We have repeatedly mentioned September 8: this tragic day, that had grave consequences for the Armed Forces and for all of Italy, obviously had some consequences also for merchant ships, especially those that were in the North of the country. On September 9, the order was transmitted from Rome to the port authorities of the entire country, to ship owners and captains, to make all efforts to prevent the Germans from seizing all vessels that could be employed against the United Nations, and to adhere to any requisition requests made by Allied Commands out of necessity.

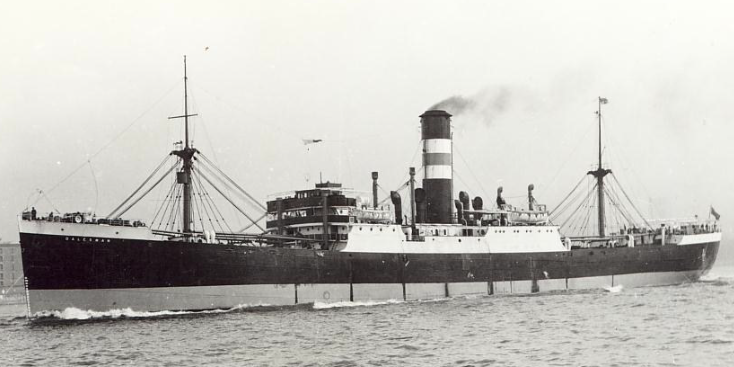

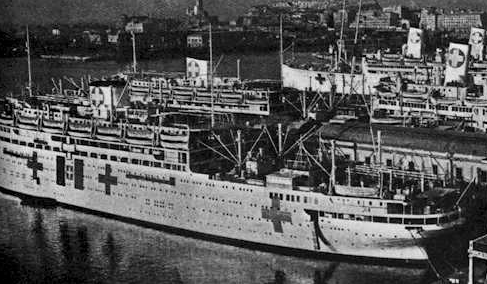

The Cattaro scuttled by its crew in Santa Margherita Ligure to avoid capture

(Photo Giuliano Gotuzzo)

In Northern Italy, this second part could not be carried out, because there was no time to execute the first part: few units self-destructed or were sabotaged, almost none was able to reach Southern Italian ports, in particular those in Apulia and Sicily, the only regions that had already been liberated.

Some ships made an effort: the motor vessel Vulcanici left Trieste the morning of September 8 headed for Pola where she was due to embark reserve officer candidates. The evening of September 10 the school Commandant, Captain Enrico Simola, decided that it would not be prudent to sail with a crew of questionable loyalty and hundreds of green young men.

The next day he got all officer candidates off the ship (most of them ended up interned in Germany) and purposely ran the ship aground near the Island of Brioni, ordering it to be sabotaged; but the order was not carried out.

On September 17, the motor vessel Vulcanici was seized by the Germans, floated off and taken to Venice, loaded with Italian soldiers evacuated from Pola; she spent the remainder of the war idling in Venice.

This fate was shared by many ships seized by the Germans: considered useless for war purposes, they were abandoned or purposely sunk as barriers in harbors; this happened, for instance, to the passenger liner Marco Polo in La Spezia, or to the ocean liner Augustus in Genoa, where she was waiting to be transformed into the aircraft carrier Sparviero.

The ships the Germans did use were taken – except for a few inducted directly into the Kriesmarine – through mandatory leasing contracts, after a short period during which they were all considered war booty, and embarked personnel were removed and replaced with German seamen.

Later, the property of the ships that had not attempted to escape capture or had not been sabotaged was recognized: the war booty principle, however, still applied to hospital ships or for ships registered as auxiliary shipping of the Italian State. With these exceptions, Italian ships were returned to their owners, but forcibly leased to the Mittelmeer Reederei. Nevertheless, few ships actually served: Italian sailors did not enjoy sailing aboard German-requisitioned ships.

Many of them were deported, some tried to avoid being embarked either by not obeying the call-ups, or deserting when forcibly embarked. Resistance and desertions reached such proportions that in April 1944 the German Administration filed a formal complaint with the Republic of Salò, which for its part, tried, insofar as it could, to protect the seamen from German reprisals and to safeguard the ship owners’ interests.

In October 1944, after prolonged discussion, the private property of the ships, even if requisitioned, was recognized, along with the owners’ entitlement to be paid all amounts due for the ships’ employment in war.

However, in March 1945 the Germans denounced the agreement and no more dues were recognized to the owners. It should be recalled that, throughout the time the ships remained under German control, their owners and the R.S.I.’s authorities were almost always forbidden from boarding them.

At the end of this difficult time, in May 1945, almost all Northern Italian ports were full of wrecks, due both to Allied bombings and to the havoc wreaked by the retreating Germans: the conclusion was that the Italian Merchant Marine had practically ceased to exist, and a long time would have to go by before anyone could speak of ship borne traffic under the new flag.

Translated from Italian by Sebastian De Angelis