The submarine Ciro Menotti was a medium-cruising submarine of the Bandiera class (displacement of 933 or 942 tons on the surface and 1,096 or 1,147 submerged).

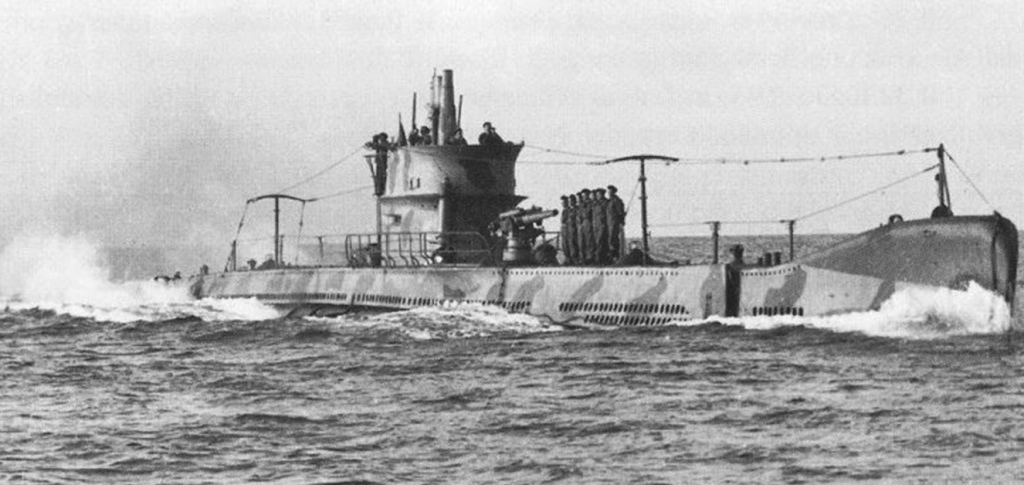

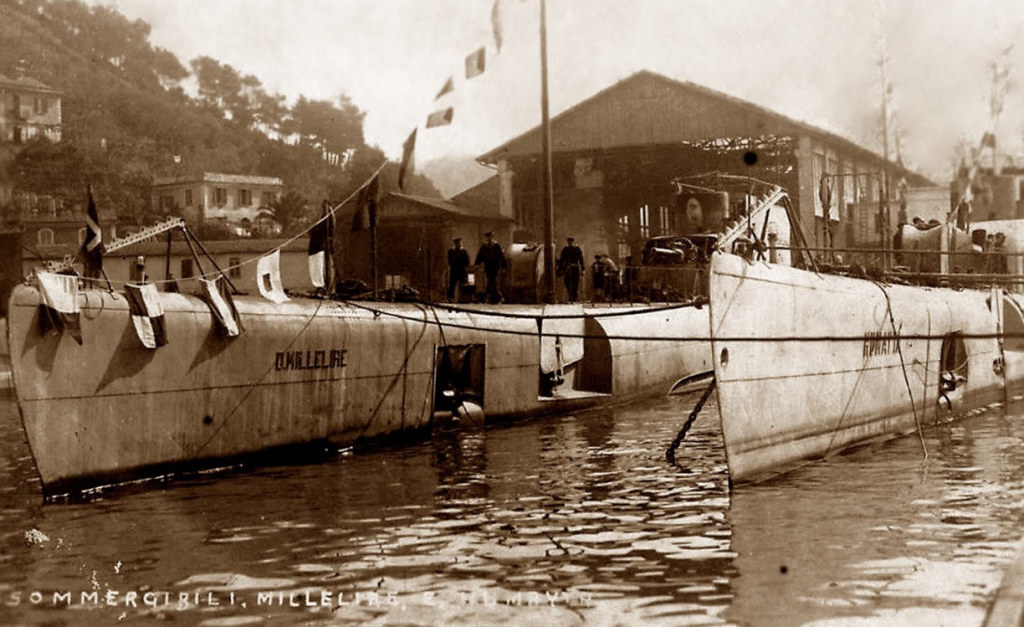

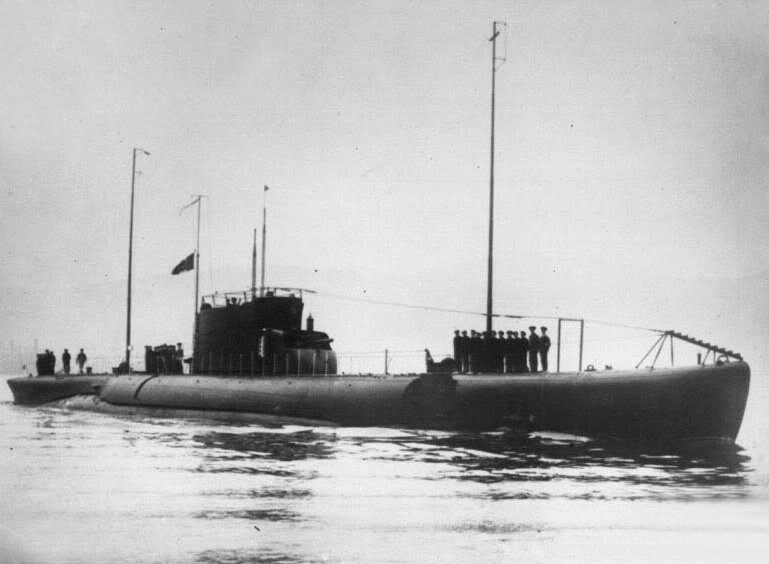

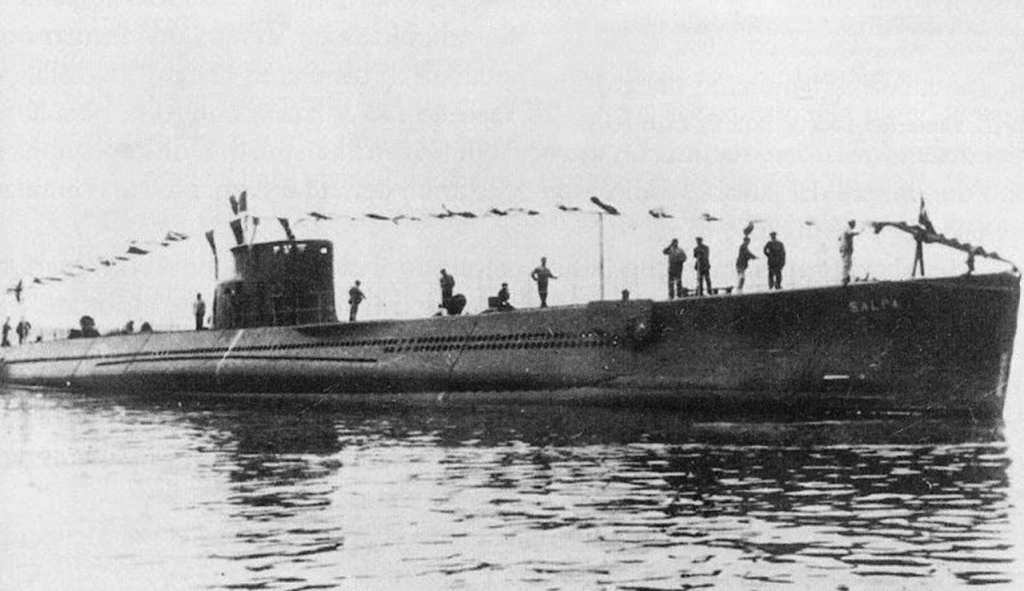

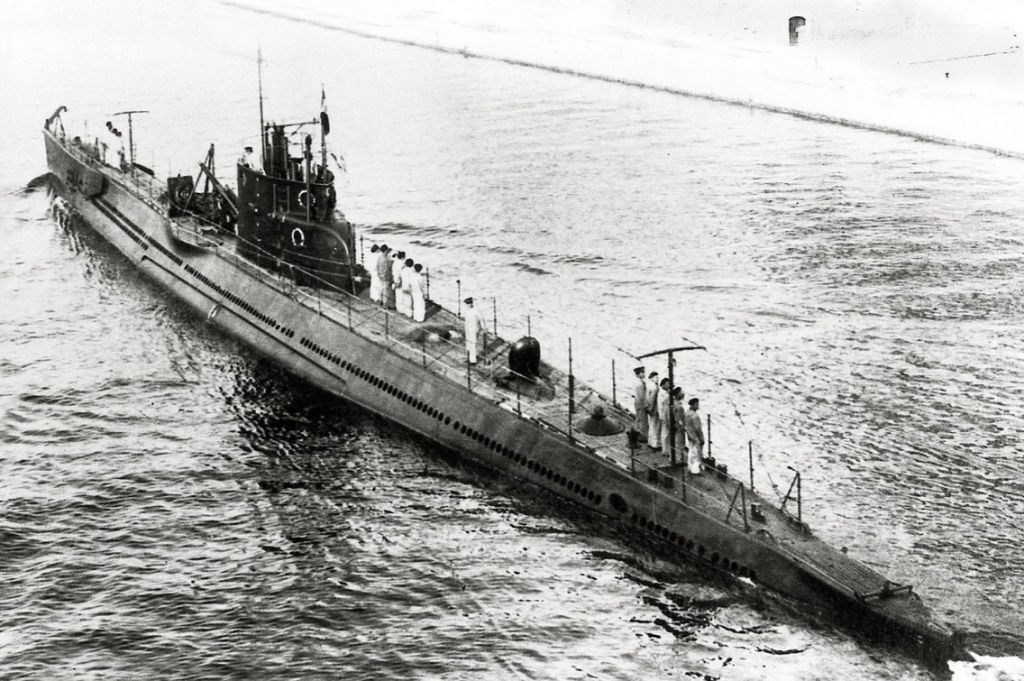

Menotti in the original and unusual configuration

(Collection Aldo Cavallini)

During the war, it carried out 36 missions, of which 23 were was patrols (mostly in the Eastern Mediterranean), 8 transport missions (during which it transported a total of 374.3 tons of supplies, of which 99.1 tons of gasoline cans, 194.3 tons of ammunition, 65.3 tons of food and 15.6 tons of miscellaneous material) and 5 transfer cruises, covering a total of 22,281 miles on the surface and 2,800 miles submerged (spending 180 days at sea), as well as 53 training sorties for the Submarine School in Pula.

The boat’s motto was “In virtute vis” (strength in virtue).

Brief and Partial Chronology

May 12th, 1928

Construction started at the Odero Terni Orlando shipyard in La Spezia (construction number 214). Another source gives the date as February 11th, 1928.

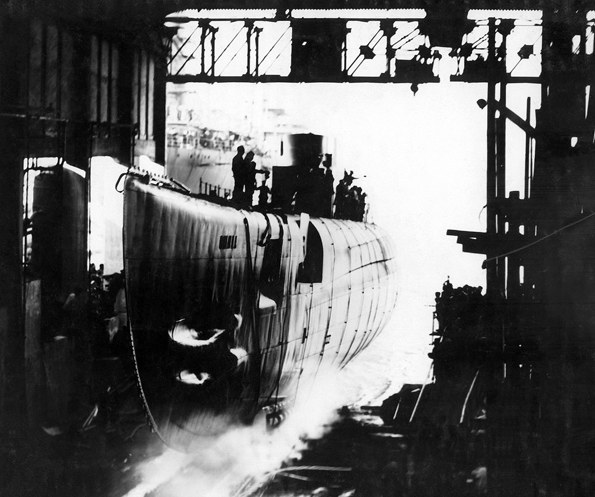

December 29th, 1929

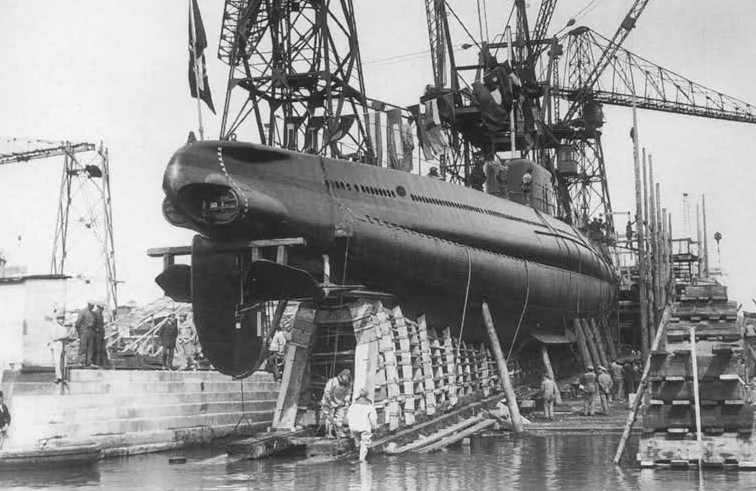

Menotti was launched at the Odero Terni Orlando shipyard in La Spezia. Other sources indicate the date of the launch as July 29th, 1929, or August 7th, 1929.

August 20th, 1930

During the trials, Menotti exceeded (its) the depth of 100 meters, descending to 102.5 meters.

A document signed by the crew of the Menotti certifying having reached a depth of 102.5 meters. The date is expressed using the Fascist calendar with the first year starting in 1922.

August 29th, 1930

Entry into active service. Other sources indicate the date of entry into active service as July 29th, 1930, or September 10th, 1930.

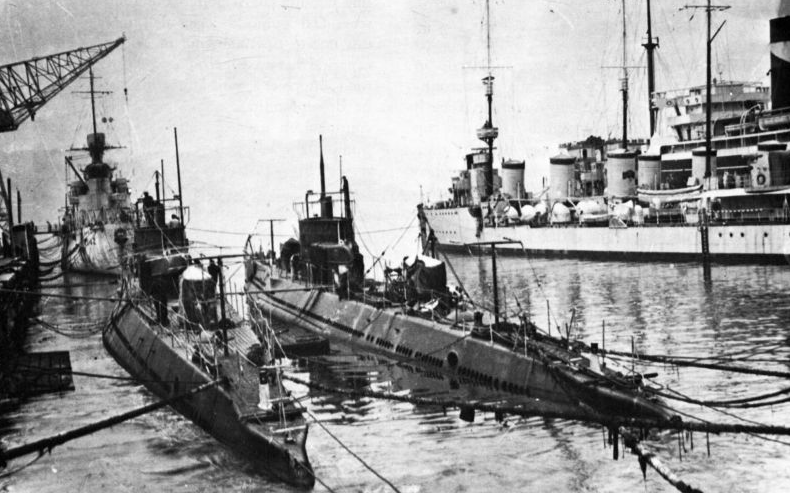

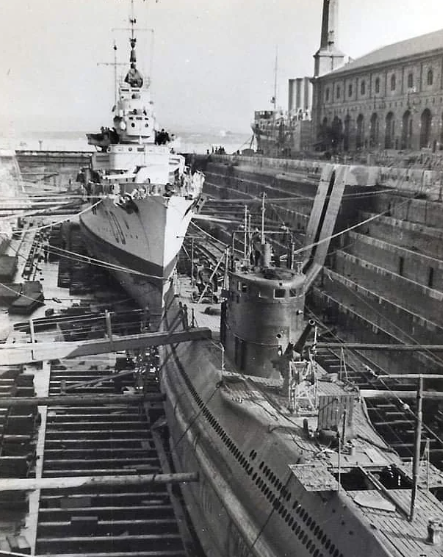

Menotti with the boat of the same class Santarosa while being fitted just before entering active service.

1930-1931

Shortly after completion, having shown an excessive slowness in the diving phase, Menotti and the other submarines of the Bandiera class underwent the removal of the periscope jackets, and two series of circular holes were drilled on the outer hull to shorten the diving time.

A few months later, as a tendency to pitch, poor transverse stability, and a tendency to dip by the bow during surface navigation (especially in the case of rough bow seas and/or high-speed navigation) also emerged. Thus, Menotti and twins were subjected to another round of modification works. At the bow the hull structures would be raised to insert a self-flooding box to mitigate pitching, thus creating a “big nose”; Side counter-fairings were installed (to increase stability) and the shape of the conning tower was modified, making it more enclosed. This improved the seaworthiness of the submarines of the class, but at the expense of speed (originally 17.9 knots on the surface and 9 knots submerged, which decreased to 15 knots on the surface and 8 knots submerged), drops caused by s the resistance generated by the new external counter hulls.

1931

Once the modifications were completed, the Menotti, together with the twin boats Fratelli Bandiera, Luciano Manara and Santorre Santarosa (and for a period, also the minelayer submarine Filippo Corridoni), went on to form the VI Submarine Squadron of Medium Cruise, based in Taranto.

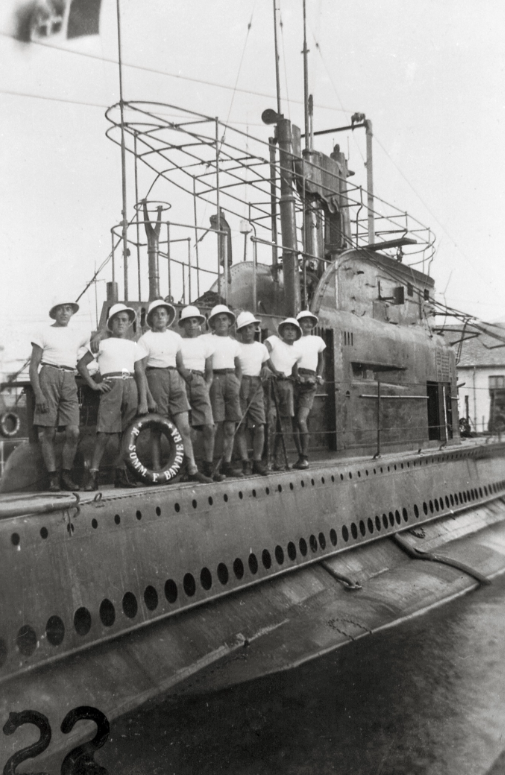

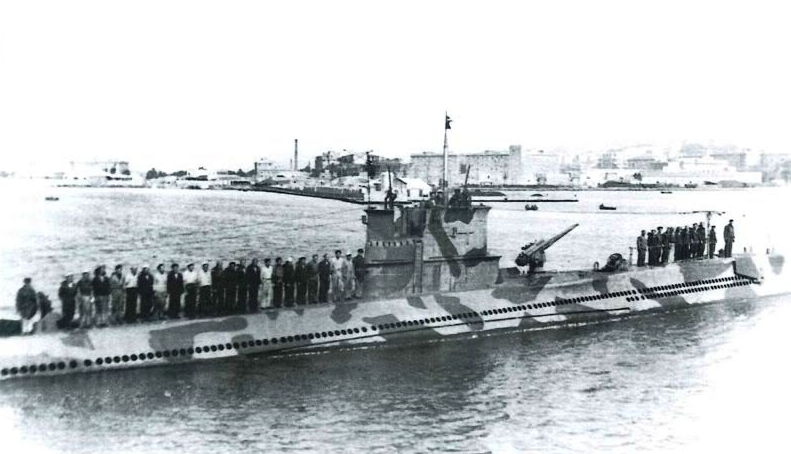

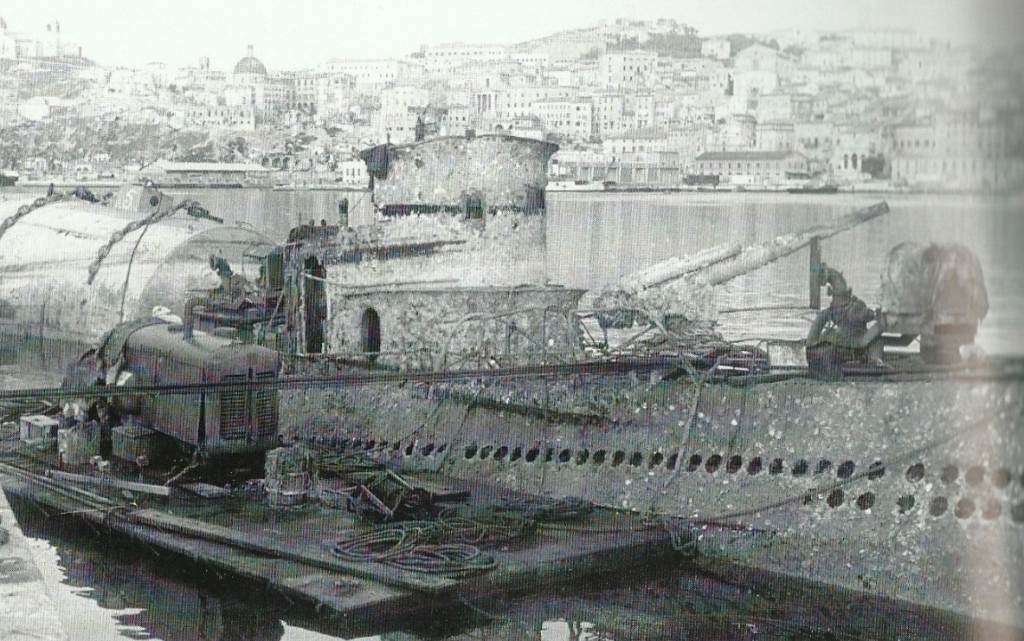

Menotti in Taranto after the various modifications were completed

In the same year, Menotti, Manara and Santarosa made a cruise to Tripoli and the Dodecanese, with the aim of verifying the performance of the class. There was still a tendency to dip in with the bow at sea.

May 30th, 1931

In La Spezia, Manara received the combat flag, donated by Modena, the birthplace of Ciro Menotti. Godmother of the banner was Donna Elena San Donnino.

1932

The VI Medium Cruise Submarine Squadron changes its name to VII Squadriglia.

1933

The VII Submarine Squadron was transferred to Brindisi. During this period (1932-1933) Menotti and the boats of the same class carried out, in addition to training, short cruises in Italian waters.

1934

The VII Squadriglia changed its name again to VI Squadriglia and was transferred to Naples. Menotti and Santarosa completed a cruise to the Balearic Islands and ports in Spain.

1935

Towards the end of the year, the squadron was transferred to Tobruk, where it remained for about a year.

1936

The command of Menotti was assumed by the Lieutenant Commander Vittorio Moccagatta, who had been previously embarked with the rank of lieutenant. During the same period (1936-1937) Lieutenant Giuliano Prini, future Gold Medal for Military Valour, served on the Menotti. At the time, the submarine was stationed in Tobruk, as part of the V Submarine Group.

January 22nd or 23rd, 1937

Menotti (Lieutenant Commander Vittorio Moccagatta) left Cagliari for a clandestine mission in the waters of Malaga, in support of Franco’s forces during the Spanish Civil War.

Between the end of January and the beginning of February 1937, seventeen Italian submarines were deployed in ambush in the waters between Almeria and Barcelona, including Menotti. Their task was to undermine the Spanish ports in the hands of the Republican faction and cut off the flow of supplies to them.

January 31st, 1937

Lurking at night off the coast of Malaga, after several hours of rough seas and eight days spent without having sighted anything, Menotti sighted the silhouette of a steamer at anchor, with the lights off, near the unlit lighthouse of Torrox (according to another source, on board it was believed that the ship was sailing, not at anchor). Commander Moccagatta decides to attack it and he launches two torpedoes, almost blindly, and manages to hit the ship with one of them, causing it to sink in shallow water (five meters of water: the ship remains partially emergent, and heeling on its side), a short distance from the shore (depending on the sources, between 60 and 300 meters from the beach).

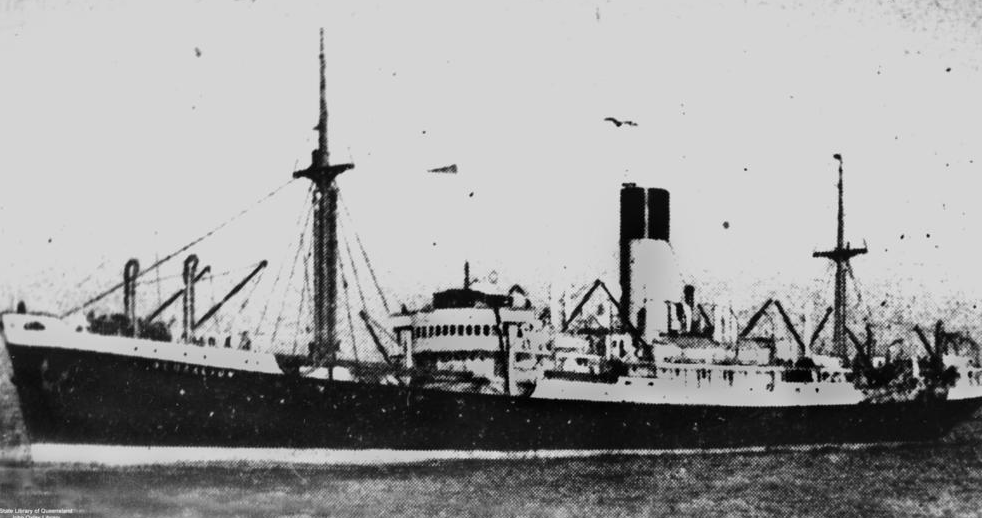

It was the steamship Delfin (1,253 GRT), at the service of Republican Spain and used for traffic between Alicante and Malaga with intermediate stops in Almeria and Cartagena (transporting mail and little else: a total of 2,900 tons of goods in 18 voyages between August 1936 and January 1937), under the command of Captain Fernando Gomila. Having left Barcelona a few days earlier with a cargo of flour, wheat, wine, oil and cod (another source also speaks of other goods, including razors and brown paper) destined for the population and garrison of Malaga, it had stopped at Alicante (January 28th), Almeria and finally at Motril, where it had spent the night between January29th and 30th, setting sail at 09:00 AM of the 30th for Malaga. At dawn, while proceeding inshore off Nerja, it was sighted by a Heinkel He 59 seaplane of the Aufklärungsgruppe See 88 of the German “Condor Legion” and subsequently attacked by another Heinkel He 59 (Lieutenant Werner Klumpfer), escorted by two Heinkel He 60s, which took off from Atalayon (Melilla) after the signal of the reconnaissance. The He 59 had dropped a torpedo on it, which, however, had missed it because it was defective (at first it had not even unhooked, while on the second attempt, carried out manually, it had unhooked, but had begun to turn in circles).

Manoeuvring to evade the attack, the Delfin had turned its bow towards the land and had voluntarily run aground at La Herredura (near Torrox) (according to a source, obeying superior orders previously given for such an eventuality, in order to make it possible to recover the cargo), after which it had been abandoned by the crew (who had reached the nearby coast in the lifeboats), even though they were not damaged. After the German planes had moved away, the crew returned on board and attempted to disentangle the ship, but at 4:30 PM on January 30th, a new air attack with bomb drops and strafing occurred. Again, the Delfin had not been hit, but the crew had again abandoned ship, refusing to return on board. The authorities in Malaga (the heads of the seafarers’ union, the delegations of the Republican Navy and the Transmediterranea company, the commander of the floating dock) had acted and it was thought to have it unlodged with the intervention of a fishing boat and the coast guard Xauen, but the latter was immobilized in port due to the damage suffered in a previous air attack.

The following night Menotti had sighted the steamship intact but deserted – not at anchor, as Moccagatta had mistakenly believed in the darkness, but stranded – and had hit it with a torpedo, causing it to sink and causing such damage that it was considered lost and irretrievable. The cargo, on the other hand, could be partially recovered, thanks to the shallow waters that had prevented the ship from remaining completely submerged (this according to some Italian sources, including the book “Men on the bottom” by Giorgio Giorgerini: however, an article by Francisco González-Ruiz published in the Spanish “Revista General de Marina” of January-February 1998 stated instead that the Spanish shore personnel, in announcing that after the torpedoing the Delfin was to be considered as completely lost – pérdita total del buque – he reported that “the cargo that can be recovered will be insignificant“). On February 2nd, the wreck was bombed again by other German seaplanes of the Aufklärungsgruppe See 88, including again the Heinkel He 59 of Werner Klumpfer, who believed he had hit it amidships with a 250 kg bomb dropped from a thousand meters high (so much so that he was awarded by Hermann Göring, head of the Luftwaffe, with a “diploma” that recognized him as the sinker of the Delfin, although it was already, at that point, a half-sunken wreck).

There were no casualties among the crew, as there was no one on board at the time of the torpedoing.

The sinking of the Delfin gave rise to a saying widespread in certain areas of Spain: “to be more lost than the rice ship”. The population of Malaga, besieged by the Phalangist forces and reduced to starvation, had in fact been informed of the expected arrival from Valencia of a ship loaded with provisions (rice, according to some versions, while according to another article “the rice ship” was the term generically used in those times to speak of a ship that transported food for the besieged populations): namely the Delfin. A ship that, anxiously awaited by the Malaga people, who went to the port for days hoping to see it arrive, never arrived. Hence the saying “to be more lost than the rice ship”, the Delfin, long-awaited and never arrived because it sank a few miles from its destination. According to one article, the nearby beach of Calaceite also owes its name to the sinking of the Delfin, having been invaded by a flood of fuel leaking from the sunken ship (“aceite”, in Spanish, means oil: “Calaceite” is the “beach of oil”). However, the fact that an article of the time (February 2nd, 1937) in the newspaper “El Luchador” mentions the site of the attack as “Punta del Aceite”, leads to doubt of this statement. The wreck of the Delfin is now a popular attraction for divers.

In the days that followed, Menotti continued its patrol of the coast of Malaga, without sighting any ships, but detecting intense vehicle traffic on the coastal road.

February 2nd, 1937

During the night (according to another source, at 05:00 PM), Menotti carried out a coastal bombardment action with its cannon, firing twenty-seven 102 mm grenades in ten minutes against the bridge and the coastal road of La Herradura (near Malaga), in support of the offensive unleashed by the Italian and Spanish nationalist forces for the conquest of Malaga.

On the Italian side, since it was not possible to discover too much for political reasons (officially Italy did not participate in the Spanish conflict), these actions could only be carried out secretly, at night, by submarines: among them the Menotti, sent to lie in wait on the access route to the port and charged with carrying out two coastal bombardment actions.

February 3rd, 1937

Also at night, Menotti again carried out a coastal bombardment of road targets in support of the operations against Malaga, firing another thirty-five 102 mm grenades against the Cala Honda (or Calanda, or Calahonda) viaduct in fifteen minutes. Málaga fell on February 8th.

February 9th, 1937

Menotti concludes the mission by reaching Naples (according to another source, Tobruk). For this mission, Commander Moccagatta was decorated with the Silver Medal for Military Valour, with the motivation “Commander of the submarine Menotti, during a war mission on the Spanish coast carried out in particularly adverse weather conditions, he gave proof of unwavering tenacity and strong offensive spirit by carrying out, despite considerable difficulties, two bombings of the port of Malaga, and resolutely attacking and sinking a smuggler in the vicinity of the enemy’s coast.”

August 5th, 1937

Menotti (Lieutenant Francesco De Rosa) set sail from Messina, where it was transferred to the III Grupsom, for a mission in the Strait of Sicily to counter the traffic of supplies to the ports of Republican Spain. More precisely, it patroledl the waters north of Pantelleria, in an area between Cape Lilybaeum in Sicily and Cape Bon in Tunisia.

August 18th or 19th, 1937

Menotti concludes the mission by returning to base. During the mission, it conducted four attack maneuvers, which it always interrupted at the last moment due to the impossibility of identifying the targets with certainty.

1937

Menotti, Manara, Bandiera and Santarosa formed the XXXII Submarine Squadron (later XXXIV Submarine Squadron) based in Messina.

May 5th, 1938

Under the command of Lieutenant Alberto Avogadro di Cerrione, Menotti took part in the naval magazine “H” organized in the Gulf of Naples for Adolf Hitler’s visit to Italy.

1939

Serving on the Ciro Menotti, framed in the XXXIV Submarine Squadron of Messina, was Lieutenant Carlo Fecia di Cossato, future ace of the Atlantic.

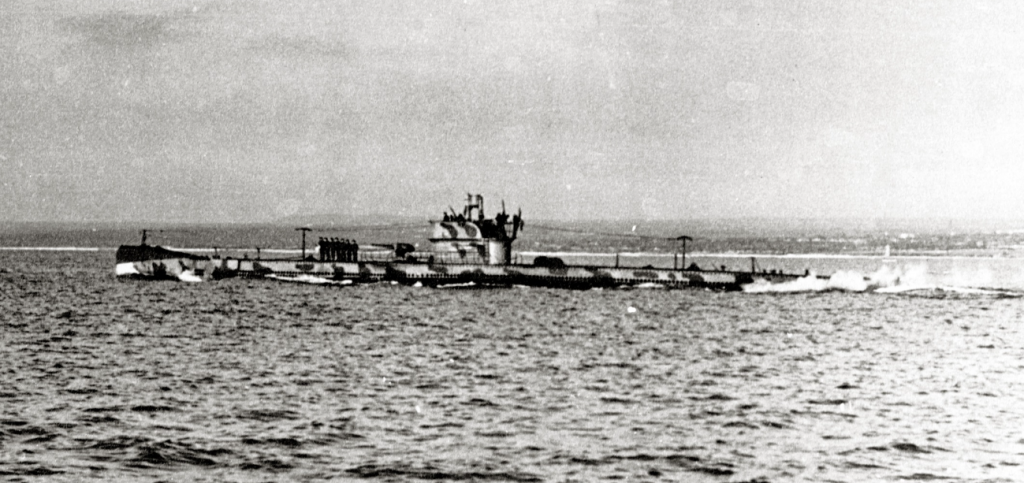

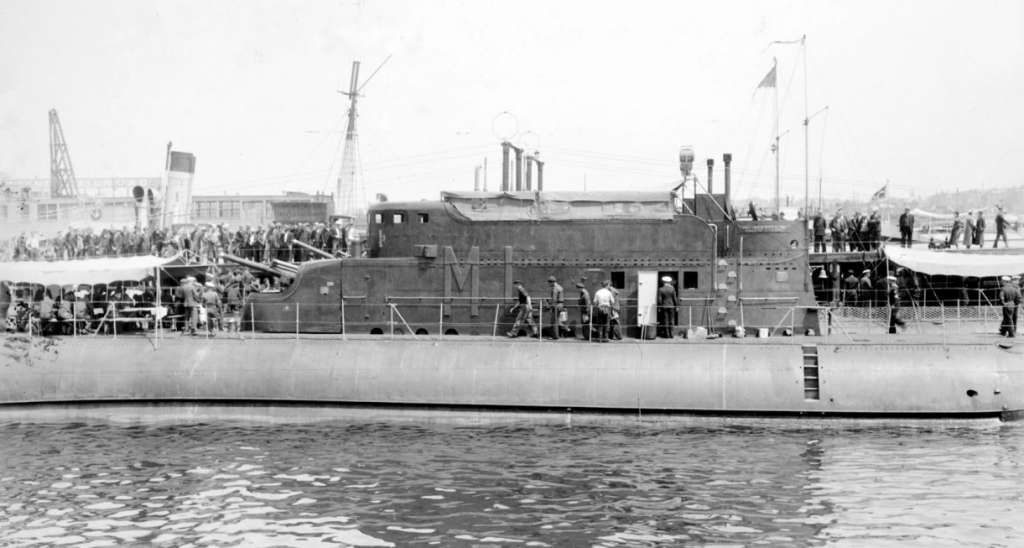

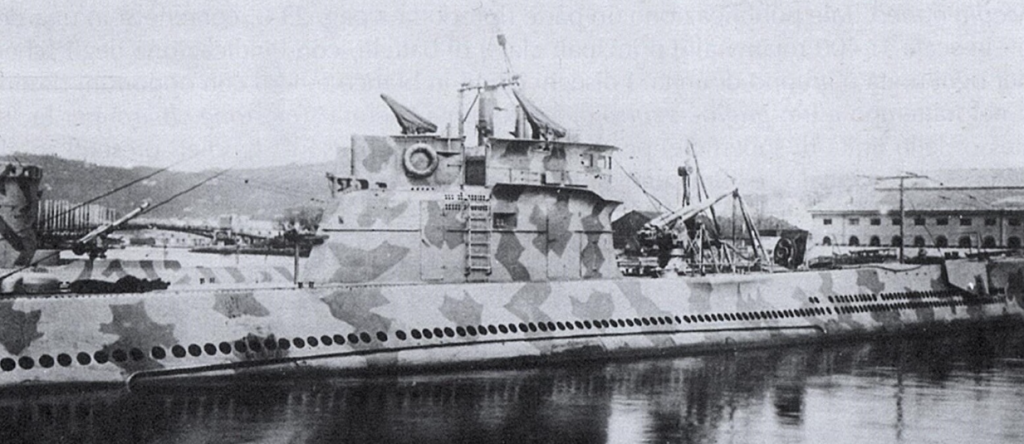

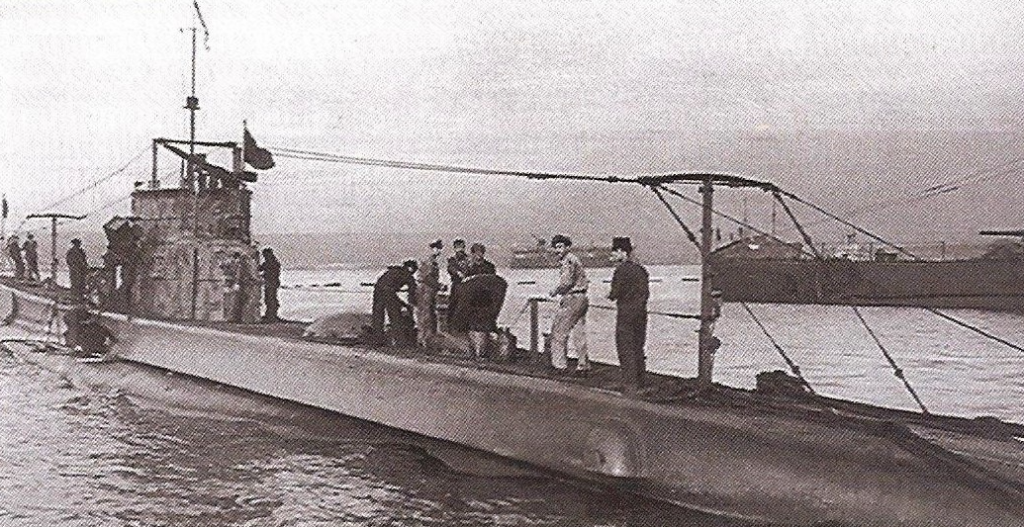

Menotti just before the beginning of the conflict

June 10th, 1940

Upon Italy’s entry into the World War II, Menotti (Lieutenant Carlo Fecia di Cossato) was part of the XXXIII Submarine Squadron of the VIII Grupsom, together with the boats of the same class Fratelli Bandiera, Luciano Manara and Santorre Santarosa, based in Trapani (another source states that it was part of the XXXIV Squadron of the III Grupsom of Messina, but it seems likely that this is a mistake).

June 19th or 21st, 1940

Menotti (Lieutenant Carlo Fecia di Cossato) left for the first mission of the war, an offensive patrol between Gaudo (islet south of Crete) and Ras el Tin (Libya).

June 27th, 1940

Menotti completed the first war mission, without having sighted any enemy ships. According to a source of uncertain reliability, during this mission Menotti was attacked by a Short Sunderland seaplane, which it repelled and damaged with the fire of its machine guns.

July 7th, 1940

The boat was sent on patrol south of Sardinia, together with the submarines Ascianghi, Axum, Glauco, Turchese, and Luciano Manara.

July 9th, 1940

Menotti was sent, together with five other submarines (Ascianghi, Axum, Turchese, Glauco, and Luciano Manara), between the meridian of Capo Spartivento Sardo and the junctions of Capo Carbonara-Capo Lilibeo and Capo Passero-Zuara, to patrol the waters between the island of La Galite and Tunis up to a distance of 50 miles from the Tunisian coast. The formation of this barrage was ordered by Maricosom (the Submarine Squadron Command, Admiral Mario Falangola) by order of the Chief of Staff of the Navy, Admiral Domenico Cavagnari, following the departure from Gibraltar of the British Force H. However, Menotti did not come into contact with the British forces, and the insuing attack on Cagliari did not produce any damage.

Summer 1940

During the summer of 1940 the Menotti, under the command of Carlo Fecia di Cossato, carried out various patrols in the central Mediterranean, without achieving any results. In the autumn of 1940 Fecia di Cossato was transferred to the Atlantic as second in command of the submarine Enrico Tazzoli, of which he would later take command.

November 11th-12th, 1940

Menotti was located in Taranto, moored in Mar Piccolo at the submarine quay (together with Ambra, Anfitrite, Atropo, Malachite, Pietro Micca, Naiade, Sirena, Ondina, Uarsciek and Zoea of the IV Grupsom, Dagabur, Serpente and Smeraldo of the X Grupsom and Giovanni Da Procida of the III Grupsom; Menotti is the only boat of the VIII Grupsom present in the port) when the naval base was attacked by British torpedo bombers taking off from the aircraft carrier Illustrious, which torpedoed three battleships (Conte di Cavour, Littorio and Duilio, sinking the first and seriously damaging the other two) in what would become known as the “night of Taranto”.

October 28th, 1940

Menotti, together with Luigi Settembrini, Tricheco, and Dessiè, was among the submarines sent to form a barrage south of Crete, between the Ionian Sea and the Aegean Sea.

October 31st, 1940

The British Mediterranean Fleet, which had sailed from Alexandria in Egypt in the early hours of October 29th following the Italian attack on Greece and had entered the Ionian Sea. In the early hours of the 31st it had reached as far as Zakynthos, Kefalonia and Corfu. However, it was not sighted either by Menotti or by the other submarines of the barrage, whose meshes were too wide. The British fleet return to Alexandria on November 2nd.

January 10th through 20yh, 1941

Menotti was on patrol off the Otranto Channel to protect the traffic of supplies to Albania.

End of January 1941

Menotti formed a barrage in the Lower Adriatic and northern Ionian Sea together with the submarines Ambra, Turchese, Tito Speri, Filippo Corridoni, Domenico Millelire, Jalea, and Dessiè.

February 22nd through – March 7th, 1941

Another patrol near the Otranto Channel to protect convoys to Albania.

March 1941, the submarine Ciro Menotti (background) and the submarine Giovanni Da Procida (foreground) moored in Taranto alongside GM 64 Buttafuoco “pontoon” (former Austro-Hungarian armored frigate Erzherzog Albrecht, built in 1870-1874, decommissioned in 1908, and Italian war booty after the World War I), used as a barracks for the crews of the submarines of the Grupsom inTaranto.

April 9th through 21st, 1941

Third patrol in the area of the Otranto Channel to protect traffic with Albania.

May 1941

The command of Menotti was taken over by the Lieutenant Commander Ugo Gelli.

May 18th, 1941

Menotti (Lieutenant Commander Ugo Gelli) set sail from Taranto to lie in ambush south of Zakynthos, following the report of the sighting in those waters of a British submarine which, it was feared, could attack the ships that are gathering in the Gulf of Patras in preparation for the German invasion of Crete (operation “Merkur”) as well as to transfer German troops and armored vehicles to Italy that were to be sent from there to the eastern front .

May 20th, 1941

Shortly before midnight, Menotti sighted a dark silhouette sailing eastward at about 15 knots. It was probably the British minelayer H.M.A. Abdiel, which a few hours later would lay a minefield off Cape Dukato (Santa Maura Island, in the Ionian Islands). The destroyer Carlo Mirabello, the gunboat Pellegrino Matteucci, and the German steamers Marburg and Kybfels sank on these mines.

Summer 1941

Subjected to a period of maintenance at the Arsenal of Taranto.

December 1941

Starting from this month, Menotti, by now in mediocre conditions of efficiency and considered inadequate for offensive roles (according to one source, already in 1940 Menotti had reduced war value), was assigned to the task of transporting supplies on the routes to Libya (other sources state that it was assigned to this use starting from May 1942, but this is an obvious error).

December 1st, 1941

Menotti (Lieutenant Commander Celli) left Taranto at 01:00 PM carrying a cargo of 25 tons of food (another version speaks of 14 tons, more precisely of crackers) destined for the Bardia stronghold.

For some time now, the Army Commands in Libya, especially the German ones, have been pressuring the Navy to use submarines to transport supplies to small ports, such as Derna and Bardia, closer to the front line and where merchant ships could not dock. Supermarina opposed it, given the scarce amount of supplies that could be embarked on a submarine (in the best of cases, a tenth of what a modest merchant ship could carry), but in the end it gave in to constant pressure.

At first, the large ocean-going submarines of the Admiral-class and minelaying submarines, which had an above-average load capacity, were destined for this service, but in December, as a result of the increasingly pressing German requests (the situation was particularly difficult: in November the losses in supplies sent by sea were very high, almost 70%, and the British unleashed a large-scale offensive called “Crusader”), Supermarina further intensified the traffic by submarines, also assigning elderly boats such as Menotti which, If on the one hand they did not have great war value (which means that it was not a great loss to divert them from normal operational use), on the other hand they had an even smaller load capacity.

December 4th, 1941

Menotti arrived in Bardia at 05:00 PM, unloaded the supplies and left at 08:30 PM. to return to Taranto, carrying fourteen officers POW.

The arrival of the crackers was not very welcome by the garrison of Bardia, which already had too many and would prefer other types of supplies, of which there was a shortage: to satisfy at least a small part of this request, the crew of Menotti gave to the men of the garrison, by order of Commander Celli, all the (modest) supplies of eggs and vegetables of their rations.

In the report drawn up at the end of the mission, Commander Celli wrote that “The Italian general of Bardia [presumably Major General Fedele De Giorgis, commander of the 55th Infantry Division “Savona” whose men formed three-quarters of the garrison of Bardia] has pointed out that, according to requests already made, he has an urgent need for fuel oil and artillery rounds, It also expresses the desire (shared by the German command) that, instead of crackers, of which there is already ample availability on the spot, food of other kinds should be sent, and possibly legumes ...’

December 8th, 1941

Menotti arrived in Taranto at 11.30 AM.

December 14th, 1941

Menotti set sail from Taranto at 03.40 AM for a new transport mission, this time to Benghazi, loaded with 45 tons of fuel, 8.5 tons of food, 5.5 tons of spare parts for vehicles and 7.5 tons of ammunition (a total of 66.5 or 67,7 tons of supplies, depending on the source).

December 15th, 1941

At 07:00 AM, the British submarine P 34 (later Ultimatum, Lieutenant Peter Robert Helfrich Harrison), sailing eastwards, sighted a “U-boat” sailing on the surface about 110 miles west of Zakynthos, dived and approached to intercept it, but lost sight of it. The “U-boat” was in all probability the Menotti, sailing towards Benghazi.

December 16,th 1941

Menotti reached Benghazi at 02.30 PM., disembarked the cargo, and left for Taranto at 06:45 PM, with fifteen POW and some repatriating soldiers on board.

December 20th, 1941

The boat arrived in Taranto at 02.10 PM.

January 13th, 1942

Menotti left Taranto for Tripoli at 01.40 PM, carrying 20 tons of weapons and ammunition, 15 tons of supplies, 1.5 tons of various materials and 0.3 tons of gasoline in jerrycans.

January 14th, 1942

The boat arrived in Augusta at 06:00 PM and stayed there for almost twenty-four hours.

January 15th, 1942

Menotti left Augusta at 05:00 PM bound for Tripoli.

January 18th, 1942

The boat arrived in Tripoli at 02:00 PM.

January 19th, 1942

Once the supplies were unloaded, Menotti left Tripoli at 03:00 PM. bound for Augusta.

January 21st, 1942

At 07:00 AM, in position 36°55′ N and 15°38′ E (25 miles southeast of Augusta), the British submarine H.M.S. Unique (Lieutenant Anthony Foster Collett), while submerged at a depth of 21 meters, detected engine noise on a bearing 110°, moving to the left. Immediately moving to periscope depth, Collett did not see anything. Since the detection of the source of the noise changes rapidly, it was believed to be a destroyer or a torpedo boat, but after a few minutes the noise disappears. At 07:16 AM. H.M.S. Unique again detected noise on a 160° bearing, moving to the right at low speed, and at 07:20 AM it sighted a small dark object on this bearing, identified at 07:24 AM as a submarine. It the Ciro Menotti (Lieutenant Commander Ugo Gelli), who was returning from Tripoli to Augusta at the end of his transport mission.

Since 07.20 AM. H.M.S. Unique had brought all the torpedo tubes in “ready to be fired” state towards the unknown unit, and at 07.24 AM Collett decides to attack, but he was unable to immediately get into a favorable position. At 07.30 AM, the attack periscope stopped working, forcing the use of the other periscope, and only at 07.37 AM did the British submarine manage to launch four torpedoes against Menotti.

No one hit, and the Italian submarine, which did not even notice the attack, continued its course, disappearing from sight at 07.48 AM. It reached Augusta unscathed at 10.30 AM (According to another source, however, H.M.S. Unique attacked not Menotti but the Ruggero Settimo, which preceded it on the same route).

February 10th through 13th, 1942

Sent off the coast of Cyrenaica to counter the navigation from Alexandria to Malta of a British convoy as part of the “MF 5” operation which included convoy MW. 9. To attack the British convoy bound for Malta, eleven Italian submarines were deployed in an area of just over 800 square miles: in addition to the Menotti, also Topazio, Trirus, Sirena, Dandolo, Malachite, Ondina, Perla, and Platino.

Menotti did not encounter “MW. 9”, which was destroyed by the Luftwaffe. This was the last of 23 war patrols carried out by Menotti in the Eastern Mediterranean since the beginning of the war, all without results.

1942

The 102/35 mm gun was removed and replaced with a longer and more modern OTO Mod. 38 of 100/47 mm, with better range and shorter loading times (modification made on Menotti alone, among the submarines of its class). The conning tower was also resized.

March 7th, 1942

Menotti was assigned to the Submarine School in Pula to be used in training (according to other sources, it was assigned there from March 7th, 1943 (TN clearly a mistake)).

March-November 1942

Menotti carried out 53 training sorties for the Submarine School, as well as some protective anti-submarine patrols in the Upper Adriatic.

August 1942

In the second half of the month, Menotti carried out a protective patrol in metropolitan waters (presumably in the Adriatic).

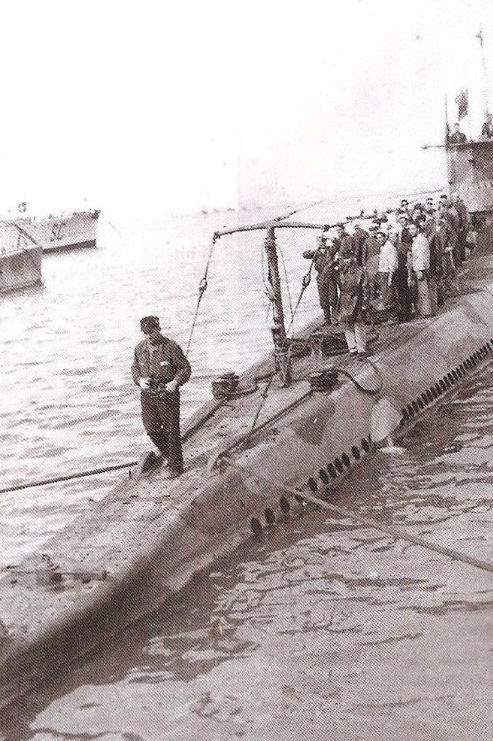

The Menotti on patrol or during a training sortie from Pola

May 13th, 1942

According to a source, on this date Menotti departed from Augusta to carry out a transport mission to Tripoli, with a cargo of 18.2 tons of weapons and ammunition. There is, however, no trace of this mission in the chronology contained in the appendix to the USMM volume “La difesa del traffico con l’Africa Settentrionale dal 1° ottobre 1941 al 30 settembre 1942” (The defense of traffic with North Africa from October 1st, 1941, to September 30th, 1942). Moreover, the source that mentioned this mission also stated that it was Menotti’s first transport mission, which is wrong (the first was the one that began on December 1st, 1941).

November 1942

At the end of the training activity for the Submarine School of Pula, Menotti was again deployed to Augusta to resume its activity as a transport submarine.

November 18th, 1942

Menotti departed Taranto for Tripoli at 11.50 PM, carrying 30 tons of ammunition and 21 tons of gasoline in cans.

November 23rd, 1942

Menotti stopped in Buerat during the night between the 22nd and 23rd, then continued to Tripoli, where it arrived at 01:00 PM. At 10:00 PM on the same day, having disembarked the cargo, it left Tripoli to return to Taranto.

November 26th, 1942

The boat arrived in Taranto at 3.30 PM.

December 12th, 1942

Menotti left Taranto for Tripoli at 3.15 PM, carrying 35 tons of ammunition, 21 tons of gasoline, 11 tons of motor and 1.5 tons of various materials.

December 16th, 1942

The boat arrives in Tripoli at 8.45 AM, disembarked the cargo and left again at 3.50 PM.

December 19th, 1942

Menotti arrived in Taranto at 02.20 pm.

January 1943

The boat carried out a mission of transporting materials and personnel (among the latter, the Lieutenant of Naval Weapons Sebastiano Caltabiano) from Trapani to Lampedusa.

April 1943

Another transport mission (ammunition and other supplies) with destination Lampedusa.

April 19th, 1943

Sailing in the Strait of Sicily, Menotti (Lieutenant Commander Ugo Gelli) was attacked by a four-engine aircraft, which it manages to shoot down with the fire of its machine guns. The second chief torpedoman Alberto Lombardo, a pointer of the machine gun, was decorated with the War Cross of Military Valor.

The sub-chief torpedoman Alberto Lombardo and commander Gelli at the machine gun that shot down the attacking plane

(Photo Renato Lombardo, nephew of Alberto Lombardo)

The sub-chief torpedo man Alberto Lombardo (Trapani, February 8th, 1915 – Australia, 1987). He joined the Navy in 1935, and after two years of training on the heavy cruiser Pola, he was assigned to Marina Trapani until 1940, when he was embarked on the Menotti, on which he served throughout the conflict. His combat post was in the forward torpedo room, with the task of communicating the commander’s orders to the torpedo operator. For his service in the war, he was awarded two War Crosses for Military Valor and a Cross of War Merit.

July 8yh, 1943

Lieutenant Giovanni Manunta took over command of the Menotti.

Lieutenant Giovanni Manunta aboard Menotti

July 27th, 1943

Menotti departed from Brindisi with two squads of sappers from the “G” Department of the “San Marco” Regiment on board, who were to attack the Allied airfields located near Benghazi destroying as many planes as possible (Operation “Beta”). In all, there were 19 or 20 saboteurs (depending on the sources), commanded by Sub-Lieutenant De Martino and Lieutenants Visintini, and Caselli.

August 4th, 1943

On the night between August 3rd and 4th, Menotti landed the 20 saboteurs on the Cyrenaica coast, near Benghazi. It was to remain in the area to retrieve them at the end of the mission, but this was prevented by the systematic hunt carried out against the boat by the enemy air force.

None of the saboteurs was to reach the pre-established point for re-embarkation: a group of ten raiders (an officer and nine men of the “San Marco”) was discovered and attacked by groups of armed Arabs between the coast and kilometer 10 of the Benghazi-Agedabia road. Barricaded in a building and besieged by attackers, they were finally captured by a British patrol of No. 4 AA Practice Camp in the late afternoon of August 4th. The second group of ten raiders, landed near Suani el-Terria (Sawānī Tīkah) and was also captured by a patrol of the Sudan Defence Force, which then handed them over to a platoon of Squadron C of the 8th (King’s Royal Irish) Hussars.

September 1943

Menotti was part of the IV Submarine Group, based in Taranto, together with Atropo, Marcantonio Bragadin, Filippo Corridoni, Giovanni Da Procida, Otaria, Luigi Settembrini, Ruggero Settimo, Tito Speri and Zoea.

September 3rd, 1943

Following the landing in Calabria of the British Eighth Army (operation “Baytown”), Maricosom activated the “Zeta” Plan, prepared since the previous March, which provided for the deployment of most of the surviving submarines to defend the coasts of Campania and Calabria against Anglo-American landing attempts. Among these boats there was Menotti, which left Brindisi at 06:00 PM and was deployed in the Gulf of Squillace (Ionian Sea). In addition to Menotti, between that gulf and the Strait of Messina (along the eastern coast of Calabria) there were Onice, Luigi Settembrini and Zoea, while Vortice and Luciano Manara were sent to the Ionian coast of Sicily, Brin and Alagi in the Gulf of Salerno, Diaspro and Marea in the Gulf of Policastro, and the pocket submarines CB 8, CB 9 and CB 10 between Capo Colonne and Punta Alice.

However, when it became clear that Operation “Baytown” was limited to the southern coast of Calabria and that no other landings were in progress, Maricosom returned all submarines to sea with the exception of Settembrini, Vortece, Onice and Zoea. According to Giuliano Manzari’s essay “Italian submarines from September 1943 to December 1945”, published in the Archive Bulletin of the Historical Office of the Navy in December 2011, Menotti remained at sea until the armistice.

According to the book “Uomini sul fondo” by Giorgio Giorgerini, Menotti remained at sea together with Vortece, Onice, Settembrini and Zoea, to which on September 7th – following the redeployment of part of the submarines of the “Zeta” Plan determined by the sighting of the signs of the “Avalanche” operation, the landing in Salerno – four other submarines (Fratelli Bandiera, Squalo, Jalea and Marcantonio Bragadin) were to complete the deployment in the Ionian Sea, between Sicily, Calabria and the Apulian end of Capo Santa Maria di Leuca. Eleven other submarines (Brin, Alagi, Diaspro, Giada, Galatea, Marea, Nichelio, Platino, Turchese, Topazio, and Velella) were simultaneously deployed in the Tyrrhenian Sea, between the Gulf of Paola and the Gulf of Gaeta.

Armistice

In the confusing days that followed the announcement of the armistice of Cassibile (September 8th,1943), Menotti was the protagonist of an episode that demonstrates the atmosphere of uncertainty, tension, and mistrust of that period. The proclamation of the armistice surprised the crew while they were patrolling the waters of the Ionian Sea, under the command of Lieutenant Giovanni Manunta. The skipper, uncertain of what to do and doubtful of the authenticity of the orders he was intercepting via radio, consulted on the morning of September 9th with his peer Pasquale Gigli, commander of the submarine Jalea, whom he met in the Ionian Sea. After the exchange of opinions, the paths of the two submarines diverged: Manunta decided to sail with Menotti to Syracuse, while Gigli decided to take his Jalea to Gallipoli.

In the late afternoon of that same day, while sailing in the Otranto Channel, Menotti was intercepted by the British submarine H.M.S. Unshaken (Lieutenant Jack Whitton), which was returning to Malta after its eighteenth war patrol, carried out off the coast of Brindisi.

H.M.S. Unshaken was on the surface when the sonar announced that he had detected noise from engines going at high speeds. Fearing that it might be an enemy submarine, Whitton ordered to dive, after which he sighted Menotti at the periscope at 06:25 PM, in position 39°51′ N and 19°04′ E, five miles away on 180° bearing. At first, however, the British commander had some difficulty in determining the newcomer’s nationality through the periscope. The hull was not visible, still beyond the horizon, while the conning tower was glistening in the sun. Identified at first as a German U-boat, Whitton maneuvered to attack, but at 06:50 PM he realized that the submarine sighted was Italian (H.M.S. Unshaken logbook reports: “1825 hours – In position 39°51’N, 19°04’E sighted a U-boat bearing 180°, range 5 nautical miles. Enemy course 340°. Closed to attack. 1850 hours – The submarine was now seen to be not German but Italian (H.M.S. Unshaken had received a signal to cease hostilities against Italy at 2231/8). Commander Whitton of the Unshaken would describe those moments years later: ” At about 1500 yards range, and with but a few minute to go before firing torpedoes, I had a long and careful look at the target: the submarine was Italian. She was also flying her ensign and had an unusually large number of chaps an her bridge, whom I could clearly see were gazing north-west and, no doubt, at their beloved country a few miles away. With that bunch on the bridge, she was hardly in a position to do quick dive….We would try to stop her, then board her. “

Once nationality was ascertained, H.M.S. Unshaken emerged (it was seven o’clock in the evening) and fired a warning shot with his cannon, ordering the Italian submarine to stop. Menotti, however, refused to obey, and responded to the cannon fire with a burst of machine gun fire (according to a British official source, Commander Manunta later justified the opening of fire by stating that he had initially mistaken the Unshaken for a German U-boat). H.M.S. Unshaken reacted by maneuvering to get into a position suitable for launching the torpedoes, and only at this point did the Italian boat cease fire and condescend to stop.

H.M.S. Unshaken then joined Menotti and approached as far as he could hear, at the same time sending on board the Italian unit a squad of three sailors, commanded by Lieutenant David “Shaver” Swanston, a great friend of Whitton as well as “supernumerary” commander at the 10th Submarine Flotilla of Malta, embarked on H.M.S. Unshaken for that mission. Whitton instructed Swanston to take control of Menotti. Whitton’s words: ” There were even more chaps on the bridge than before; I suppose they had come up to see what the hell was coming next. By this time Unshaken was alongside, stopped, with ourbows against the Italian’s bow. The boarding party, led by Shaven brandishing a 45 were juming across. They raced along the forward casing and climbed up the enemy’s conning tower. The objective: to secure the conning tower hatch and so stop him diving, then subdue any further resistance. “

Ward, who according to a British account was armed, without his knowledge, with an unloaded pistol, the bullets being contained in a separate envelope that was given to the sailor along with orders.

Once the two submarines were side by side, and the British squadron had boarded the Menotti, a lively discussion ensued between the Italian commander, who wanted to reach Brindisi, and the British commander, who demanded that Menotti set course for Malta. Whitton again: “… A somewhat heated exchange followed,’ Whitton writes,as the two COs, each on his own bridge, side by side, voiced their intentions: ‘Brindisi’, he shouted. ‘Malta’ I yelled. ‘Brindisi’….’Malta..”

British historian John Wingate, author of the book “The Fighting Tenth,” adds further details to the description of this surreal situation: the second-in-command of the Unshaken, Second Lieutenant Herbert Patrick “Percy” Westmacott, passed Whitton his officer’s cap, “to give a little more solemnity to the situation.” Finally, Whitton managed to “persuade” Manunta by having him explain the details of the armistice and, above all, by pointing H.M.S. Unshaken’s gun at Menotti conning tower.

The commander of H.M.S. Unshaken concludes his story as follows: “I put it on [my cap]. The 76 mm gun, still cocked, and ready for action, was ordered to load one HE [High Explosive] round. The servant, a sailor with considerable initiative, lifted the 76 mm high-explosive projectile: he showed it, as a magician would have done in the theater, to an Italian audience that was very impressed. Then he let the bullet slide into the gun, closing the breech dryly. The muzzle of the gun was aimed at the stomach of the Italian commander, at a distance of about thirteen feet [less than four meters]. Shaver, standing next to him, was asked to move aside. With a shrug of the shoulders and his hands in the air, the Italian agreed: Malta. We were singing the same song now, and I don’t think it was my cap that had that effect. With Shaver Swanston and the boarding crew at the checkpoint, the Italian boat, the Menotti, would set course for Malta.”

To make sure that Menotti reached Malta and did not attempt to dive and escape, Whitton had one of Menotti’s officers and three sailors transferred to H.M.S. Unshaken as “hostages”. He also decided to make the journey to Malta, which would have taken two days, remaining mostly on the surface, in order to better keep an eye on the Italian submarine.

The episode is reported in H.M.S. Unshaken’s logbook as follows: “7:00 PM – I emerge and fire a cannon shot astride the bow of the submarine [the Menotti] to stop it. The Italian submarine responds with a burst of machine gun fire. The Unshaken then alters its course as if to launch torpedoes, at which point the machine-gun fire ceases. I approach the Italian [submarine] until I reach the voice distance. The Italians therefore claim that they are on their way to Brindisi to receive orders there. We then tell them to reverse course and head for Malta, but they refuse, but when we point our cannon at them and Lieutenant Swanston explains the details of the surrender, the Italian commander changes his mind. At this point we learn that the submarine is the Ciro Menotti. He sent a boarding party of four men under the command of Lieutenant Swanston and took as hostages an officer and three Italian sailors. 8.00 PM – We proceed towards Malta with Menotti in front of us» (“1900 hours – Surfaced and fired one round across submarine’s bows to stop her. The Italian submarine answered with a burst of machine gun fire. Unshaken then altered course as to fire torpedoes, the machine gun fire then stopped. Closed the Italian to hailing distance. The Italians then stated they were making for Brindisi for orders. We then told him to turn round and make for Malta but they refused but when we pointed our gun towards him and when Lt. Swanston had explained the details of surrender the Italian Commanding Officer changed his mind. It was then found out that the submarine was the Ciro Menotti. 1900 hours – Sent over a boarding party of four with Lt. Swanston in command and took one Italian officer and three ratings as hostages. 2000 hours – Proceeded on passage to Malta with Menotti in front”).

On 10 September, Menotti and H.M.S. Unshaken, sailing towards Malta, sighted a German aircraft, but no attacks occurred. Every evening the Unshaken approached Menotti to check that the situation on the Italian unit was under control; according to Wingate, “Swanston complained of filth and lack of discipline, but evidently had no problem with the officers, who openly expressed their repugnance to the Germans in particular and to the war in general. The commander of Menotti later told Whitton that he had no orders to proceed to an Allied port, except for a message which he believed to be false, since the Allies had used captured Italian ciphers. He was troubled by the defeat; He hated the Germans but didn’t mind surrendering to the British.”

On September 11th, (according to British sources; Italian sources speak instead of September 12th, one even at 05.30 PMon the 14th) Menotti entered Malta escorted by H.M.S. Unshaken (a British source even defines it as “under arrest”, given the particular circumstances of its “detention”), passing among the other Italian warships that had preceded it there and which were now at anchor in the Grand Harbor. Wingate concludes the narrative of the episode as follows: “That afternoon the commander of H.M.S. Unshaken received what must have been one of the most unusual receipts ever compiled in history. Written on paper with an embossed crown from Lazaretto’s typewriter, it was addressed to Her Majesty’s submarine Unshaken and was dated Saturday, September 11th, 1943. Signed by George Phillips in his capacity as commander of the 10th Submarine Flotilla, it read: “Received by Lieutenant J. Whitton, R. N., one Italian submarine named Menotti and sixty-one crew.”

Menotti moored at Lazaretto Creek, near Marsa Muscetto, near the local British submarine base. It was the first Italian submarine to reach Malta after the armistice; the others did not begin to flow in until September 13th.

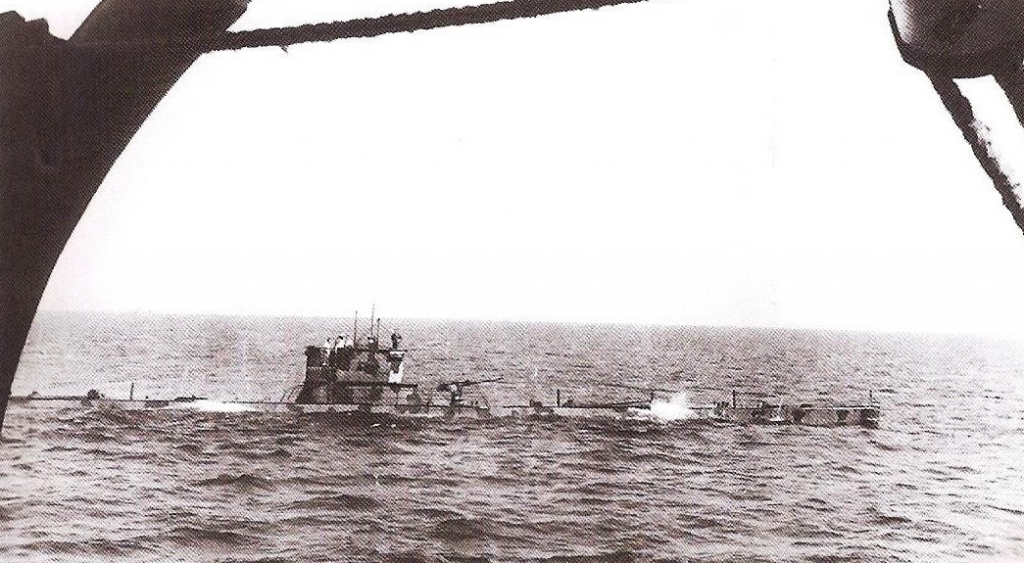

Menotti moored at Lazaretto Creek

Commander Whitton of Unshaken and his second-in-command, Second Lieutenant Herbert Patrick Westmacott, were later awarded the Distinguished Service Cross for having, among other things, “enforced the surrender of the Italian submarine Menotti, deliberately contravening the armistice regulations“; three sailors (including Petty Officer Samuel Joseph Lindop Evans) received the Distinguished Service Medal and several others a “dispatch mention.” Some British publications claim that the Unshaken “captured” Menotti, but this statement leaves the time to be found, since the supposed “capture” took place after the armistice, and after Menotti, like every other Italian unit, had received orders to cease hostilities against the Allies. The above-mentioned motivation of the SDC appears to be closer to the truth, beyond the alleged “deliberateness” of Menotti in the failure to comply with the order to go to Malta (the result, more than anything else, of the legitimate uncertainty that reigned at that time in the minds of many Italian commanders, who suddenly found themselves faced with such a sudden change in their situation).

To tell the truth, then, according to the Italian version, Menotti was actually carrying out the orders received from the submarines deployed in the Ionian Sea, which had received orders to head for Augusta (Syracuse is a short distance away and was also in British hands) and so they did (among others, they reached Augusta Vortece, Squalo, Bragadin, Onice, Settembrini and Zoea), then reaching Malta after a few days. In fact, the biggest discrepancy between the Italian and British sources is precisely the destination chosen by Commander Manunta. According to the former, Menotti was sailing towards Syracuse when it was intercepted by H.M.S. Unshaken, while according to the latter it would have been intended to reach Brindisi.

The commander of the Italian fleet interned in Malta was Rear Admiral Alberto Da Zara, the most senior of the divisional commanders who arrived there with the fleet after the death of Admiral Carlo Bergamini on the battleship Roma. When he was informed of what had happened to Menotti and of his situation, Da Zara protested energetically to Admiral Andrew Browne Cunningham, commander of the Mediterranean Fleet, who ordered the submarine to be returned immediately to the Regia Marina. Menotti then returned under full Italian control, mooring, on September 13th, at St. Paul’s Bay, together with the seaplane support ship Giuseppe Miraglia, the destroyer Augusto Riboty, the torpedo boats Libra and Orione and the submarines Atropo, Fratelli Bandiera and Jalea.

However, it seems likely that a consequence of this episode was the replacement of Commander Manunta, perhaps under British pressure, since a month later he was no longer in command of the Menotti, replaced by Lieutenant Enzo Mariano. On the other hand, two months later Manunta was again in command of a submarine, the brand new Vortice.

September 21st, 1943

Menotti was temporarily stationed in the mooring of San Paolo (Malta), together with ten other submarines (Alagi, Brin, Galatea, H 1, H 2, H 4, Jalea, Onice, Squalo and Zoea; later also the Turchese), under the “dependence” of the seaplane support ship Giuseppe Miraglia (this is the “San Paolo Group”, one of the two groups into which the Italian submarines arriving in Malta were divided: the other, called “Gruppo Marsa Scirocco”, is located in that locality under the command of the battleship Giulio Cesare).

October 13th or 16th, 1943

Following Italy’s declaration of war on Germany, Menotti (Lieutenant Enzo Mariano) left Malta at 08.30 AM together with the submarines Atropo, Corridoni and Zoea, bound for Haifa (Palestine).

Since the Italian garrisons of some of the Dodecanese islands, reinforced by British troops, were still resisting German attacks, these submarines were sent to Haifa to be employed in missions to supply weapons and ammunition to these islands (as well as to evacuate wounded on their return). in particular, the British requested the use of some Italian submarines for the supply of Leros on October 13th. Their estimated carrying capacity is 70 tons of ammunition or 40 tons of supplies.

October 21st, 1943

Menotti, Corridoni and Zoea arrived in Haifa in the morning, preceded by Atropos (which had arrived the previous day). There the Italian Higher Naval Command of the Levant (Maricosulev Haifa) was established, with a Submarine Group of the Levant (Grupsom Levante), under the command of frigate captain Carlo Liannazza; the Group’s submarines are under the command of the Royal Navy’s 1st Submarine Flotilla.

October 28th, 1943

Menotti (Lieutenant Enzo Mariano) left Haifa at 07:00 PM for a transport mission, carrying a load of ammunition and other supplies destined for the garrison of Leros.

October 31st, 1943

Menotti arrived in Portolago (Leros) at 10.50 PM.

Regarding the use of submarines to supply Leros, the official history of the USMM writes: “The actual contribution of the submarines were of course not of great importance, given their natural poor carrying capacity. They brought ammunition, gasoline, various materials, and even Bofors guns on deck. On the other hand, the moral contribution that the nocturnal visits of the smg. The Italians gave the defenders of Leros for the satisfaction and prestige that they derived from this Italian military activity. In fact, it was carried out without any British control (except for a representative of the Allies for the communications service), despite the fact that the submarines in full war gear and ready to fight during the crossing, which was, for the most part, carried out with covert navigation.” Unloading operations had to be carried out at night, because it was only in the dark that the Luftwaffe suspended its continuous air attacks.

November 1st, 1943

After unloading the cargo, Menotti departed Portolago at 02.27 AM

November 5th, 1943

Menotti arrived in Haifa at 04:21 AM.

December 3rd, 1943

With the fall of Leros and Samos, the need for submarines for transport missions disappeared, and thus Menotti left Haifa at 5.35 PM to return to Italy.

December 10th, 1943

The boat arrived in Taranto at 01.47 PM.

1944-1945

Menotti was employed in the Eastern Mediterranean (Haifa, Alexandria, Malta and Tobruk) for the training of Allied anti-submarine units, during the co-belligerence, participating in numerous anti-submarine exercises.

June 7th, 1944

The only crewmember killed in the war among the crew of Menotti appears to have died on this date: Sergeant Helmsman Michele Matarese, 25 years old, from Monte di Procida.

Strangely, Matarese appears to have died in captivity in Germany (more precisely, in the hospital of Stalag VI D in Dortmund, due to illness, after having previously been a prisoner also in Stalag I A/EB in Ebenrode, in East Prussia), although Menotti was not captured by the Germans after the armistice. One can venture the hypothesis that on September 8th, Matarese was on the ground, e.g. on leave, and that he was captured and deported to Germany. He is buried in the Italian military cemetery in Frankfurt AM Main.

Summer 1944

Lieutenant Luigi De Ferrante tool command of te Menotti.

December 1944

A British “pink list” (published weekly, indicating the position of each unit of the Royal Navy and the allied or co-belligerent navies) dated December 12th, 1944 indicates Menotti as one of the “A/S Training Submarines” and indicates that it was stationed in Taranto at that time.

Menotti in Taranto moored next to Squalo

1945

Laid up.

February 1st, 1948

Removed from the roster of active vessels as per the provision of the peace treaty.

1949

Demolished.

Original Italian text by Lorenzo Colombo adapted and translated by Cristiano D’Adamo

Operational Records

| Type | Patrols (Med.) | Patrols (Other) | NM Surface | NM Sub. | Days at Sea | NM/Day | Average Speed |

| Submarine – Medium Range | 36 | | 22281 | 2800 | 180 | 139.34 | 5.81 |

Actions

| Date | Time | Captain | Area | Coordinates | Convoy | Weapon | Result | Ship | Type | Tonns | Flag |

| 04/19/1943 | | C.V. Ugo Gelli | Mediterranean | Strait of Sicily | | Machine Gun | Shot down | | Four-engine Aircraft | | Unknown |

Crew Members Lost

| Last Name | First Name | Rank | Italian Rank | Date |

| Matarese | Michele | Sergeant | Sergente | |