The Axum was an Adua-class (600 series, Bernardis type) coastal submarine (698 tons displacement on the surface and 866 tons submerged).

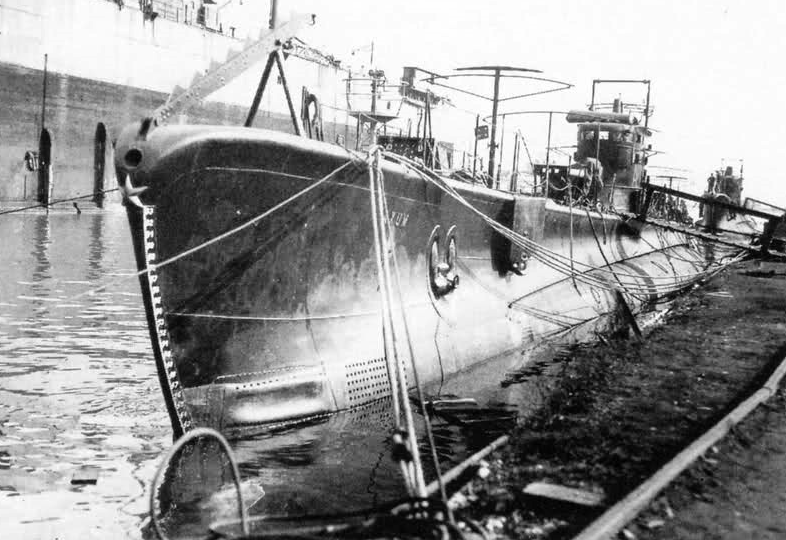

Axum in Monfalcone – 1936

(From the magazine “Rivista Marittima” n. 2 February, 1995)

During the war, It completed 27 patrols and 22 transfers, covering a total of 22,889 miles on the surface and 3,413 submerged, sinking a light cruiser of 4,190 tons and damaging a light cruiser of 8,530 tons and a tanker of 9,514 GRT.

Brief and partial chronology

March 8th, 1936

Setting up of the boat begun in the Cantieri Riuniti dell’Adriatico (C.R.D.A.) in Monfalcone (construction number 1178).

September 27th, 1936

The boat was launched at the C.R.D.A. in Monfalcone.

December 2nd, 1936

Axum officially entered active service.

March 20th, 1937

Placed under Maricosom (the command of the Italian submarine fleet), it was assigned to the XXXII Submarine Squadron based in Naples.

August 2nd through September 5th, 1937

The submarine carried out a secret mission in the Strait of Sicily as part of the Spanish Civil War but did not spot any suspicious ships.

1937-1940

It carried out intense training activities while based in Naples.

May 5th, 1938

Axum took part in the naval magazine “H” in the Gulf of Naples and in the simultaneous surfacing maneuver in formation of one hundred submarines, which then executed an artillery salvo.

June 10th, 1940

Italy entered the World War II. The Axum was formally part of the LXXI Submarine Squadron of the VII Grupsom homebased in Cagliari, with the twin boats Adua, Alagi and Aradam, but it was based in Naples. In the first months of the war, it was mainly deployed in the western Mediterranean.

June 1940

Sent to form a barrage south of Sardinia.

July 4th through 5th, 1940

Sent to lie in wait to the north of Algeria.

July 9th through 11th, 1940

Patrolling the island of La Galite, then transferred to the southwest of the island of Sant’Antioco (Sardinia).

November 9th, 1940

Axum sailed from Cagliari in the late afternoon bound for the waters off the island La Galite, where it had to form a barrage (along with the Aradam, Alagi, Medusa and Diaspro) to counter the British operation “Coat”, consisting of sending to Malta a convoy (of warships: the battleship H.M.S. Barham, the heavy cruiser H.M.S. Berwick, the light cruiser H.M.S. Glasgow and three destroyers, with a covering force consisting of the aircraft carrier H.M.S. Ark Royal – which will also launch a diversionary air attack on Cagliari – the light cruiser H.M.S. Sheffield and three destroyers) with troops and anti-aircraft weapons, as part of the complex operation “MB.8” (which also includes other secondary operations: the transfer of war units from Gibraltar to Alexandria, the dispatch of convoys to Greece, the attack of torpedo bombers against Taranto on 11th-12th November and an offensive against Italian convoys in the Otranto Channel). The five boats were positioned at 315° bearing from La Galite, 30 miles apart, with the task of carrying out night search by parallel routes without going more than 120 miles west of the line of formation.

Shortly after 7 PM on November 9th, Axum heard distant noises of turbines on the hydrophone, to the southeast, but at such a distance as to make any approach maneuver impracticable.

November 12th, 1940

It detected faint noises on the hydrophones.

November 27th, 1940

I was sent south of Sardinia, at 9.35 PM the crew sighted three destroyers and disengaged by diving.

January 1941

Sent to patrol in the waters off Algeria and Tunisia.

June 16, 1941

The Axum (Lieutenant Commander Emilio Gariazzo) was sent between Ras Uleima and Marsa Matruh, to counter, with other boats, the coastal bombardment operations by British naval units, in support of the retreat of British ground troops.

June 20th, 1941

Axum was ordered to move closer to Benghazi.

June 23rd, 1941

At 10:26 PM the crew sighted a ship heading west and launched a torpedo from 800 meters. It was defective (irregular run) and missed the target. The Axum launches a second torpedo, but this too misses the ship, passing a few meters aft. Spotted by the enemy unit, the submarine was forced to dive and subjected to a short but precise bombardment with depth charges, from which, however, it arises unscathed (the bombs explode very close, but the engines were stopped, all noisy activity ceased, and it dove almost to the bottom, finally managing to escape).

July 19th through 28th, 1941

The boat is sent on patrol off the coast of Tobruk, where it detects intense air and naval (surface) activity.

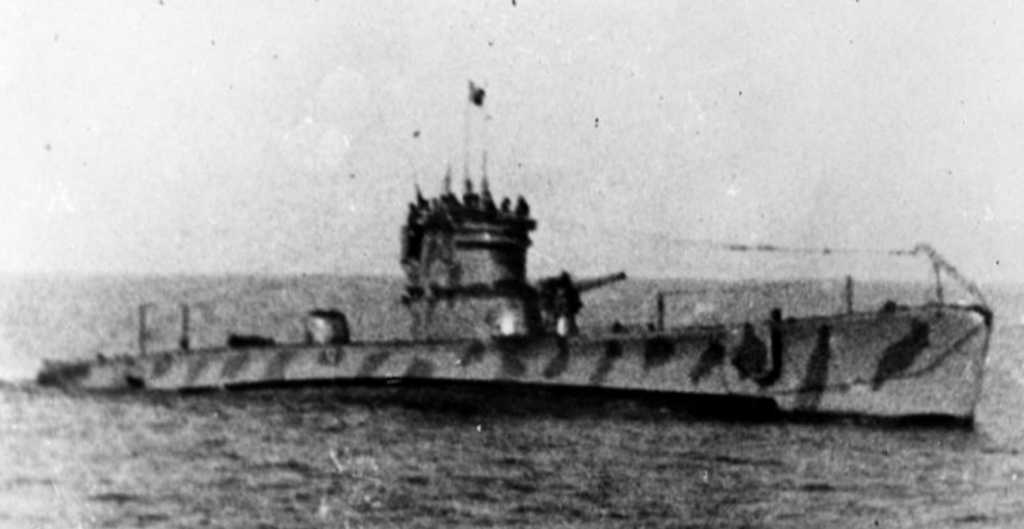

Axum at sea

(U.S.M.M.)

Summer 1941

Axum is sent to Leros (Greece), arriving nearby, it came to the surface near the island, sighted from land but mistakenly believed to be enemy, and therefore attacked by a MAS that opened fire with machine guns and launched a torpedo. Fortunately, the Axum was missed, there were no injuries, and the misunderstanding was clarified. Later, it transferred to Messina, then (September) to Cagliari.

September 1941

Sent east of the Balearic Islands and south of Menorca, for defensive purposes and along with three other submarines (Aradam, Diaspro and Serpente), during the British operation “Halberd” (consisting of sending a convoy to Malta, but which the Italian commanders believe could instead be a naval bombardment against targets on the coasts of the peninsula); However, the British squadron will not pass through the area.

October 24th, 1941

Sent on patrol in the waters off Malta.

December 1941

Sent on patrol in the waters of Cap Bougaroûn.

January 4th, 1942

Sent to lie in wait south of Malta (the ambush began at noon on January 4th), in the area between the meridians 14°00′ E and 14°40′ E and the parallels 34°40′ N and 35°00′ N, with the task of spotting and attacking any British naval forces that might be put to sea to oppose Operation “M. 43”, consisting of sending a large convoy of supplies to Libya. Such a threat did not materialize.

February 1942

Sent to lie in wait in Algerian waters.

Mid-June 1942

Axum is sent to lie in wait in the Ionian Sea during the Battle of Mid-June, to which it did not take part. Later it was sent to lie in wait northwest of Algiers.

June 22nd, 1942

Transferred to the waters off the Island Linosa.

July 15th, 1942

The Axum (Lieutenant Renato Ferrini) was sent to lie in wait between the Isle of Dogs and La Galite, and in the late afternoon, six miles east of the Isle of Dogs, it sights the British fast minelayer H.M.S. Welshman proceeding at high speed towards Malta (where it is headed with supplies). At 8 PM the Axum launched three electric torpedoes, under cover of darkness (but with the difficulty of rough seas, which prevented it from maintaining periscope depth), without being able to hit, due to bad weather that diverted the course of the torpedoes.

Mid-August

The Axum reached the brightest point of its “career” in August 1942, during the great air-naval battle of Mid-August.

After the substantial failure of the “Harpoon” and “Vigorous” refueling operations in the air-naval battle of Mid-June, two months earlier, the British commanders had in fact planned a new attempt to supply the exhausted garrison and population of Malta: “Operation Pedestal”. This was consisting of sending a convoy of 14 merchant ships (the cargo ships Almeria Lykes, Melbourne Star, Brisbane Star, Clan Ferguson, Dorset, Deucalion, Wairangi, Waimarama, Glenorchy, Port Chalmers, Empire Hope, Rochester Castle and Santa Elisa and the tanker Ohio) with heavy escort: four light cruisers (H.M.S. Nigeria, H.M.S. Kenya, H.M.S. Cairo and H.M.S. Manchester) and twelve destroyers (H.M.S. Ashanti, H.M.S. Intrepid, H.M.S. Icarus, H.M.S. Foresight, H.M.S. Derwent, H.M.S. Fury, H.M.S. Bramham, H.M.S. Bicester, H.M.S. Wilton, H.M.S. Ledbury, H.M.S. Penn and H.M.S. Pathfinder) to escort all the way, and four aircraft carriers (H.M.S. Eagle, H.M.S. Furious, H.M.S. Indomitable and H.M.S. Victorious), two battleships (H.M.S. Rodney and H.M.S. Nelson), three light cruisers (H.M.S. Sirius, H.M.S. Phoebe and H.M.S. Charybdis) and twelve destroyers (H.M.S. Laforey, H.M.S. Lightning, H.M.S. Lookout, H.M.S. Tartar, H.M.S. Quentin, H.M.S. Somali, H.M.S. Eskimo, H.M.S. Wishart, H.M.S. Zetland, H.M.S. Ithuriel, H.M.S. Antelope and H.M.S. Vantsittart) as additional escorts in the first half of the voyage (up to the entrance of the Strait of Sicily).

For their part, the Italian commanders had concerted adequate countermeasures: in the western and central-western Mediterranean, the convoy would have been subjected to a series of attacks by submarines, then, having arrived in the Strait of Sicily (under cover of night), by MAS and Italian and German motor torpedo boats (fifteen units in all), as well as incessant attacks by bombers and torpedo planes (in all, 784 aircraft) of both of the Regia Aeronautica (TN Italian Air Force) and the Luftwaffe, until their arrival in Malta. Also, it was planned the intervention (later aborted) of two cruiser divisions (the III and the VII) to finish what was left of the convoy decimated by the previous air, underwater and insidious attacks.

A total of 15 Italian submarines and two German U-boats contributed to forming a powerful submarine barrage in the western Mediterranean; the Axum was to form a barrier line of the western entrance to the Strait of Sicily, north of the La Galite- Skerki Banks junction (TN also known as the Skerki Channel), along with Alagi, Ascianghi, Avorio, Bronzo, Cobalto, Dessiè, Dandolo, Emo and Otaria. The orders, for all, were to act with great offensive determination, launching as many torpedoes as possible against any target, merchant, or military, larger than a destroyer.

On August 11th, 1942, the submarine, under the command of Lieutenant Renato Ferrini, left Cagliari for an area 25 miles northwest of Cape Blanc, where it arrived the following day. The boat thus became part of a barrage of eleven submarines, sent north of Tunisia (between Scoglio Fratelli and Skerki Banks) to attack the British convoy. In particular, the Axum positioned itself in the channel of Skerki Banks, together with Alagi, Bronzo, Dessiè and Granito (belonging to a different barrage): all, except the last, would achieve successes against the convoy.

At six o’clock in the morning of August 12th, the Axum arrived at the assigned spot and submerged. At 2 PM Commander Ferrini – considering, based on the signals of discovery, that the convoy would pass far close to the coast, keeping the naval formation assigned to its protection to the north – ordered to sail for Cape Blanc, with a 230° course, remaining submerged.

At 6:21 PM, the boat sighted in position 37°37′ N and 10°21′ E, on a 229° bearing (on the starboard side, very far away) and with an alpha angle of 11°, a dark mass that Ferrini, after studying it thoroughly, concluded to be a large merchant ship or an aircraft carrier. While approaching submerged to better understand what it was, at 6.40 PM the Axum sighted two smoke trails on the starboard side (295° bearing), and then the smoke produced by anti-aircraft fire against two aircraft, which were moving away to the east. Realizing that the British squadron must be there, at 6:41 PM Commander Ferrini steered to the north, to get closer, and at 6:50 PM, seeing that the smoke was now at a 300° bearing, he leveled off to 20 meters and headed at maximum speed for 30° bearing.

Returning to periscope depth at 7:27 PM, he sighted eight kilometers away portside, on a 110° angle (with an alpha angle of 290° and beta 10°), an enemy formation in position 37°37′ N and 10°19′ E. A minute later Axum approached starboard and assumed a course like that of the opposing formation, in order to better observe it. The captain found out that it was the convoy, about fifteen merchant ships, escorted by two cruisers and several destroyers. They proceeded in wedge-shaped formation in three lines of merchant ships, with the cruisers in the center and the destroyers all around in outer rows. There was also another ship, half-hidden from the others, which appeared to have two tall masts, like those of American battleships (TN hyperboloid lattice shell structures known within the service as cage masts), although there were no such units in Mid-August. At 7:33 PM, Ferrini noted that the British squadron had turned 30° to starboard, so he himself steered to starboard, but 180°. At 7:37 PM a new check showed that the distance had dropped to 4000 meters, the enemy formation had a course of 140° and a speed of 13 knots.

At this point, the Axum approached starboard (for 220° bearing) to assume a suitable position for launching torpedoes. At 7:42 PM, after a quick check at periscope depth, Ferrini brought his boat to 15 meters and ordered half speed forward to approach.

Returning to periscope depth at 7:48 PM, the commander noticed that he now had a 28° angle of sight for the second-row cruiser, which was preceded by a destroyer and followed by a large merchant ship.

At 7:55 PM, from an estimated distance of 1,300 meters from the first line of the convoy and 1,800 meters from the target cruiser (the position is variously reported as 37°26′ N and 10°22′ E, or 37°40′ N and 10°06′ E, 75 miles north of Cape Bon), Axum launched all four torpedoes from the forward tubes: First the number 1, straight, then the 4, angled 5° to starboard, then the 3, angled 5° to the left, and finally the 2, straight. Soon after, the boat disengaged.

After 63 seconds from the launch, a bang was heard; After another 27 seconds, two more, very close.

Ferrini thought he had hit a ship in the first row and then one in the second, but the reality was even better: not two, but three ships had been hit (all on the port side) with that single salvo of four torpedoes, the most brilliant result achieved by an Italian submarine in the Mediterranean.

A torpedo, the first to hit, had hit under the bridge the modern light cruiser H.M.S. Nigeria (Captain Stuart Henry Paton), displacement of 8,530 tons, flag ship of Admiral Harold Borrough (commander of Force X, assigned to the direct escort of the convoy), while advancing at 14 knots. The explosion opened a gaping hole thirteen meters wide. The forward boiler rooms were flooded, the pumps stopped operating, power went out to the entire ship, the rudder got stuck making the ship turn in circles, some contained fires broke out and 52 crew members lost their lives. To prevent sinking or capsizing, several bulkheads had to be shored up, the flooded compartments had to be insulated, and some others on the opposite side had to be flooded to reduce heeling.

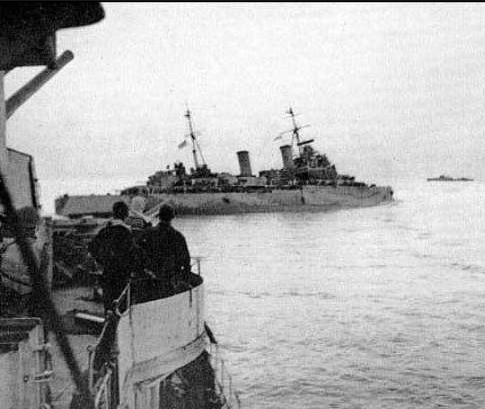

H.M.S. Nigeria heeled port side

(U.S.M.M.)

At 8:10 AM the cruiser, considerably heeled port side (the ship immediately listed 13°, becoming 17° after three minutes; later reduced to 5°), had to transfer Admiral Borrough to the destroyer H.M.S. Ashanti and then return to Gibraltar at 14 knots, escorted and assisted by the destroyers H.M.S. Derwent, H.M.S. Bicester and H.M.S. Wilton. Repairs took over a year and were not completed until September 1943.

Damage caused by the Axum’s torpedo

9U.S.M.M.)

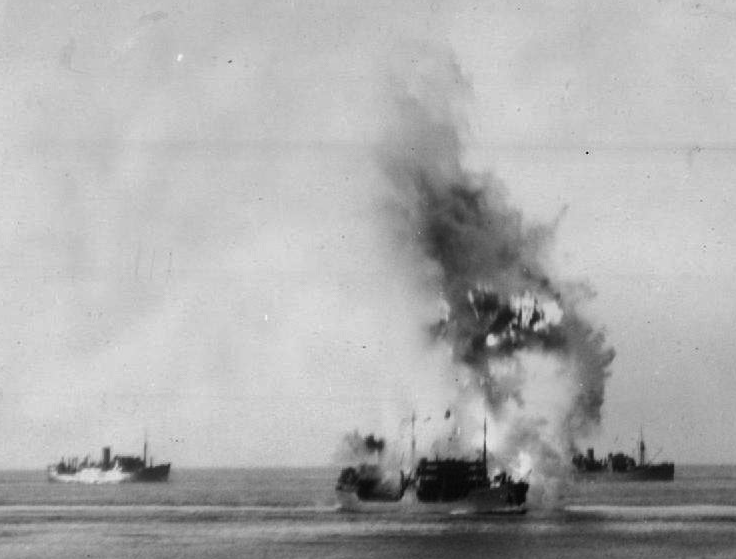

Two torpedoes had then hit the old anti-aircraft cruiser H.M.S. Cairo (of 4,190 tons, under the command of Captain Cecil Campbell Hardy) on the stern, portside, which at that moment was proceeding at 8 knots, removing the stern (including the port propeller) and causing the entire ship to lose electricity, as well as killing 24 members of its crew. After the evacuation of the crew, the Cairo (376 survivors), laid, ablaze and immobilized, and was finished off with cannon fire by the escort destroyer H.M.S. Derwent (another, H.M.S. Pathfinder, had already missed it with four torpedoes and launched some depth charges in vain to accelerate the sinking).

Finally, the fourth torpedo had hit the tanker Ohio (Captain Dudley William Mason), the most important merchant ship of the convoy (being the only tanker, with a vital cargo of fuel), amidships, causing heavy damage: a gash of seven by eight meters in the port side of the pump room (the explosion had also opened a leak on the starboard side, completely flooding the room, and the gash extended to the main deck), disabling the compasses and rudder transmissions (forcing the construction of an improvised emergency steering station at the stern), and the turning off the boilers (leaving it temporarily immobilized) and a violent fire on board. Within twenty minutes, the crew of the tanker managed to contain the fire and continue at 13 knots despite the damage. The ship was hit again by several air attacks (by bombs and even by a German Junker Ju 87 bomber which, shot down by machine guns, crashed on its bulwark), but the superhuman determination of its crew, towing by the minesweeper H.M.S. Rye and destroyer H.M.S. Bramham and support from destroyers H.M.S. Ledbury and H.M.S. Penn, which flanked her on each side, would eventually enable her to reach Malta on August 15th. Here it would eventually sink, breaking in two, after unloading the precious fuel.

The hit on the Ohio

The Axum attack would have had further negative implications on the convoy as H.M.S. Cairo and H.M.S. Nigeria were the only units of Force X equipped with personnel and equipment for coordination with the fighters of the air escort, and their disabling greatly weakened the effectiveness of the air escort, which could no longer coordinate with the convoy (thus facilitating the subsequent Italian-German air attacks, which claimed many victims). Moreover, the attack had occurred during the maneuver to go from a formation of four columns to one of two (to maneuver in narrower waters), which were to have H.M.S. Cairo and H.M.S. Nigeria at the head of each column: without guidance, without orders (during the time necessary for the transfer of Admiral Burrough from H.M.S. Nigeria to H.M.S. Ashanti, which in turn had to temporarily absent himself from its role as flotilla leader of the 6th Destroyer Flotilla) and almost half of the escort (since five destroyers had to be detached to assist the damaged cruisers), the convoy was temporarily plunged into chaos.

Four and a half minutes had passed since the launch when the reaction of the escort began. The Axum was 65 meters away when the first discharge of depth charges was thrown, which was centered. Ferrini brought his unit to 100 meters, then stopped every machine so as not to produce noises detectable by the hydrophones.

This was followed by two hours of anti-submarine hunting, very slow, with discharges whose accuracy varied from time to time. Whenever the Axum rose to 80-90 meters, the sonar beats could be clearly heard, always followed by the immediate launch of a barrage of depth charges. As a result, Ferrini decided to keep the submarine at depths between 100 and 120 meters, especially after that, at 9:35 PM, a destroyer was heard starting and moving from bow to stern, producing, in addition to the noise of the propellers, what seemed to be the noise produced by a darting cable, which made one think of the use of a towing torpedo.

After 10:15 PM it was noticed that there was another ship, further away, but even the one engaged in the hunt seemed to be finally moving away. In total, about 60 depth charges were dropped.

At 10:50 PM, the Axum emerged with a 330° bearing and sighted, three kilometers aft, a large ship on fire; another ship on fire, shrouded in copious smoke, at 45° on the starboard side; and a third already consumed by the flames, 70° from the stern (to port), from which a dense and grayish smoke was rising. The fire of the first ship lit the Axum all too well, and Ferrini saw not far away two destroyers in motion, which were beginning to make signals, he dived to avoid enduring a new hunt and thus was able to move away from the area to change air and recharge the batteries.

At 1:30 AM on August 14th, Axum emerged and moved away to the north, continuing to see a large fire in the distance, from which high flames rose from time to time in the sky.

Returning to dive at 6.10 AM, Ferrini found that the damage suffered in the hunt consisted of a loss of over 400 liters per hour, at a depth of 40 meters, from the trim box, a loss (at the same depth) of 700 liters per hour from the rapid dive tank, and minor losses from other cases. The leak from the AV tank prevented the submarine from diving more than 40 meters.

Ferrini decided to stay in the area. At 10.25 AM, having received an order from Maricosom to patrol a stretch of sea, he surfaced and set course for the assigned area, but at 10.50 AM a new order from the same Command made him submerge again, since it was likely that a British formation heading west would soon pass through the area (the remains of the convoy’s escort, which were now returning).

Between 11:45 AM and 1:30 PM, explosions were heard in the distance, without seeing anything, and at 3:50 PM the order was received to search for an aircraft carrier, so the Axum surfaced and proceeded on the surface for a 230° bearing, towards the indicated area. At 4.33 PM a further order led the boat to dive again, but the loss of the AV trim tank worsened; this did not induce Ferrini to leave the area, wanting to be able to attack any isolated and damaged enemy ships. At 8 PM order came to attack an isolated and damaged unit, so Axum resurfaced and set out in search of it. At 11:45 PM, while proceeding with on a 270° course, the crew saw in the distance, on a 110° bearing, the launch of two illuminating flares, and ten minutes later the launch of three more rockets, this time very close, aft. Immediately stopping the engines, Ferrini saw two more rockets landing lower, right on his vertical; He made a quick dive, clearly hearing the engine of an airplane, and when he was twenty meters deep he heard a bomb explode in the distance.

The loss of the forward trim tank prevented descending to more than 40 meters, so the Axum kept at this depth and moved away submerged in a northerly direction. Between 00:17 AM and 00:40 AM on August 14th, the crew detected suspicious noises on the hydrophones, which did not diminish even after the boat approached.

Resurfacing at 1:30 AM., the Axum lurked around again until 5:45 AM, when it dove again for the rest of the day, during which time it heard, at intervals, bomb discharges in the distance. Emerging at 9 PM, in consideration of the damage sustained two days earlier, Ferrini finally decided to return. Arriving at point “T 3” in Trapani at 7.30 AM on 15 August 15th, he followed the safety routes and moored at the submarine quay at 10.05 AM, thus concluding his victorious patrol.

The Battle of Mid-August, the largest air-naval battle ever fought in the Mediterranean, ended with very heavy losses on the Allied side. In the face of the loss, by the Axis, of the submarines Dagabur and Cobalt and about sixty aircraft, and the serious damage to the cruisers Muzio Attendolo and Bolzano, the British lost the aircraft carrier H.M.S. Eagle, the light cruisers H.M.S. Manchester and H.M.S. Cairo, the destroyer H.M.S. Foresight and nine of the merchant ships – all except Ohio, Rochester Castle, Port Chalmers, Brisbane Star and Melbourne Star – and complained of severe damage to the aircraft carrier H.M.S. Indomitable, the light cruisers H.M.S. Kenya and H.M.S. Nigeria and three of the surviving merchant ships (Ohio, Rochester Castle and Brisbane Star). However, the arrival in Malta of five merchant ships with 29,000 tons of supplies brought partial relief to the exhausted island, which was gradually able to regain its offensive capabilities.

October 1942

Sent to lie in wait in the waters off the Balearic Islands.

November 1942

Patrol off the Balearic Islands again.

November 7th, 1942

Axum sighted enemy units in position 37°14′ N and 02°23′ E, but was subjected to anti-submarine hunting and damaged, and the attack was thus prevented.

November 9th, 1942

Leave the assigned patrol sector in the evening and return to base.

February 1943

Patrol in the Gulf of Sirte to attack any enemy traffic.

April 1943

Sent to lie in wait northwest and then southeast of Cape Fer.

April 11th, 1943

While in the waters off Sardinia along with the submarines Argo, Velella and Acciaio, and navigating during a violent mistral wind, Axum took on a lot of water due to a sea gust and suffered the disabling of both periscopes, thus being forced to return to base.

June 21st, 1943

The Axum, while sailing from La Spezia to La Maddalena, was sighted at 1.20 PM, in position 42°35′ N and 08°38′ E (five miles northwest of Calvi, Corsica, while the Axum was proceeding on a 210° course) and from 3,660 meters away, by the British submarine H.M.S. Templar (Lieutenant Denis John Beckley). At 1.30 PM H.M.S Templar launched a torpedo from 1,370 meters, missing the target, and three minutes later (after regaining suitable depth, which had been briefly lost) launched four more, from the same distance. Avoiding the weapons from the Axum, the British boat launched two more at 1.40 PM, from a distance that had now risen to 2,750 meters, again without result. The Axum briefly spotted the attacker’s periscope but limited itself to evasive maneuvers without counterattacking with torpedoes from the stern tubes, because the distance was so short, and the weapons would not have had time to activate.

September 8th, 1943

When the armistice was announced, the Axum (Lieutenant Vittorio Barra) was in Gaeta, where it had arrived the same day from Pozzuoli (considered too close to the front) to carry out some repair work on the diesel engines (the original ones, now worn, had in fact been replaced with new German-made engines, but one of them failed during sea trials in the Gulf of Naples).

The announcement of the armistice was given to the crew, gathered in assembly, by Commander Barra. Many sailors, especially conscripts, rejoice for what they believe to be the end of the war and the imminent return home, while the career officers and non-commissioned officers, sensing what was really going to happen, were worried. Captain Barra brought the crew back to order, and for a few hours the activities on board continued as normally as every day.

September 9th, 1943

In the early hours of the 9th, German troops attacked the quay and overwhelmed the sentries, attempting to capture the moored ships (in addition to the Axum, some corvettes). At 2:15 AM, the men on the Axum saw more men running towards them in the dark, gesticulating and shouting to run quickly, because the Germans were occupying the harbor and capturing the ships at the mooring. Without wasting time in moving the gangway (which remains on the pier) and untying the moorings (which will be torn by the departing submarine), the only working diesel engine was immediately set in motion and brought to full force. In the haste to leave, the Axum slightly bumps into the corvette Pellicano, which was also fleeing.

Having escaped capture by the German forces, the submarine set course northwards, and at dawn, in the waters off Civitavecchia, it passed close to German patrol boats which, however, did not pay attention to its presence.

To buy time and understand what was happening, Commander Barra took the Axum to the island of Monte Cristo, where he spent the night in a cove.

September 10th, 1943

Axum reached Portoferraio (Tuscany), where numerous torpedo boats, corvettes and submarines from the ports of the Upper Tyrrhenian Sea had gathered. Admiral Amedeo Nomis di Pollone assumed command of these forces.

September 12th, 1943

Axum left Portoferraio bound for Palermo, still propelled by a single engine. According to the provisions of the armistice, black rims were painted at the bow and a black pendant was hoisted on the periscope. Due to its slow speed, the Axum remains alone on its journey, but it still managed to reach Palermo.

September 19th thought 20th, 1943

Axum departed from Palermo along with five other submarines (Filippo Corridoni, Nichelio, H 1, H 2 and H 4) and several surface ships (the torpedo boats Aliseo, Animoso, Ardimentoso, Ariete, Calliope, Fortunale, Indomito and Antonio Mosto, the corvettes Ape, Cormorano, Danaide, Gabbiano, Minerva and Pellicano, the auxiliary submarine destroyer AS 121 Regina Elena, the motor torpedo boats MS 35, MS 55 and MS 64, the submarine destroyers VAS 201, VAS 204, VAS 224, VAS 233, VAS 237, VAS 240, VAS 241, VAS 246 and VAS 248) and moved to Malta, where the boat moored next to the light cruiser Luigi di Savoia Duca degli Abruzzi (on board which the crew of the Axum went for meals, and on which men of the Axum would mount guard). The following day it was moored, along with the submarines Atropo, Fratelli Bandiera, Marcantonio Bragadin, Filippo Corridoni, Giada, Marea, Nichelio, Vortice and Luigi Settembrini in Marsa Scirocco, under the command of the battleship Giulio Cesare.

During the stay in Malta, there was no shortage of tensions; some career non-commissioned officers, not agreeing with the surrender to the Allies, exploited the discontent created among the crew for the theft of cigarettes from the rations on board and proposed seizing the small arms on board, with the intent, in fact, of seizing the submarine, but it did not happen.

October 9th, 1943

Axum left Malta (alone and four days earlier than the other submarines, given his lower speed) and returned to Taranto, still at low speed and with only one engine.

During the co-belligerence, once the engines were finally repaired, it was used in infiltration missions by spies and saboteurs, who landed on the Greek and Italian coasts occupied by German troops.

November 30th, 1943

Axum (Lieutenant Giovanni Sorrentino) departed from Brindisi at 4.20 PM for its first infiltration mission, with 15 agents of the OSS (Office of Strategic Services, precursor of the CIA) on board, some of whom were members of the “Vittorio” mission (in charge of setting up an information network in Rome).

Axum in Malta in a rare color picture of the time

December 4th, 1943

The agents in charge of the missions “Iris” (head of mission Captain Enrico Sorrentino, who will reach Rome) and “Syria” (led by the second lieutenant of artillery Arrigo Paladini, in charge of establishing radio contacts between the partisan groups operating in central Italy and the US forces; it was the first joint mission of the OSS and the ORI, the Organization for the Italian Resistance, disembarking in Pesaro; a sort of “secret service” of the Resistance). On the same day, the second chief signaler, Antonio Maddalozzo, who had joined the OSS, landed at Gabicce Mare (Cattolica) and reached Friuli to arrange for the delivery of supplies to the partisans operating in the area of Cismon del Grappa, as well as to collect information on concentrations and movements of German troops and on lines of communication.

December 8th, 1943

The “Pescia 2” mission of the OSS-ORI (radio telegraphist Giovanni Alberto Fabbri) was disembarked in Gabicce, then the return navigation began, during which, due to an engine failure, reached Taranto instead of Brindisi.

December 19th, 1943

Still under the command of Lieutenant Sorrentino, Axum sailed from Brindisi for the second special mission, consisting of the disembarkation of Greek agents of Force 133 of the SOE (Special Operations Executive), but was immediately forced to return by a failure of a diesel engine.

December 21st, 1943

Back in port.

The end

After surviving three years of hard war against the Anglo-American forces, without ever being seriously damaged and indeed reporting a remarkable success in mid-August, Axum was one of the few Italian submarines that were lost during the co-belligerence.

On December 25th, 1943 – after repairs to the engine failure were completed – the boat, under the command of Lieutenant Giovanni Sorrentino, left Taranto for a mission to recover informants in the Gulf of Arcadia (now Kyparissia), south of Cape Katacolon and the channel between Zakynthos and Morea.

After two days’ sailing, Axum arrived at the point indicated for the recovery of informers (west coast of the Morea) at eight o’clock in the evening of December 27th. When the pre-arranged signals arrived from land, the crew put to sea a dinghy under the command of a British officer. While waiting for the dinghy to return with the informants, the Axum began to move back and forth in front of the point, a short distance from the shore, but this led it to run aground on a rocky shoal not indicated in the mediocre nautical charts available (they were on a small scale, and a detailed hydrographic chart was missing), near the beach of Kaifas (TN Loutra Kaiafa) , in position 37°31′ N and 21°35′ E.

No maneuver was able to free it. The crew finally had to resign themselves and go ashore. All the removable material, weapons and ammunition on the submarine were removed and handed over to the Greek partisans. On the afternoon of December 28th, Commander Sorrentino placed the explosive charges intended to destroy his boat. In the early hours of December 29th, having obtained the consent of the British captain Peter (in charge of the mission), Commander Sorrentino, with a few other men remaining on board, lit the fuses and blew up the Axum.

Aware of the danger of the sea in that area, Sorrentino decided not to request the sending of a ship to recover its crew, but to move to a safer place for the rescue ship, even at the cost of having to spend time in territory occupied by German forces.

The Italian crew and Allied informants therefore had to take refuge in the Morea mountains, under the protection of Greek partisans, and spent a month there. On January 22nd, a Royal Air Force plane dropped winter shoes and clothing for them to enable them to cross the mountains. Finally, towards the end of January 1944, Italian sailors and British agents made a five-day march through the Morea Mountains, to reach Marathopolis, near the island of Proti. Here they were finally rescued by the escort torpedo boat Ardimentoso on January 29th, 1944, and brought back to Taranto the following day.

On January 22nd, German soldiers found the devastated and half-submerged wreck of the Axum on a beach 20 km southeast of Pyrgos. German divers had dived into it to finding it stripped of everything.

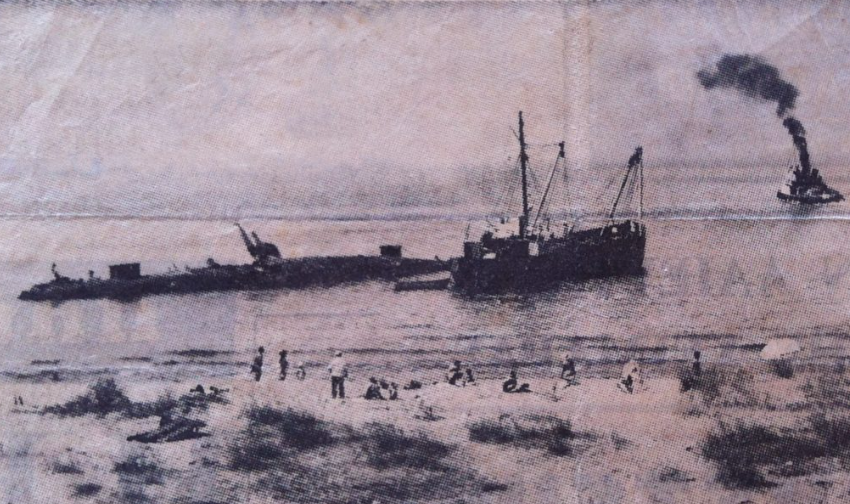

Relict of the Axum. Only the resistant hull is left.

(Phono N. Klimi)

It was left where it was. It remained there for several years, with the conning tower emerging from the surface, subject of visits by locals. What was left of the Axum was finally demolished in the 1950s (TN The actual date was 1971 and the boat was resurfaced and taken to Perama, near Piraeus, from scrapping).

Recovery of the Axum destined for ship-breaking

Giuseppe Bocci, second chief electrician, died in the metropolitan area on December 12th, 1942

Original Italian text by Lorenzo Colombo adapted and translated by Cristiano D’Adamo

Operational Records

| Type | Patrols (Med.) | Patrols (Other) | NM Surface | NM Sub. | Days at Sea | NM/Day | Average Speed |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Submarine – Coastal | 49 | 22889 | 3413 | 233 | 112.88 | 4.70 |

Actions

| Date | Time | Captain | Area | Coordinates | Convoy | Weapon | Result | Ship | Type | Tonns | Flag |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 8/12/1942 | 19.55 | C.C. Renato Ferrini | Mediterranean | 37°26’N-10°22’E | WS21S | Torpedo | Sank | HMS Cairo | Light Cruiser | 4200 | Great Britain |

| 8/12/1942 | 19.55 | C.C. Renato Ferrini | Mediterranean | 37°26’N-10°22’E | WS21S | Torpedo | Damaged | HMS Nigeria | Light Cruiser | 8670 | Great Britain |

| 8/12/1942 | 19.55 | C.C. Renato Ferrini | Mediterranean | 37°26’N-10°22’E | WS21S | Torpedo | Damaged | Ohio | Tanker | 9625 | United States |

Crew Members Lost

| Last Name | First Name | Rank | Italian Rank | Date |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bocci | Giuseppe | Chief 2nd Class | Capo di 2a Classe | 6/28/1941 |

| Poletti | Emilio | Naval Rating | Comune | 4/6/1942 |