On September 9th 1943, the day following the proclamation of the armistice, the Italian battlegroup, under the command of Admiral Carlo Bergamini, was attacked in the waters of the Gulf of Asinara by a formation of German bombers. During the attack, the ship was struck and the commander at sea, along with a great number of officers, petty officers and sailors perished, in all 1.253 men.

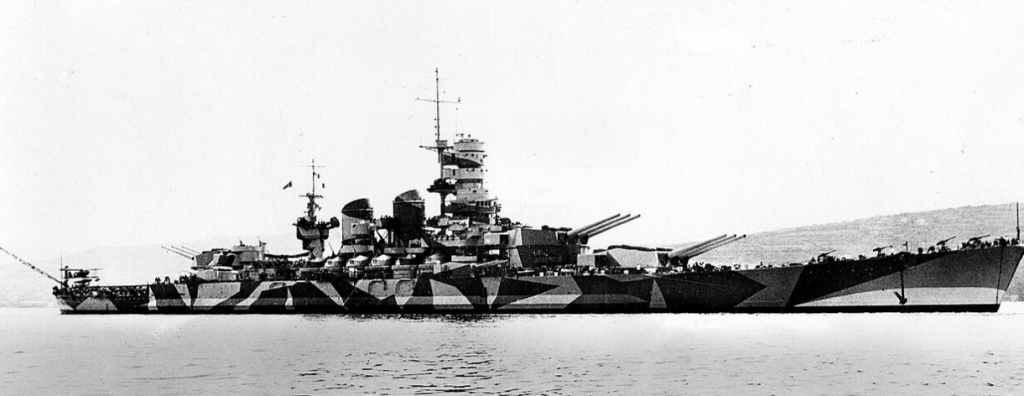

The battleship R.N. Roma in 1943

How did it happen? Why was the most modern and most powerful Italian battleships sunk by just one bomb? Why did so many loose their lives?

September 3rd, 1943. Gen. Castellano, on behalf of Marshal Badoglio and the Gen. Bedeli Smith, representing Gen. Eisenhower, secretly signed in Cassibile (Sicily) the so-called “Short Military Armistice”. The document was composed of 13 clauses and the fourth one called for «the immediate transfer of the Italian fleet and the Italian airplanes to those places that will be designated by the allied Command with the details of their disarmament, that will be decided by the Allied forces». Adm. Raffaele de Courten, Minister of the Navy, along with the commanders responsible of the other branches, was called by Prime Minister Badoglio, who informed them that «negotiations are in progress to conclude an armistice with the Anglo-Americans», but that the news must be kelpt absolutely secret.

September 5th, 1943. The Head of the Armed Forces, General Ambrosio, mentioned to de Courten that the conclusion of the armistice and its declaration were to be expected between the 10th and the 15th of September , probably on the 12th or 13th and that most probability the fleet would be relocated to La Maddalena (Sardinia), where the King would most probably come with the royal family and part of the Government.

September 6th, 1943. De Courten received confirmation from Ambrosio that such a course of action should be implemented if events hamper the actions of the government and the military leaders so recommend. Consequently, Supermarina ordered that the two destroyers, the Vivaldi and Da Noli be stationed in Civitavecchia at dawn on September 9th, ready to sail in two hours. Two corvettes were stationed in Gaeta, and two MAS in Fiumicino (near the estuary if the Tiber River). The morning of the 7th, De Courten called a meeting in Rome for all admirals reporting to the Naval High Command (Supermarina). By this time, he still did not know that the armistice had been signed on September 3.

More and more, evident signs predicted an allied offensive against the southern coast of Italy. Twenty submarines were deployed along the possible approach routes of the convoy and they were put in a state of alarm.

September 7th, 1943. De Courten called a meeting at the Ministry of the Navy. Attendees included the Naval High Commander, Adm. Carlo Bergamini. During the meeting, de Courten did not consider it opportune to inform all present of the negotiations in progress for the armistice because such information was considered highly secret. With the attendees, he defined a conventional signal that would be used to order the scuttling of the fleet.

September 8 th, 1943. As soon as confirmation of the beginning of the allied landing in Salerno was received, de Courten gave orders to the Commander at Sea, Adm. Carlo Bergamini, (who in the meantime had returned aboard the Roma in Spezia), to fire up the boilers and be ready to sail at 2:00 PM. Anticipating an offensive the following day, orders were given to coordinate operations with the Regia Aeronautica and the Luftwaffe.

De Courten was called by the supreme commander General Ambrosio, who informed him that the Allies had rejected the proposal to transfer the fleet to La Maddalena, but that they had allowed one cruiser and four destroyers to be left to the disposal of the King. Nevertheless, he added that he would continue to insist on the La Maddalena issue, and that he still hoped to succeed in convincing the Allies. Finally, he told him to wait for orders to leave La Spezia with the battle group in about six hours.

De Courten was then called to the Quirinale (Royal Palace) for a meeting directed by the King. Gen. Ambrosio informed the audience that the armistice had been signed on September 3 with the agreement that a specific day for implementation would be communicated based on the mutual operational needs of the Italian and the Anglo-American.

At 18:30, Radio Algiers releases the news of the armistice to the world.

At 19:45 Badoglio made the following radio announcement: “The Italian Government, recognizing the impossibility of continuing the uneven struggle against the overwhelming enemy power, with the intent of saving further and more serious calamities to the Nation, has asked Gen. Eisenhower, commaner in chief of the Allies forces, for an armistice. The request has been accepted. Consequently every action of hostility against the allied armed forces must stop from the Italian armed forces in every place. They (the Italian forces), however, will react to possible attacks of any other origin».

According to the clauses of the armistice, the Italian ships, bearing black circular panels in sign of surrender, would be to transferred to Malta to await their final destiny. The situation had been completely turned upside-down. A few hours before, the Regia Marina was prepared to go to sea and fight the Allies. Not even the commander. Admiral Carlo Bergamini, had been made aware of the developments of the political situation. The highest secrecy, desired by Gen. Vittorio Ambrosio, had had its results.

Adm. Sansonetti gave orders to the fleet to reach the agreed allied ports but without “deliverering of the ships and lowering of the flag”. To convince friends and enemies alike, he transmitted his orders in clear..

Gen. Ambrosio asked the Anglo-Americans that the Fleet, for technical reasons, be moved to La Maddalena and that everything be ready for the docking of the ships.

Aboard the ships the excitement reached a dangerous level. Bergamini had to issue orders forbidding anyone from boarding the ship without proper notification and authorization. “No one should ask for directives”, he announced, “They will come when needed”. In the end, it was decided to call all admirals and commanders to a meeting. It was 10 PM.

The departure of the fleet, given as imminent during the day, had been postponed several times. Tension amongst the crew was at its worst. Bergamini took the situation under control and confirmed to the admirals and commanders the news of the armistice and summarily mentioned his telephone calls with Rome. He reminded everyone of the supreme duty of obedience so paramount in such a dramatic time.

September 9th, 1943. At 3 PM the fleet left for La Maddalena. It did not hoist the black signs of the surrender. At the same time, in the Gulf of Salerno, the Anglo-American operation “Avalanch” had begun.

Three battleships left La Spezia: the Roma, with Adm. Bergamini aboard, the Vittorio Veneto and Littorio (renamed Italia after July 25, 1943) with Adm. Garofolo. Three cruisers (Eugenio di Savoia, Adm. Oliva; Montecuccoli and Regolo) and eight destroyers (Legionario, Grecale, Oriani, Velite, Mitragliere, Fuciliere, Artigliere and Carabiniere). The Fleet was maintained at about twenty kilometers from the western coast of Corsica at a speed of 22 knots. At dawn, an allied plane spotted the fleet. At 8:00 AM Adm.. Meendsen Bohlken, commander of the German forces in La Spezia, gave the alarm to Berlin: «The Italian fleet has departed during the night to surrender itself to the enemy».

At noon on the 9th the Fleet , with the ships in a line formation, was in sight of the Bocche di Bonifacio. Bergamini took a 90-degree left turn toward la Maddalena, but at 13.40 PM he received news that La Maddalena had been occupied by German forces. Without hesitation, Bergamini reversed course 180 degrees.

At 2:00 PM, Bergamini was in sight of the Asinara. Meantime more reconnaissance planes were spotted. Unexpectedly, from five thousand meters, airplanes dropped a few bombs without striking any of the ships

From lstres (Marsiglia) 15 two-engine Donier 217 KIIs from the 3rd Squadron of the 100° group took off. Each airplane was equipped with a type FX-1400 bomb. This bomb had been designed in 1939 by Doctor Kramer and was originally named FritzX. The FX-1400, which was also knows as the SD 1400, was a high penetration 1400-kilo device with four small wings, tail controls and a rocket motor. Near the tail a remote control system was also installed. The control was operated by the airplane from which the bomb had been launched. The bomb, with 300 kilograms of explosives, was 3,30 meter long .

At 15.30 the first bomb was directed toward the Littorio (named Italia after July 25 1943) and it fell near the battleship temporarily blocking the rudder. The ship was then controlled with the auxiliary rudder. The point of the attack was about 14 miles southwest miles of Cape Testa (Sardinia).

The rocket bombs were a great surprise. Not only were they extremely precise, but the fact that they were dropped at 60 degrees instead of the usual 80 created confusion. This new technique tricked the Italian officers into believing that the German intentions were not offensive. This mistake was fatal, considering that the Italians were under order to fight back only if attacked.

Only after a demonstration of such evident hostility from the Germans, did the Roma give the signal of «air alarm». The antiaircraft batteries, first from the right, then from the left, opened swift fire, but it was too late! The airplanes were just above the ships and in that position they were safe.

At 15.45 the Roma was hit on the right side. The bomb burst into sea after having crossed the whole hull and the ship’s speed was reduced to 10 knots.

At 15.50 the Roma was struck again by a second bomb. This one exploded in the forward deposits of the big caliber complexes. The ship was fatally wounded. A column of flames and smoke rose for a thousand meters. The turret n. 2 (1.500 tons) along with all of its occupants and the command tower were projected aloft and tilted to the right side. It was the end for Bergamini and his staff. The ship began to tilt to the right side. It was a horrendous show of death and destruction. The majority of the men were burnted alive.

At 16.12 the Roma turned upside-down, br