he submarine GEMMA was one of the 10 boats of the “PERLA” series, part of the class “600” of coastal submarines. This successful series, just like whole class “600”, was built by the C.R.D.A. shipyard (6 units) of Monfalcone (Gorizia) and O.T.O. (4 units) of Muggiano (La Spezia) between 1935 and 1936.

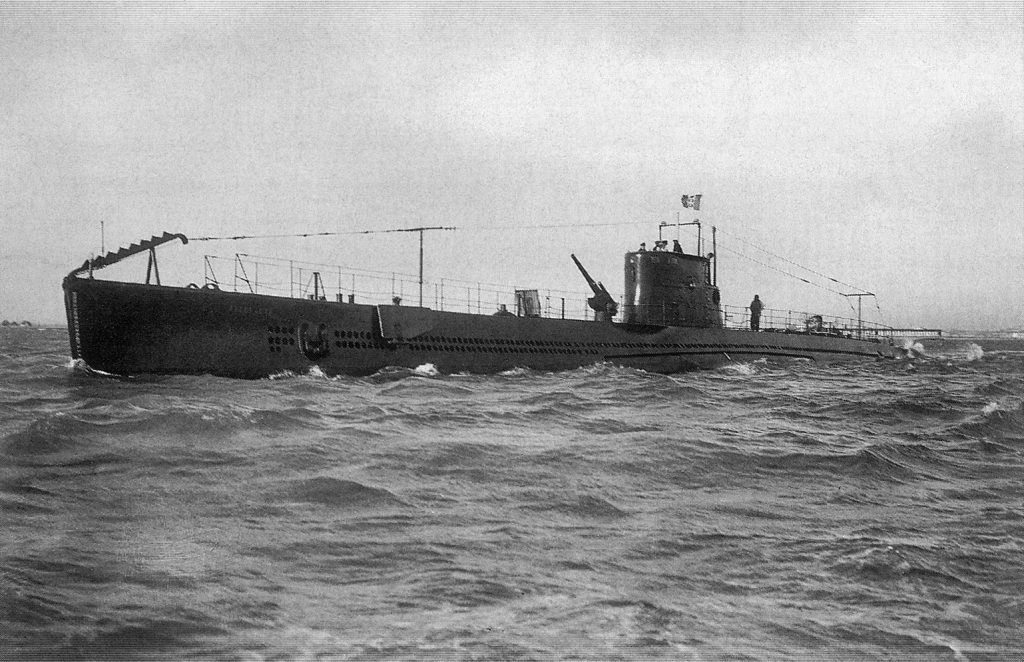

The GEMMA in the early days

(Photo courtesy Erminio Bagnasco and Achille Rastelli)

The GEMMA belonged to Monfalcone’s group and was laid down on September 7th, 1935, launched on May 21st, 1936 and delivered to the Regia Marina on July 8th of the same year.

Operational Life

Upon entering service, the GEMMA was assigned to the 35th Squadron, based in Messina. From here, it completed a long cruise of the Italian islands in the Aegean Sea, repeating it in 1937. Under the command of Lieutenant Carlo Ferracuti, the GEMMA participated in the Spanish Civil War with a patrol off the Sicilian coast lasting nine days, from August 27th to September 5th, 1937.

In 1938, the GEMMA was assigned to the Red Sea, in Massaua. From this base, along with the PERLA, in spring of 1939 it completed long cruises in the Indian Ocean to test, during the monsoon, the sea worthiness and operation of the boat. From the mission reports, in addition to the navigational issues (sea force 9, inability to use the weapons or keep periscope depth), surfaced the danger of the air conditioning systems. The gas used, methylchlorid, was found to be toxic and would cause great problems with the boats so equipped.

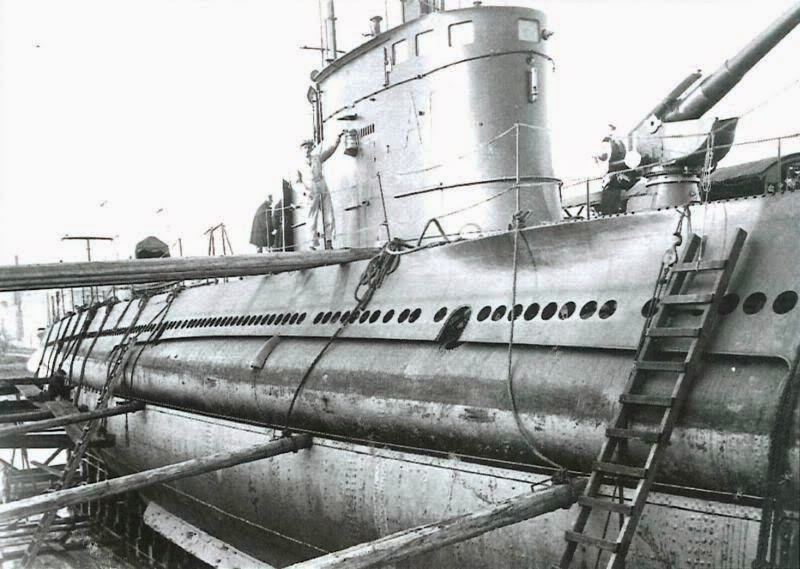

The GEMMA still being fitted

(Photo Turrini)

Having returned to Italy toward the end of 1939, the GEMMA was assigned to the 14th Squadron, 1st GRUPSOM based in La Spezia. After Italy’s entry into the war (June 10th, 1940), while still part of the 1st GROUPSOM, the boat was transferred to the 13th Squadron under the command of Lieutenant Commander Guido Cordero di Montezemolo and relocated to Leros, the Italian naval base in the Aegean Sea.

The initial fruitless missions took place:

From June 10th to the 15th, 1940, in the waters off Khios.

From June 30th to July 8th, 1940 off Sollum, along the Egyptian coast

From the 7th to the 16th of August, 1940, north of Crete.

On September 30th, the GEMMA left for the fourth war mission with the assignment of patrolling, from the 1st to the 8th of October along with the AMETISTA and TRICHECO, the Kassos Channel (East of the Island of Crete).

The area of the passage was divided into three areas – north, center, and south – assigned in the same order to the GEMMA, AMETISTA, and TRICHECO. After two fruitless days, on the 3rd of October only the GEMMA was ordered to the east to patrol the area between Rhodes and Scarpanto (Karphatos) (to be more precise in the square defined by the Island of Seria and Cape Monolito (Rhodes), Cape Prosso (southernmost point of Rhodes), Cape Castello (southernmost point of the island of Scarpanto), until the evening of the 8th. It was precisely in this area that on the night of the 7th a tragedy took place.

The night of the 7th, the TRICHECO (Lieutenant Commander Alberto Avogadro di Cerrione), a day before completing its patrol, had left its assigned area south of the Island of Kassos because of a wounded person aboard, and it was navigating along the western coast of Scarpanto, thus in the area occupied by the GEMMA.

Due to a fatal mishap with radio communication, neither the GEMMA nor the TRICHECO were informed of each other’s movements. In addition, a message in cipher dated the 6th in which Leros, via SUPERMARINA, ordered the GEMMA to immediately return to base, was never transmitted by the central operating office. Around 1:15 on the 8th, the TRICHECO sighted a profile of a submarine and, unaware of the presence of an Italian boat in that area, and assuming that such a presence would have been signaled, believed it was an enemy submarine. This situation, with the equipment available at the time, did not leave time to attempt recognition: only the submarine that fires first survives.

Thus, around 1:21, the TRICHECO launched two torpedoes. The distance was close: impossible to miss the target. The GEMMA, hit midship, sank immediately in position 35 30’N, 27 18’E, three miles for 078 off Kero Panagia, not too distant from the City of Scarpanto. No one survived. The opposite could have taken place if the GEMMA had sighted the other submarine first. These are accidents that, unfortunately, take place in all wars and all Navies.

Anyway, such danger for the Italian Navy was very limited. As a matter of fact, Italian naval doctrine was based on the concept of “ambush war” and each boat was assigned a small square of sea from which it was absolutely not allowed to trespass, remaining in waiting for enemy ships. This tactic, inherited from the experience of WW I, proved unsuccessful.

The Germans, on the other hand, since the beginning adopted a method which we could describe as “guerre de corse”: the area assigned to each boat was relatively large and they would pursue ships. After a sighting, all the boats within reach were called to concentrate on the target (often a convoy), forming a “wolf pack”. Operating in this way, the risk of friendly fire was high, but the Germans took it into consideration.

Translated from Italian by Cristiano D’Adamo