bore these words:

“Gesuino Demontis, fallen in an action of war in the sea of Rome. Present in our hearts that do not weep but proud to have offered as a holocaust to the Matherland, so that it may be ever greater, what we held dear. Parents, brothers and sisters render with their funerals expiation the supreme tribute of religion and love.”

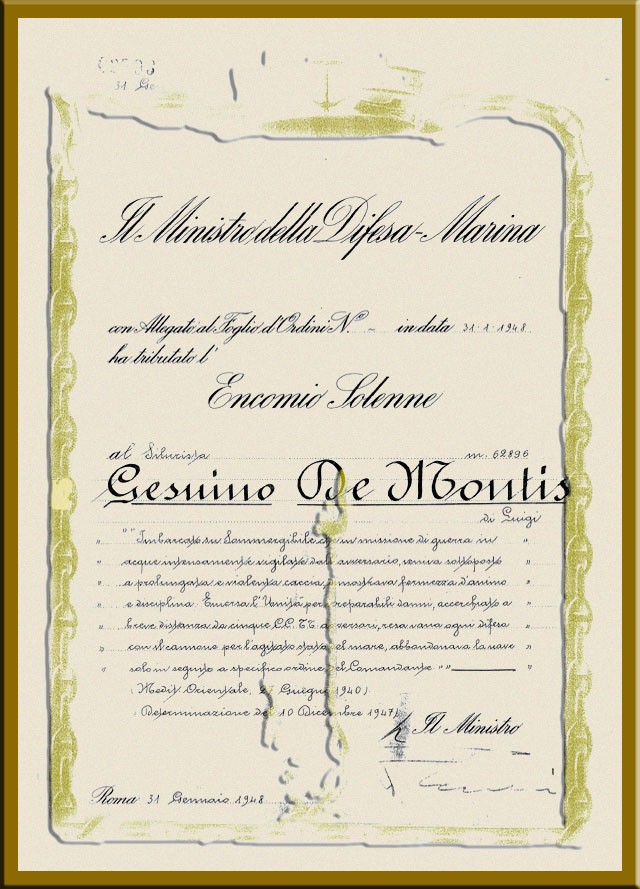

The official Commendation awarded to the torpedoman Gesuino De Montis

I thank God for saving me: 9 (TN they were actually 11) of my comrades died and I am now the only survivor still alive and, at 92 years old, I can say that I am still in good health.”