Millelire was a Balilla-class ocean-going submarine (displacement of 1,427 tons on the surface and 1,874 tons submerged). In the Second World War the boat carried out a total of 11 war missions (4 patrols and 7 transfers), covering a total of 5,121 miles on the surface and 927 submerged, and spending 57 days at sea.

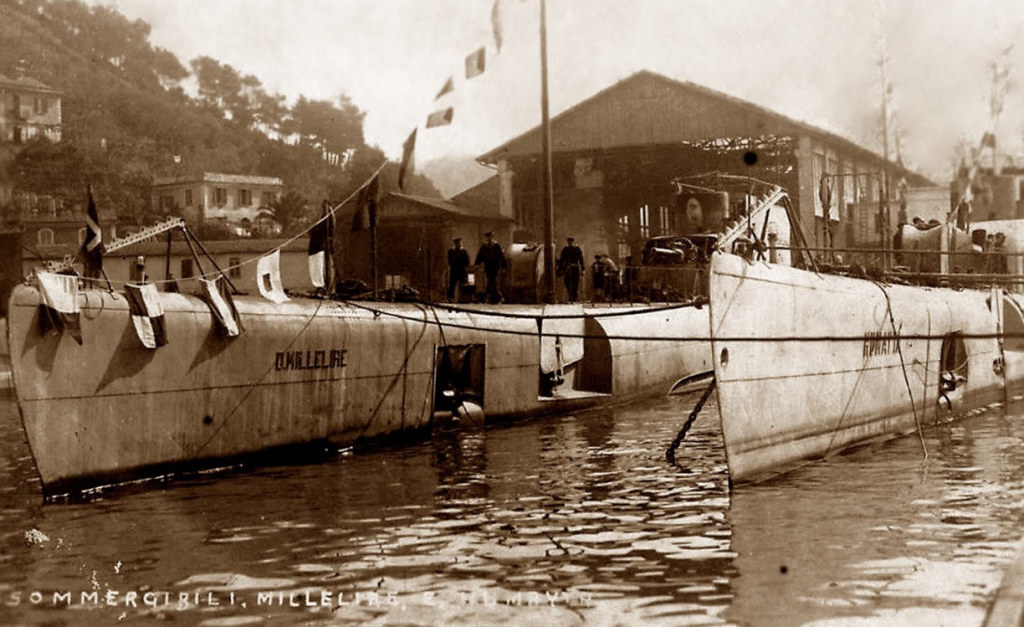

Millelire along the boat of the same class Humaytà built for the Brazilian Navy in Muggiano, 1927

Brief and Partial Chronology.

January 19th, 1925

Millelire was set up in the Odero Terni Orlando del Muggiano shipyard (La Spezia).

September 19th, 1927

The boat was launched at the Odero Terni Orlando del Muggiano shipyard (La Spezia). Godmother was Anita Susini-Millelire, great-granddaughter of Domenico Millelire after which the boat was named. During the tests, the submarine dove to a depth of 122 meters, 12 more than the maximum depth called for by the project.

August 21st, 1928

Millelire entered active service. With the twin boats Balilla, Enrico Toti and Antonio Sciesa the boat formed the I Submarine Squadron (called “large cruising” because it was composed of ocean-going submarines with great autonomy), based in La Spezia.

September 20th, 1928

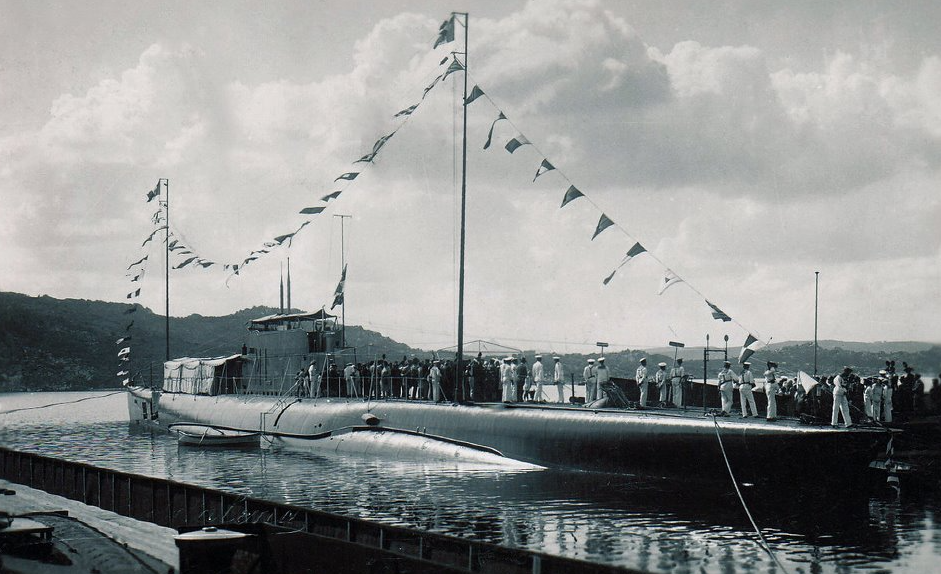

At 10.40 AM Millelire (Lieutenant Commander Carlo Savio) received the combat flag in a solemn ceremony in La Maddalena (Sardinia), the birthplace of the eponymous patriot, offered by the citizens of La Maddalena. The flag was delivered by a citizen committee chaired by retired Lieutenant Commander Paolino Spano, an elderly veteran of the Sardinian Royal Navy. The submarine was moored for the occasion to the east of the pier of Punta Nera, between this pier and the floating battery Faà di Bruno. The ceremony was attended by two great-grandchildren of Domenico Millelire, Anita Susini-Millelire and Francesco Romeo, as well as the maritime military commander of Sardinia, Rear Admiral Fermo Spano, other senior officers of the Maddalena stronghold, local civil authorities, some representatives of neighboring municipalities, local associations and numerous Maddalena residents.

Millelire receiving the combat flag in La Maddalena

The battle flag was blessed by the parish priest of La Maddalena, Antonio Vico, and then delivered to Commander Savio by Anita Susini-Millelire. For the occasion, the banner that had flown on the fort of Sant’Andrea back in 1793, during the victorious battle fought between the Sardinian garrison led by Domenico Millelire and the French attackers that included a young Napoleon, was also carried on board Millelire.

At the end of the ceremony, refreshments were offered on board to the authorities, and the public was granted a visit to the submarine, with a continuous influx of visitors throughout the day. In the evening, the officers of Millelire were invited to a dance party held in the Town Hall of La Maddalena. Earlier, Commander Savio had a bronze wreath made by the Arsenal of La Spezia (which was still located there) placed on the tomb of the eponymous hero of the submarine, in the Maddalena cemetery, with the dedication “The submarine Domenico Millelire to the Hero whose name it bears – September 1928“.

March 1929

The four Balilla-class submarines cruised to Lisbon. Millelire was the first Italian submarine to cruise in the Atlantic (except for those built in Canada during the First World War, which crossed the ocean for the delivery voyage). According to another source, Millelire, under the command of Lieutenant Commander Pietro Parenti, made the cruise together with the smaller submarine Goffredo Mameli, under the command of Lieutenant Commander Valerio Della Campana.

1930

Millelire and Toti travelled back to Lisbon. On July 15th, 1930, the crews of the two submarines were invited to a reception at the headquarters of the Italian Fascist Party in Lisbon. In this period, the commander of Millelire was the Lieutenant Commander Carlo Margottini.

March-October 1933

Together with the Balilla (Commander Valerio Della Campana, commander of the support group) and the gunboats Giuseppe Biglieri and Pellegrino Matteucci, Millelire (Lieutenant Commander Franco Zannoni) was used in the North Atlantic in support of the Decennial Air Cruise (or North-Atlantic Air Cruise; Orbetello-Chicago-New York-Rome, July 1st – August 2nd,1933) by Italo Balbo.

Millelire acts as a radio beacon, direction finding station and communication center, carrying out meteorological observations and communicating weather conditions to Balbo’s planes, crossing the entire Atlantic and arriving in the United States. In addition to these services, the presence of support units was also important for the eventuality of accidents or emergencies, which fortunately will not occur.

Given that the mission took place in stormy, foggy waters strewn with drifting blocks of ice, the General Staff of the Navy considered light cruisers and destroyers unsuitable for this task, as they were too “delicate” and with relatively limited range. On the other hand, the two Balilla-class submarines were chosen because of their great autonomy, their robustness, and their seaworthiness. The use of the two boats in the North Atlantic was also seen by the Navy’s top management as an excellent opportunity to verify the behavior of submarines and crews in extreme weather and sea conditions, and thus gain experience that may be useful in the event of war.

Balbo’s planes (25 Savoia Marchetti S. 55 seaplanes), taking off from Orbetello, stopped in Amsterdam, Londonderry, and Reykjavik (thus covering a total of 4,300 km), then cross the Atlantic from Reykjavik to Cartwright, Canada, with a journey of 2,400 km.

The Millelire in Boston, May 1st, 1933; in the background the gunboats Biglieri and Matteucci

(Leslie Jones/Boston Public Library)

It was precisely in the Reykjavik-Cartwright section, the most difficult (the northernmost route, at the limits of the autonomy of the planes of the time, previously crossed by other planes only five times, and only with an intermediate stopover in Greenland. Moreover, in a sea area characterized by frequent storms, persistent fog and drifting icebergs, the support of the naval units was decisive. The ships were arranged to form an “airway” (already tested, with satisfactory results, in the Londonerry-Reykjavik stage), with the use of a total of eleven units, all equipped with radios identical to those supplied with seaplanes as well as “Marconi” radio direction finders. In the first section of the route (Iceland-Cape Farewell) four chartered whalers were arranged for the crossing, while in the next stretch (Cape Farewell-Cartwright) five units were positioned, staggered at regular intervals (about 120 miles between one ship and another), in order: whaling ship San Sebastiano; Millelire; Balilla; Ticket holders; icebreaker Greased. Matteucci and Malaga whaler were instead sent to collateral observation points. Geophysicists embarked on some of the ships to perform meteorological observations.

Balbo’s air squadron took off from Reykjavik on 12 July 1933; The planes encounter fog and rainfall but were guided by the electromagnetic waves of the “airway”, flying over the different naval units positioned along the route one after the other: some were seen, while others, not visible due to fog and rain, were detected with radio direction finding measurements. Between 2.50 p.m. and 5.15 p.m., the seaplanes fly over Millelire, Balilla and Biglieri, whose crews wave their arms in enthusiastic greetings.

Once all in Cartwright, as scheduled, the seaplanes continue the cruise, stopping in Shediac, Montreal, Chicago, and New York, and then returning to Shediac, stopping at Shoal Harbour and crossing the Atlantic again, touching Ponta Delgada and Lisbon and finally arriving in Rome.

In addition to the function of supporting the aircraft involved in the flight, the cruise of Millelire and Balilla also allowed the Navy to test the oceanic qualities of the Balilla class, with results that were judged positive. In the “free” moments, when they were not engaged in weather surveys or communicating with aircraft, the two submarines carry out underwater navigation exercises and simulations of attack on the surface (with the cannon) and in the dive (with the torpedoes). From these experiences, the group leader Della Campana draws the following conclusions, which he indicated in his report: navigation on the surface in the part of the ocean crossed (almost at the limits with the Arctic) was rather difficult, and so was the work of the lookouts, who due to the prohibitive conditions cannot search and spot targets on the surface; Navigation at periscope altitude was possible, although with some difficulty, but observation at periscope was almost impossible; rough seas and frequent high waves at those latitudes would greatly disturb the launch of torpedoes, diverting them from the trajectory; The weather and sea conditions of the area crossed would not prevent navigation (which, however, would have to take place mostly underwater, emerging only to change the air and recharge the batteries), but would make offensive activity almost impossible.

In Chicago, Millelire and Balilla were visited with great interest by Italo Balbo, who then gave a greeting speech to the crews, finally greeting all the officers and sailors one by one at the end of the meeting.

May 1st, 1933

Millelire, Balilla, Biglieri, and Matteucci arrived in Boston.

August 22nd, 1933

Millelire, which was still in the United States, visited New York. It was the first foreign submarine to visit the major U.S. city since the end of World War I.

September 28th, 1933

On their return from the support mission of the air cruise, Millelire, Balilla, Biglieri, and Matteucci were visited in Civitavecchia by Benito Mussolini and the Minister of the Navy, Admiral Giuseppe Sirianni.

In total, Millelire covered 15,000 miles for the mission to support the transatlantic flight, calling at Madeira, Bermuda and all the main ports on the Atlantic coast of Canada and the United States. The mission, particularly demanding due to its long duration and the nautical and meteorological difficulties encountered, and always overcome, and the efficient assistance given to the aircraft (especially regarding radio links) earned praises to the commanders of Millelire and the other units involved.

1934

Millelire and Balilla made a cruise to Alexandria in Egypt, calling in the port of Piraeus on the outward journey and the ports of Italian North Africa on the return.

The Odero-Terni-Orlando 120/27 mm anti-aircraft gun mod. In 1924, due to its unsatisfactory performance, was removed. The weapon, together with those taken from Balilla, Toti and Sciesa, was destined for the anti-aircraft defense of Augusta and Messina. In its place, a 120/45 mm OTO mod. 1931, positioned on deck instead of in the conning tower as before (to increase stability). At the same time, the two single 13.2/76 mm anti-aircraft guns were replaced with two twin guns of the same type.

December 17th, 1936

The command of Millelire was assumed by the Lieutenant Commander Alberto Manlio Ginocchio.

1937

Millelire participated in the Spanish Civil War by performing two clandestine missions in support of the Nationalist forces. During these missions, the second lieutenant Gianfranco Gazzana Priaroggia, future ace of Italian submarines, served on Millelire as a navigation officer.

In the same years, Lieutenant Gino Birindelli, future Gold Medal for Valor, was the commander of Millelire, and in this period Lieutenant Luigi Longanesi Cattani, another future ace, was embarked on Millelire, and carried out his training for command there.

January 23rd, 1937

Millelire (Lieutenant Commander Alberto Ginocchio), part of the II Submarine Group of Naples, departed La Spezia to carry out its first clandestine mission during the Spanish Civil War.

In the second half of January, a total of twelve submarines (Millelire, Galileo Galilei, Enrico Tazzoli, Torricelli, Giovanni Bausan, Tito Speri, Ciro Menotti, Pietro Micca, Ettore Fieramosca, Otaria, Diamante and Jantina) were sent to the waters between Almeria and Barcelona, interdicting traffic to the ports of Republican Spain. Millelire was assigned to an ambush sector off the coast of Cartagena.

January 31st, 1937

The boat ended the mission by reaching La Maddalena, without having sighted any Republican ship.

August 31st, 1937

Millelire (Lieutenant Commander Giovanni Onis), now part of the I Submarine Group of La Spezia, departed from La Spezia for its second clandestine mission of the Spanish war: this time, the assigned sector was off the coast of Valencia.

September 6th, 1937

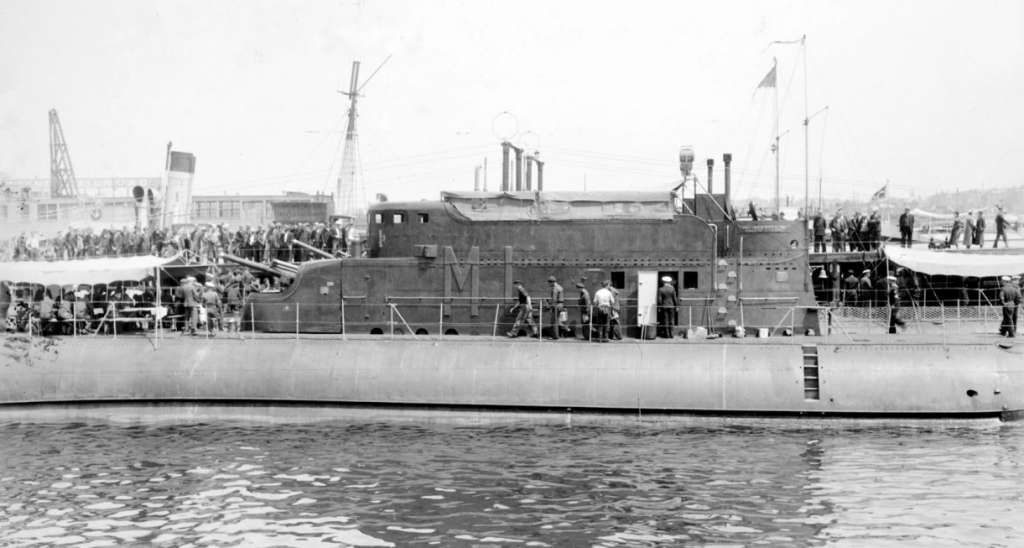

The boat returned to La Spezia without having encountered any Republican ship. Millelire with original identification code “ML”, was changed to “MI” after the entry into service of the new submarine Marcello (to which the letters “ML” went)

Millelire with the new identification code (pennant number)

1938

Assigned to the XV Submarine Squadron (I Submarine Group, based in La Spezia), composed of the largest submarines of the Regia Marina: Millelire and its three twin boats, the three units of the Calvi class – Pietro Calvi, Giuseppe Finzi and Enrico Tazzoli – and the Ettore Fieramosca.

May 5th, 1938

Millelire took part in the naval magazine “H” organized in the Gulf of Naples for Adolf Hitler’s visit to Italy.

June 10th, 1940

Upon Italy’s entry into the World War II, Millelire, together with Balilla, Enrico Toti and Antonio Sciesa, formed the XL Submarine Squadron (dependent on the IV Grupsom of Taranto), based in Brindisi (but according to a source Millelire was in Naples at the time of the declaration of war).

August 19th, 1940

Millelire set sail for his first war patrol, an ambush at the mouth of the Caso Channel, under the command of Lieutenant Commander Francesco De Rosa De Leo.

September 4th, 1940

The boat returned to base.

September 5th, 1940

When the British Mediterranean Fleet, returning from Operation Hats, entered the dredged channel to return to Alexandria, Egypt, the destroyer H.M.S. Hereward made sonar contact, and the British fleet made an emergency approach to thwart any launches. The submarine located by the Hereward, according to some sources, could have been Millelire, or the Giovanni Da Procida.

November 12th, 1940

In Taranto, Millelire, together with the tugboat Teseo, the factory ship Quarnaro and the water tanker Po, was among the units sent to assist the battleship Littorio, hit by three torpedoes during the famous night attack by British torpedo bombers (“Night of Taranto”). Millelire and Teseo flank the battleship torpedoed on the port side, while the Po was positioned on the starboard side.

November 14th, 1940

The boat went to patrol the Otranto Channel, protecting convoys carrying troops and supplies to Albania.

November 17th, 1940

At dusk, west of the Island of Fano, Millelire sighted an enemy submarine and fired two torpedoes at it, to no avail.

November 22nd, 1940

The boat returned to base.

December 13th, 1940

Millelire sets sail for the third was patrol in the waters of the Island of Fano.

December 17th, 1940

The boat ended the mission by returning to base.

1940-1941

According to a source, during the final days of a mission off the coast of Algeria, Millelire came across a small boat carrying the crew of a downed Italian CANT Z. seaplane (Lieutenant Pilot Cesare Palmieri), which was rescued. However, it does not appear that Millelire carried out missions in those waters, or that in general it carried out other war patrols in addition to those listed in this chronology, which is why an error about the name of the submarine is quite probable.

January 21st, 1941

Millelire was sent to lie in wait west of Pag (according to another source, in the Otranto Channel), returning to base at the end of the month.

1941

For a few months, Millelire was assigned as a training unit to the Submarine School of Pula, together with the Balilla and other older submarines of the Regia Marina (Toti, Des Geneys and others).

May 15th, 1941

Decommissioned and renamed G.R. 248, the submarinewas transformed into a floating fuel depot (G.R. means “Floating Refueling”, a term that identified the tanks for port use registered in the Register of Ships instead of that of the Navy roster).

According to other sources, it was laid up on April 15th, 1941, but this was an error: “Lost military ships” of the U.S.M.M. indicates the date of April 15, and it was also the most logical, given that Millelire was assigned the initials G.R. 248 following that (G.R. 247) assigned to the Balilla, which was disarmed on April 28th (this would not have been the case if Millelire had been the first to be decommissioned).

July-December 1941

The former Millelire was used to supply electricity during the recovery operations of the battleship Conte di Cavour, sunk by British torpedo bombers in the roadstead of Taranto the previous November. The energy supplied by the generators of Millelire and other units was used to power the pumps that expel the water from the hull of the sunken battleship, allowing it to be brought back to the surface.

Gasoline and latex

For about a year the G.R. 248 was used only for port use, but in the summer of 1942, while the fighting around El Alamein was raging in Egypt, the General Staff of the Navy, pressed by increasingly insistent requests for fuel from the German Command, decided among other things – together with the adoption of other measures to increase the amount of fuel sent to North Africa, such as the use of the auxiliary cruisers Barletta and Brioni and that of destroyers (which, however, took place only from the autumn) – to use Millelire to transport fuel to North Africa. Completely emptied of its internal equipment, traveling semi-submerged in tow of the destroyer Saetta (equipped with special equipment for fast trailers), the former Millelire could have transported about 1030 tons of fuel in its compartments-tanks (another source speaks of 600 tons of gasoline in cans) at a relatively high speed.

G.R. 248, formerly Millelire, while being used by Pirelli as a floating depot

The former submarine was thus subjected to heavy modifications: the conning tower, the main and auxiliary engines, the propellers and any other superfluous parts for the new use were eliminated, until an empty shell was left. The hull was then divided into watertight compartments, each of which would serve as a tanker, and the bow was modified to have a more hydrodynamic shape, which would allow the unit to be towed at a speed of 18 knots.

On 13 July 1942 the G.R. 248 “carried out” its first mission of this type, being towed from Navarino to Suda by the Saetta, escorted by the torpedo boat Pollux.

Two months later, at 8.45 AM on September 13th, 1942, the former Millelire left Taranto in tow of the Saetta (Lieutenant Commander Enea Picchio) carrying 690 tons of fuel (247 of gasoline and 443 of diesel) destined for Tobruk. Towing could take place at 14 knots, faster than most merchant ships of the time. Saetta and Millelire were escorted by the old torpedo boat Castelfidardo.

Arriving at Navarino at 11 AM on 14 September, the two ships and the submarine departed at 7:15 AM proceeding at 14 knots along the coastal routes of western Greece. During the voyage, the units were flown over by reconnaissance planes, but arrived unscathed in Tobruk at 10 AM. on 17 September.

At 04:00 PM on October 11th, 1942, the G.R. 248 left Tobruk again in tow of the Saetta (Lieutenant Commander Enea Picchio), in convoy with the motor ship Col di Lana. The strange convoy was escorted by the destroyer Freccia (Commander Giuseppe Andriani) and the torpedo boats Lupo (Lieutenant Commander Carlo Zinchi) and Antares (Lieutenant Commander Maurizio Ciccone). Between 00:00 and 01:40 2 October 12th, the convoy was attacked by bombers about seventy miles north of Tobruk; Around 01:00 AM Antares was hit by some bombs, suffering serious damage and losses among the crew (31 dead and 37 wounded), having to be taken in tow by Lupo, which took it to Suda (where they arrived at 01:00 PM the following day).

The rest of the convoy continued and, at 05:00 PM on the 12th, split: Col di Lana, Freccia and the torpedo boat Perseo (sent by Suda) headed for Piraeus, while the Saetta, with the former Millelire in tow, set course for Navarino, escorted by the torpedo boat Lira, sent by Suda. Destroyers, torpedo boats, and barges arrived at Navarino at 2:30 AM. Overall, the results of the use of Millelire for the transport of fuel in North Africa were judged to be positive.

When the Allies landed in Sicily on 10 July 1943, the former Millelire was on that island. Upon the U.S. occupation of Palermo, in July 1943, the wreck of the submarine-barge was found sunk in the port of that city. There it remained for two and a half years, until the war was long over, and on February 28th, 1946, the hull of the former submarine was brought back to the surface.

On October 18th,1946 Millelire was officially removed from the roster of the Navy but it did not go for demolition, it was instead purchased by the Pirelli Company, which transformed it into a barge-depot for the transport of rubber latex and used it in this function, moored alternately in Genoa or La Spezia (San Bartolomeo area).

In this new form (without a conning tower, and with a heavily modified hull), Millelire thus found itself to be the last submarine of the Regia Marina still in existence: the boats that had survived the conflict had all been scrapped in 1948 by the terms of the peace treaty, with the exception of Giada and Vortece. These two, after a long service in the Navy after the war, went through the blowtorch at the end of the sixties;. Even the few submarines that ended up in the hands of other navies for capture or transfer – the Greek Matrozos ex Perla, the French Narval ex Bronzo, the British P 711 ex Galilei, the Yugoslav Sava ex Nautilo, the Soviet S 32 ex Marea and S 41 ex Nichelio – had by then all been scrapped.

But the long history of Millelire also saw its epilogue at last. No longer considered useful even by Pirelli, in 1977 the last survivor of what had once been the second largest underwater fleet in the world was quietly scrapped.

Original Italian text by Lorenzo Colombo adapted and translated by Cristiano D’Adamo

Operational Records

| Type | Patrols (Med.) | Patrols (Other) | NM Surface | NM Sub. | Days at Sea | NM/Day | Average Speed |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Submarine – Oceanic | 11 | 5121 | 907 | 57 | 105.75 | 4.41 |