Foca was a minelaying submarine of the eponymous class, type Cavallini (displacement 1,333.04 tons on the surface, 1,659.44 submerged). Foca was the class leader of the first class of minelaying submarines of the Regia Marina which finally managed to combine excellent performance (unlike the previous X 2 and Bragadin classes) and not exorbitant costs (unlike the previous Pietro Micca).

The boat completed only three war missions covering a total of 2,063 miles on the surface and 293 miles submerged for a total of 13 days of navigation.

Brief and Partial Chronology

January 15th, 1936

Setting upstarted at the Franco Tosi shipyards in Taranto.

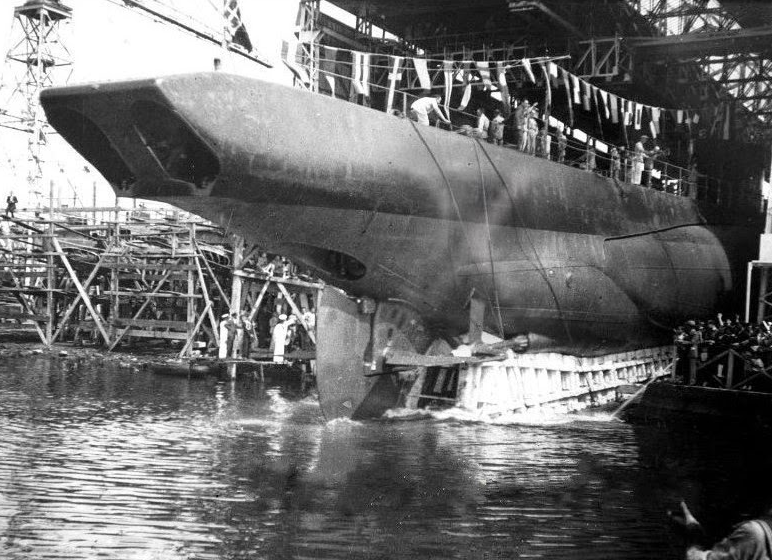

June 27th, 1937

The Foca was launched at the Franco Tosi shipyard in Taranto. The godmother of the boat was the wife of a foreman of the Arsenal of Taranto, decorated with a star of merit for work.

The launch of Foca in Taranto

November 6th, 1937

Foca officially entered active service. Together with the twin boats Atropo and Zoea, Foca was assigned to the XLV Submarine Squadron (Taranto Submarine Group), which also included the other minelaying submarines of the Regia Marina (Pietro Micca, Marcantonio Bragadin, Filippo Corridoni, X 2 and X 3).

Among its first commanders was Lieutenant Gino Birindelli, future Gold Medal for Military Valor. In peacetime, it carried out intensive training and mine-laying exercises with inactive ordnance.

Summer 1939

The XLV Squadron becomes, following the establishment of the Submarine Squadron Command, the XLVIII Submarine Squadron. Subsequently, Foca, together with Pietro Micca, was assigned to the XV Submarine Squadron (later XVI Squadron) of the I Grupsom, based in La Spezia.

Early 1940s

Commander Vittorio Meneghini took command of the Foca.

Spring 1940

Commander Meneghini was transferred to the larger submarine Pietro Micca and was replaced in command of the Foca by Lieutenant Commander Mario Ciliberto. (According to another source, Ciliberto assumed command of the Foca from February 16th, 1939).

Foca near Taranto in 1940

(From “Sommergibili in guerra” by Achille Rastelli & Erminio Bagnasco)

June 10th, 1940

Upon Italy’s entry into the war, Foca (Lieutenant Commander Mario Ciliberto) formed together with Micca the XVI Squadron of the I Submarine Group, based in La Spezia.

June 13th, 1940

According to some sources, on this date the Foca was laying mines, standing on the surface, off Alexandria, when it was attacked by the British destroyers H.M.S. Decoy and H.M.S. Voyager (on an anti-submarine search mission together with two other destroyers, H.M.S. Stuart and H.M.S. Vampire), which forced it to dive, after which H.M.S. Voyager (Commander Morrow) subjected it to bombardment with depth charges, but without being able to damage it.

However, Foca’s first mission would appear to have taken place on August 27th, 1940; the submarine object of the attack by H.M.S. Decoy and H.M.S. Voyager was Micca, which was sent to lay 40 mines the night of June 12th and which then remained lurking nearby, detecting considerable anti-submarine activity.

August 27th, 1940

Foca left Taranto under the command of Lieutenant Commander Ciliberto for a mission to transport supplies (weapons, fuel and provisions) to the base of Portolago, on the island of Leros (Italian Dodecanese).

September 10th, 1940

The boat departs from Leros at 11.50 PM to return to Taranto, with a new load of materials and ammunition placed in the mine holds.

September 11th, 1940

Foca made a crash dive at 5.45 AM and traveled at a depth of 40 meters until 6.55 PM. When it resurfaced and continued on the surface (with sea and wind force 3 from the southwest) towards the Cerigo channel, exchanging air and recharging the batteries.

September 12th, 1940

It crosses the Cerigo channel at five o’clock and dove with a crash dive at 5.40 AM, proceeding submerged at 40 meters until 7 PM, when it resurfaces to recharge the batteries, change the air and continue with the diesel engines on the surface (sea and wind were force 4 from the west).

September 13th, 1940

At 2.45 AM it steered to change course and at 6 AM it dove with another crash dive to 30 meters, and then continues submerged until 1 PM, when, having arrived outside the areas where hidden navigation was a must, it resurfaces and continues on the surface (sea and wind were force 4 from the northwest), again changing air and recharging the batteries.

September 14th, 1940

It dove at 5.40 AM, descending to 30 meters, at which depth it continues until 7 PM, when it emerged and headed slowly towards the landing of Santa Maria di Leuca (Puglie).

September 15th, 1940

Foca arrived at point A in Santa Maria di Leuca at 5.30 AM, when he was sent a telegram from the traffic light about meeting Italian ships. It then follows the coastal routes and at 6.20 AM headed for Taranto. After meeting the trawlers Perseo and Orata at 9 AM, Foca arrived at 12.55 PM at point “A” in San Vito, where it was recognized by the pilot ship before entering the Mar Grande. At 1:36 PM, the boat moored at the submarine quay in Mar Piccolo.

The Disappearance

At sunset on October 1st, 1940,Foca left Taranto under the command of Lieutenant Commander Mario Ciliberto, for a mine-laying mission off the important port and naval base of Haifa, British Palestine, built in 1933 and used by the Royal Navy (Palestine was under British mandate, like much of the Middle East, and goods from the Middle Eastern territories under British control all converged towards Haifa). It was supposed to be Foca’s third war mission.

One of the crewmembers, the second chief gunner Antonio Diana, who had enlisted in the Navy eleven years earlier, had just said goodbye to his young wife Angela, whom he had married a year before, after having given her his last paycheck, except twenty cents for the newspaper, and her wedding ring, which he intended to give to St. Anthony as a thanks on his return from the mission. He was calm, confident both in the protection of St. Anthony and in the power of the Italian diving fleet, the largest in the world. Another career soldier, the sailor electrician first class Gualtiero Vannucci, had been on board the Foca since November 30th, 1938, and considered it “his” submarine.

The next day, having passed Crotone, the submarine rounded Cape Colonne and set course for Alexandria in Egypt, to reach the point predetermined by the Submarine Command (Maricosom), i.e. 33°30′ N and 30°00′ E, one hundred miles north of Alexandria, from where it would continue on an easterly course towards the bay of Haifa.

On the basis of Operation Order No. 102 – received from Rome on September 28th – Foca was to arrive at the assigned point (32°49’36” N and 34°49’51” E) on October 13th or 14th, approaching the assigned area around dawn, and was to lay 20 mines model TV 200/800 (produced by Officine Franco Tosi, each weighing one ton and loaded with 200 kg of molten TNT) starting from the point 6 miles by 267° from the lighthouse of Cape Carmel (Palestine) and then proceeding along the 350° direction. A first row of six mines was to be laid with an interval of 50 meters between each device, then the submarine was to leave an empty space of 500 meters before laying the second and third group of mines, respectively of six and eight mines, also spaced 500 meters apart and with the mines each 50 meters from each other. The mines were to be placed at a depth of four meters, on a seabed a hundred meters deep.

32°49’36” N – 34°49’51” E

In addition to the 20 mines destined for the Haifa barrage (and placed in the mine holds), Foca carried another 16 unarmed mines in the horizontal torpedo tubes – thus finding itself with a full load of ordnance – with which it was supposed to carry out tests (laying of “experimental” control barrages, to be carried out within 48 hours from the end of the mission in a sector designated by the IV Submarine Group in agreement with Marina Taranto and to verify the behavior of the triggers when the ordnance was placed in the horizontal tubes) during the return navigation, which would have taken place along the same routes as the outward journey. It was also envisaged, as a secondary objective, the possibility of attacking enemy ships that were spotted during navigation.

The large mine holds of Foca seeing from stern

Between there and back, the boat would have had to travel over 2,000 miles (at night on the surface, during the day submerged; the last stretch entirely submerged and with electric motors, so as not to be spotted by British reconnaissance planes that would have thwarted the mission). Throughout the journey, Foca was supposed to maintain total radio silence. The mission had been timed to coincide with the full moon (which would occur on the night of October15th-16th), so as to make it easier for the Foca to spot any threats during the night.

At the same time as Foca, according to the same order of operation, her sister ship Zoea also took to the sea, with the task of laying a minefield off the coast of Jaffa (now Tel Aviv).

On October 14th, the Commander-in-Chief of the Submarine Squadron informed Benghazi that on October 17th Foca was to pass, coming from the east and heading northwest, about fifteen miles northeast of Ras el Tin. The return to Taranto was scheduled for October 23rd, preceded by the Zoea by one day. But Foca never passed off Ras el Tin, nor did it arrive at Taranto on the scheduled date or later.

On November 22nd, 1940, Maricosom reported to the command of the IV Submarine Group of Taranto that another submarine, Brin, believed it had sighted the Foca outside the obstructions of the Taranto base, but unfortunately it must have been a mistake.

On June 5th, 1941, the General Directorate of Personnel and Military Services of the Ministry of the Navy contacted the Italian Red Cross and claimed that diplomatic representatives of two unspecified neutral states had verbally stated that Foca had been captured with all its crew, and that the enemy had kept quiet about the news. In urging the CRI (Italian Red Cross) to investigate the matter, the Ministry of the Navy attached the list of the crew of the Foca. But the “rumors” of the “diplomatic representatives” were unfounded.

Nothing more was heard of Foca and the 69 men of his crew. October 23rd, 1940, the date of their failure to return to base, was given as the presumed date of death of the crew members. The next day, the wife of second-in-command Mario Della Cananea, Angelina Liuzzi – the two had only been married for nine months – gave birth to the couple’s son, Franco.

Out of 26 Italian submarines lost in the Mediterranean with no survivors, Foca, together with the smaller Smeraldo, remains one of only two boats for which not even the post-war analysis of the Allied archives has led to the identification of a plausible cause for their sinking. No British ship or aircraft claimed the sinking or damage of an enemy submarine at a place and date consistent with those of the Foca’s disappearance.

It can only be assumed that the Foca was the victim of the same devices for which he was born: mines. It seems likely that this took place between October 12th and 15th, 1940 (possibly October 13th).

Whether the submarine jumped on a British defensive barrage (which, however, according to some British sources, would not have been present in the waters of Haifa at the time), or was the victim of the accidental detonation of one of its mines during the laying (as similar accidents, although without serious consequences, occurred to the twin boats Atropos and Zoea could lead one to suspect it) is unfortunately not known.

After the loss of the Foca and the accidents that occurred at Atropos and Zoea, the poor efficiency and high danger of the submarine mine models in use were noted, and it was decided to abandon underwater covert mining. Atropos and Zoea were used as transport submarines for the remainder of the war.

Commander Ciliberto left behind his young wife Maria, whom he had married in June 1940, a few days before leaving for war. He was awarded the Silver Medal of Military Valor in Memory, with the following motivation: “Commander of minelaying submarines, he carried out the laying of three barrages in particularly dangerous waters guarded by the enemy, he demonstrated high qualities of tenacity and courage. In the fulfilment of his duty, he disappeared at sea, sacrificing, with extreme dedication, his existence to his homeland.”

Lieutenant Commander Mario Ciliberto

In the 70s Crotone named a nautical technical institute in memory of Commander Ciliberto, and in 2001 also a square in the city (Piazza Mario Ciliberto).

In August 2016, Belgian diver Jean-Pierre Misson announced that he had “found” the wreck of the Foca in the waters of Ras el Hilal, on the Libyan coast, “identifying” the wreckage from a sonar image he obtained in 2012. The news, very inopportunely, was picked up and spread by some local media, in particular the newspapers “Il Crotonese” and “La provincia crotonese” (Crotone being the city of the last commander of the Foca, Mario Ciliberto) and even on the otherwise excellent website www.sommergibilefoca.it (where anyone is free to look at the photos of the sonar scans, provided by Misson himself: it is quite evident – except, apparently, to the authors of the site – how forced and far-fetched are the “correlations” invented by Misson to look for correspondences between the historical photos of the Foca and the sonar scans of his imaginary “wreck”. Never as in this case, unfortunately, is the saying that “the eyes only see what the mind wants to see” valid).

On the reliability of Jean-Pierre Misson’s statements, we limit ourselves to reporting the following, leaving it to the reader to decide.

Over the last few years, Misson claimed to have found in two very small bodies of water (a few square kilometers), off the coast of Tabarka (Tunisia) and Ras el Hilal (Libya), no less than ten submarines (the British Urge and the Italians Argonauta, Foca, Dessiè, Asteria, Avorio, Porphyry and Cobalt, as well as others to which, thank God, he did not “succeed” in putting a name on it), the British destroyer H.M.S. Quentin, the Italian tanker Picci Fassio, the German motor torpedo boat S 35 and probably other wrecks, a few hundred meters away from each other (which would already be, in itself, almost improbable). See, in this regard, the heated discussions on the AIDMEN forum as well as Misson’s claims that in some cases, through journalists completely inexperienced in the subject, have unfortunately reached the newspapers (this is the case, in addition to Foca, also of the British Urge). All the “finds”, with a methodology completely unacceptable for any serious search for a wreck, took place through the “interpretation” of very vague shadows recorded by sonar, without a single dive on the imaginary wrecks in question.

Most of the above-mentioned vessels, unlike the Foca, had survivors among their crews, and both these survivors and the units responsible for the sinkings recorded, at the time, the positions of these sinkings. From this it appears with certainty that all the submarines and ships mentioned above sank in places tens if not hundreds of miles distant from those where Misson claims to have found them; but this does not discourage Misson from claiming that all those who recorded such positions were grossly wrong in their surveys by several tens of miles (quite impossible, especially when we are talking about almost fifteen different units), while he does not remotely take into consideration that he may have been wrong in identifying the sonar images of the “wrecks” in question.

These sonar images, in reality, appear to any impartial observer as nothing more than vague and indistinguishable gouges, not identifiable in any way and which in all probability do not show any wreck, or other man-made object; it is Misson who “sees” the wreckage, turning every shadow detected by his sonar into a “submarine”. Exemplary, in this regard, is the procedure of “identification” of the “wreck” of H.M.S. Urge, even announced in the newspapers: in support of his thesis, Misson contacted a sonar image expert to identify the vague sonar image he attributed to the wreck of H.M.S. Urge, but the latter, having viewed the image, denied the possibility of identifying it.

This did not slow down Misson in the slightest, who reaffirmed his self-referential identification of the Urge, and then took care not to ask for other expert opinions (which could only have been negative, since there was no wreckage) for subsequent “identifications”. Even more grotesque is the attribution of the causes of the sinking of these units: if ignoring the fact that they are known with certainty for all the ships and submarines indicated (except Foca and perhaps Argonauta), Misson attributes a large part of the sinkings of the “submarines” of Tabarka to a phantom minefield present in those waters.

In fact, it is known with certainty that there was no minefield at Tabarka except one that was laid only after almost all the sinkings mentioned, and therefore cannot be the cause. Again, that doesn’t seem to bother Misson in the slightest. For the units for which he could not invent an impossible sinking on non-existent mines, Misson claimed that they (including submarines, indeed, first) drifted for tens of miles before sinking, conveniently, all in the patch of sea inspected by his sonar, although it is clear from the reports of the time that these units sank at the sites of the attacks, without drifting.

All this is trusted to say a lot about the validity of Jean-Pierre Misson’s “discoveries”. The news of the discovery of the Foca near Ras el Hilal is unfortunately to be considered as completely unfounded.

Original Italian text by Lorenzo Colombo adapted and translated by Cristiano D’Adamo

Operational Records

| Type | Patrols (Med.) | Patrols (Other) | NM Surface | NM Sub. | Days at Sea | NM/Day | Average Speed |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Submarine – Medium Range | 3 | 2,063 | 293 | 13 | 181.23 | 7.55 |

Crew Members Lost

| Last Name | First Name | Rank | Italian Rank | Date |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Abaini | Franco | Naval Rating | Comune | 10/12/1940 |

| Argellati | Luigi | Naval Rating | Comune | 10/12/1940 |

| Battistoli | Augusto | Naval Rating | Comune | 10/12/1940 |

| Bianchi | Ferruccio | Chief 2nd Class | Capo di 2a Classe | 10/12/1940 |

| Bottigni | Giovanni | Naval Rating | Comune | 10/12/1940 |

| Brunetti | Felice | Naval Rating | Comune | 10/12/1940 |

| Calamini | Mario | Chief 2nd Class | Capo di 2a Classe | 10/12/1940 |

| Capovilla | Federico | Naval Rating | Comune | 10/12/1940 |

| Cerreto | Pellegrino | Naval Rating | Comune | 10/12/1940 |

| Cheli | Antonio | Naval Rating | Comune | 10/12/1940 |

| Ciliberto | Mario | Lieutenant Commander | Capitano di Corvetta | 10/12/1940 |

| Consiglieri | Alfredo | Naval Rating | Comune | 10/12/1940 |

| Coppi | Oronzo | Chief 2nd Class | Capo di 2a Classe | 10/12/1940 |

| Corazza | Walter | Naval Rating | Comune | 10/12/1940 |

| Coridi | Bruno | Chief 2nd Class | Capo di 2a Classe | 10/12/1940 |

| Cozzolino | Alfredo | Naval Rating | Comune | 10/12/1940 |

| D’adelfio | Giuseppe | Naval Rating | Comune | 10/12/1940 |

| Della Cananea | Mario | Lieutenant | Tenente di Vascello | 10/12/1940 |

| Diana | Antonio | Chief 2nd Class | Capo di 2a Classe | 10/12/1940 |

| Digosciu | Tommaso | Chief 1st Class | Capo di 1a Classe | 10/12/1940 |

| Doglio | Riccardo | Junior Chief | Sottocapo | 10/12/1940 |

| Dogliotti | Livio | Junior Chief | Sottocapo | 10/12/1940 |

| Dringoli | Angelo | Naval Rating | Comune | 10/12/1940 |

| Emanuelli | Luigi | Lieutenant Other Branches | Capitano G.N. | 10/12/1940 |

| Favaro | Demetrio | Chief 2nd Class | Capo di 2a Classe | 10/12/1940 |

| Gennaro | Giuseppe | Naval Rating | Comune | 10/12/1940 |

| Ghirardi | Aurelio | Junior Chief | Sottocapo | 10/12/1940 |

| Girardi | Silvio | Junior Chief | Sottocapo | 10/12/1940 |

| Gori | Osvaldo | Naval Rating | Comune | 10/12/1940 |

| Grippa | Gian | Naval Rating | Comune | 10/12/1940 |

| La Spada | Ugo | Ensign | Guardiamarina | 10/12/1940 |

| Landi | Carlo | Naval Rating | Comune | 10/12/1940 |

| Landucci | Omero | Chief 1st Class | Capo di 1a Classe | 10/12/1940 |

| Magni | Egisto | Naval Rating | Comune | 10/12/1940 |

| Maioli | Paride | Naval Rating | Comune | 10/12/1940 |

| Malandrino | Giuseppe | Sergeant | Sergente | 10/12/1940 |

| Masi | Attilio | Sergeant | Sergente | 10/12/1940 |

| Natali | Fiorenzo | Sergeant | Sergente | 10/12/1940 |

| Ouvieri | Domenico | Chief 2nd Class | Capo di 2a Classe | 10/12/1940 |

| Paderni | Mario | Naval Rating | Comune | 10/12/1940 |

| Pagano | Gaetano | Naval Rating | Comune | 10/12/1940 |

| Pareto | Lino | Naval Rating | Comune | 10/12/1940 |

| Pastorelli | Ernesto | Sublieutenant | Sottotenente di Vascello | 10/12/1940 |

| Peluso | Sebastiano | Sergeant | Sergente | 10/12/1940 |

| Perduca | Galeazze | Chief 2nd Class | Capo di 2a Classe | 10/12/1940 |

| Pianeta | Francesco | Naval Rating | Comune | 10/12/1940 |

| Picazio | Gaetano | Chief 2nd Class | Capo di 2a Classe | 10/12/1940 |

| Picone | Salvatore | Naval Rating | Comune | 10/12/1940 |

| Pignati | Pietro | Naval Rating | Comune | 10/12/1940 |

| Pini | Amedeo | Chief 2nd Class | Capo di 2a Classe | 10/12/1940 |

| Pipino | Giovanni | Chief 2nd Class | Capo di 2a Classe | 10/12/1940 |

| Pisani | Renato | Sublieutenant | Sottotenente di Vascello | 10/12/1940 |

| Preziosi | Mario | Naval Rating | Comune | 10/12/1940 |

| Prisco | Giuseppe | Naval Rating | Comune | 10/12/1940 |

| Romeo | Diego | Naval Rating | Comune | 10/12/1940 |

| Rossi | Sarno | Naval Rating | Comune | 10/12/1940 |

| Rutigliano | Antonio | Naval Rating | Comune | 10/12/1940 |

| Salernitano | Carmine | Naval Rating | Comune | 10/12/1940 |

| Sassoli | Mario | Chief 2nd Class | Capo di 2a Classe | 10/12/1940 |

| Schiavone | Ciro | Naval Rating | Comune | 10/12/1940 |

| Scoccabarozzi | Severino | Junior Chief | Sottocapo | 10/12/1940 |

| Signoracci | Elio | Naval Rating | Comune | 10/12/1940 |

| Spano | Giuseppe | Junior Chief | Sottocapo | 10/12/1940 |

| Torrisi | Angelo | Naval Rating | Comune | 10/12/1940 |

| Traverso | Angelo | Naval Rating | Comune | 10/12/1940 |

| Trento | Adriano | Sublieutenant G.N. | Tenente G.N. | 10/12/1940 |

| Vannucci | Gualtiero | Naval Rating | Comune | 10/12/1940 |

| Vastola | Vincenzo | Junior Chief | Sottocapo | 10/12/1940 |

| Volpasi | Domingo | Sublieutenant G.N. | Tenente G.N. | 10/12/1940 |