The history of the Italian aircraft carriers is one of delayed decisions and postponed opportunities, confrontations, more or less transparent, between the Marina and the Aeronautica, and project after project, none of which was ever realized until the introduction of the Giuseppe Garibaldi in 1985.

World War I and the Birth of the Regia Aeronautica

The first Italian vessel classifiable in any possible way as an aircraft carrier had already entered service during World War I. This was the hydroplane tender Europa, which was the result of the conversion of the merchant ship Quarto, acquired from a German ship owner in 1915, and designed to provide a greater range for reconnaissance and a higher speed than naval units. The alterations to this ship consisted of two hangers built on the bow and stern capable of hosting 8 seaplanes. The ship was not equipped with any machinery capable of launching the planes, which therefore had to be lowered into the water before they could take off. The official classification for this ship was “hydroplanes and submarines support ship”.

The experience of World War I, however, did not convince the higher ranks of the Regia Marina of the usefulness and convenience of inserting one or more aircraft carriers in the order of battle. Several factors influenced this situation, which would drag on until World War II:

The Italian war experience, from a naval viewpoint, was substantially limited to the Adriatic Sea with its short distances, which did not create the need for naval units such as the aircraft carrier.

The institution, in 1922, of the Regia Aeronautica as an independent armed force under the auspices of the fascist Regime, which surely did not assist in any way the process, especially after a rivalry between the two branches became, over time, quite fierce. The Regime’s support for the Aeronautica influenced the process quite heavily, thus eliminating much needed deep and productive collaboration.

The substantial opposition, manifested by the Regime, against the construction of aircraft carriers, despite the many studies and projects (as we will later see), due to the support clearly shown for the Aeronautica, the most “fascist” of all armed forces, to the detriment of the Regia Marina. Also, another consideration was the geographical conformation of Italy, which, it was said, was a natural aircraft carrier stretched out into the Mediterranean thus making the construction of carriers useless.

This last point deserves some further clarification because, under certain conditions, it could have been accepted. The geographical position of the Italian peninsula is effectively very centrally located within the Mediterranean, thus allowing the control of this sea and, if necessary, its separation into two isolated halves. This would have been possible thanks to airports in Sicily and Sardinia which could easily control the areas adjacent to the Western Mediterranean and the access to the Sicilian Channel which is the narrowing which divides the two halves. A similar case could have been made for the eastern part of the Mediterranean, which could be controlled from airports in the Apulie region, and partially from Sicily. If one also considers the Italian control over the Aegean Sea from the Dodecannes island, one might realized that the whole theory was not too far fetched, at least from a geographical viewpoint.

Rota’s project in 1925

Naturally, an argument so presented is only half of one. In fact, to implement what was just said, there are several prerequisites which had to be met and which, as we shall see, were far from being so at the beginning of the hostilities. Foremost, it was necessary to have airplanes with technical specifications commensurate to the requirements for operations at sea. These are long range reconnaissance missions, including scouting and anti-submarine patrol in addition to “classic” attacks against naval targets.

These requirements, in essence, called for the construction of bombers, torpedo bombers, long range reconnaissance planes, and hydroplanes with adequate endurance and defensive armament. It also required fighter planes capable of long escort missions at sea. In essence, it was necessary to build a series of new planes whose foremost characteristic should have been endurance thus allowing for the greatest possible range of action. Instead, the best planes available at the moment were to be utilized, and this does not mean that the aircraft in question were of lesser quality; one only has to see the results obtained by converting the SM-79 to a torpedo bomber.

Another indispensable prerequisite was the creation of an inter-force command center between the Regia Marina and the Regia Aeronautica which would allow, through the implementation of operational procedure and a similar communication system, the expeditious transfer of information and orders thus eliminating delays between the request from the Commander at Sea and the arrival of the air forces sent in his support. This would have allowed the intervention of the air force, within the limits dictated by distance between the fleet and the air bases, in an efficient and timely manner each time a request was generated by the fleet.

Even this aspect was completely neglected. Anything capable of flying was under the direct control of the Regia Aeronautica with the only exception of the hydroplanes INAM Ro-43 aboard battleships and cruisers whose crews were anyway mixed, with the pilot belonging the Aeronautica and the Navigator to the Marina. Naturally, these small single engine byplanes, slow and almost without any armament and with limited endurance were only used for strategic reconnaissance and could not be a substitute for a well trained and coordinated naval aviation unless one or more carriers had been introduced. The consequences were clearly seen at the battle of Punta Stilo, where about one hundred bombers sent to the battle arrived late. Some of them even attacked the Italian ships, mistake this probably justified by the intense anti aircraft barrage generated by the fleet and which, thankfully, did not have any positive effect.

In conclusion, the few squadrons placed here and there, should have been instead a much more robust air force, probably with a few hundreds planes of various kind strategically placed in different sectors but with forces sufficient for a massive deployment. Ultimately, none of this was ever accomplished: the Regia Marina had to operate without aircraft carriers and without an air force trained and available. During the conflict, the occasions in which collaboration between the Regia Marina and the Regia Aeronautica worked decently could be counted on a single hand. Let us go back to the aircraft carries:

The Projects

Notwithstanding the evident opposition of the regime to the construction of aircraft carriers, the Regia Marina dedicated resources in support of studies and projects for the entire period preceding the conflict. Specifically, three projects from this period deserve mentioning for the thoroughness of the studies conducted. These projects were presented in 1925, 1928 and 1932 with the last one reintroduced in 1936 after a few variances.

In reality, even since 1921, Lieutenant G. Fioravanzo had presented a project for an hybrid called “antiaircraft cruiser” which was born of the idea of merging on a single naval platform antiaircraft guns and a group of fighter planes. This ship, similar in dimension to the British Hermes, was to displace 10,000 tons and produce a speed of 30 knots while armed with 18 102mm guns of 16 120mm ones. The fighter group was to be composed of 16 fighter planes.

The first project, dating back to 1925, presented a hybrid of about 12,500 tons, half carrier and half cruiser. The landing deck was to be of full length, still leaving enough space at the two extremities for two quadruple 203mm turrets to be used against other ships. These would be complemented by 6 100mm installed on island to the side of the deck and two six-gun 40mm place on the bow and stern. The stern was configured like a slide, thus allowing the deployment and retrieval of reconnaissance hydroplanes of which the ship was to be equipped. In the middle of the landing deck were to be placed the fire control towers along with the three funnels and the mast. These apparatuses were retractable, thus allowing for the entire landing deck to be used for flight operations. The funnels, while retracted, was to discharge through a lateral opening.

In 1928, the same project was updated increasing the displacement to 15,000 tons (thus allowing for a better utilization of the 60,000 tons allotted to Italy by the conference of Washington) and with speed similar to the larger units (battleships and cruisers) then in use. Armament was to be composed by 6 dual 152mm guns and 8 dual 100 mm ones for antiaircraft defense. For armor, the horizontal protection was to be similar to the Trento class, while for the vertical it was planned to have reinforced plates protecting the vital parts of the ship (engines, ammunition depots and gasoline). The air wing was planned at 40 aircraft: 18 fighters, 12 reconnaissance planes and 6 to 12 attack planes. But, as a document from the time says, “the need for this type of ship has not yet been recognized by His Excellency the Minister…”.

The 1932 project called for unit much more conventional of about 15 to 16,000 tons with a full flight deck and an “island” to starboard more toward the bow. Armament, much more adapted for a carrier, was to be constituted by 4 152mm guns and 7 102mm ones and a wing of about 40 to 45 planes. The 1936 project represented and improvement over the preceding one, with displacement around 15,000 tons and armament constituted by three triple 152mm guns in front and behind the “island” and with a large number of anti-aircraft 90mm guns. The wing was to be constituted by 42 planes: 24 fighters and 18 diving bombers-reconnaissance deployable my means of two or three catapults. Armor was to be light, only 60 mm near the most vital parts near the center of the ship and possible near the bow. There was not to be any horizontal protection, impossible to implement which such limiting displacement.

Instead, the ship was to be equipped with underwater protection made out of multiple bulkheads 3 meters apart and creating a second hull, which should have been untouched by eventual damages. The engine was to produces a very high 160,000 HP generating a maximum speed of 38 knots (!). Speed this that was thought necessary for the ship to be effective. However, many noted that if the required speed had bee reasonably kept to 32 knows, the HP requirement would have been cut in half. Hsis would have created less stress on the engine itself, leaving more room for the aeronautical infrastructures, such has hangars, shops, ammo and fuel depot ultimately increasing the operational life of the vessel.

Furthermore, it would have been possible to utilize a diesel engine with the well-known advantages in terms of fuel consumption, reliability and longevity. Regardless, despite the blooming of projects and the favorable opinions expressed by high ranking officers of the Regia Marina, none of these projects ever materialized and the Regia Marina found itself on June 10th, 1940 without an aircraft carrier and, as a matter of fact, without naval aviation.

The war, Matapan and the Aquila

Under these circumstances, all problems came immediately to the surface and, already during the Action of Calabria, it was understood the significance of requesting assistance from land-based wings without any established procedure in regards to shared command and control. If this had not been enough, the Battle of Gavdo and Matapan took care of clearing out, one and for all, any doubt about the usefulness of the aircraft carrier as part of a battle group.

The destruction of three heavy cruisers and their escort by the Mediterranean Fleet was possible thanks to the presence of the radar on the British units. Also instrumental was the timely and meticulous British reconnaissance which kept Admiral Cunnigham always informed of the position and situation of the Italian fleet. Furthermore, the presence of the Formidable allowed for the deployment of a group of torpedo bombers, which, the night of the 28th of March, was able to immobilize the Pola with all the terrible consequences which followed.

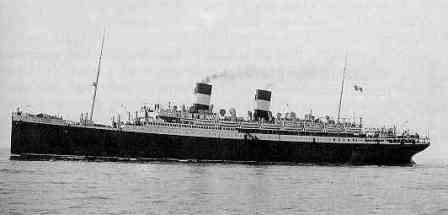

The liner Roma

After that terrible day, there was not any hesitation: the Regia Marina had to have an aircraft carrier. In July, the order was given for the conversion of the liner Roma to an aircraft carrier. This liner was chosen in virtues of several factors, which made it a better candidate that other ships. First of all, it was not too old (it was about 15 year old) but still it needed work to remain competitive in its arena, so the ship owner would not create too many difficulties in giving up the vessel. Second, most of the internal structure needed upgrading and it was therefor convenient to do it as part of the transformation. Also, the engine was not any longer adequate and needed work. The hull, on the other hand, was strong and spacious and would have allowed for the installation of the necessary infrastructures required by a carrier.

The Acquila

The transformation work began immediately. The underwater part of the hull was modified with the installation of saddle-tanks to minimize the wake and allow for a better flow of the water around the hull, which was widened about 5 meters. The internal compartments were completely reorganized to allow for the installation for the hangar capable of hosting 30 to 40 planes, and the necessary shops and support systems.

The original four Parsons turbines, capable of 21.5 knots, were completely replaced. Instead were installed four turbines originally planned for the light cruisers “Capitani Romani” class made available by the cancellation of 4 of the original 12 vessels. Each turbine was capable of 50,000 HP, but on this installation they were limited to 37,500, also replaced were the propellers which were designed for this larger, but slower ship.

The superstructure consisted in a multi-desk fore-bridge placed amidships on the starboard, followed by a large funnel to which were directed the exhaust from the boilers. The flight deck was continuos, from bow to stern, and obviously integral part of the hull, but was held by special structures. To the side of the deck were several ledges holding both the ship’s armament and some of the equipment.

Armament was mostly designed for antiaircraft defense and included 8 135/45 guns and 12 65/64 on single mounts placed on the ledges to the side of the deck. Also, defense included 132 20/65 machine guns in 22 sextuple mounting distributed to the sides of the deck and in front and back of the island. As on can see, the armament was quite respectable and surely adequate.

The air wing consisted of 51 aircraft. The type selected (it had been decided not to develop a plane specifically for this use due to the long development times) was the fighter Reggiane RE-2001. It was a single engine single-seater, which had entered service in 1941 and was powered by a 1,175 HP Daimler Benz (build under license by Alfa Romeo) and capable of a maximum speed of 540 Km/h. Armament consisted of two 12.7 mm and two 7.7 mm guns. Also, the plane had a centrally mounted hook for the installation of a bomb (for the utilization of the plane as a bomber). The version embarked had a substantially modified undercarriage, strengthen for the deck landing and also was equipped with stopping hook. The installation of the 51 planes was a classic example of Italian ingenuity since the hangars could only host 36 planes (respectively 26 and 10), the remaining planes were literally hang from the ceiling thus bringing the total capacity to 51. There was also in the planning the construction of a version of the Re-2001 with folding wings. With this model, the ship would have been able to deploy 66 aircraft.

Re-2001

Protection, obviously, was quite limited and was essentially limited to the vital parts. There was no protection for the flight deck, there was no protective belt, but only a light protection around the rudder. Also, some of the bulkheads were filled with concrete to increase protection.

It was destine, however, that Italy would conclude the war without an aircraft carrier. In September 1943 the Aquila, now almost completed and for sea trials, was caught by the armistice in Genoa and was captured by the Germans. It was later damaged during an allied aerial bombardment on June 16th, 1944 and later sunk by Italian insidious weapons on April 19th, 1945. The relict was later rescued and scuttle after the war.

Aquila was not to be alone. In 1942 it was decided to transform into an aircraft carrier the Roma’s quasi-sister ship Augustus. This transformation was to be very limited. The Sparviero (this was the designated name) was scheduled to be a support carrier similar to the allied ships: continuos flight deck, no island, later exhaust, and armed with 6 152 mm and 4 102 mm guns placed to the side of the deck. The ship was to have a wing of about 20 planes.

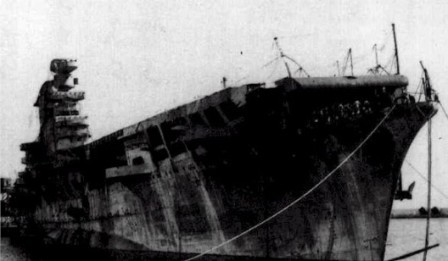

The wreck of the Sparviero in Genoa after the war

The engine was to be the original diesel one, capable of 18 knots. Work began in November 1942, but was stopped by the armistice the following year at an earlier stage. Practically, the ship had been “shaven” down to the main deck, but none of the structure had been build. This transformation, like the one before, went up in smoke in the nebulous times of September 8th. The Italian Navy had to wait until 1985 before it could receive its first carrier, almost forty years later, when the cruiser-carrier (or light carrier) Giuseppe Garibaldi entered service.

Final Considerations

The history of the Italian carriers during WW II cannot be completed without some final considerations. It was said that if the Regia Marina had had an aircraft carrier it would have been able to fight the Royal Navy on a plain level and that certain events (see Matapan), would have taken a different turn.

The Acquila at the end of the war

It is opportune to consider a few things. First of all, the number of this fantasy carriers. Considering their cost of this kind of unit, and the shipbuilding capabilities of the Italian industries, it would not be logical to assume that Italy could have had more that one or two units (at the very best three). France, for instance, had only the Béarn plus two more planned. Similarly, it is plausible to assume that these ships would have not been large carriers of the class of the Saratoga or Akagi, but vessel with lesser characteristics as we so in the projects presented between the wars.

With two carriers in service, means that beside some rare exceptions, only one unit would be available while the other is been refitted, worked on or upgraded. Also, considering that these units would have been the primary target of the British forces, it is safe to assume that at least one would have been sunk. So, what could have these few carriers do? Escort the fleet in its rare excursions in pursuit of enemy vessel? Escort convoy to North Africa, thus securing aerial coverage? Both? Antisubmarine patrol? As one can see these are many assignments which two carriers alone cannot accomplish. If they had been with the fleet, maybe at Matapan the three cruisers and the two destroyers would have not been lost. Maybe, the Italian could have destroyed a few British convoys, but the faith on the Italian ones would have not changed.

If the carrier had escorted the convoys, Rommel would have received a greater quantity of supply, but the ultimate faith of the African campaign would have not changed and the fleet would have been left without the assuring eyes of naval aviation. If submarine hunting had been a priority, then it would have been only a fruitless effort not worth the risk of getting a torpedo up the hull.

Ultimately, we are brought to conclude that these two or three carriers which Mussolini’s Italy could have afforded, would have not reasonably changed the course of the events of WW II. Surely, they would have been useful to the naval operations (no doubts here), and could have avoided horrendous episodes (horrendous for the final result, but not for the bravery demonstrated by the Italian sailors), but what would have really served Italy, perhaps more than carriers, would have been a strong naval aviation organized in bases distributed on the national territory and overseas allowing for good coverage of the Mediterranean and a good coordination with the operations of the fleet. This would have allowed an even better utilization of the carriers, thus giving it its maximum value.

Translated from Italian by Cristiano D’Adamo