The MARCONI was the first of a series of 6 boats and which bears its name (Marconi Class). Of this class, 5 boats were sunk and one captured. The boat was laid down at the C.R.D.A. shipyard of Monfalcone on September 19th, 1938, launched on July 30th of the following year, and delivered to the Navy on February 2nd, 1940. After a brief period of training and testing, the boat was assigned to the 22nd Squadron, 2nd Submarine Group with its base in Naples.

The MARCONI still on the slip just before its launch

(Photo USMM)

Operational Life

1940

The first war patrol of the submarine MARCELLO was particularly successful. In July 1940, a few weeks after Italy’s declaration of war, the Italian Submarine Command organized a large and continuous patrol line east of the Strait of Gibraltar. The area in question was patrolled by a total of 11 boats divided into 3 groups. The MARCELLO, along with the Emo, Dandolo and Barbarigo, was assigned to the first group. This patrol started on July 1st and lasted for almost two weeks. The Emo and MARCONI were assigned to the westernmost area. The Emo patrolled south of the meridian of Alboran (about halfway between the Moroccan and Spanish coast), while the MARCONI was assigned north of this meridian and closer to the Spanish coast.

The MARCONI receiving final touches before being delivered to the Navy

(Photo USMM)

The MARCONI, under the command of Lieutenant Commander Giulio Chialaberto, was already in position when, the evening of July 2, it sighted in position 36° 25’N, 03° 48’W a group of six destroyers. In the darkness of the night (it was about 30 minutes to midnight), the captain launched a single torpedo at about 1,000 meters from the nearest target. The weapon failed right away, assuming the wrong course, so a second weapon was also expended. The presence of such a large formation forced the MARCONI to seeking refuge in the depths of the sea, thus the results of the attack could not be immediately ascertained. Later reports would confirm that as a result of this action, H.M.S. Vortigen (D37) was hit and sustained damage, but was able to get back to base. H.M.S. Vortigen, a British destroyer of the V Class built in 1916, would eventually be lost on May 15th, 1942.

Toward the end of the patrol, on July 11th (possibly earlier), the MARCONI sighted another destroyer. After having made contact around 03:00, the captain moved the boat into a favorable attack position and launched a single torpedo. The weapon hit the British destroyer H.M.S. Escort which, along with H.M.S. Forester (H66), was returning to Gibraltar following operation “MA 5”. The attack took place in position 36° 20’N, 03° 40’W and, following the attack, the MARCONI had to avoid an attempted ramming by H.M.S. Forester. H.M.S. Escort was a destroyer of the E class built in 1933 and following the attack that had destroyed the forward boiler room, there was a failed attempt to tow it back to port.

Upon returning to Naples, the MARCONI was one of the earlier boats selected for service in the Atlantic. At the end of August, MARCICOSOM, the Italian submarine command, issued the necessary orders to transfer another group of submarines to the Atlantic. This group was to cross the treacherous Strait of Gibraltar during the new moon around September 2nd. The group included the MARCONI, Emo, Faà di Bruno, Giuliani, Baracca, Torelli, Tarantini, Finzi and Bagnolini.

The MARCONI, still under the command of Lieutenant Commander Giulio Chialamberto, left Naples on September 6th and reached the approach to the strait on the 11th. Having noticed the presence of British patrol units, the captain decided to cross the narrow and perilous strait underwater, eventually reaching the Atlantic side without any problems. Once in the Atlantic, the MARCONI assumed the assigned patrol position off Cape Finesterre just north of the position assigned to the Finzi, a boat under the command of Commander Alberto Dominici. The Marconi remained in the area from the 15th to the 28th. On the 19th, Captain Chialamberto sighted a small ship and proceeded to sink it. Unfortunately, it was the Spanish trawler Alm. Jose de Carranza of 330 tons, a neutral vessel used for commercial fishing. In due course, the first Atlantic mission of the MARCONI ended with its arrival in Bordeaux on September 29th.

The permanence in Bordeaux was not long; in early October Betasom was asked by B.d.U. to organize two attack groups to join German forces in the north Atlantic. The MARCONI was assigned to the Bagnolini Group along with the Bagnolini itself, the Baracca, and the Finzi. The MARCONI left base on October 27th, the last of the group. Once at sea, the boat received a discovery signal in the afternoon of December 4th from the Malaspina. Despite the immediate search, the boat failed to locate the convoy previously signaled and continued on to the assigned area. Between the 6th and 8th of November, the MARCONI was in the patrol area spanning from 20° W to 26° W and from 55°20’N to 56°20’ N. On the 8th, the radioman aboard the submarine intercepted a radio message from the British cargo ship Cornish City of 4,952 tons which had claimed having heard a violent explosion. The MARCONI sighted the merchant ship and immediately after an escort unit forced it to seek refuge into the depths. The escort unit went on with the usual lengthy hunt dropping 14 depth charges, but missing the target because the captain had been very ingenious in taking the boat down to 125 meters. At that time, British escort units did not know that Axis boats could reach such depths. Eventually, the unit in question noticed fuel, oil, and wreckage bubbling to the surface and, assuming a kill, gave up the hunt.

It is known that the Cornish City was the lead ship of convoy HX.84 that on the 5th had been attacked and dispersed by the German heavy cruiser Admiral Scheer. The commodore aboard this ship was trying to get the convoy back together when a German FW 200 attacked. One of the escort units, H.M.S. Havelock, assumed that the explosion had been caused by a torpedo and moved forward, eventually encountering the MARCONI.

On the 9th, having received a signal with the necessary instructions, the MARCONI moved on toward a position indicated by the Otaria as one of a naval formation including an aircraft carrier and a few destroyers. Instead of the formation, the MARCONI found a straggling merchant ship already damaged by a previous attack by a FW 200 of KG40 and ablaze. Past sunset, after a first failed attack, the MARCONI placed a torpedo into the side of the Swedish ship Vingaland of 2,734 tons (some sources give the displacement at only 2,720 tons). Original Italian documentation assumed that this ship was able to reach port, but this assumption, like many others, was mistaken. This Swedish ship was built in 1935 by the shipyard Eriksberg, MekaniskeVerkstads of Gothenburg and was part of convoy HX.84 from Halifax. The sinking took place in position 55°41’N, 18°24’W with a total of six casualties and 19 crewmembers later rescued.

A few days later, in the early morning of November 14th, the MARCONI sighted another merchant ship. It could have been the opportunity for another kill, but the boat had lost the use of the attack periscope since the beginning of the mission and the use of the second periscope brought part of the turret out of the water more than once. At about 2500 meters, a single torpedo was launched but failed the target and then the captain decided to give up the chase since the ship was faster than his boat. Two days later, and precisely on the 16th, the MARCONI received another signal but the severe weather conditions did not allow it to make much progress toward a fairly large convoy. On the 18th, another signal brought the boat on another chase, but there was no contact made and soon after the submarine had to return to base, reaching Bordeaux on November 28th.

After the usual period for refitting, the MARCONI was again sent to sea, this time off Oporto, Portugal. The boat left Bordeaux on January 16th, reaching the assigned area around the 21st. Here, the MARCONI waited off the estuary of the River Tago for a convoy of about 20 ships sailing up from Gibraltar and directed to England. On the 10th, aboard the submarine a considerable trail left by leaking fuel was detected. The seriousness of the problem suggested abandoning the search for the convoy, but the morning of the same day Captain Chialaberto attacked, while submerged, a merchant ship without identifying it and failing to sink it. On the 12th, the boat left the patrol area returning to Bordeaux on the 17th of February.

1941

After a long period of refitting, in May the MARCONI was assigned to a screen which included the Argo, Mocenigo, Veniero, Brin, Velella and Emo running north to south along 12°00’N. During the refitting preceding this mission, Lieutenant Commander Chialamberto had been transferred to the submarine Bagnolini and had been replaced by Lieutenant Mario Paolo Pollina. The precise date of the MARCONI’s departure from Bordeaux is not known, but took place between the19th and the 29th of May.

Lieutenant Pollina (first officer on the left) returning to base after a patrol in the Atlantic Ocean

(Photo courtesy Erminio Bagnasco and Achille Rastelli)

On the 30th, at 08:00, the crew sighted the British tanker Cairndale and proceeded to sink it with two launches of two torpedoes each. The attack took place in position 35°20’N, 8°45’W just west of the Strait of Gibraltar (170 miles from Cape Trafalgar). The position of the sinking was given by the British authorities in 35°19’N, 8°33’W with the reported loss of four crewmembers. The Cairndale was a motor tanker (oiler) of the Royal Fleet Auxiliary and had been laid down in 1938 as the Erato. Built in 1939 by the Harland & Wolff of Belfast, it had a displacement of 8,129 tons. The reaction of the escort was immediate, but despite the launch of numerous depth charges, the boat lived to tell the story. The following day, Captain Pollina sank the Portuguese steam trawler Exportador I (given by some authors as Equador Primero) of 318 tons with the deck gun. It is not known why a neutral ship would become the target of the submarine, but we could assume that it was providing some service to the British forces.

At 23:50 on the night of June5th, the MARCONI sighted a convoy in position 35°05’, 11°45W. Along with the Velella, the MARCONI began approaching the convoy hoping to be able to break through the columns, but the intervention of one of the escorts forced it to withdraw. The attack was resumed in the early hours of the 6th, and at 04:22 the MARCONI launched two torpedoes against a large tanker described as type “Daghestan”. This was a tanker built in 1921 by the Short Bros. Ltd of Sunderland, displacing 5,842 tons and sunk by U 57 in 1940. According to the report presented by the MARCONI, one more ship was also damaged.

Two other torpedoes hit the British freighter Baron Lovat of 3,395 tons, sinking it, and one of the last weapons launched hit the Swedish cargo Taberg. The first vessel was built by Ayrshire Dockyard of Irvine in 1926 and belonged to the Hogarth Shipping Co. of Glasgow. The position of the sinking was given as 35°30N, 11°30’W and all 35 crewmembers were rescued. The Baron Lovat was carrying 3,245 tons of coke. Of the Taberg we have very limited information if only that it displaced 1,392 tons and was in ballast and thay only 6 out of the 22 crewmembers were later saved by a British ship.

The Baron Lovat and Taberg were part of convoy OG.63 from Liverpool to Gibraltar. The convoy had left Great Britain on May 25th with a total of 39 ships, later arriving in Gibraltar on June 7th after having lost 3 vessels. The British reports would indicate that in addition to the two ships sunk by the MARCONI, a third one (Glen Head), was sunk by an aircraft. During this operation, both the Velella and Emo conducted similar attacks but failed to score any success. Immediately after the audacious attack, the boat became the object of the attentions of the escort unit, and after the first few cannon shots, the captain took the boat underwater where it remained until the afternoon. The same night, having exhausted all the torpedoes, the MARCONI began the journey back to base.

After the usual refitting, the MARCONI was again assigned to a patrol, this time along with the Finzi, and again in the area just off the Strait of Gibraltar. The submarine left Bordeaux on the 3rd of August reaching the assigned area about 200 miles from the strait a few days later. On the 11th at 03:45 AM in position 37°32N, 10°20’W, the MARCONI attacked a small formation which included the corvette H.M.S. Convolvulus (K45) of the Flower class and the sloop H.M.S. Deptford (L53) of the Grimsby Class, launching two torpedoes against the latter one. Although the crew was convinced of having scored a hit, post-war records do not indicate any damage to the British units.

Meantime, it had been ascertained that a British convoy (HG.70 from Gibraltar to Great Britain) was on the move and all submarines in the area, both German and Italian, were sent on the hunt. On the 14th, the MARCONI sighted the merchant ship Sud, a Yugoslavian freighter of 2,598 tons. Having failed the attack with the torpedo, the MARCONI proceeded to finish the ship with the deck gun. Once the ship hit by many rounds came to a halt, the captain waited for the enemy crewmembers to abandon ship. Meantime, a German submarine, U 126 commanded by Korvettenkapitنn Ernst Bauer intervened, firing a few rounds into the hull of the sinking ship and claiming it as his own (he ended the war with a record of 119.110 tons sunk). All 33 crewmembers were later saved. The position of the sinking is given as 41°00’N, 17°41’W. For the record, the Sud belonged to the Oceania Brodarsko Ackionarsko Drustvo of Susak and was built in 1901 by Roger & Co. of Glasgow. Roger Jordan gives the displacement as only 2,520 tons. After the attack, the MARCONI continued chasing the convoy until the 17th and then began the return voyage to base reaching Bordeaux on August 29th. Immediately after, Lieutenant Pollina was disembarked due to health reasons and replaced by Lieutenant Commander Livio Piomarta who had already served aboard the submarine Ferraris.

Lieutenant Commander Livio Piomarta

(Photo U.S.M.M.)

On October 5th, the MARCONI was again at sea and directed to Gibraltar to intercept a convoy along with the Ferraris, Archimede, and Barbarigo. On October 22nd, the MARCONI was located 720 miles WNW of the strait. On the 25th, the Ferraris was scuttled after an aerial bombing (Catalina A of the 202 R.A.F. Squadron) and later attacked and sunk by the British destroyer H.M.S. Lamerton. On the 26th, the Ferraris made contact with the convoy. On the 28th, the MARCONI sighted many flares and, at 23:30, following a request from Betasom, it communicated its position (42°55’N, 21°55W).

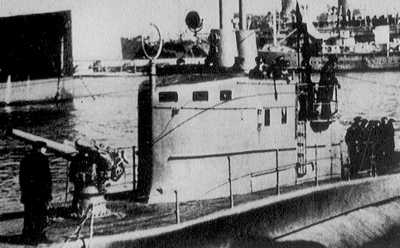

The Marconi in Bordeaux in July 1941 after an extensive refitting which included the redesign of the conning tower

(Photo courtesy Erminio Bagnasco and Achille Rastelli)

A German submarine, also in the area, indicated that at that point the MARCONI was about 30 miles south of the convoy. The same day, U-432 sank the British cargo Ulea (part of HG.75 including 17 ships, 4 of which were lost) at 05:09 in position 41°17N, 21°40W. Assuming that the positions given are accurate, the MARCONI was almost 100 miles from the position where the Ulea was lost. Furthermore, the MARCONI was north, not south of the convoy. In any event, this was the last time the whereabouts of the MARCONI were known. The submarine failed to return to base and was declared lost west of Gibraltar between October 28th and December 4th (the last date being the maximum endurance at sea).

Additional notes

Erminio Bagnasco and Achille Rastelli wrote in “Sommergibili in Guerra”: “[the Marconi] would be lost under the command of Liutenant Commander Livio Piomarta, probably sunk by mistake by the German submarine U.67 on October 28th, 1941 during an attack against a convoy off Portugal.” But suggestion that the submarine Marconi was sunk by the German U-boat U67 in 1941 has proved incorrect as the German boat was not at sea at the time of the Marconi’s disappearance