Turchese was a coastal submarine of the Perla class with a displacement of 680 tons on the surface and 844 submerged.

During the conflict against the Allies (June 10th, 1940, through September 8th, 1943) the boat carried out 32 patrols (mostly in the Strait of Sicily and along the North African coast) and 26 transfer missions, covering 27,904 miles on the surface and 5255 submerged, as well as 95 outings for training or sea trials. It was thus the second Italian submarine for the number of missions carried out in the 1940-1943 conflict, surpassed only by the old H 2 which, however, was used for “second line” tasks in much less dangerous waters.

Seriously damaged by a British aircraft in an episode of “friendly fire” in the aftermath of the armistice, it was never repaired, remaining unused until the end of the war and was subsequent demolition under the conditions of the peace treaty.

Brief and partial chronology

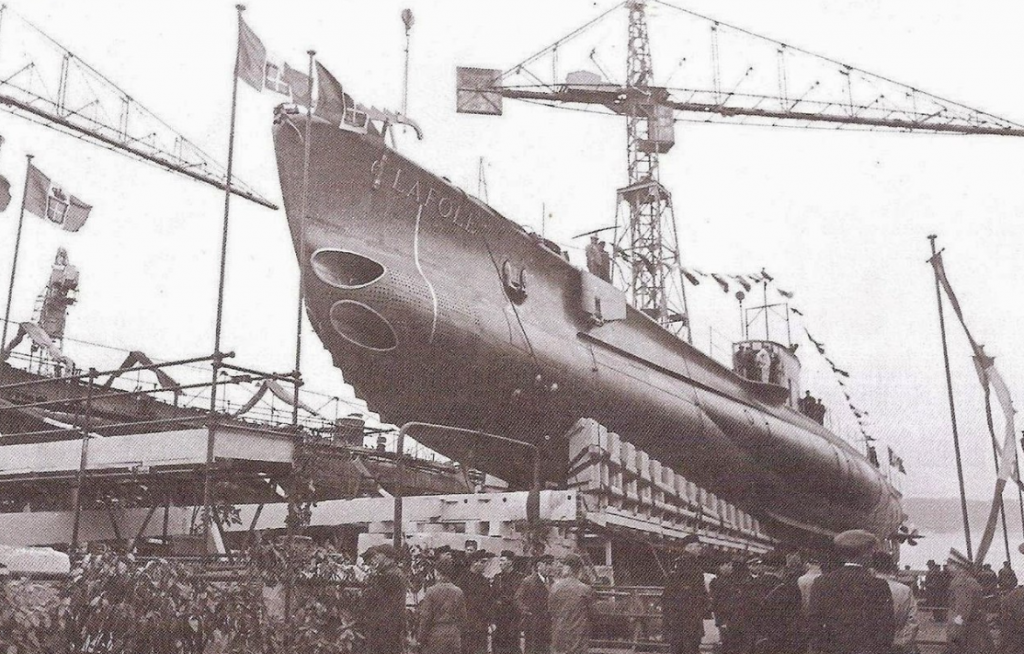

September 27th or 28th, or 29th, 1935

Setting up at the “Cantieri Riuniti dell’Adriatico” (C.R.D.A.) in Monfalcone (construction number 1143).

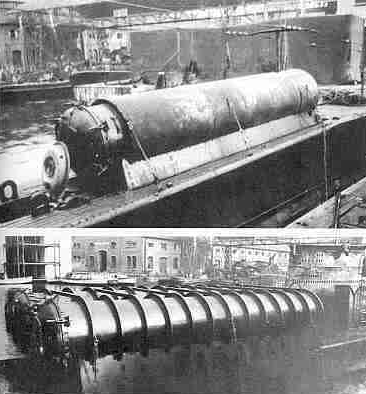

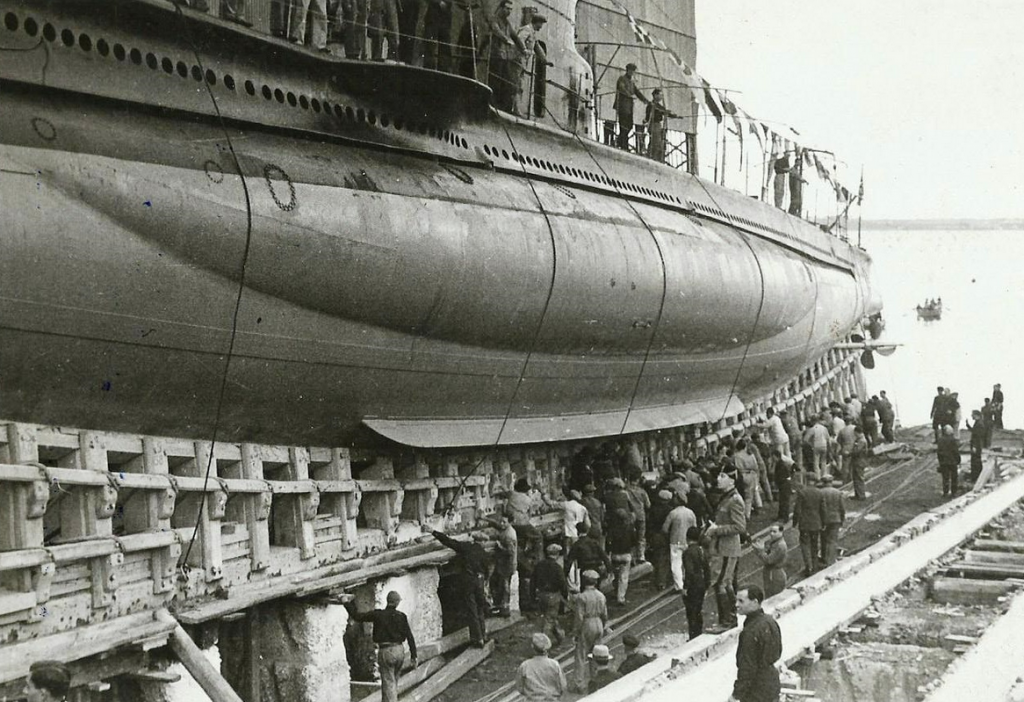

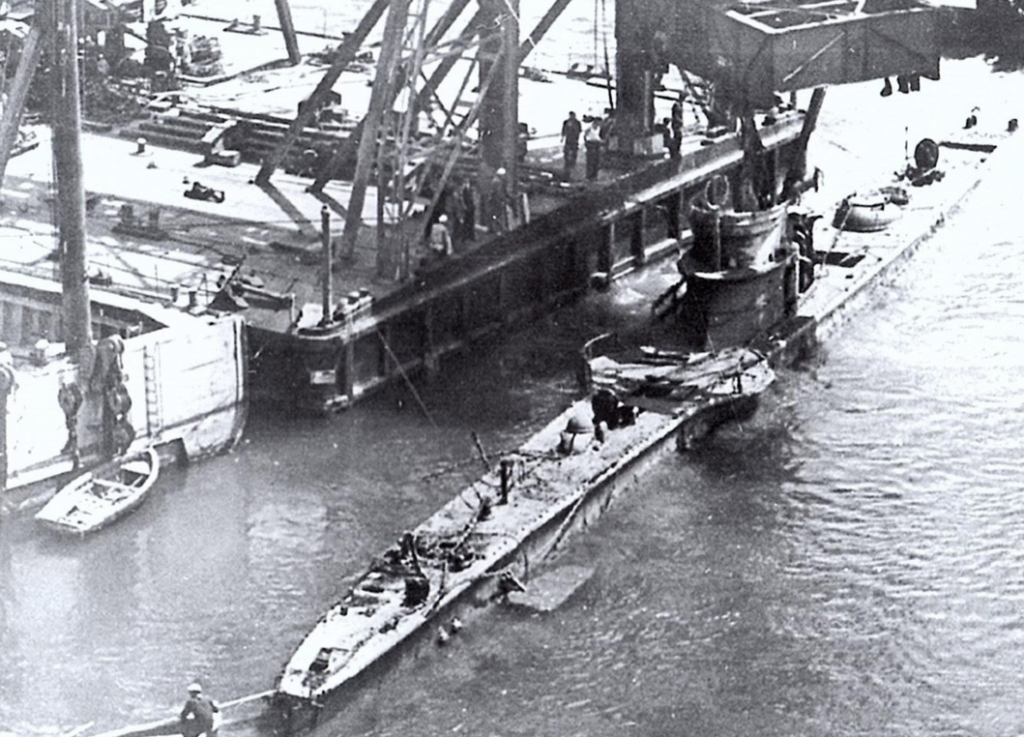

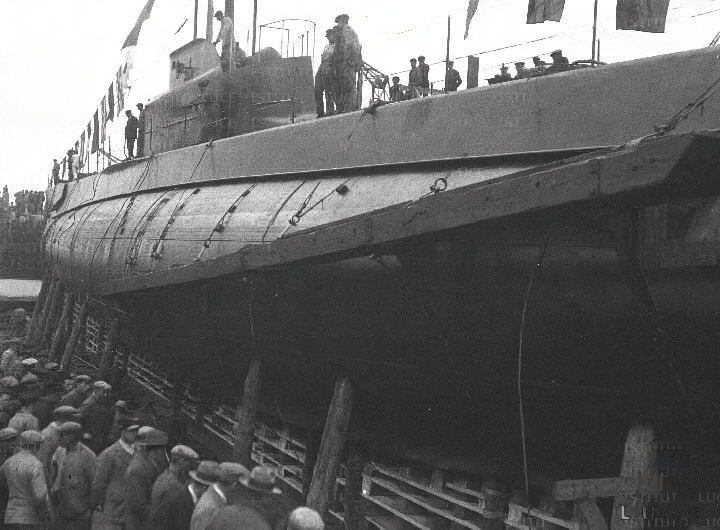

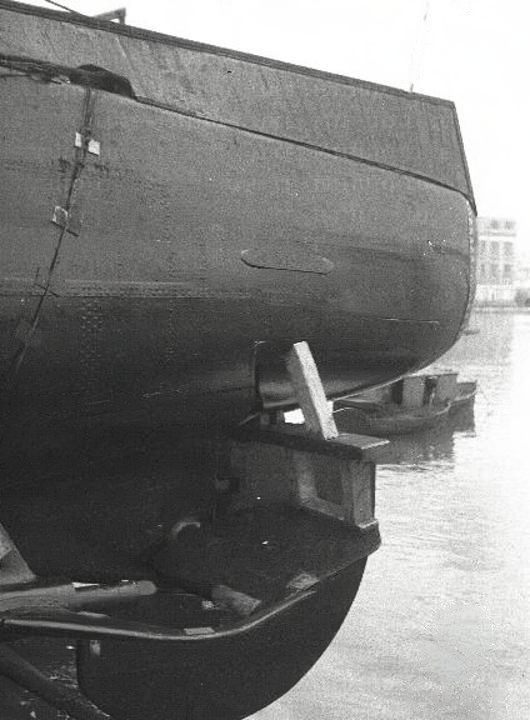

Turchese under construction. Note the joining of the sheet metal using large rivets.

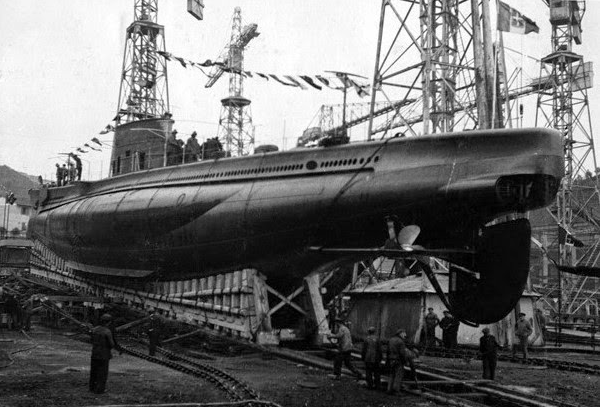

July 19th, 1936

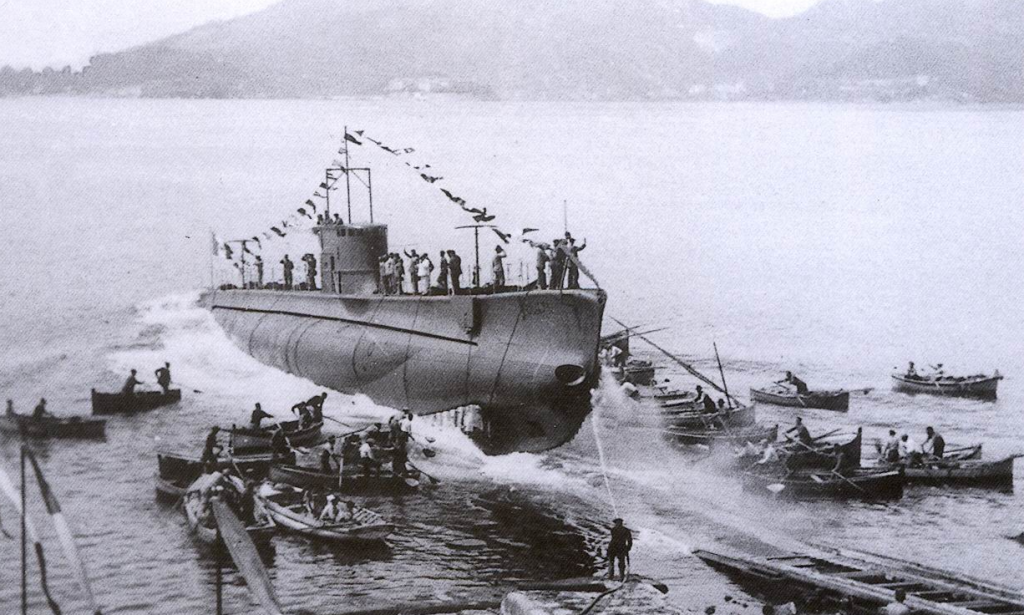

Launched at the C.R.D.A. in Monfalcone.

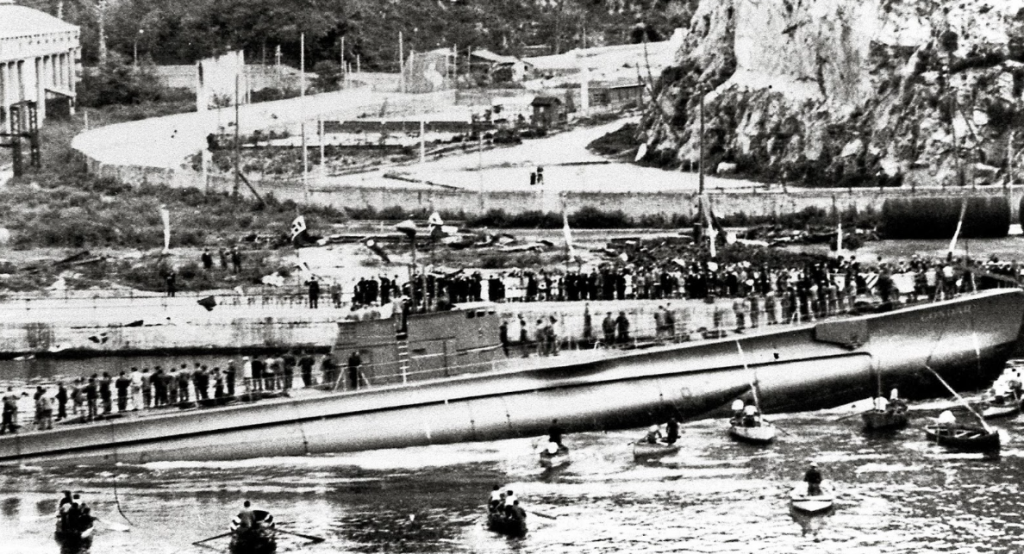

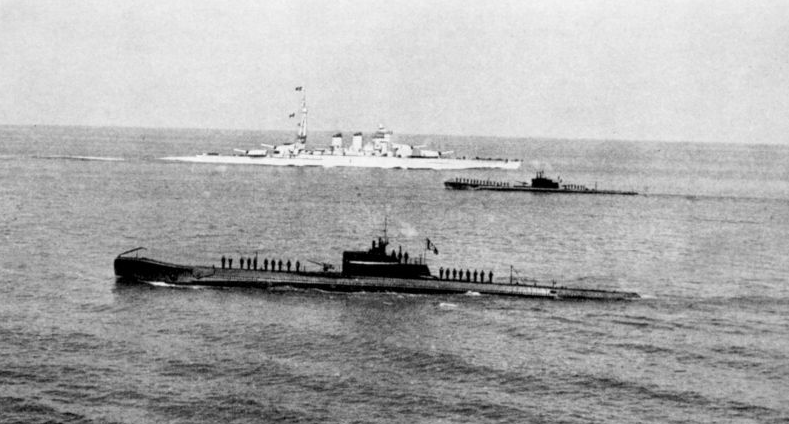

Turchese in Monfalcone after its launch

(Museo della Cantieristica di Monfalcone)

September 21st, 1936

Entry into service.

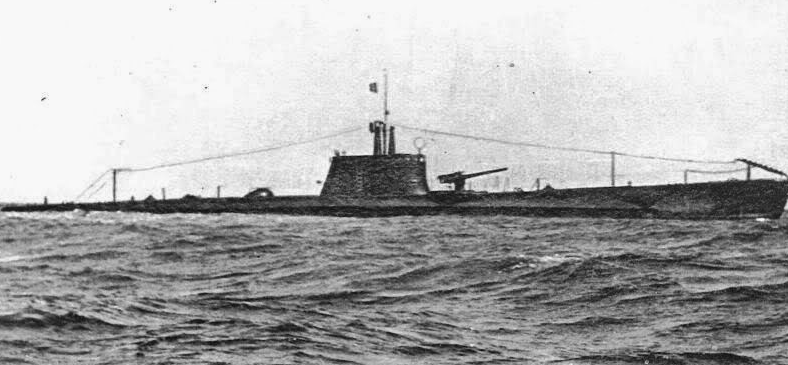

October 15, 1936

Turchese was placed under Maricosom (the Submarine Squadron Command) and assigned to the XXXV Submarine Squadron, based in Messina (for another source, to the XXXIV Squadron of the III Grupsom, also based in Messina).

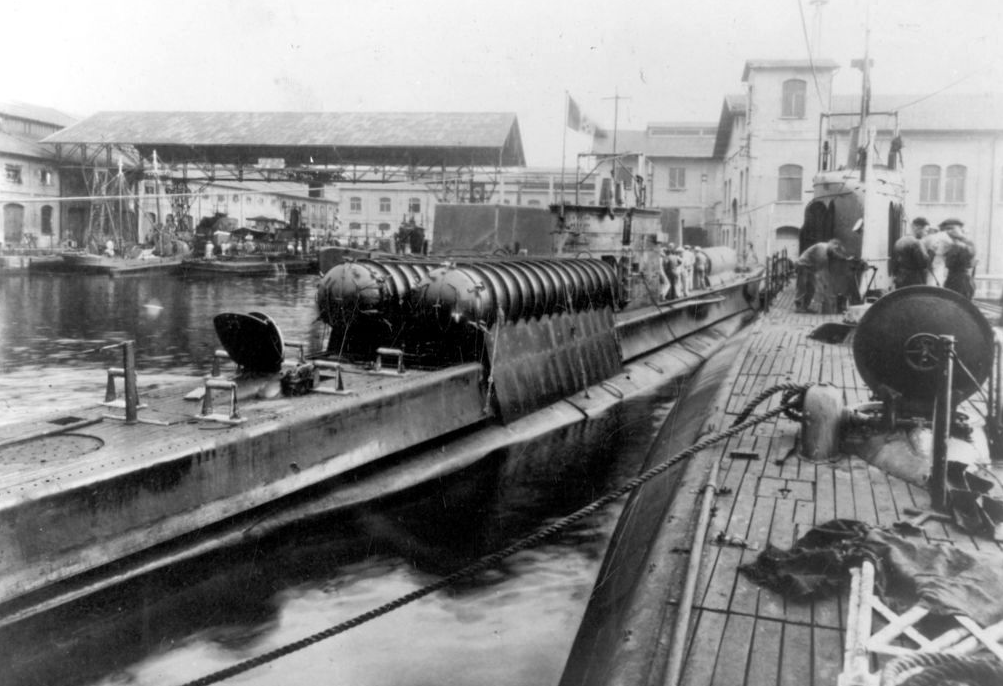

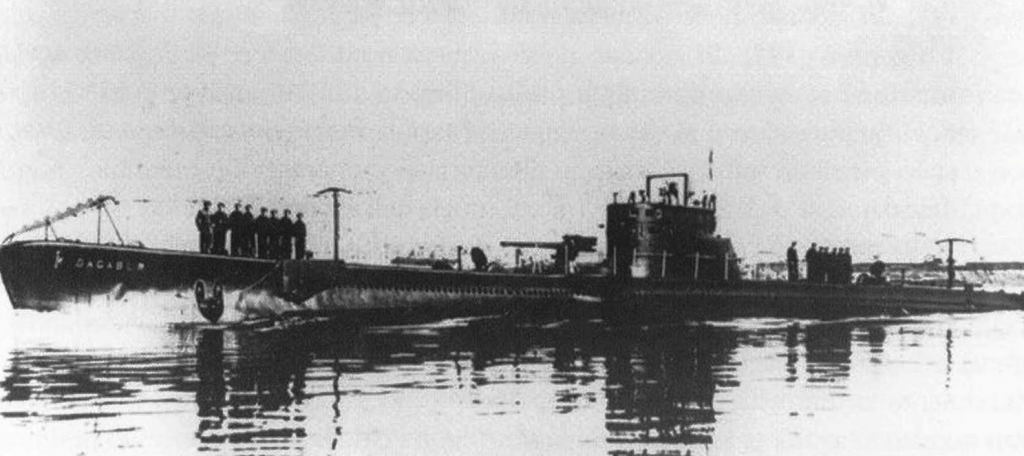

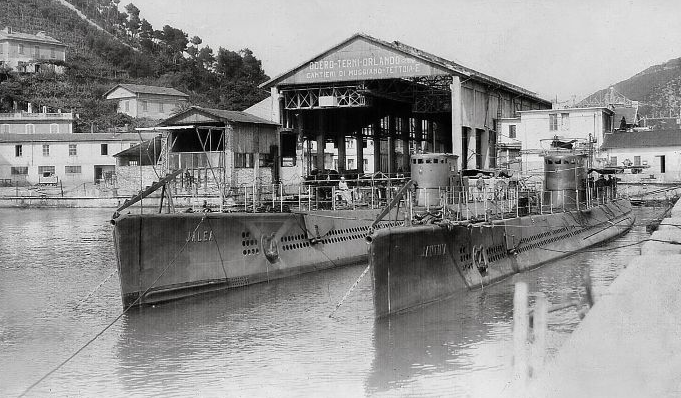

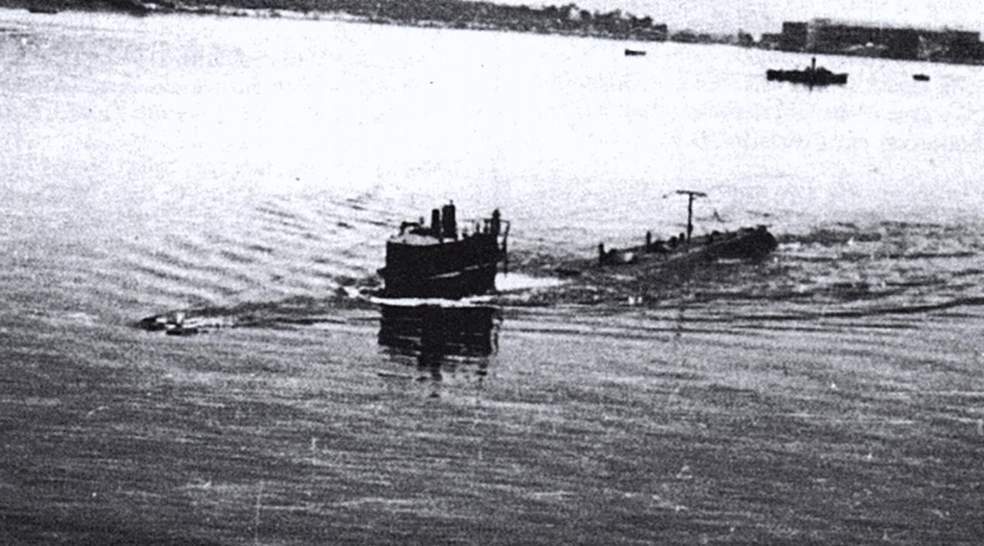

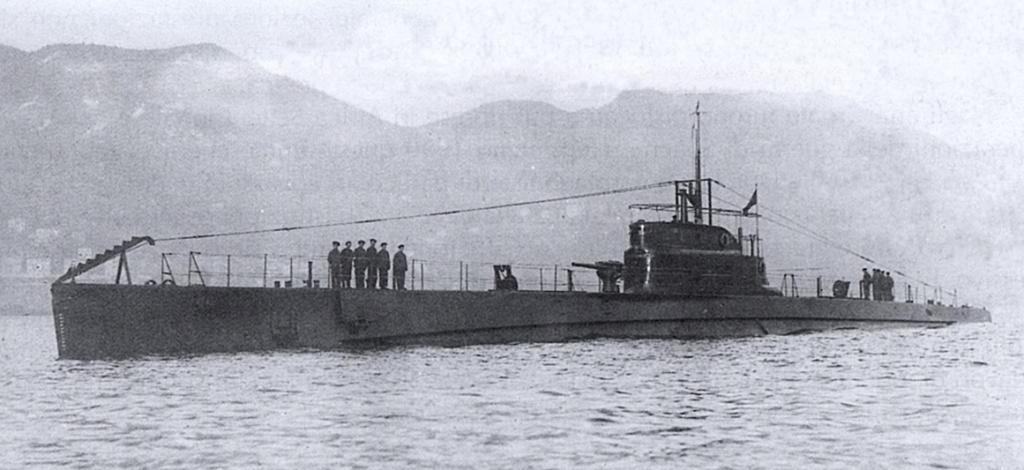

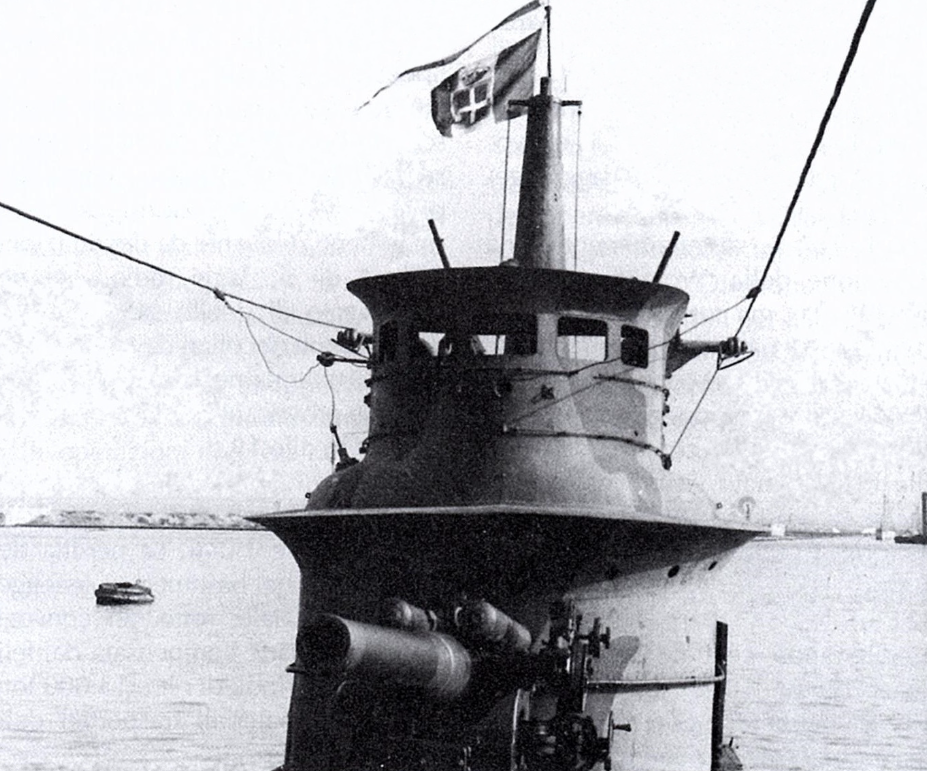

Turchese in Messina, Sicily

End of 1936

After completing his initial training, the boat made a long endurance cruise in the Dodecanese.

1937

Turchese carried out a training campaign in the Dodecanese and in the Mediterranean.

1938

Another training campaign in the Dodecanese and in the Mediterranean.

May 5th, 1938

Under the command of Lieutenant Francesco Coelli (1), the submarine Turchese took part in the naval magazine “H” organized in the Gulf of Naples for Adolf Hitler’s visit to Italy. Most of the Italian fleet took part in the review: the battleships Giulio Cesare and Conte di Cavour, the seven heavy cruisers of the I and III Divisions, the eleven light cruisers of the II, IV, VII and VIII Divisions, 7 “light explorers” of the “Navigatori” class, 18 destroyers (the Squadrons VII, VIII, IX and X, plus the Borea and the Zeffiro), 30 torpedo boats (the Squadrons IX, X, XI and XII, plus the old Audace, Castelfidardo, Curtatone, Francesco Stocco, Nicola Fabrizi and Giuseppe La Masa and the four “escort notices” of the Orsa class), as many as 85 submarines of the Submarine Squadron under the command of Admiral Antonio Legnani, and 24 MAS (Squadrons IV, V, VIII, IX, X and XI), as well as the training ships Cristoforo Colombo and Amerigo Vespucci, Benito Mussolini’s yacht, the Aurora, the royal ship Savoy and the target ship San Marco.

The Submarine Squadron, under the command of Rear Admiral Antonio Legnani, was the protagonist of one of the most spectacular moments of the parade, in which the 85 boats carried out a series of synchronized maneuvers. First, arranged in two columns, at 1.15 PM they pass opposite direction between the two naval squadrons proceeding on parallel routes. Then, at 1:25 PM, all the submarines made a simultaneous mass dive, proceeded for a short distance submerged and then emerged simultaneously and executed a salvo of eleven shots with their respective guns.

1. Promoted to Commander, Coelli died aboard the Heavy Cruiser Pola on March 3rd, 1941 during the Battle of Matapan.

May 1938

Turchese, part of the XXXIV Submarine Squadron (I Grupsom of La Spezia) along with Medusa, Jasper and Corallo, was among the numerous units (battleships Cesare and Cavour, heavy cruisers Zara, Pola, Fiume, Gorizia, Trento, Trieste and Bolzano, light cruisers Duca degli Abruzzi, Garibaldi, Eugenio di Savoia, Duca d’Aosta, Attendolo, Da Barbiano, Di Giussano, Colleoni, Cadorna, Diaz, Bande Nere, twenty destroyers of Squadrons VII, VIII, IX and X, 54 submarines of Squadrons XI, XII, XIII, XIV, XV, XXI, XXXIV, XLI, XLII) concentrated in Genoa for another naval review organized on the occasion of Benito Mussolini’s official visit to the city, the first in twelve years.

In his speech to the Genoese on 14 May, Mussolini declared: “… The guidelines of our policy are clear: we want peace, peace with everyone. (…) But peace, to be sure, must be armed. That is why I wanted the whole fleet to gather in Genoa: to show you and the Italians of the two most continental regions, which are Piedmont and Lombardy, what our real strength is on the sea. We want peace, but we must be ready with all our might to defend it, especially when we hear speeches, even from across the Atlantic, on which we must reflect. It is perhaps out of the question that the so-called great democracies are really preparing for a war of doctrines. However, it is good to know that, in this case, totalitarian states will immediately block and march to the end.“

The fleet remained in Genoa until the end of the month, open to visits by the civilian population: a total of 650,000 visitors flocked to see it, of which 430,000 were Genoese and 220,000 from the rest of Liguria, Piedmont, and Lombardy.

June 19th, 1938

Turchese received the combat flag in Riposto (TN Near Catania, Sicily), offered by the city, on the occasion of the twentieth anniversary of the battle of the Piave.

The ceremony for the delivery of the battle flag to the Turchese organized by the Fascist Party in Riposto

October 15th, 1938

Turchese was assigned to the submarine Command School.

Spring 1939

Turchese was deployed in Cagliari, as part of the LXXII Submarine Squadron along with Diapro, Coralllo and Medusa.

January 1st, 1940

Lieutenant commander Gustavo Miniero (1), 33, from Gragnano, took command of Turchese.

- Promoted to Commander, Miniero died on January 5th, 1942 aboard the submarine Ammiraglio Saint Bon.

June 9, 1940

Under the command of Lieutenant Miniero, Turchese sailed from Cagliari at 10.02 PM to form a barrage on the meridian of Capo Teulada, along with Adua, Axum and Aradam. Turchese, specifically, patrolling 35 miles south of Cape Teulada.

June 10th, 1940

Upon Italy’s entry into the World War II, Turchese was part of the LXXII Submarine Squadron based in Cagliari, along with Diaspo, Corallo, and Medusa.

June 13th, 1940

Tuirchse received orders to move to the Gulf of Lion, after which the boat patrolled the waters 15 miles east of Cape Creus until the evening of the 19th, in search of French and British merchant traffic.

June 21st, 1940

At 10:15 AM, the crew sighted three small military units from 20 km away in quadrant 0261, northeast of the Balearic Islands. Approaching up to 14 km, Captain Miniero realized that he was dealing with a large enemy formation thus gave up the chase at 11.48 AM.

Probably, the units sighted were the French destroyers of the 8éme Division de Contre-Torpilleurs, the fastest warships in the world.

At 10.05 PM Turchese returned to Cagliari, after having covered 1,052 miles.

July 3rd, 1940

The boat sailed from Cagliari at 2.16 PM, under the command of Lieutenant Gustavo Miniero, to lay in ambush in position 37°54′ N and 07°40′ E, forming a patrol line between Bona and Cap de Fer with Aradam (which sailed along with Turchese), Alagi and Axum.

July 6th, 1940

The boat returned to Cagliari at noon, after having covered 262 miles.

July 9th, 1940

Still under the command of Lieutenant Gustavo Miniero, Turchese sailed from Cagliari at 00.57 for a patrol in position 37°50′ N and 09°40′ E, between the island of Galite and Tunisia.

July 12th, 1940

At 2.25 AM, during the return navigation, the officer of the watch sighted an illuminated ship in position 38°24′ N and 09°19′ E. Turchese approached using the electric motors, to remain silent and avoid revealing its presence. The unknown ship behaves strangely (it seems to be stationary), so much so that it was believed that it is not a neutral ship – as it should be, given the lights on – but an enemy ship engaged in laying mines.

At 3:25 AM, Turchese launched a 533 mm torpedo from the forward tubes from only 500 meters away. The phosphorescent wake pointed straight to the center of the target, but the torpedo passed under the hull without exploding. At 3:26 AM a second torpedo was launched, again 533 mm and again 500 meters, but this too passed under the hull of the unknown ship. Commander Miniero wanted to try again with a third torpedo, and open fire with the cannon, but at 3.35 AM Turchese violently hit a metal object, at 3.38 AM a second collision occurs, more violent than the first. At 4:10 AM, the submarine broke contact and moved away (according to another source, the unknown ship would have been able to disengage thanks to the increased speed). At 11.05 AM Turchese returned to Cagliari, after having covered 354 miles.

August 1st, 1940

Still under the command of Lieutenant Gustavo Miniero, Turchese sailed from Cagliari at one o’clock in the morning for a patrol south of the Balearic Islands, in position 37°25′ N and 06°30′ E. It was to form a barrage along with the submarines Argo, Scirè, Neghelli, Medusa, Axum and Diaspro, arranged in two lines of three and four units spaced ten miles apart (while the distance between two submarines of the same line was twenty miles) north of Cape Bougaroni. The formation of the barrage was ordered by Supermarina following the report of the exit from Gibraltar of the British Force H (which sailed with the aircraft carriers H.M.S. Argus and H.M.S. Ark Royal, the battlecruiser H.M.S. Hood, the light cruiser H.M.S. Enterprise and the destroyers H.M.S. Faulknor, H.M.S. Foxhound, H.M.S. Foresight, H.M.S. Forester, H.M.S. Encounter, H.M.S. Gallant, H.M.S. Greyhound and H.M.S. Hotspur for operations “Hurry” and “Crush”, consisting respectively of sending to Malta twelve fighters launched by H.M.S. Argus and an air attack against Cagliari by planes that took off from H.M.S. Ark Royal).

Turchese was part of the line of four units, together with Diaspro, Axum and Medusa (which after two days had to be replaced by the submarine Luciano Manara following a breakdown). Force H, however, would move north of the area where the submarines were deployed, thus they were not able to attack.

August 9th, 1940

Turchese returnd at 11.40 AM to La Maddalena, after having covered 1,342 miles without any noteworthy encounters.

August 23rd, 1940

The boat left La Maddalena at one o’clock in the morning, under the command of Lieutenant Miniero, to transfer to Pula.

August 28th, 1940

Turchese arrived in Pula at 11.40 AM, after having covered 1,054 miles.

August 30th, 1940

The boat left Pula at 5.45 AM, still under the command of Lieutenant Miniero, to move to Monfalcone, where it arrived at 12.30 PM after having traveled 74 miles. There it entered the shipyard for works.

November 9th, 1940

Once the work was completed, Turchese completed a training patrol from Monfalcone, from 9.18 AM to 4.10 PM, covering 40 miles. The commander was still Lieutenant Gustavo Miniero.

November 22nd, 1940

Another training patrol from Monfalcone, from 9.30 AM to 3.50 PM, under the command of Lieutenant Miniero. The boat traveled 44 miles.

November 24th, 1940

Turchese left Monfalcone at 9.33 AM, under the command of Lieutenant Miniero, to move to Pula, where it arrived at 4.40 PM, after having covered 74 miles.

November 29th, 1940

Exited Pula for a training patrol from 9.03 AM to 9.53 AM, under the command of Lieutenant Miniero, covering five miles.

December 2nd, 1940

The boat left Pula at 9.10 AM, under the command of Lieutenant Miniero, to move to Rijeka, escorted by his twin boat Galatea. During the transfer navigation, it performed a diving test at 60 meters. Turchese arrived in Rijeka at 5.45 PM, after covering 63 miles.

December 5th, 1940

Lieutenant Pier Vincenzo Di Domenico, 31, from Milan, took command of Turchese, replacing Lieutenant Commander Miniero.

On the same day, the submarine made an exit from Rijeka, under the command of Lieutenant Di Domenico, from 12.12 AM to 4.35 PM for a diving test at 60 meters, returning to port after covering 18 miles.

December 6th, 1940

The boat left Rijeka at 8.36 AM to move to Pula, where it arrived at 2.36 PM, under the command of Lieutenant Pier Vincenzo Di Domenico, traveling 63 miles.

December 7th, 1940

Engines were fired up, from 14.10 AM to 14.40 AM, to change anchorage, always staying in Pula.

December 9th, 1940

Departure from Pula from 8.05 AM to 5.25 PM, under the command of Lieutenant Pier Vincenzo Di Domenico, escorted by the auxiliary escort ship F 134 Laurana, travrlling 61 miles.

December 11th, 1940

Left port for sea trials from Pula from 8 AM to 5.15 PM, under the command of Lieutenant Pier Vincenzo Di Domenico travelling 57 miles.

December 12th, 1940

Left Pula from 8.20 AM to 2.25 PM, under the command of Lieutenant Pier Vincenzo Di Domenico, for gyrocompass testing travelling 14 miles.

December 13th, 1940

Under the command of Lieutenant Pier Vincenzo Di Domenico, Turchese left Pula from 8.10 AM to 5.10 PM, along with the submarine Ettore Fieramosca and with the escort of the tugboat Tenace, for torpedo launch exercises with the torpedo boat Audace travelling 57 miles.

December 14th, 1940

Engines were fired up from 2.18 PM to 2.35 PM to change anchorage in the port of Pula.

December 26th, 1940

Turchese left Pula at 7.40 PM, under the command of Lieutenant Pier Vincenzo Di Domenico, to move to Brindisi.

December 28th, 1940

The boat arrived in Brindisi at 2.15 PM, after having covered 370 miles.

December 30th, 1940

Turchese sailed from Brindisi at ten o’clock in the morning for a patrol south of the Otranto Channel and west of Corfu, in position 39°30′ N and 19°10′ E, under the command of Lieutenant Pier Vincenzo Di Domenico. Together with the submarines Ambra and Filippo Corridoni, it protected traffic between Italy and Albania.

January 9th, 1941

At 7:25 AM, the Greek submarine Triton (Lieutenant Commander Dyonisios Zeppos) unsuccessfully attacked a submarine west of Othoni, in the Otranto Channel. It is possible that the submarine attacked was Turchese, which for its part, however, did not notice the attack.

January 10th, 1941

Turchse returned to Brindisi at 5:30 PM, after having covered 887 miles without any major events, apart from detecting engine noises.

January 22nd, 1941

Departure from Brindisi for sea trials from 9:00 AM to 12.30 PM, under the command of Lieutenant Pier Vincenzo Di Domenico travelling 18 miles.

January 29th, 1941

Departure from Brindisi for sea trials from 8.42 AM to 12.30 PM, under the command of Lieutenant Pier Vincenzo Di Domenico travelling 18 miles.

January 30th, 1941

Turchese set sail from Brindisi at ten o’clock, under the command of Lieutenant Pier Vincenzo Di Domenico, for a patrol off the Albanian coast, within a radius of ten miles from point 39°10′ N and 19°20′ E, to protect traffic between Italy and Albania.

February 10th, 1941

The boat returned to Brindisi at 6:15 PM, after having covered 908 miles without detecting anything more than distant engine noise.

February 21st, 1941

Turchese sailed from Brindisi at 1:00 PM, under the command of Lieutenant Pier Vincenzo Di Domenico, for a patrol west of Corfu, within a radius of ten miles from point 39°10′ N and 19°20′ E, again to protect convoys sailing to and from Albania.

March 4th, 1941

The boat returned to Brindisi at 2.50 PM, after having covered 985 miles without major events.

March 15th, 1941

Turchese left Brindisi at 10:00 PM, under the command of Lieutenant Pier Vincenzo Di Domenico, to move to Crotone.

March 16th, 1941

The boat arrived in Crotone at 5.35 PM, after having covered 179 miles.

March 20th, 1941

Turchese left Crotone at 2:00 PM, under the command of Lieutenant Pier Vincenzo Di Domenico, to move to Cagliari.

Some sources erroneously state that on this date Turchese unsuccessfully attacked a destroyer, being bombarded with depth charges, but this is a mistake; There is no record of this incident in the mission report.

March 22nd, 1941

The boat arrived in Cagliari at 5.30 PM, after having covered 485 miles.

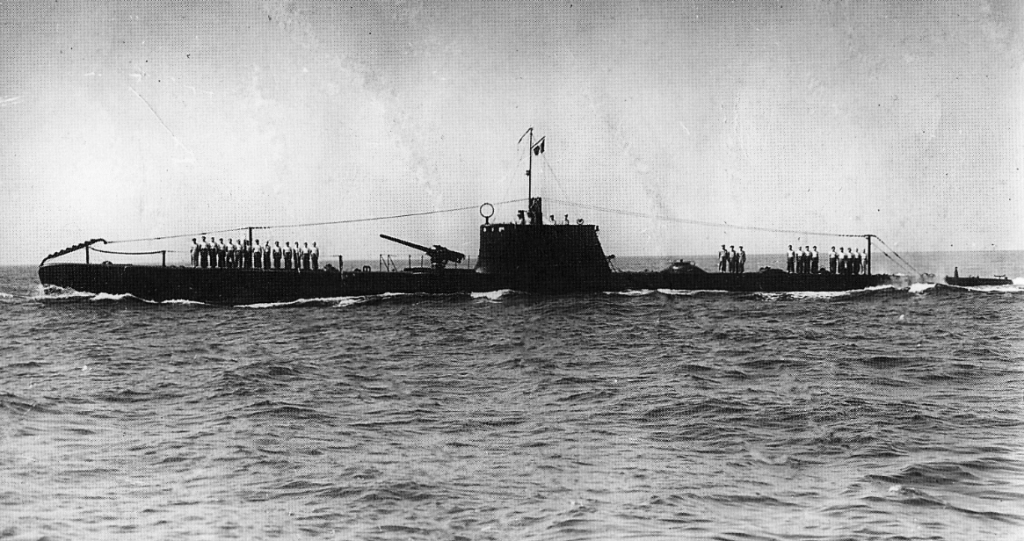

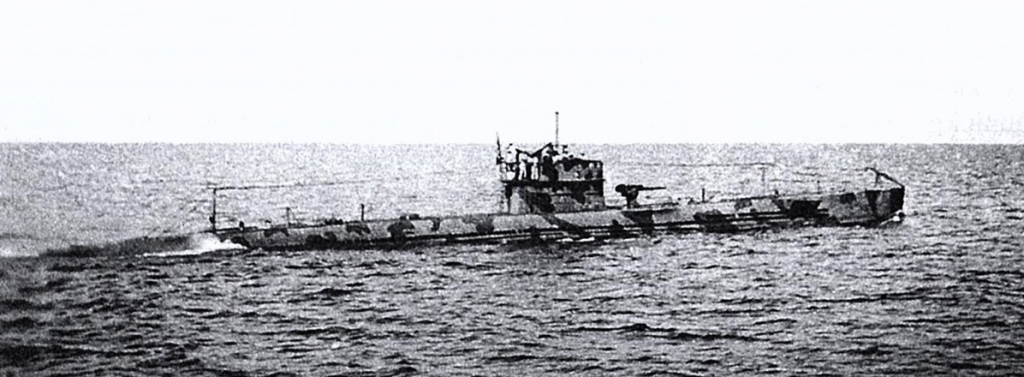

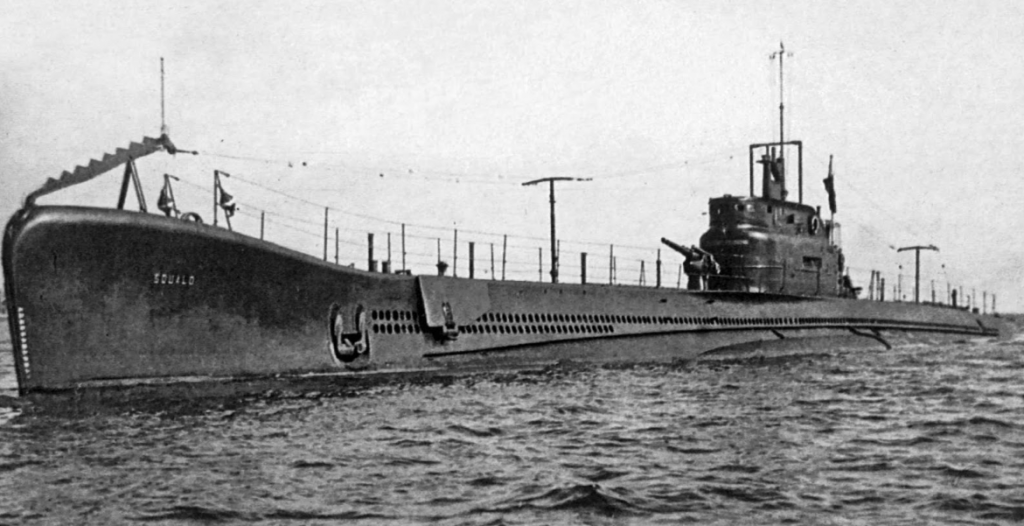

Turchese at sea

March 31st, 1941

The boat left Cagliari from 8:00 AM to 12.15 PM, under the command of Lieutenant Pier Vincenzo Di Domenico, for sea trials travelling 31 miles.

April 3rd, 1941

Turchese left Cagliari at 12.50 PM, under the command of Lieutenant Pier Vincenzo Di Domenico, for a patrol north of Cape Blanc, within a radius of twenty miles from point 37°30′ N and 09°50′ E forming a barrage with its twin boat Corallo.

April 9th, 1941

The boat returned to Cagliari at 5.15 PM, after having traveled 552 miles without sighting anything but ships of Vichy France.

April 18, 1941

Turchese left Cagliari at eight o’clock in the evening, under the command of Lieutenant Pier Vincenzo Di Domenico, to move to Messina.

April 20th, 1941

The boat arrived in Messina at ten o’clock in the morning, after having covered 360 miles.

April 21st, 1941

Under the command of Lieutenant Pier Vincenzo Di Domenico, Turchese sailed from Messina at 6.56 PM for a patrol in the Gulf of Sollum and off Marsa Matruh, within a radius of 20 miles from point 32°10′ N and 27°30′ E, along an axis oriented from northeast to southwest.

April 30rd, 1941

At 5:27 PM, Turchese, engaged in hydrophone surveillance while submerged, when it was suddenly shaken by two explosions, which were attributed to aircraft bombs. At 6:42 PM, eight more explosions occurred, and then more until 7:40 PM.

They were not aircraft bombs but depth charges, dropped in position 32°59′ N and 27°52′ E by the British destroyers H.M.S Jaguar and H.M.S. Juno, which wrongly believe that they have sunk the attacked submarine (H.M.S. Juno will have five dead and eleven wounded among the crew due to the premature explosion of a depth charge). To escape the hunt, Turchese descended to a depth of 90-95 meters.

May 1st, 1941

More explosions were heard, but at a great distance.

May 3rd, 1941

Following trouble with the diesel engines, Turchese aborted its mission and headed towards Leros.

May 7th, 1941

Turchese reached Leros at 2.40 PM, after having covered 1,451 miles.

May 26th, 1941

The boat left Leros for sea trials from 8.05 AM to 12.19 PM, under the command of Lieutenant Pier Vincenzo Di Domenico travelling 23 miles.

May 27th, 1941

The boat left Leros from 7.38 AM to 10.43 AM, under the command of Lieutenant Pier Vincenzo Di Domenico, for sea trials covering 3 miles.

May 31st, 1941

Turhse left Leros at 3:20 AM, under the command of Lieutenant Pier Vincenzo Di Domenico, for a patrol south of the island of Kupho (southeast of Crete), within a radius of twenty miles from 33°50′ N and 26°00′ E.

June 5th, 1941

At 8:43 PM, twenty miles southwest of Cape Krio, a submarine was sighted two thousand yards away. Captain Di Domenico decided to dive as a precaution, but during the diving phase the boat was identified as Italian. It was in fact Smeraldo, which in turn recognized the other unit as Italian (although it was wrong about the class, believing to be the Fisalia) and carried out the recognition signals. Subsequently, Turchese headed to Taranto due to engine problems.

June 8th, 1941

The boat arrived in Taranto at 2.35 PM, after having covered 1,040 miles.

June 20th, 1941

The boat left Taranto from 2.45 PM to 5.50 PM, under the command of Lieutenant Pier Vincenzo Di Domenico, for gyrocompass testing covering 2 miles.

June 24th, 1941

Engines were fired up for 10 minutes for a change of anchorage in the port of Taranto.

August 21st, 1941

Departure from Taranto from 11.49 AM to 7.30 AM, under the command of Lieutenant Pier Vincenzo Di Domenico, for sea trials, with the escort of the auxiliary escort ship F 46 Limbara travelling 29 miles.

August 23rd, 1941

Left Taranto from 2.14 PM to 4.24 PM, under the command of Lieutenant Pier Vincenzo Di Domenico, for gyrocompass testing covering 2 miles.

August 24th, 1941

Left Taranto for sea trials from 8.42 AM to 5.52 PM, under the command of Lieutenant Pier Vincenzo Di Domenico. travelling 63 miles.

August 27th, 1941

Left Taranto for sea trials from 8.05 AM to 5.10 PM, under the command of Lieutenant Pier Vincenzo Di Domenico travelling 60 miles.

August 29th, 1941

Departure for sea trials from Taranto from 11:00 AM to 6.10 PM, under the command of Lieutenant Pier Vincenzo Di Domenico, with the escort of the torpedo boat Altair travelling 33 miles.

September 1st, 1941

Turchse left Taranto at 8.55 AM, under the command of Lieutenant Pier Vincenzo Di Domenico, to move to Messina.

September 2nd, 1941

The boat arrived in Messina at 12.10 PM, after having covered 255 miles.

September 3rd, 1941

The boat left Messina at 7:00 PM to move to Cagliari, still under the command of Lieutenant Di Domenico.

September 5th, 1941

The boat arrived in Cagliari at 7.07 AM, after covering 351 miles.

September 9th, 1941

Departure from Cagliari for sea trials from 7.30 AM to 1.55 PM, under the command of Lieutenant Di Domenico travelling 26 miles.

September 11th, 1941

Turchese sailed from Cagliari at 1.40 PM, under the command of Lieutenant Di Domenico, for a patrol in position 38°00′ N and 06°00′ E, north of Capo Bougaroni forming a barrage together with Adua and Axum.

September 14th, 1941

Turchese was ordered to move to a new ambush sector, centered on 38°10′ N and 04°00′ E.

September 16th, 1941

The boat returned to Cagliari at 9.33 AM, after having covered 685 miles without any major events.

September 22nd, 1941

Departure from Cagliari for sea trials from 7.08 AM to 12.24 PM, under the command of Lieutenant Di Domenico, along with the submarines Adua and Serpente and with the escort of the torpedo boat Giuseppe Cesare Abba and the auxiliary minelayer R 176 Balear travelling 35 miles.

September 23rd, 1941

Turchese sailed from Cagliari at 7:00 PM, under the command of Lieutenant Di Domenico, for a patrol south of the Balearic Islands, between Cape Palos and Cape Caxine (south/southwest of Ibiza), in an area bounded by the meridians 00°20′ E and 00°40′ E and the parallels 36°50′ N (or 36°30′ N) and 37°30′ N. It was part of a barrage together with the Adua, in contrast to the British operation ‘Halberd’. As part of this operation, Force H lefty Gibraltar, with the battleships H.M.S. Prince of Wales, H.M.S. Rodney and H.M.S. Nelson, the aircraft carrier H.M.S. Ark Royal and the destroyers H.M.S. Duncan, H.M.S. Fury, H.M.S. Lance, H.M.S. Legion, H.M.S. Lively, H.M.S. Gurkha, H.M.S. Zulu, Isaac Sweers (Dutch), Garland (Polish) and Piorun (Polish). The formation was divided by the British into various sub-groups, which departed at different times between September 24th and 25th. The purpose was to protect the navigation to Malta of a convoy with supplies (WS. 11X, formed by the military tanker Breconshire and the cargo ships Ajax, City of Lincoln, City of Calcutta, Clan MacDonald, Clan Ferguson, Rowallan Castle, Imperial Star and Dunedin Star with a combined cargo of 81,000 tons of supplies and the direct escort of the light cruisers H.M.S. Edinburgh, H.M.S. Sheffield, H.M.S. Euryalus, H.M.S. Kenya and H.M.S. Hermione and the destroyers H.M.S. Cossack, H.M.S. Farndale, H.M.S. Foresight, H.M.S. Forester, H.M.S. Heythrop, H.M.S. Laforey, H.M.S. Lightning and H.M.S. Oribi of Force X), which would take place at the same time as the navigation of another convoy (three unloaded merchant ships, escorted by a corvette) from Malta to Gibraltar and with a diversionary action by the Mediterranean Fleet in the eastern Mediterranean.

The departure of Force H in several groups, and the routes followed by them until the meeting (which took place on the morning of September 27th, one hundred miles south of Cagliari), deceived the Italian commands, who mistakenly believed that the purpose of the operation was a naval bombardment against targets on the coasts of the Peninsula (as attested by the “Notiziario 73” of “Maristat Informazioni”, on the morning of September 25th, according to which “The purpose of the mission would be retaliation against the Italian coasts”). To counter this hypothetical bombardment, Supermarina sent four submarines east of the Balearic Islands, three more southwest of Sardinia, three south/southwest of Ibiza and five in the Ligurian Sea. Turchese, Adua, Dandolo, Squalo, Delfino and Fratelli Bandiera were sent north of Cape Ferrat, Narvalo north of Cape Bon.

Turchese, Adua and Dandolo reached the assigned areas only after the British formation has already crossed them. Maricosom, as a consequence, ordered all submarines to move further south, attempting to intercept the British forces (whose real objective was meanwhile understood by Supermarina on the morning of the 27th, when news of the existence of a convoy bound for Malta arrived) during the re-entry phase, communicating at 8.45 PM on the 27th: “Enemy naval force already attacked and damaged by ARMERA (STOP) In search and attack act with maximum commitment and precision to inflict to the enemy further and more serious damage possible (STOP) I am sure that you will prove worthy of the trust that the Navy places in you (STOP)”. But even these new orders will not bring results.

Equally unsuccessful was the departure to sea of the battle squadron under the command of Admiral Angelo Iachino (battleships Littorio and Vittorio Veneto, heavy cruisers Trento, Trieste and Gorizia, light cruisers Muzio Attendolo and Luigi di Savoia Duca degli Abruzzi, destroyers Granatiere, Bersagliere, Fuciliere, Ascari, Lanciere, Cuirassier, Carabiniere, Folgore, Maestrale, Grecale, Scirocco, Vincenzo Gioberti, Nicoloso Da Recco and Emanuele Pessagno).

September 30th, 1941

At 5:03 AM, a message was received reporting the sighting by the Adua, at 3:50 AM, of a group of eleven destroyers, which, however, given their position and course, would pass much further north than the position of Turchese.

At 10.17 AM smoke was sighted from 14,000 meters, in position 36°49′ N and 00°24′ E. Turchese maneuvered to approach, and at 10.39 AM, having dropped the distance to 6,000 meters, managed to distinguish two Arethusa-class cruisers and two destroyers. At 11:10 AM, while Turchese was at a depth of 19 meters, six explosions were detected quite close. Commander Di Domenico decides to descend to 40 meters. At 1:39 PM, the hydrophones no longer picked up any noise.

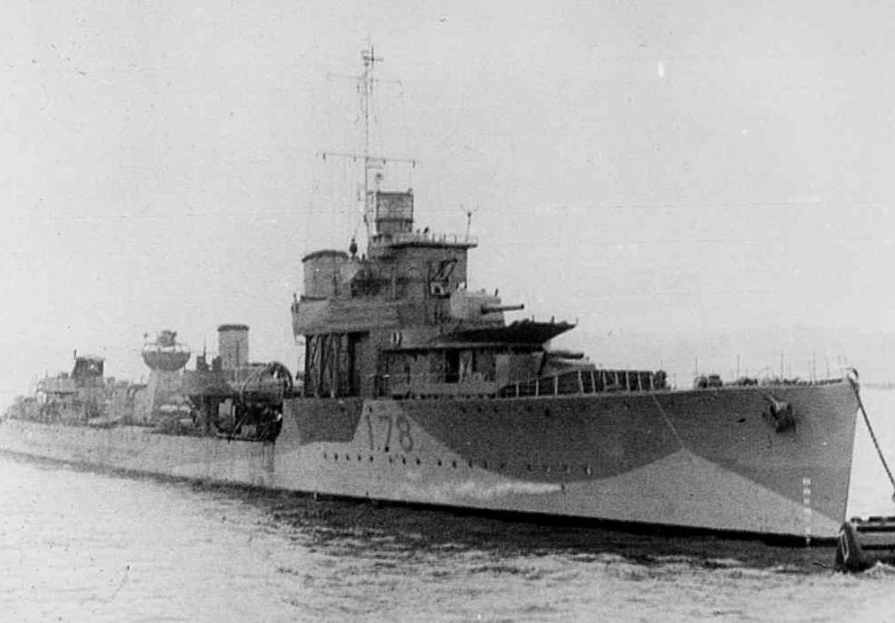

The destroyers sighted by Turchese were probably the British H.M.S. Legion and H.M.S. Gurkha, which formed the advanced screen of Force H returning from operation “Halberd”. in a few hours they would sink the Adua.

October 2nd, 1941

At 6.50 AM a submarine, probably Italian, was sighted from 2,000 meters away, in position 37°15′ N and 03°12′ E. Given the poor visibility, however, Turchese maneuvers as a precaution to get away.

October 4th, 1941

The boat returned to Cagliari at 10.25 PM, after having covered 1,258 miles.

October 15th, 1941

Departure from Cagliari for sea trials from 8.05 AM to 12.30 PM, under the command of Lieutenant Di Domenico travelling 30 miles.

October 16th, 1941

Turchese sailed from Cagliari at 11.40 PM, under the command of Lieutenant Di Domenico, for a patrol north of Cap de Fer, together with the submarines Alagi, Serpente, Diaspro and Aradam, in an area between the parallels 37°40′ N and 37°50′ N (for another source, 37°10′ N and 37°20′ N) and the meridians 06°40′ N and 07°20′ E. The five submarines formed a barrage between 37°10′ N and 37°50′ N, each occupying an area of ten miles radius (another source speaks of a much larger barrage in the Strait of Sicily, formed by Ambra, Alagi, Ametista, Corallo, Fratelli Bandiera, Diaspro, Serpente, Squalo, Turchese, Delfino, and Narvalo).

October 21st, 1941

Turchese returned to Cagliari at 11:16 AM, after having traveled 552 miles without having sighted anything but ships of Vichy France.

October 27th, 1941

Departure from Cagliari for sea trials from 1.10 PM to 4.15 PM, under the command of Lieutenant Di Domenico, with the escort of the Balear travelling 15 miles. At the end of the mission, Lieutenant Di Domenico disembarked and was replaced by Lieutenant Commander Giovanni Cunsolo, 31, from Petralia Sottana.

November 11th, 1941

Under the command of Lieutenant Commander Giovanni Cunsolo, Turchese sailed from Cagliari at 6.30 PM for a patrol in the “K.1” area, between Cape Bon and Ras Mustafà (more precisely, between the parallel 37°12′ N and the Tunisian coast, and between the meridians 06°20′ E and 06°30′ E) forming a barrage with Alagi, Axum, and Aradam.

November 13th, 1941

At six o’clock in the morning an illuminated merchant ship was sighted, 80 miles by 000° from Cape Blanc. Turchese approached 6,000 meters and sees that the ship is heading towards Bizerte. In the following days, only Italian or Vichy French ships were sighted.

November 14th, 1941

At 3:04 AM Turchese was sighted by the Aradam.

November 17th, 1941

Turchese returned to Cagliari at 4.10 PM, after having covered 672 miles.

December 1st, 1941

Lieutenant Commander Cunsolo left command of Turchese, which was again taken over by Lieutenant Pier Vincenzo De Domenico.

December 18th, 1941

Under the command of Lieutenant De Domenico, Turchese sailed from Cagliari at 8.25 PM for a patrol off Cape Bougaroni, in an area bounded by the Algerian coast, the meridian 37°30′ N and the parallels 06°20′ E and 06°30′ E forming a barrage together with Axum, Alagi and Aradam.

December 19th, 1941

At 9.40 AM, a German submarine (possibly U 74) was sighted 3,000 meters away, in position 38°05′ N and 07°47′ E, which made an indecipherable signal. Turchese continued on its course.

December 21st, 1941

At 1.24 AM a steamer, believed to be French, was sighted in position 37°21′ N and 06°22′ E.

December 22nd, 1941

At 2.55 AM another French steamer was sighted, in position 37°32′ N and 06°28′ E.

December 23rd, 1941

At 2:45 PM, ship noises were picked up on the hydrophone, on a 248° bearing. However, their direction varied considerably. Turchese headed towards them, and at 5.05 PM, in position 37°21′ N and 06°26′ E (off Cape Bougaroni), Turchese sighted two cruisers identified as of the Newcastle class and four destroyers believed to be of the Jervis class, sailing southwest at 25 knots, 12 km away; It send the discovery signal. However, it could not get closer than 7,000 meters.

The ships sighted were probably the British light cruiser H.M.S. Dido and the destroyers H.M.S. Zulu, H.M.S. Gurkha, H.M.S. Arrow, H.M.S. Foxhound and H.M.A.S. Nestor, the latter Australian.

December 25th, 1941

Turchese returned to Cagliari at 4.30 PM, after having covered 763 miles.

January 1st, 1942

At 8 PM Turchese sailed from Cagliari under the command of Lieutenant Di Domenico, to form a barrage between 60 and 100 miles south of Malta (line passing through point 35°00′ N and 13°00′ E) together with Alagi, Aradam and Axum, to protect the convoys sailing between Italy and Libya. Their task was to spot and attack any British naval forces that might take to the sea to counter Operation M. 43, consisting of sending a large convoy of supplies to Libya. In total, as many as eleven submarines (Turchese, Aradam, Platino, Onice, Galatea, Beilul, Delfino, Alagi, Axum, Zaffiro and Dessiè) were deployed in ambush on the probable routes that a British naval formation could take; one group (Turchese, Aradam, Axum, Platino, Onice, Alagi and Delfino) was deployed to the east of Malta, against possible arrivals from this island, another (Beilul, Galatea and Dessiè) further east, between Crete and Cyrenaica, on the route that would follow a formation that takes the sea from Alexandria. The submarines had an offensive-exploratory assignment during the day and a total offensive at night.

Turchese, specifically, was assigned a patrol area bounded by the meridians 14°00′ E and 14°40′ E and the parallels 34°20′ N and 34°40′ N. (Another source speaks of a barrage between Tobruk and Ras Aamer, together with Ametista and Galatea).

No British naval force would be able to attack the convoy, as the Mediterranean Fleet had been reduced to a minimum as a result of the losses inflicted at the end of 1941 by mines, Italian assault craft and German submarines (a situation of which, however, Rome was not aware, so as to lead to extreme precautionary measures such as this deployment of underwater units to protect the navigation of an important convoy such as “M. 43”); The convoy reached its destination unscathed, bringing to Libya 15,379 tons of fuel, 2,417 tons of ammunition, 10,242 tons of various materials, 144 tanks, 520 vehicles and 901 officers, non-commissioned officers and soldiers.

January 2nd, 1942

A breakdown forced the boat to divert to Trapani. It enters the port at 4.50 PM, but once the fault was repaired, it left at 7:00 PM and reached the area assigned for the ambush.

January 8th, 1942

Turchese returned to Cagliari at 7.40 PM, after having covered 1,027 miles.

January 16th, 1942

Departure from Cagliari for sea trials from 1.45 PM to 5.15 PM, under the command of Lieutenant Di Domenico travelling 14 miles.

January 28th, 1942

The boat set sail from Cagliari at 2.20 PM, under the command of Lieutenant Di Domenico, to patrol the area between meridians 07°00′ E and 07°10′ E and the parallels 37°30′ N and 38°00′ N together with Alagi, Aradam, Axum and Brin (with which it formed a barrage). At 4:46 PM, however, he was called back to base, returning to Cagliari at 7:30 PM, after having covered 46 miles.

February 3rd, 1942

Departure from Cagliari for sea trials from 12.25 PM to 5.35 PM, under the command of Lieutenant Di Domenico travelling 33 miles.

February 9th, 1942

Turchese sailed from Cagliari at 15.35, under the command of Lieutenant Di Domenico, to form a barrage off Philippeville and north of Cape Bougaroni, together with Aradam and Axum. It patrolled a sector between the meridians 06°00′ E and 06°10′ E and between the parallels 37°30′ N and 38°00′ N.

February 11th, 1942

At 3 PM, a submarine was sighted heading west; it was believed to be the Brin.

February 21st, 1942

Turchese returned to Cagliari at 11.10 AM, after having covered 1,143 miles.

February 27th, 1942

At 12.38 PM Turchese set sail from Cagliari, under the command of Lieutenant Di Vincenzo, for a patrol off the Algerian coast, together with Aradam, Axum and Brin. It was assigned a patrol a sector between the meridians 03°40′ E and 04°40′ E and the parallels 37°20′ N and 37°30′ N.

March 4th, 1942

Turchese returned to Cagliari at 4.30 PM, after having traveled 765 miles sighting only ships of Vichy France.

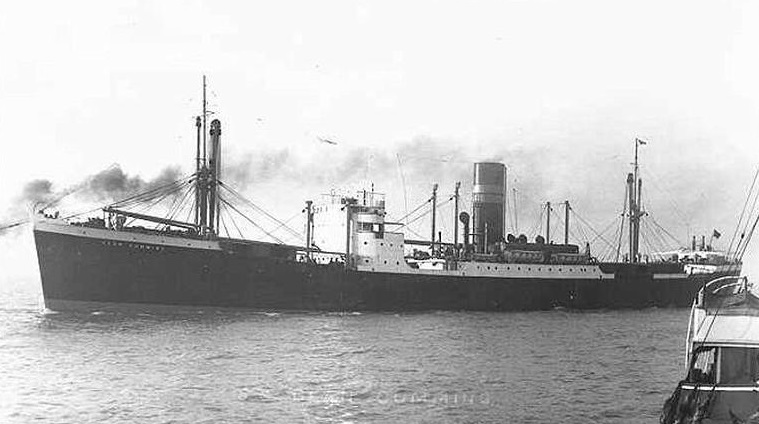

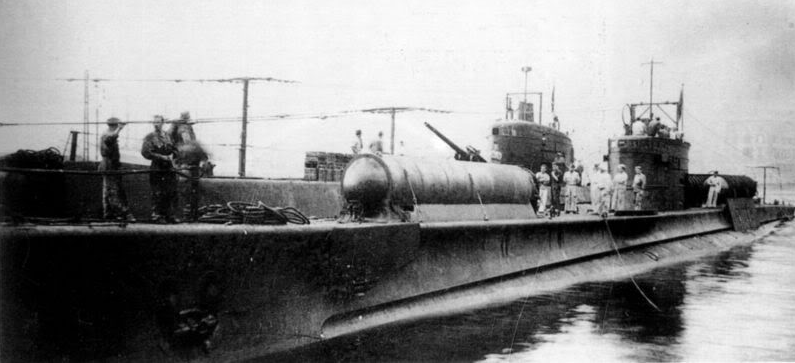

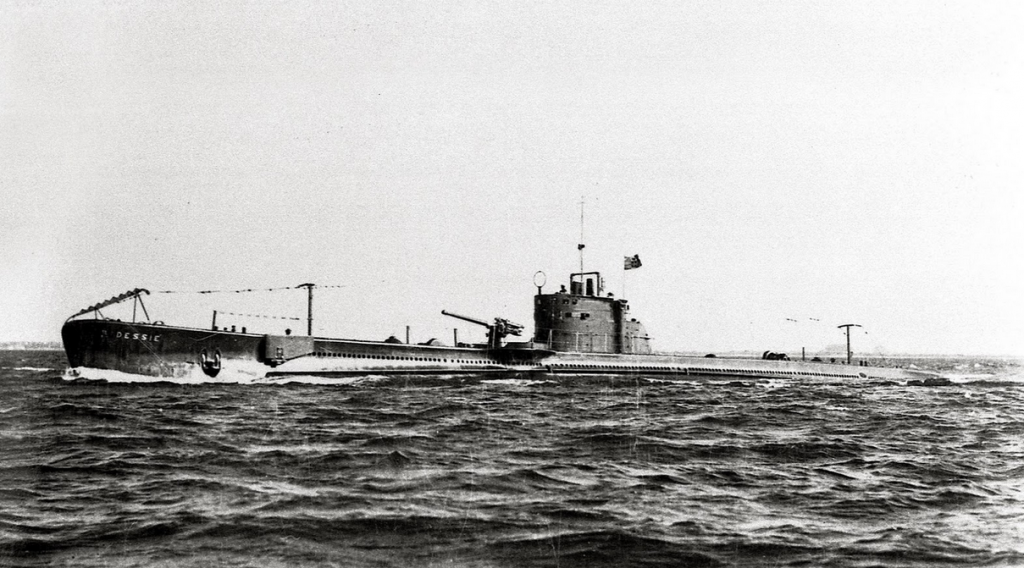

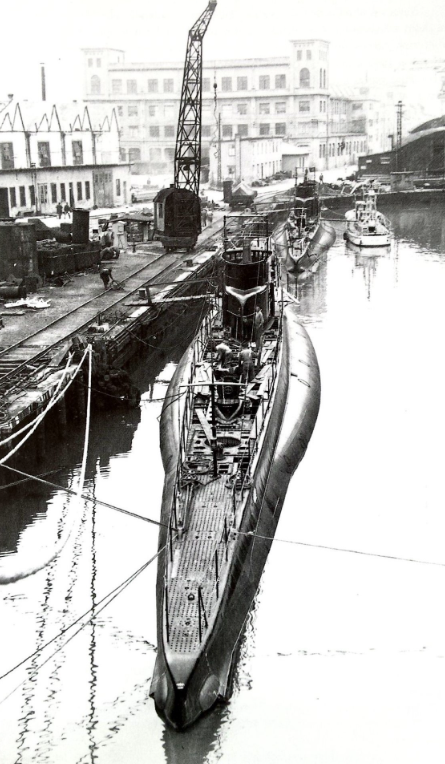

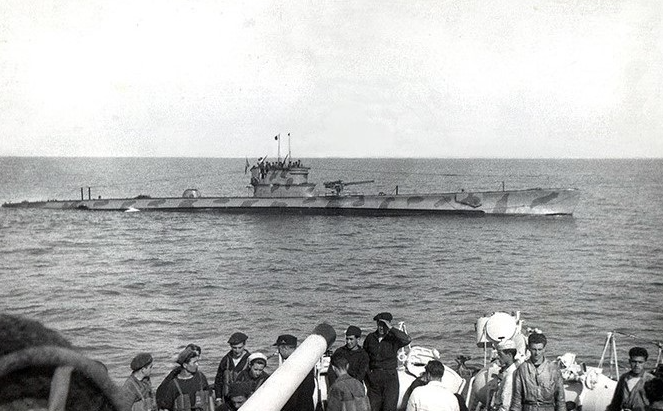

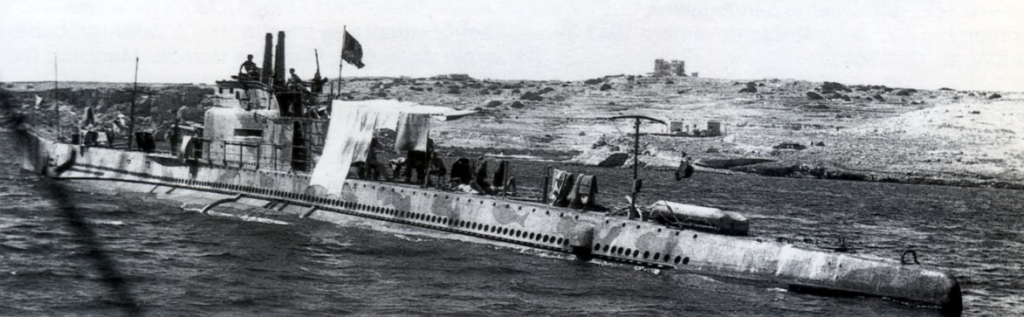

Turchese in 1942.

Erminio Bagnasco & Achille Rastelli noted that the boat in this picture was often identified as the Axum.

The crew in the foreground are those of the torpedo boat of Spica class.

(“Sommergibili in Guerra” Erminio Bagnasco & Achille Rastelli)

March 27th, 1942

The boat set sail from Cagliari at 10.05 PM, under the command of Lieutenant Di Domenico, to form a barrage off Capo Bougaroni together with the Aradam (and, according to another source, Narvalo and Santorre Santarosa). It was assigned a patrol area bounded by the meridians 05°20′ E and 06°20′ E and the parallels 37°10′ N and 37°20′ N; The task of the submarines was to intercept Force H (under the command of Admiral Neville Syfret), which left Gibraltar and headed east, should it go there. However, the British formation, whose purpose is to launch aircraft intended to reinforce the Malta squadrons (this is Operation “Picket II”. The aircraft carriers H.M.S. Eagle and H.M.S. Argus set sail from Gibraltar on March 27th with the escort of the battleship H.M.S. Malaya, the light cruiser H.M.S. Hermione and the destroyers H.M.S. Active, H.M.S. Anthony, H.M.S. Blankney, H.M.S. Croome, H.M.S. Duncan, H.M.S. Exmoor, H.M.S. Laforey, H.M.S. Lightning and H.M.S. Wishart, launching on March 29th 8 Supermarine Spitfire fighters that reached Malta, while it will not be possible to launch, as planned, 6 Fairey Albacore torpedo bombers).

March 30th, 1942

At 5:12 PM, while Turchese was heading to intercept an enemy cruiser reported at 8:09 PM the previous day southwest of La Galite, an aircraft was sighted 7,000 meters away, in position 37°25′ N and 06°29′ E. The submarine dove. On board, it was believed that the cruiser passed about 10 miles away.

April 1st, 1942

At three o’clock in the morning, a large seaplane, identified as a PBY Catalina, was sighted in position 37°40′ N and 06°26′ E, 1,000 meters away. Turchese dove precipitously as five bombs explode, causing only minor damage.

The attacker was indeed a Catalina, the “J” aircraft (serial number AJ. 160) of the 202nd Squadron of the R.A.F., piloted by Lieutenant I. F. Edgar, which detected Turchese on radar from 8 miles and then also sighted it optically on route 075°, dropping its bombs (eight depth charges, one of which, however, did not drop due to a failure) from an altitude of just over 20 meters while the submarine was diving. Edgar later reported that he had spotted a large patch of naphtha at the site of the attack.

April 2nd, 1942

Turchese reached Cagliari at 9.38 am, after covering 643 miles.

April 4th, 1942

The boat sailed from Cagliari at 1.18 AM, again under the command of Lieutenant Di Domenico, to patrol the “K.1” area north of Cape Bon (bounded by the meridians 11°00′ E and 11°05′ E, by the parallel 37°12′ N and by the Tunisian coast), forming a barrage with the Aradam, which at the same time would patrol the “K.2” area, north of Cape Kelibia, with the dual purpose of protecting Italian convoys bound for Libya from incursions by British naval forces based in Malta, and to attack any isolated British traffic that might pass through these waters. The Maricosom Operation Order (209/SRP of 3 April, 7.45 PM) establishes: “Confidential personnel (STOP) Executive ambushes Kappa one submarine Turchese and Kappa two submarine Aradam (STOP) Turchese submarine outward route number one (semialt) return route number four with return to Trapani its new location (STOP) Aradam outbound route number one (semialt) return route number five with return to Trapani its new location (STOP) Leave ambush to order (STOP) Partial modification of the general order of operation Kappa during ambush during daylight hours, remain perched on the bottom without coming periscope altitude for listening to SITES (STOP) instead of sunset day five, arrive on ambush points as soon as possible after performed hidden navigation daylight hours day four”.

April 8th, 1942

At 9:20 PM, a message was received about the sighting of a cruiser and a destroyer sailing westward. Turchese and Aradam were ordered to approach the African coast. Turchese moved to just 2 miles from Cape Bon, but it did not spot anything.

April 11th, 1942

The boat returned to Cagliari at 8.50 AM, after having covered 674 miles.

April 18th, 1942

The boat left Cagliari at 14.05, under the command of Lieutenant Di Domenico, to move to Trapani.

April 19, 1942

Turchese arrived in Trapani at 10.40 am, after having covered 181 miles.

April 20th, 1942

At 3.40 PM Turchese, still under the command of Lieutenant Di Domenico, sailed from Trapani to patrol an area between the meridians 09°20′ E and 09°40′ E and the parallels 38°00′ N and 38°40′ N, in which an enemy naval force was reported. At 1:41 PM, however, the boat was recalled to base, where it returned at 9:55 PM, after having traveled 50 miles.

May 1st, 1942

The boat set sail from Trapani at 7.52 PM, under the command of Lieutenant Di Domenico, for a patrol south of Formentera, in an area between the meridians 01°20′ E and 01°40′ E and the parallels 37°40′ N and 38°20′ N.

May 8, 1942

At 00:10 it was informed of a convoy sailing eastwards, but it was not in a suitable position to attempt to intercept it (it was located at 38°18′ N and 01°31′ E). At eight o’clock in the evening Turchese received orders to move 20 miles to the south.

May 9th, 1942

At 12:43 PM, a Short Sunderland seaplane was sighted from 7,000 meters away, in position 37°27′ N and 01°37′ E.

May 11th, 1942

At 5:00 PM, while in position 37°27′ N and 01°27′ E, Turchese received a signal of discovery relating to a cruiser sighted southwest of the Galite, sailing eastwards. The boat headed to intercept it, but at 8:00 PM received orders to move 40 miles to the south, a position it reached at 11:53 PM. It dove to make hydrophones listening but did not pick up any noise.

May 15th, 1942

At 2.33 PM, in position 38°05′ N and 04°20′ E, the French steamer Île Rousse was sighted, sailing on route 325°.

May 17th, 1942

The boat returned to Trapani at 10.15 AM, after having covered 1842 miles.

May 21st, 1942

The boat set sail from Trapani at 9.08 PM, under the command of Lieutenant Di Domenico, to move to La Spezia.

May 23rd, 1942

The boat arrived in La Spezia at 9.25 pm, after having covered 400 miles.

May 29TH, 1942

The boat left La Spezia at 7.30 AM, under the command of Lieutenant Di Domenico and escorted by MAS 566, to move to Genoa, where he arrived at 1.43 PM, after having covered 56 miles. In Genoa he entered the SHIPYARD for a period of renovation work.

During the works, two changes of command took place: on June 20TH, Lieutenant Di Domenico handed over command to Second Lieutenant Sergio Parodi, 25, from Pistoia, who on July 15TH handed it over to Lieutenant Giandaniele Asquini, 27, from Udine.

August 6th, 1942

At the end of the work, Turchese left Genoa from 10.10 PM to 4.30 PM, under the command of Lieutenant Giandaniele Asquini, for sea trials travelling 26 miles.

August 9th, 1942

Departure from Genoa from 9.09 AM to 3.08 PM, under the command of Lieutenant Giandaniele Asquini, for sea trials travelling 47 miles.

August 1th1, 1942

Turchese left Genoa at 9.55 AM, under the command of Lieutenant Giandaniele Asquini, to move to La Spezia, where it arrived at 3.46 PM, after having covered 53 miles.

August 14th, 1942

Departure from La Spezia for sea trials from 8.10 AM to 1.15 AM and from 3:00 PM to 6.30 PM, under the command of Lieutenant Giandaniele Asquini travelling 45 miles.

August 17th, 1942

Departure from La Spezia for sea trials from 10.36 AM to 12.03 PM, under the command of Lieutenant Giandaniele Asquini covering 8 miles.

August 28th, 1942

Departure from La Spezia for sea trials from 2.40 PM to 6.20 PM, under the command of Lieutenant Giandaniele Asquini travelling 25 miles.

August 29th, 1942

Turchese sailed from La Spezia at 8.24 AM, under the command of Lieutenant Giandaniele Asquini, for an exercise; after a stop in Portovenere from 5.30 PM to 8.06 PM, Turchese went out to sea again to continue the sea trial.

August 30th, 1942

Turchese returned to La Spezia at 00.30, after having covered a total of 81 miles.

September 1st, 1942

Turchese left La Spezia at 11.02 AM, under the command of Lieutenant Giandaniele Asquini, for sea trials. At 11.45 PM, after covering 6 miles, it moored at the Fezzano buoy.

September 2nd, 1942

Turchese left the Fezzano buoy at seven in the morning for a training outing, after which it returned to La Spezia at 3.50 PM, after having covered 36 miles.

September 3rd, 1942

Under the command of Lieutenant Giandaniele Asquini, Turchese left La Spezia at 12.26 to move to Trapani, escorted by MAS 509 in the initial stretch of navigation.

At 2:20 PM it was informed by the light cruiser Attilio Regolo of the sighting of an enemy submarine in quadrant 7648.

September 5th, 1942

Turchese arrived in Trapani at 9.30 AM, after having covered 416 miles.

September 8th, 1942

Exit from Trapani for sea trials from 7.45 AM to 1.06 PM, under the command of Lieutenant Giandaniele Asquini travelling 24 miles.

September 11th, 1942

Exit from Trapani for sea trials from 7.50 AM to 12.40 PM, under the command of Lieutenant Giandaniele Asquini travelling 20 miles.

September 22nd, 1942

Exit from Trapani for sea trials from 8.32 to 11.47, under the command of Lieutenant Giandaniele Asquini travelling 18 miles.

October 19th, 1942

After embarking German G7e (TN Electric) torpedoes, Turchese sailed from Trapani at 1.10 PM, under the command of Lieutenant Giandaniele Asquini, for a patrol south of the Balearic Islands, between the meridians 02°20′ E and 02°40′ E and the parallels 37°40′ N and 38°10′ N.

October 21st, 1942

At 00.40 AM, 1.40 AM, and 2.50 AM Turchese was sighted several times by the submarine Corallo.

At 11:19 AM Turchese sighted an aircraft at 7,000 meters, in position 37°13′ N and 04°46′ E; and dove to avoid an attack.

October 24th, 1942

At 7.50 AM the boat sighted an aircraft at 5,000 meters, in position 38°06′ N and 02°29′ E; again, it dove.

October 25th, 1942

Another sighting of an aircraft, this time at 1.44 PM in position 37°47′ N and 02°29′ E, from 5,000 meters away. Once again, it dove.

October 28th, 1942

At 9:41 PM, Turchese was informed that a British naval force had left Gibraltar that morning: Force H (aircraft carrier H.M.S. Furious, anti-aircraft cruisers H.M.S. Aurora and H.M.S. Charybdis, destroyers H.M.S. Laforey, H.M.S. Lookout, H.M.S. Bicester, H.M.S. Eskimo, H.M.S. Venomous, and H.M.S. Tartar), engaged in Operation “Baritone”, consisting of the launch of 29 Spitfire V fighters bound for Malta. In addition to Turchese, the submarines Brin, Corallo, Emo, Topazio, and Axum are also directed against it, to form a submarine barrage south of the Balearic Islands.

Turchese moved to the southern end of its patrol sector and went into hydrophone listening, but to no avail. None of the submarines encountered the British units, which moved north of Algiers to carry out the launch and then returned to base.

October 29th, 1942

At 11 AM, the boat received orders from Maricosom to move southwest of Cape Palos, but again there were no sightings.

October 30th, 1942

At 12.52 PM, in position 38°50′ N and 03°16′ E, a steamer was sighted sailing southwards, from 13 km away; Commander Asquini believed that the ship belongs to Vichy France. At 6:00 PM another steamer was sighted heading south, from 11 km away, in position 38°50′ N and 04°02′ E. This was also considered French.

November 1st, 1942

Turchese returned to Trapani at 2.40 PM, after having covered 1823 miles.

November 7th, 1942

Under the command of Lieutenant Giandaniele Asquini, Turchese sailed from Trapani at one o’clock in the morning for a patrol off Bizerte, in position 37°12′ N and 08°00′ E (for another source, 37°30′ N and 10°00′ E, and shortly after 37°20′ N and 07°50′ E), to counter the Anglo-American landings in French North Africa (operation “Torch”). More than 800 British and American ships of all types are sailing towards the coasts of Morocco and Algeria, to land troops to open a second front in North Africa, at the same time as the breakthrough operated by the British Eighth Army in Egypt, at El Alamein.

Supermarina, informed of the sighting of large Anglo-American naval forces sailing westward from Gibraltar, correctly guessed that the Allies probably wanted to attempt a landing in North Africa, although Turchese did not completely exclude the possibility of a convoy heading to Malta.

In total, Maricosom – on the basis of an order from Supermarina, transmitted at 10.06 PM on November 6th – sent twenty-one submarines to the western and central-western Mediterranean, to counter the enemy operation: twelve submarines of the VII Grupsom (Acciaio, Argento, Asteria, Aradam, Brin, Dandolo, Emo, Galatea, Mocenigo, Platino, Porfido, Velella) were deployed west of the island of La Galite (zone “A”), seven submarines of the VIII Grupsom (Bronze, Alagi, Avorio, Corallo, Diaspro, Turchese) were sent north of Bizerte (zone “B”), and two others (Axum and Topazio) in an advanced position between Algeria and the Balearic Islands. These positions turned out to be too far from the actual landing zones (Oran and Algiers), but they were not modified, because the German commanders mistakenly believed that the Allies could attempt further landings in Tunisia as well (in which case the Italian submarines would be in an ideal position).

At 3:31 PM Maricosom (the Submarine Squadron Command) informed all submarines lurking in the western Mediterranean of the position of a British naval squadron and an enemy convoy, reported at 10:40 AM. At 8:07 PM the Submarine Squadron Command reported the position of two convoys sighted on two separate occasions, both heading east and consisting of merchant ships escorted by battleships, aircraft carriers, cruisers, and escort ships.

November 8th, 1942

The landings began: 500 Anglo-American transport ships, escorted by 350 warships of all kinds, land a total of 107,000 soldiers on the coasts of Algeria. Since these operations took place in the areas of Algiers and Oran, the Italian submarines were too far east to intervene. Also, since the German commanders believed that the Allies could make further landings further east, towards Tunisia, it was initially decided to leave the submarines where they were.

At 5:58 PM, north of Bizerte, Turchese sighted a submarine that was identified as the Bronzo. Both boats pulled over to get away, to avoid accidents.

November 9th, 1942

At 7.30 AM, in position 37°18′ N and 08°40′ E, a French ship of 2,000 tons was sighted, from 4,500 meters away.

November 11th, 1942

At 16:45 a submarine was sighted in position 37°08′ N and 07°58′ E and was identified as the Aradam.

November 13th, 1942

At 7:45 AM, an aircraft was sighted in position 37°58′ N and 10°06′ E, 4,000 meters away. Turchese dove to escape an attack; then it headed back to the base, passing through the conventional point T.3. The boat arrived in Cagliari at 9.10 PM, after having covered 741 miles.

November 15th, 1942

Under the command of Lieutenant Giandaniele Asquini, Turchese left Trapani at 3 PM to move to Naples.

November 16th, 1942

Turchese arrived in Naples at 3:55 PM, after traveling 220 miles.

November 25th, 1942

Turchese left Naples at 3.05 PM, under the command of Lieutenant Giandaniele Asquini, to move to La Maddalena.

November 27th, 1942

The boat arrived at La Maddalena at 8.30 AM, after having covered 232 miles.

December 2nd, 1942

Under the command of Lieutenant Giandaniele Asquini, Turchese set sail from La Maddalena at 3.54 AM for a patrol off the coast of Ajaccio, in a sector between the meridian 08°20′ E, the Corsican coast and the parallels 41°40′ N and 41°55′ N.

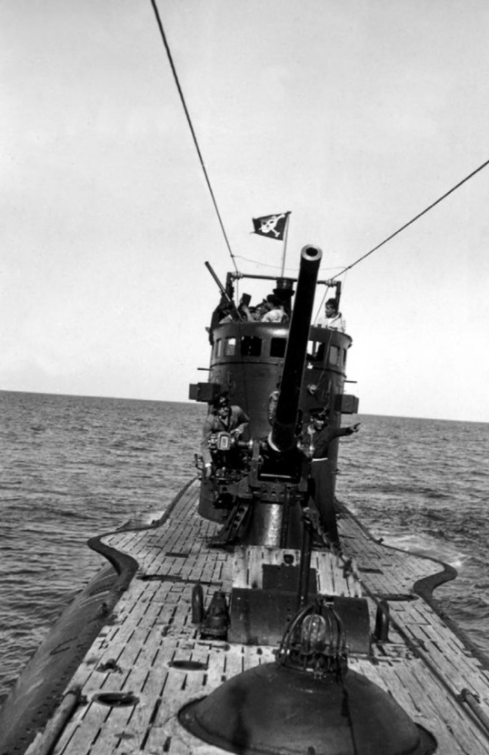

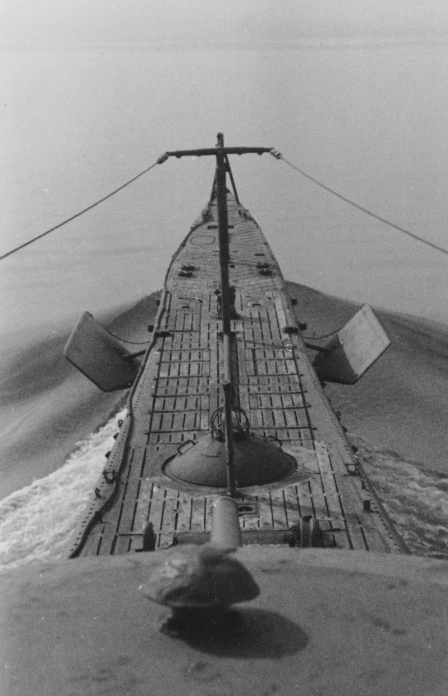

Images taken abord the submarine Turchese during war patrols

(Collection Angelo Ortu)

December 3rd, 1942

At 7:02 AM, Turchese sighted two steamers escorted by a torpedo boat off Cape Senetosa, heading north; However, the torpedo boat was identified as an Italian unit of the “Tre Pipe” type, so no offensive action was taken. At 10.10 PM Turchese returned to La Maddalena after having covered 262 miles.

December 6th, 1942

Under the command of Lieutenant Giandaniele Asquini, Turchese left La Maddalena at 6.15 PM to move to Cagliari, together with Diaspro and Corallo.

December 7th, 1942

Turchese arrived in Cagliari at 2.40 PM, after having covered 191 miles.

December 9th, 1942

Turchese set sail from Cagliari at 6:00 PM, under the command of Lieutenant Giandaniele Asquini, for a patrol off the Algerian coast, in the area between meridians 08°20′ E and 08°40′ E and parallels 37°40′ N and 38°00′ N. At 9.45 PM the submarine Galatea was encountered, returning to base, with which the recognition signals were exchanged. Shortly thereafter, Turchese had to turn around to return to base due to engine problems.

December 10th, 1942

Turchese arrived in Cagliari at 12.08 pm, after having covered 86 miles.

December 22nd, 1942

Departure from Cagliari for exercise, from 8.27 AM to 11.27 AN, under the command of Lieutenant Giandaniele Asquini travelling 22 miles.

December 29th, 1942

Turchese left Cagliari at 12.50 PM, under the command of Lieutenant Giandaniele Asquini, to move to Augusta. While sailing, the crew herard bomb explosions in the distance.

December 31st, 1942

Turchese arrived in Augusta at 3:40 PM, having covered 481 miles.

January 4th, 1943

Turchese set sail from Augusta at 3.37 AM, under the command of Lieutenant Giandaniele Asquini, for a patrol southwest of Malta. At 3:52 AM, however, while leaving the harbor in the dark and in poor visibility conditions, Turchese crashed into one of the base’s anti-torpedo obstructions, sustaining such damage that it had to turn back, mooring at Augusta at 8:43 AM after traveling 30 miles. Commander Asquini received a reprimand for what happened, while the navigational officer would be severely punished.

January 5th, 1943

Turchese left Augusta at 5.15 PM, under the command of Lieutenant Giandaniele Asquini, to move to Messina.

January 6th, 1943

The boat arrived in Messina at 8.15 AM, after covering 74 miles.

January 11, 1943

Turchese left Messina at 6.34 AM, still under the command of Lieutenant Asquini, to return to Augusta, where it arrived at 1.41 PM, after having covered 73 miles.

January 17th, 1943

Turchese sailed from Augusta at 9:55 PM to patrol an area between the meridians 21°00′ E and 21°30′ E, the parallel 34°00′ N and the Libyan coast.

January 20th, 1943

At 5:00 PM, before reaching the sector assigned for the mission, the boat received orders to return to base.

January 22nd, 1943

Turchese arrived in Augusta at 7:11 AM, having covered 704 miles.

February 7th, 1943

Turchese set sail from Augusta at 4.20 PM, under the command of Lieutenant Asquini, for a patrol off Cape Misrata, between the meridians 15°20′ E and 15°40′ E and the parallels 32°40′ N and 33°30′ N.

February 14th, 1943

Turchese was ordered to move to a new patrol area, between the meridians 15°50′ E and 16°40′ E and the parallels 32°00′ N and 32°10′ N (for another source, between 32°20′ N and 32°30′ N and between 15°00′ E and 18°00′ E).

February 16th, 1943

At 3:56 AM, Turchese received a signal of discovery of a convoy, launched from Axum. The boat changed course to 120° to intercept it, but it did not spot anything.

February 21st, 1943

The boat returned to Augusta at 9:50 AM, after having covered 1,395 miles.

February 26th, 1943

Turchese set sail from Augusta at 4:00 PM, under the command of Lieutenant Asquini, to move to Taranto, where he had to undergo a period of refitting.

February 28th, 1943

The boat arrived in Taranto at midnight, after having traveled 297 miles, and entered the shipyard.

April 20th, 1943

Once work was completed, Turchese left Taranto for sea trials from 1:00 PM to 6.30 PM, again under the command of Lieutenant Asquini, covering 8 miles.

April 22nd, 1943

Departure from Taranto for sea trials from 6:00 AM to 5.15 PM, under the command of Lieutenant Asquini travelling 38.5 miles.

April 24th, 1943

Departure from Taranto for sea trials from 2.20 PM to 6.30 PM, under the command of Lieutenant Asquini navigating 2 miles.

April 26th, 1943

Departure from Taranto for sea trials from 6.30 AM to 2.10 PM, under the command of Lieutenant Asquini travelling 27 miles.

April 27th, 1943

Departure from Taranto for sea trials from 7.35 AM to 1.40 PM, under the command of Lieutenant Asquini travelling 24.5 miles.

April 28th, 1943

Departure from Taranto for sea trials from 11.46 AM to 5.33 PM, under the command of Lieutenant Asquini, together with the tugboat Gagliardo and with the escort of the auxiliary ship Claretta travelling 20 miles.

April 29th, 1943

Departure from Taranto for sea trials from 5.40 AM to 10.40 AM, under the command of Lieutenant Asquini travelling 21 miles.

April 30th, 1943

Lieutenant Asquini handed over command of Turchese to Aredio Galzigna, 29, from Šibenik.

May 2nd, 1943

Departure from Taranto for sea trials from 12.05 PM to 7.40 PM, under the command of Lieutenant Aredio Galzigna travelling 27 miles.

May 3rd, 1943

Departure from Taranto for sea trials from 12.45 PM to 6.50 PM, under the command of Lieutenant Aredio Galzigna travelling 23 miles.

May 6th, 1943

Departure from Taranto for sea trials from 11.35 AM to 19.45 nAM, under the command of Lieutenant Aredio Galzigna travelling 34.5 miles.

May 8th, 1943

Departure from Taranto from 11.35 AM to 5.30 PM, under the command of Lieutenant Aredio Galzigna, for sea trials together with the gunboat-submarine destroyer Vergada travelling 21.5 miles.

May 10th, 1943

Departure from Taranto for sea trials from 11.40 AM to 6.24 PM, under the command of Lieutenant Aredio Galzigna travelling 28 miles.

May 11th, 1943

Departure from Taranto for sea trials from 7.05 AM to 7.05 PM, under the command of Lieutenant Aredio Galzigna travelling 32 miles.

May 12th, 1943

Commander Carlo Liannazza, commander of the IV Submarine Group, recommends extending the training period of Turchese, since four of the five officers had recently assigned to the boat, and Commander Galzigna was on his first command.

May 15th, 1943

Departure from Taranto for sea trials from 3.35 PM to 1.05 AM on the 16th, under the command of Lieutenant Aredio Galzigna covering 34.5 miles.

May 17th, 1943

Departure from Taranto for sonar sea trials from 6.30 AM to 11.20 AM, under the command of Lieutenant Aredio Galzigna, together with the torpedo boat Monzambano and the corvette Gabbiano travelling 27.5 miles.

May 20th, 1943

Turchese left Taranto at 6:46 PM, under the command of Lieutenant Aredio Galzigna, to move to Naples.

May 25th, 1943

At 11:35 AM the boat sighted a formation of four-engine bombers flying eastwards, in the Strait of Messina, and dove to avoid them. The planes spotted it and attacked it while it was submerged, forcing it to zigzag at top speed as several bombs fell into the sea about 900 meters aft.

Back on the surface, at 12:09 PM it sighted another formation of four-engine planes flying eastwards. Again, it dove with a crash dive to a depth of 70 meters, while several explosions of depth charges were heard in the distance.

Returning once again to the surface, at 1.34 PM Turchese sighted a third group of four-engine aircraft, this time flying southwards. Again, it dove precipitously, hearing the explosions of nearby bombs (but probably not directed at it) at 1:38 PM and 1:40 PM

May 27th, 1943

Turchese finally arrived in Naples at 6:45 AM, after traveling 644 miles. At 11.32 AM left for Pozzuoli, where it arrived at 12.50 PM, after having covered 8 miles.

May 29th, 1943

Departure from Pozzuoli for sea trials, from 11:00 AM to 3.30 PM, under the command of Lieutenant Aredio Galzigna travelling eleven miles.

May 30th, 1943

Turchese left Pozzuoli at 9.30 AM, under the command of Lieutenant Aredio Galzigna, to move to Naples, where he arrived at 11.10 AM, after having covered 8 miles.

June 1st, 1943

Turchese left Naples at 5.30 PM under the command of Lieutenant Aredio Galzigna, for an exercise.

June 2nd, 1943

At the end of the exercise, Turchese returned to Naples at 5.50 AM, after having covered 42 miles. The boat left at 9.35 AM to move to Pozzuoli, where it arrived at 11:00 AM, after having covered 8 miles.

June 3rd, 1943

Departure from Pozzuoli for exercises and tests, from 9.03 AM to 3.53 PM, under the command of Lieutenant Aredio Galzigna travelling 18 miles.

June 4th, 1943

Departure from Pozzuoli for exercises and tests, from 2.05 PM to 5.56 PM, under the command of Lieutenant Aredio Galzigna travelling 18 miles.

June 16th, 1943

Departure from Pozzuoli for exercises and tests, from 4.23 AM to 12.16 PM and from 5.15 PM to 9.20 PM, under the command of Lieutenant Aredio Galzigna covering32 miles in the morning, and 30.5 in the evening.

June 17th, 1943

E Departure xit from Pozzuoli for exercises and tests, from 2.15 PM to 6.45 PM, under the command of Lieutenant Aredio Galzigna travelling 15 miles.

June 18th, 1943

Departure from Pozzuoli for exercises and tests, from 8.34 AM to 12.05 PM, under the command of Lieutenant Aredio Galzigna travelling 18 miles.

June 19th, 1943

Departure from Pozzuoli for exercises and tests, from 8.20 AM to 10.05 AM and from 7.05 PM to 3.05 AM on June 20th, under the command of Lieutenant Aredio Galzigna covering8 miles in the morning, and 34 in the evening.

June 23th, 1943

Departure from Pozzuoli for exercises and tests, from 11.13 AM to 12.30 PM, under the command of Lieutenant Aredio Galzigna covering 8 miles. At 11.01 PM Turchese left Pozzuoli to move to La Maddalena.

June 26th, 1943

Turchese arrived at La Maddalena at 6.40 AM, after having covered 312 miles, and left at 9.15 AM to move to Santo Stefano, where it arrived at 10.16 AM, after another 4 miles.

June 28th, 1943

The boat left Santo Stefano at 4:57 PM, under the command of Lieutenant Galzigna, to move to Bonifacio, where it arrived at 7:45 PM, after having traveled 21 miles.

June 30th, 1943

Under the command of Lieutenant Galzigna, Turchese sailed from Bonifacio at 10.36 PM for a patrol southwest of Sardinia, between meridians 07°00′ E and 07°40′ E and between parallels 38°00′ N and 38°40′ N.

July 1st, 1943

At 9:15 AM, in position 38°20′ N and 07°28′ E, a large air formation was sighted flying eastwards and the submarine dove to avoid being attacked.

July 2nd, 1943

At 7:58 PM Turchese received orders to go up to the parallel 37°20′ N, between 36°40′ N and 07°40′ E, and then return to the previously assigned sector.

July 6th, 1943

At 12:55 PM Turchese received orders to move 10 miles to the east, and then to reach the parallel 37°50′ N by dawn on the 7th. It then moved westwards, from meridian 08°10′ E to that of Cap de Fer (07°10′ E) on the parallel 37°20′ N, a transfer that took place late due to engine problems, and then returned to the original ambush area at dawn on the 8th.

The assignment was to form a preventive barrage to the south of Sardinia, in contrast to a possible Anglo-American landing (which will then take place in Sicily), together with Giada, Alagi, Argento, Nereide, Nichelio, Platino, and Diaspro.

July 10th, 1943

At 2:15 AM Turchese received the order, issued at 00:15 AM, to execute the “Zeta” plan and reach quadrant 96. At 2:25 PM the boat received a new message, transmitted at 11:41 AM, ordering it to reach zone 172 immediately.

July 11th, 1943

At 00.13 Turchese received an order (transmitted at 10.13 PM the previous evening) to reach zone 83 (east coast of Sicily) passing through point 39°00′ N and 15°00′ E and through the conventional point M 3 (off Capo Vaticano).

At 5:22 AM the boat sighted a twin-engine aircraft flying at low altitude with a south-easterly course, in position 38°20′ N and 09°25′ E, and dovew as a precaution. Back on the surface, at 9.08 AM (in 38°20′ N and 09°25′ E) the crew sighted another plane flying southwards. Again, Turchese submerged; at 8.22 PM (position 38°24′ N and 10°10′ E) a third aircraft was sighted flying southeastwards, and once again the boat dove.

At 9:10 PM, yet another new order was received, transmitted at 6:40 PM to move to zone 81; but at 9.32 the yet another plane was sighted, flying northwestwards, in position 38°25′ N and 10°12′ E, and Turchese dove yet another time.

July 12th, 1943

At 4:28 AM, in position 38°43′ N and 11°35′ E, another plane was sighted: another dive, repeated at 10:50 AM following the sighting of a second aircraft with a westerly course.

July 13th, 1943

Yet another sighting of an aircraft, at 3.50 AM, in position 38°48′ N and 12°30′ E: again, Turchese had to dive.

July 14th, 1943

At 00:07 Turchese received orders from Maricosom to move to the northern half of quadrant 80 but had to abandon the mission due to a breakdown. At 5.13 AM the boat dove following the sighting of an aircraft in position 39°00′ N and 13°20′ E.

July 16th, 1943

The boat arrived in Naples at 6.45 AM, after having covered 1,300.5 miles. At 11.05 AM it left to move to Castellammare di Stabia, where it arrived at 12.50 PM, after having covered 13.3 miles.

July 30rd, 1943

Departure from Castellammare di Stabia for sea trials, from 7.20 AM to 10.15 Am travelling 10 miles. At 8.47 PM, still under the command of Lieutenant Galzigna, the boat left Castellammare to move to La Maddalena.

July 31st, 1943

At 2:20 AM, flares were sighted about 2,000 meters away; Turchese dove as a precautionary measure.

August 2nd, 1943

Turchese arrived in La Maddalena at 7.20 AM, after having covered 257 miles, and left at 12.15 PM to move to Mezzoschifo, where he arrived at 1.55 PM, after another 2 miles.

August 3rd, 1943

Turchese left Mezzoschifo at 4.34 AM, under the command of Lieutenant Galzigna, to move to Bonifacio, where he arrived at 7.25 AM, after having covered 19 miles.

August 19th, 1943

Departure from Bonifacio for sea trials from 7.29 AM to 11.40 AM, under the command of Lieutenant Galzigna travelling 22.5 miles.

August 21st, 1943

Lieutenant Galzigna was replaced in command of Turchese by Eugenio Parodi, 26, from La Spezia.

August 24th, 1943

Departure from Bonifacio for sea trials from 7.25 AM to 11.59 AM, under the command of Lieutenant Eugenio Parodi travelling 26 miles.

August 27th, 1943

Departure from Bonifacio for sea trials from 7.36 AM to 12.22 PM, under the command of Lieutenant Parodi travelling 27.5 miles.

August 31st, 1943

Departure from Bonifacio for sea trials from 7.47 AM to 12.30 PM, under the command of Lieutenant Parodi travelling 24 miles.

September 2nd, 1943

Turchese sailed from Bonifacio at 5.20 AM, under the command of Lieutenant Eugenio Parodi, to move to Villa Marina (on the island of Santo Stefano), where it arrived at 7.59 AM, after traveling 24 miles.

September 7th, 1943

At 3.15 PM (or 1.15 PM) Turchese (Lieutenant Eugenio Parodi) set sail from Villa Marina together with the similar submarine Topazio, for a patrol in the gulfs of Paola and Gaeta. Both submarines, together with Diaspro and Marea, were to form a barrage in the Gulf of Salerno, in contrast to the imminent Anglo-American landing (operation “Avalanche”). Eight other submarines (Brin, Giada, Galatea, Platino, Nichelio, Alagi, Axum, and Velella) complete the anti-landing screen in the Lower Tyrrhenian Sea, along the Tyrrhenian coasts of Campania and Calabria between Paola and Gaeta, while ten (Onice, Settembrini, Vortece, Zoea, Bragadin, Squalo, Menotti, Bandiera, Jalea, and Manara) were deployed in the Ionian Sea along the eastern coasts of Sicily and Calabria. All executed within the framework of the “Zeta” Plan: Supermarina ordered its activation by Maricosom following the sighting in the Lower Tyrrhenian Sea by German air reconnaissance, on the evening of September 7th, of the Allied landing fleet heading towards Salerno.

At 4 PM, off the coast of La Maddalena, Turchese was accidentally targeted by a coastal battery, which fired three salvos without hitting; The shots fell short of about 200 meters.

September 8th, 1943

The armistice between Italy and the Allies was announced: Maricosom ordered all submarines to cease hostilities, immediately dive to a depth of 80 meters and resurface at eight o’clock in the morning of September 9th, and then remain on the surface flying the Italian flag and a black pennant on the periscope, waiting for further instructions. Subsequently, the order was given to head towards Bona, Algeria (for submarines lurking east of Sicily, towards other ports under Allied control such as Malta, Brindisi, and Augusta), keeping the signs of recognition clearly visible.

September 9th, 1943

Interrupted the mission as ordered, Turchese moved from its ambush position south of Sardinia, at 12.21 meeting Topazio (lieutenant Pier Vittorio Casarini) and Marea (sub-lieutenant Attilio Russo), and shortly afterwards the Diaspro (lieutenant Alberto Donato) to form a group. The respective commanders began “discussing” the situation by means of light signals made with the small flashes of light projectors supplied to each submarine (for another version, the “discussion” between the commanders would have taken place by means of megaphones, from their respective cunning towers, given the short distance).

Later, all four of them gather aboard the Diaspro to decide what to do. There are conflicting versions of the outcome of this meeting: according to various authors (including Achille Rastelli and Giuliano Manzari) this first meeting was followed by others on the mornings of September 10th and 11th, and in the end each of the commanders made a different decision. Marea to sail for Bona, Diaspro for Cagliari (assuming there were no German troops), Topazio to the north and Turchese to reach neutral Spain, more precisely the Balearic Islands (which, however, was not confirmed by Turchese’s report, according to which the submarine initially headed towards the 42nd parallel and then towards Bona).

According to the Marea’s report, however, at the end of the meeting the four commanders decided by mutual agreement to aim for Bona, sailing together and waiting for other submarines; the four submarines remained reunited or at least in sight of each other until the evening of the 10th (according to the Marea report, however, the latter and the Diaspro lost sight of Turchese and Topazio as early as 10.30 PM on the 9th, and then lost sight of each other as well). From ten o’clock on September 9th, Turchese sails towards the 42nd parallel.

September 10th, 1943

Turchese and Topazio separated at the Anzio parallel, slightly east of the 11° E parallel. At eight o’clock in the morning, Commander Parodi decided to go directly to Bona.

September 11th, 1943

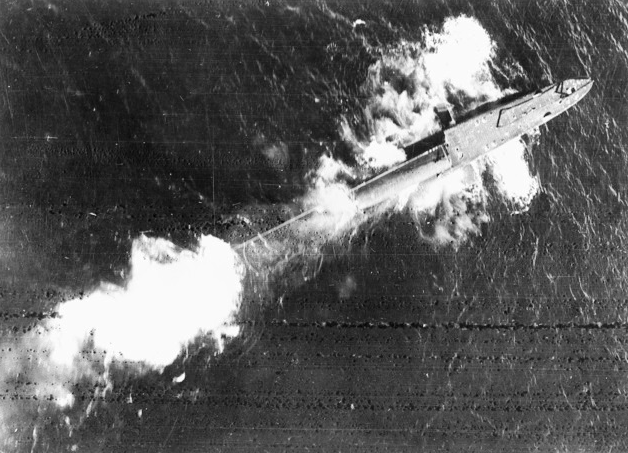

At 9:27 PM, Turchese was attacked off Bona by an aircraft that was identified as a German Junkers Ju 88 bomber. The bombs that fell closer ended up in the water 6 meters from the bow, portside, exploding underwater at a depth of 10 meters. The explosions cause serious damage to the submarine, knocking out the left diesel engine (for another version, both engines, making it impossible to continue navigation).

The attacking aircraft was not German, but British: a Lockheed Hudson bomber of the 500th Squadron of the Royal Air Force, the “O” aircraft of Second Lieutenant G. M. Shires. Sighting the submarine, and doubtful of its nationality, Lieutenant Shires flew over it twice circling, throwing on the second lap the colors agreed for that day as a signal of recognition. Having received no response, he went on the attack, aiming at the submarine from the opposite direction to that of the Moon (from the starboard bow) and launching a salvo of four depth charges, which fell into the sea astride the cunning tower (according to a source, while the submarine was diving). After the attack, Lieutenant Shires watched the submarine dive astern. Half an hour later, he received orders from the base not to attack unless the boat took hostile action.

September 12th, 1943

In the late afternoon, Turchese encounters a British convoy and was taken in tow by the British armed trawler Stroma.

September 13th, 1943

The damaged Turchese reached Bona at 00:02, in tow of the Stroma, after covering 695 miles. The misunderstanding of which Turchese was the victim extends, with tragic consequences, to Topazio as well. Turchese, in fact, was not the only Italian submarine to be mistakenly attacked by British planes: on the morning of September 12th, Topazio, mistaken by a Bristol Blenheim for a German U-boat, was bombed, and sunk by the latter south of Sardinia.

Most of the crew, fifteen or twenty men, survived the sinking: the British Commands initially sent air and naval vessels to the site to recover them, but recalled them following the news that Turchese had been damaged by an air attack and was sailing towards Bona, mistakenly believing that the submarine attacked by the Blenheim was indeed Turchese. and that the pilot’s assertion that he sank it was the result of a mistaken appreciation. The result of this incredible sequence of errors and misunderstandings will be that no one will come to the rescue of the castaways of the Topazio, of which there will be, consequently, no survivor.

September 14th, 1943

Still under the command of Lieutenant Eugenio Parodi, Turchese sailed from Bona at 1.30 PM to Malta, in tow of the submarine Marea and together with the submarines Alagi, Giada, Galatea, Brin, Menotti and Platino, which converged in Bona following the armistice. The group was escorted by the British destroyer H.M.S. Isis.

A few hours after the departure, however, the tow cable snapped, and Turchese had to be towed back to Bona by a British ship, arriving there at 10:00 PM, after having traveled thirty miles. It then remained under repair in Bona, where the work was completed on September 24th.

September 27th, 1943

Turchese left Bona at 5.21 PM, still under the command of Lieutenant Parodi, to move to Malta. After a few hours, however, the engines failed, which forced the boat to be towed back to port.

September 28th, 1943

Turchese returned to Bona at 7.30 AM, after covering 59 miles, in tow of a British unit.

October 1st, 1943

Turchese left Bona in tow at 4.30 PM, to move to Bizerte. The commander was still Lieutenant Parodi.

October 2nd, 1943

The boat arrived in Bizerte at 5:15 PM, after traveling 123 miles.

October 4th, 1943

The boat left Bizerte at 11.30 AM, under the command of Lieutenant Parodi, for the third attempt to move to Malta. This time it was in tow of the British armed trawler Goth, together with the harbor tug C.T. 13, the motor launches ML 480 and HDML 1243 and the armed fishing vessel HMS Tango, in a convoy of three merchant vessels.

October 6th, 1943

Turchese, finally, arrived in Malta at 10.30 AM, after having covered 251 miles. It was the twenty-third and last Italian submarine to reach the island after the armistice. Turchese went to moor in Marsa Scirocco, under the command of the battleship Giulio Cesare, joining the submarines Atropo, Axum, Bandiera, Bragadin, Corridoni, Giada, Marea, Nichelio, Settembrini and Vortece, moored there since September.

November 27th, 1943

Still under the command of Lieutenant Parodi, and once again in tow (this time, of the corvette Chimera), Turchese left Malta at 3.30 PM to return to Italy. It was the last Italian submarine to leave the island. On the same date, the second chief torpedoman Giuseppe Da Rold, 22 years old, from Belluno, died in the metropolitan area.

November 28, 1943

Turchese arrived in Augusta at 9:30 AM, after traveling 117 miles.

December 11th, 1943

Lieutenant Parodi was replaced by Second Lieutenant Giorgio Mogni, 28, from Savignano Irpino.

March 11, 1944

Under the command of sub-lieutenant Giorgio Mogni, Turchese left Augusta in tow of the torpedo boat Monzambano to move to Brindisi.

March 12th, 1944

Turchese arrived in Brindisi at 7.45 PM, after covering 335 miles. There it entered the shipyard for long renovation work (according to another source, it was laid up there).

March 31st, 1944

Sub-lieutenant Mogni was replaced by Lieutenant Commander Renato Frascolla, 33, from Taranto.

September 13th, 1944

Lieutenant Commander Frascolla was replaced by Marco Revedin, 33 years old, from Bologna.

Lieutenant Commander Marco Revedin

(Collection Giovanni Pinna)

November 22nd, 1944

Lieutenant Commander Revedin handed over command of Turchese to Lieutenant Emilio Botta, 26, from Foggia, who held it until the following August.

June 22nd, 1945

Turchese left Brindisi at 6.05 AM, under the command of Lieutenant Emilio Botta, to move to Naples.

June 23rd, 1945

Turchese arrived in Naples at eight o’clock in the morning, after having covered 450 miles. It then remained in the reserve until the end of hostilities.

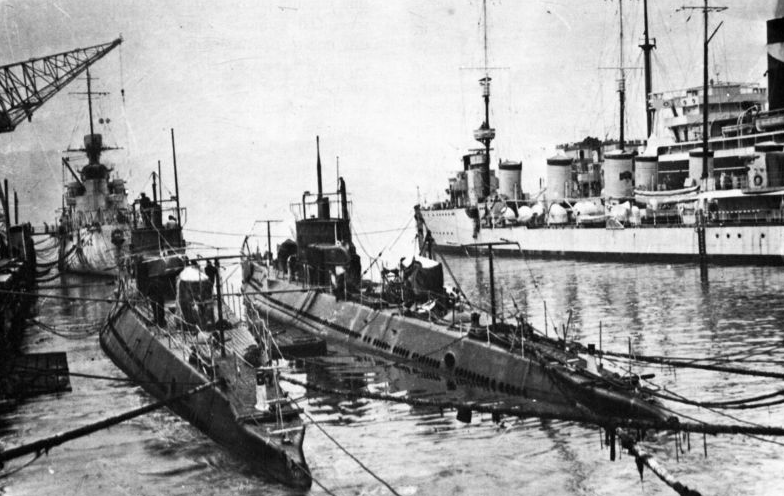

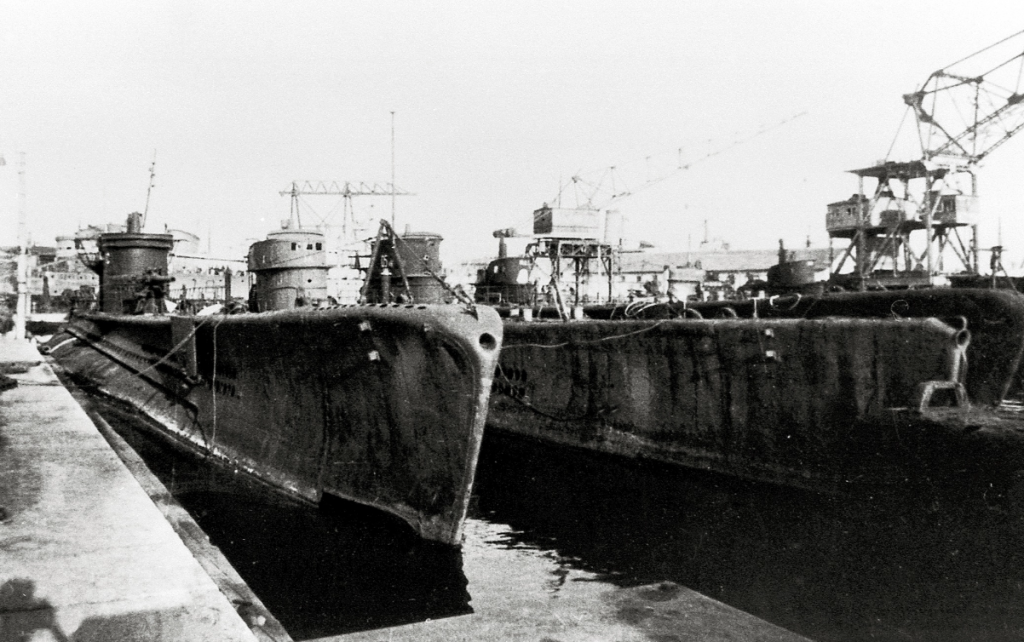

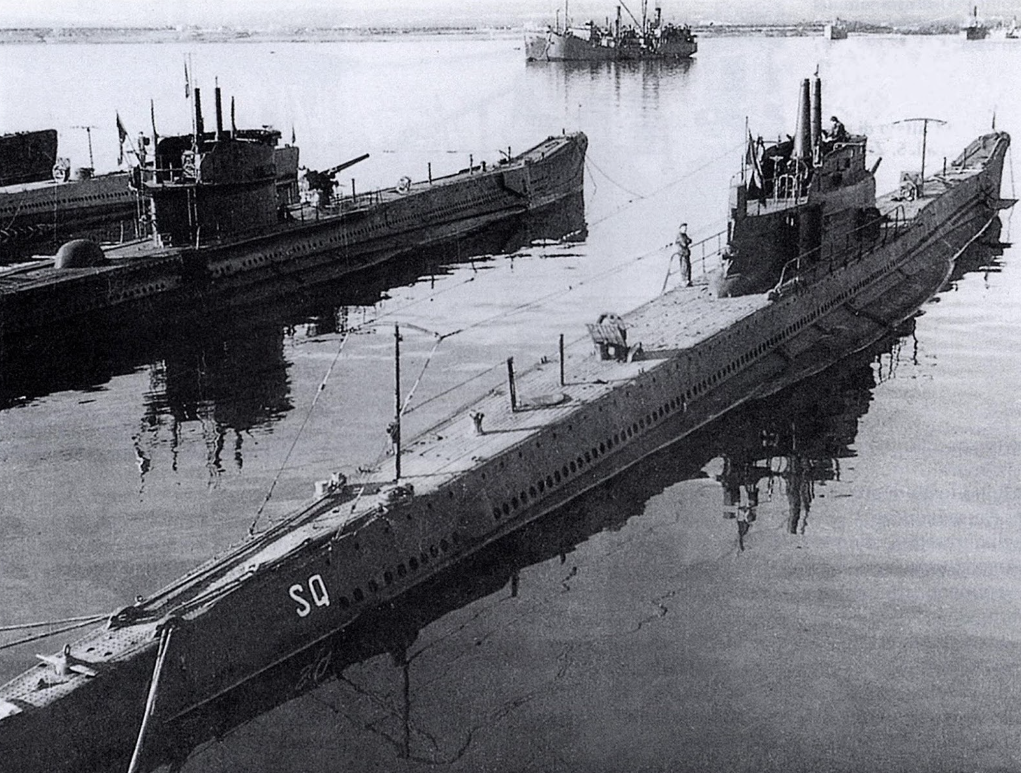

Turchese (in the background) in disarmament in Taranto in an image taken on February 27th, 1947. In the foreground the oceaning submarine Ammiraglio Cagni, in the third row the Galatea

(From “In guerra sul mare” by Erminio Bagnasco)

February 1st, 1948

Turchese was removed from the Navy rosters, as for the peace treaty requirements, and later demolished.

Another image of the remains of Italian submarines decommissioned in Taranto in February 1947: Turchese is at the far right, in the dock overlooking the Caserma Farinati (Farinati Barracks)

(STORIA militare)