Chronicle of the journey of an Italian merchant ship, which from November 1941 to January 1942, was the first to complete a non-stop journey between Japan and France, violating the Anglo-American naval blockade.

Just before Italy’s foray into World War II, 212 Italian ships for a total of 1,209,090 tons were docked in ports far away from the motherland. Many of these units, as we shall see, were even docked in enemy ports. A few days before the declaration of war against France and Great Britain, the position of the Italian merchant ships and tankers was as follows:

- Italian East Africa (Eritrea and Somalia) 33 units.

- Northern and Eastern Europe 11 units

- Spain and Spanish possessions 32 units

- Portugal and Portuguese possessions 3 units

- United States 26 units

- Central America 14 units

- Colombia and Venezuela 8 units

- Brazil 18 units

- Uruguay 2 units

- Argentina 16 units

- Iran 4 units

- Thailand 4 units

- China and Japan 5 units

- British and Commonwealth ports, 33 units

- French Atlantic ports, 3 units

The Ministry of the Navy advised all captains to bring their vessels into friendly (or believed friendly) ports, but this order, issued only five days before the declaration of war, was released with too much delay, causing one third of the merchant fleet to be lost. This was to be the first of a succession of serious disasters. Of the 212 units forced into exile or, as it happened to the ones in Great Britain, captured, the vast majority belonged to a class of fairly modern ships of large tonnage. Six of these ships were over 10,000 tons, 64 ranged from 6,000 to 10,000 tons would have been very valuable during the conflict. The loss of 136 ships between 2,000 and 6,000 tons was very serious; these units would have been very useful for the traffic between Libya and Italy. Also important was the loss of 46 tankers, units always in short supply in the Regia Marina. In 1940, at a total of 3,400,000 tons, tankers represented less than 0.4%. Beginning in July 1940, after the commencement of the hostilities, Supermarina devised a plan to attempt to move a certain number of ships located in Spain, the Canary Islands and even Brazil to the German occupied ports of France. This operation was partially successful thanks to the courage demonstrated by the Italian crews. In time, Supermarina, under pressure from high-ranking officers of the Kriegsmarine, who had developed a certain interest after having seen half a dozen Italian ships arriving in Bordeaux, designed a second and more challenging plan. The project was intended for the transfer of some of the better Italian units, some of which had already violated the British blockade, between Bordeaux and Japan with the intent to furnish the Axis powers with much needed, and rare, rough material.

Towards the end of September 1941, Supermarina in concert with the Italian attaché in Tokyo, Admiral Carlo Balsamo, selected a first group of ships adapted to the task. After some scrutiny, the selection fell to the Himalaya, Orseolo, Galitea (ex Ramb II), Fujijama, Cortellazzo and the tanker Carignano (1). These units, which were located in Asian ports under Japanese control, were selected because of their seafaring qualities and favorable technical characteristics, such as endurance, speed and cargo capacity. As part of a secret agreement between the Regia Marina and the German Seekriegsleitung, part of the cargo loaded on Italian ships in the Orient, and destined to violate the British blockade, would be given to Germany in exchange for military equipment.

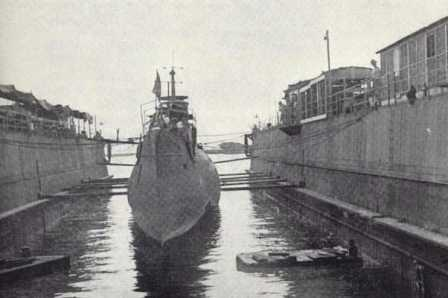

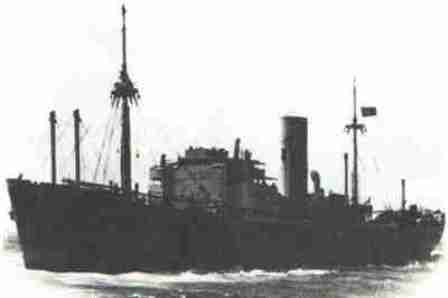

M/V Fujiama

Between the end of October and the beginning of November 1941, Supermarina gave the Italian Naval attaché in Tokyo orders to send the first ship to Bordeaux. The Cortellazzo would be taking advantage of the shorter daylight in fall, an expedient useful to protect the ship during the approach to the central Atlantic and the Gulf of Biscay. As proof of the great interest that had developed amongst the Germans for the success of the mission, of the over 6,000 tons loaded in Kobe and later in Dairen, 4,309 were destined for Germany. In the large holds of the Cortellazzo, amongst the various goods, the Japanese loaded 496 tons of tires, 159 tons of canvas, 100 tons of tin, 36 tons of copper, 61 tons of nickel, 10 tons of wolfram, 1,400 tons of vegetable oil, 285 tons of cannabis, 1,140 tons of peanuts, 285 tons of tea, and 275 tons of varnish. According to the plan, the Cortellazzo, and the other units which would have followed soon after, the Orseolo and the Fusijiana, would have followed the route of the Cape of Good Hope. Before Japan’s entry into the war, the north-south route across the Pacific, the crossing of Cape Horn, and the transit from south to north along the Atlantic were much safer than a westward route. This route allowed the Italians and the Germans alike to stay away from areas patrolled by British units.

M/V Cortellazzo’s journey

Later on, with the United States’ entry into the war, this strategy was changed and the ships were sent across the Indian Ocean, which at that time was not patrolled by enemy ships as much. Before the departure of the Cortellazzo, nine German ships loaded with rare goods had already left Japan and Korea directed to Bordeaux along the Cape Horn route. Of these ships, five had reached the Atlantic port of Bordeaux. Statistically speaking, the chances of the Cortellazzo were almost fifty-fifty. The possibility of being intercepted was so high that, just before departure, the ship was fitted with a 50 Kg. charge near the propeller shaft and destined to be exploded, thus causing the immediate sinking of the ship.

On November 6th the Cortellazzo under the command of C.L.C. Luigi Mancusi set sail from Kobe and, after a brief and uneventful three-day trip, the ship reached Dairen, in Korea. During this segment, the ship sailed under the false identity of the Japanese merchantman Dai Ichi Choyu Maru. On November 16, 1941, at 9:15 PM the Cortellazzo left the harbor of Dairen, beginning an adventurous and perilous journey. Crossing the Yellow Sea, the ship reached the Island of Quelpart where it entered the Pacific Ocean and assumed a different false identity. Exiting the Strait of Van Diemen, the Cortellazzo assumed the identity of the Japanese ship Kingfa-Maru and Japanese flags were painted along the sides while the funnel changed colors. On November 27th , while the Italian blockade-runner was between the Caroline Islands and the Marshall Islands, Mancusi spotted three Japanese oceanic submarines navigating in line and he altered course to avoid contact. On December 8th, after having left Gilbert Island to starboard and Ellice Island to port, the radio operator of the Cortellazzo intercepted signals from the American base of Pearl Harbor announcing the Japanese attack and the American declaration of war. This new event made the Italian mission even more dangerous.

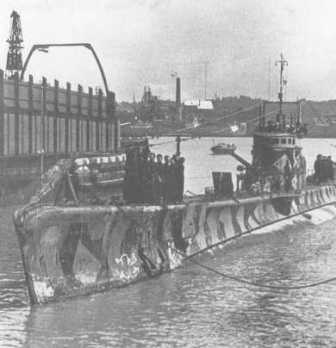

Fortunately, commander Mancusi, the right man for the job, without waiting for orders from Supermarina immediately changed the ship’s camouflage (keeping the Japanese colors would have meant disaster). The evening of December 8th, Mancusi informed Navitalia-Tokyo, Betasom (the Italian base in Bordeaux), Maricolleg-Berlin and Navitalia-Berlino of the possibility of transforming the Cortellazzo into the neutral Swedish ship Delhi. For two days, Mancusi’s sailors wiped out the Japanese flags and signs and repainted the funnel. On the 10th, the Cortellazzo displayed her new coat and a new false identity. The funnel was painted yellow to represent the shipping company “Svenska Ostasiasche Kampt.Det.” with a large light blue circle with the three crowns of the Swedish Royal house, while the broadsides had two Scandinavian flags and the name Delhi – Sweden.

M/V Himalaya

Thanks to this masquerade, the Italian ship was able to continue on this route past the Samoa Islands and crossing the dangerous waters between the Tuamotu Islands (under the control of French forces in Papeete loyal to De Gaulle). After passing the Tuamotu, the Cortellazzo-Delhi continued on a south-south-west course, reaching the troubled waters of Cape Horn. On December 24th, in the middle of a violent storm, Mancusi confirmed his fame as a talented sailor and, after a titanic fight, was able to cross the perilous cape, reaching the waters of the Atlantic Ocean. After navigating east of the Falkland Island and west of Austral Georgia, the Italian vessel pointed north, keeping itself safely in the middle of the Atlantic. Passing the strait of Natal and Freetown, the narrowest point between the African and American continents, the Cortellazzo navigated along the Brazilian coast near the Island of Fernando de Noronha and the smaller island of San Paolo, reaching on the 10th of January the Atlantic area most patrolled by the Anglo-American naval forces. It was at this point that, following orders received from the Kriegsmarine, Captain Mancusi turned est and reached Spanish territorial waters. This maneuver was fully successful despite the fact that on the 16th the course was changed after the sighting of a large British tanker.

M/V Orseolo

Passing Cape Ortegal, the Corterlazzo moved on a course parallel to the northern Iberian coast to avoid detection by the long-range flying boat Sunderland and the British submarines patrolling the Gulf of Biscay in the hunt for the U-Boots. On the 25th, the Cortellazzo crossed Cape Higuer where it met four German minesweepers which had sailed from Bordeaux and were going to protect the ship and its precious cargo against British attacks. On January 27th, after having navigated 21,163 miles in 1,730 hours at an average speed of 12.23 knots, the Italian merchantmen entered the river Girond and docked at 12:23 at the Le Verdun dock. After the habitual and much deserved celebrations attended by high ranking German Naval officers, representatives of the Regia Marina honored Captain Mancusi and the Chief engineer with a Silver Medal, while all other officers received the Bronze Medal and the crew the “croce di guerra”. The precious cargo transported by the Cortellazzo was immediately sent to Germany and Italy. On the 29th of January, the Cortellazzo, after having received some alterations similar to the other units designated for the traffic with Japan, was transferred to the command of C.L.C. Augusto Paladini with the order to transfer 6,000 tons of goods to Japan. Amongst the cargo was mercury, special steel, minerals, war material (airplane engines, submarine equipment, special weapons) and medicine. The ship would return to Bordeaux with a similar cargo of goods hard to find in Europe and much needed by the Axis war industry. Unfortunately, this time the Italian ship was not so lucky.

In addition to the Italian crew, the ship embarked seven German officers, petty officers and sailors destined to reach Kobe. The ship left the Girond the evening of November 29th and was escorted to Cape Finestrerre by the German torpedo boats Kondar, Falke and T22. Immediately after the departure of the escort, the ship was sighted by a British Suderland which led a destroyer squadron to the easy prey. The morning of December 1st, after only two days of navigation, the Cortellazzo was attacked by the destroyer Reboudt and other light units. Realizing that fighting was out of the question (the ship did not have armament), Captain Paladini ordered the scuttling of the ship by arming the prearranged mine. In a few minutes, at around 8:00 AM in a position 44’ north, 20′ west the Cortellazzo disappeared into the water.

Notes:

The 7th of July a large group of technicians, workers and specialists of the Regia Marina left La Spezia bound for Bordeaux to begin modifying and arming the ships Himalaya, Cortellazzo, Orseolo e Fusijama. This work was ordered by Rome with the intent to provide these ships with adequate protection during their missions to Japan. Unfortunately, due to lack of equipment and time, only the Orseolo was completely adapted to the new use. The armament to be installed on the Italian ships (based on directives from the German command in Bordeaux) would have included a 105mm gun (1) to be used against naval or aerial attacks, two German 20mm antiaircraft machine guns, two French 9mm machine guns, and two smoke-laying apparatuses.

(1) Or an older 75″ mm one captured from the Polish

Translated from Italian by Cristiano D’Adamo