| Abastro | | Abastro | Minesweeper | Neptun, Rostok | | | | | |

| Acciaio | AC | Platino | Submarine – Coastal | Odero-Terni-Orlandi (O.T.O.), Muggiano (La Spezia) | 11/21/1940 | 6/22/1941 | 10/30/1941 | Sunk | 7/13/1943 |

| Acquilone | AL | Turbine | Destroyer | Odero-Terni-Orlandi (O.T.O.), Genova-Sestri Ponente | 5/18/1925 | 8/3/1927 | 12/3/1927 | Sunk | 7/27/1940 |

| Adua | AD | Adua | Submarine – Coastal | Cantieri Riuniti dell’Adriatico (C.R.D.A.), Monfalcone | 2/1/1936 | 9/13/1936 | 11/14/1936 | Sunk | 9/30/1941 |

| Airone | AO | Spica tipo Alcione | Torpedo Boat | Ansaldo, Sestri Levante | 10/29/1936 | 1/23/1938 | 5/10/1938 | Sunk | 10/12/1940 |

| Alabarda | | Ariete | Torpedo Boat | Cantieri Riuniti dell’Adriatico (C.R.D.A.), Monfalcone | 3/24/1943 | 5/7/1944 | 11/27/1944 | Captured | 9/9/1943 |

| Alabastro | AB | Platino | Submarine – Coastal | Cantieri Riuniti dell’Adriatico (C.R.D.A.), Monfalcone | 3/14/1941 | 12/18/1941 | 5/9/1942 | Sunk | 9/14/1942 |

| Alagi | AL | Adua | Submarine – Coastal | Cantieri Riuniti dell’Adriatico (C.R.D.A.), Monfalcone | 3/19/1936 | 11/15/1936 | 3/6/1937 | Removed from Service | 9/9/1943 |

| Alberico da Barbiano | | Condottieri tipo Di Giussano | Cruiser – Light | Ansaldo, Sestri Levante | 4/16/1928 | 8/23/1930 | 6/9/1931 | Sunk | 12/13/1941 |

| Alberto da Giussano | | Condottieri tipo Di Giussano | Cruiser – Light | Ansaldo, Sestri Levante | 3/29/1928 | 4/27/1930 | 2/5/1931 | Sunk | 12/31/1941 |

| Alce | C 23 | Gabbiano | Corvette | Odero-Terni-Orlandi (O.T.O.), Livorno | 5/27/1942 | 12/5/1942 | | Captured | 9/9/1943 |

| Alcione | AC | Spica tipo Alcione | Torpedo Boat | Ansaldo, Sestri Levante | 10/29/1936 | 12/23/1937 | 5/10/1938 | Sunk | 12/11/1941 |

| Alderaban | AL | Spica tipo Perseo | Torpedo Boat | Ansaldo, Sestri Levante | 10/2/1935 | 6/14/1936 | 6/12/1936 | Sunk | 10/24/1941 |

| Alessandro Malaspina | MA | Marconi | Submarine – Oceanic | Odero-Terni-Orlandi (O.T.O.), Muggiano (La Spezia) | 3/1/1939 | 2/18/1940 | 6/20/1940 | Sunk | 9/10/1941 |

| Alfredo Oriani | OA | Oriani | Destroyer | Odero-Terni-Orlandi (O.T.O.), Livorno | 10/28/1935 | 7/30/1936 | 7/15/1937 | Transferred | 1/1/1948 |

| Aliseo | AS | Orsa 2a Serie | Torpedo Boat | Navalmeccanica, Castellammare | 9/16/1941 | 9/20/1942 | 2/28/1943 | | |

| Alpino | AP | Soldati 1a Serie | Destroyer | Cantiere Navale Riuniti (C.N.R.) Ancona | 5/2/1937 | 9/8/1938 | 4/20/1939 | Sunk | 4/19/1943 |

| Alpino Bagnolini | BI | Liuzzi | Submarine – Oceanic | Tosi, Taranto | 12/15/1938 | 10/28/1939 | 12/22/1939 | Captured | 3/11/1943 |

| Altair | AT | Spica tipo Perseo | Torpedo Boat | Ansaldo, Sestri Levante | 10/2/1935 | 7/26/1936 | 12/23/1936 | Sunk | 10/20/1941 |

| Alvise Da Mosto | DM | Navigatori | Destroyer | Cantieri Navali del Quarnaro (C.N.Q.), Fiume | 8/22/1928 | 7/1/1929 | 3/15/1931 | Sunk | 12/1/1941 |

| Ambra | PL | Perla | Submarine – Coastal | Cantieri Riuniti dell’Adriatico (C.R.D.A.), Monfalcone | 8/28/1935 | 5/28/1936 | 8/4/1936 | Scuttled | 9/9/1943 |

| Ametista | AA | Sirena | Submarine – Coastal | Odero-Terni-Orlandi (O.T.O.), Muggiano (La Spezia) | 9/16/1931 | 4/26/1933 | 4/1/1934 | Scuttled | 9/12/1943 |

| Ammiraglio Cagni | CA | Ammiragli | Submarine – Oceanic | Cantieri Riuniti dell’Adriatico (C.R.D.A.), Monfalcone | 9/16/1939 | 7/20/1940 | 8/21/1941 | Removed from Service | 9/9/1943 |

| Ammiraglio Caracciolo | CC | Ammiragli | Submarine – Oceanic | Cantieri Riuniti dell’Adriatico (C.R.D.A.), Monfalcone | 10/16/1939 | 10/16/1940 | 9/15/1941 | Sunk | 12/11/1941 |

| Ammiraglio Millo | MG | Ammiragli | Submarine – Oceanic | Cantieri Riuniti dell’Adriatico (C.R.D.A.), Monfalcone | 10/16/1939 | 8/31/1940 | 7/15/1941 | Sunk | 5/13/1943 |

| Ammiraglio Saint Bon | SB | Ammiragli | Submarine – Oceanic | Cantieri Riuniti dell’Adriatico (C.R.D.A.), Monfalcone | 9/16/1939 | 6/6/1940 | 3/12/1941 | Sunk | 1/5/1942 |

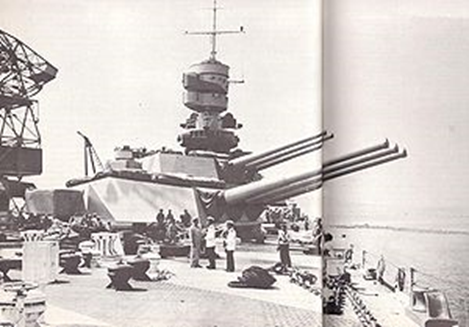

| Andrea Doria | | Duilio | Battleship | Arsenale Navale, La Spezia | 4/1/1937 | 10/26/1940 | 10/26/1940 | Removed from Service | 6/15/1956 |

| Andromeda | AD | Spica tipo Perseo | Torpedo Boat | Ansaldo, Sestri Levante | 10/2/1935 | 6/28/1936 | 12/6/1936 | Sunk | 3/17/1941 |

| Anfitrite | AN | Sirena | Submarine – Coastal | Cantieri Riuniti dell’Adriatico (C.R.D.A.), Monfalcone | 7/11/1931 | 7/5/1933 | 3/22/1934 | Scuttled | 3/6/1941 |

| Angelo Bassini | | La Masa | Destroyer | Odero-Terni-Orlandi (O.T.O.), Genova-Sestri Ponente | | | | | |

| Animoso | AM | Orsa 2a Serie | Torpedo Boat | Ansaldo, Sestri Levante | 4/3/1941 | 4/15/1942 | 8/14/1942 | | |

| Antares | AN | Spica tipo Perseo | Torpedo Boat | Ansaldo, Sestri Levante | 10/2/1935 | 7/19/1936 | 12/23/1936 | Sunk | 5/28/1943 |

| Antilope | C 19 | Gabbiano | Corvette | Odero-Terni-Orlandi (O.T.O.), Livorno | 1/20/1942 | 5/9/1942 | 11/11/1942 | Captured | 9/9/1943 |

| Antonio Biamonti | | Osvetnik | Submarine – Coastal | Loires, Nantes (France) | | 12/1/1928 | 4/1/1941 | Scuttled | 8/9/1943 |

| Antonio Da Noli | DN | Navigatori | Destroyer | Cantieri del Tirreno (C.T.), Genova-Riva Trigoso | 7/25/1927 | 5/21/1929 | 12/29/1929 | Sunk | 7/9/1943 |

| Antonio Mosto | | Rosolino Pilo | Destroyer | Pattison, Napoli | | | | | |

| Antonio Pigafetta | PI | Navigatori | Destroyer | Cantieri Navali del Quarnaro (C.N.Q.), Fiume | 12/29/1927 | 11/10/1929 | 5/1/1931 | Captured | 10/1/1944 |

| Antonio Sciesa | SC | Balilla | Submarine – Oceanic | Odero-Terni-Orlandi (O.T.O.), Muggiano (La Spezia) | 10/20/1925 | 8/18/1928 | 4/12/1929 | Scuttled | 11/6/1942 |

| Antoniotto Usodimare | US | Navigatori | Destroyer | Odero-Terni-Orlandi (O.T.O.), Genova-Sestri Ponente | 6/1/1927 | 5/12/1929 | 11/21/1929 | Sunk | 6/8/1942 |

| Ape | C 25 | Gabbiano | Corvette | Navalmeccanica, Castellammare | 5/6/1942 | 11/22/1942 | 5/15/1943 | | |

| Aquila | | Aquila | Aircraft Carrier | Ansaldo, Sestri Levante | | | | Captured | 9/8/1943 |

| Aradam | AR | Adua | Submarine – Coastal | Cantieri Riuniti dell’Adriatico (C.R.D.A.), Monfalcone | 3/14/1936 | 10/18/1936 | 1/16/1937 | Scuttled | 9/9/1943 |

| Arbe | | Arbe | Minelayer | Kraljevica, Jugoslavia | | | | | |

| Archimede | AH | Brin | Submarine – Oceanic | Tosi, Taranto | 12/23/1937 | 3/5/1939 | 4/18/1939 | Sunk | 4/15/1943 |

| Ardea | C 54 | Gabbiano | Corvette | Ansaldo, Sestri Levante | 3/15/1943 | | | Captured | 9/9/1943 |

| Ardente | AD | Orsa 2a Serie | Torpedo Boat | Ansaldo, Sestri Levante | 4/7/1941 | 5/27/1942 | 9/30/1942 | Wrecked | 1/12/1943 |

| Ardimentoso | AT | Orsa 2a Serie | Torpedo Boat | Ansaldo, Sestri Levante | 4/7/1941 | 6/28/1942 | 12/14/1942 | | |

| Ardito | AR | Orsa 2a Serie | Torpedo Boat | Ansaldo, Sestri Levante | 4/3/1941 | 3/14/1942 | 6/30/1942 | Captured | 9/16/1943 |

| Aretusa | AU | Spica tipo Alcione | Torpedo Boat | Ansaldo, Sestri Levante | 10/26/1936 | 2/6/1938 | 7/1/1938 | | |

| Argento | AG | Platino | Submarine – Coastal | Tosi, Taranto | 4/30/1941 | 2/22/1942 | 5/16/1942 | Scuttled | 8/3/1943 |

| Argo | AO | Argo | Submarine – Coastal | Cantieri Riuniti dell’Adriatico (C.R.D.A.), Monfalcone | 12/9/1935 | 11/24/1936 | 8/31/1937 | Scuttled | 9/10/1943 |

| Argonauta | AU | Argonauta | Submarine – Coastal | Cantieri Riuniti dell’Adriatico (C.R.D.A.), Monfalcone | 11/9/1929 | 1/19/1931 | 1/14/1932 | Sunk | 6/29/1940 |

| Ariel | AE | Spica tipo Alcione | Torpedo Boat | Ansaldo, Sestri Levante | 10/29/1936 | 3/14/1938 | 7/1/1938 | Sunk | 10/12/1940 |

| Ariete | | Ariete | Torpedo Boat | Ansaldo, Sestri Levante | 7/15/1942 | 3/6/1943 | 8/5/1943 | | |

| Armando Diaz | | Condottieri tipo Cadorna | Cruiser – Light | Odero-Terni-Orlandi (O.T.O.), Muggiano (La Spezia) | 7/28/1930 | 7/10/1932 | 4/29/1933 | Sunk | 2/25/1941 |

| Artemide | C 39 | Gabbiano | Corvette | Cantieri Riuniti dell’Adriatico (C.R.D.A.), Monfalcone | 3/9/1942 | 8/10/1942 | 10/10/1942 | Captured | 9/9/1943 |

| Artigliere | AR | Soldati 1a Serie | Destroyer | Odero-Terni-Orlandi (O.T.O.), Livorno | 2/15/1937 | 12/12/1937 | 11/14/1938 | Sunk | 10/12/1940 |

| Arturo | | Ariete | Torpedo Boat | Ansaldo, Sestri Levante | 7/15/1942 | 3/27/1943 | 10/4/1943 | Captured | 9/9/1943 |

| Ascari | AI | Soldati 1a Serie | Destroyer | Odero-Terni-Orlandi (O.T.O.), Livorno | 12/11/1937 | 7/31/1938 | 5/6/1939 | Sunk | 3/24/1943 |

| Ascianghi | AS | Adua | Submarine – Coastal | Odero-Terni-Orlandi (O.T.O.), Muggiano (La Spezia) | 1/20/1937 | 7/5/1937 | 3/25/1938 | Sunk | 7/23/1943 |

| Asteria | AE | Platino | Submarine – Coastal | Cantieri Riuniti dell’Adriatico (C.R.D.A.), Monfalcone | 10/16/1940 | 5/25/1941 | 11/8/1941 | Sunk | 2/17/1943 |

| Atropo | AT | Foca | Submarine – Medium Range | Tosi, Taranto | 7/10/1937 | 11/20/1938 | 2/14/1939 | Stricken | 9/9/1943 |

| Attilio Regolo | | Capitani Romani | Cruiser – Light | Odero-Terni-Orlandi (O.T.O.), Livorno | 9/28/1939 | 8/28/1940 | 5/14/1942 | Removed from Service | 7/26/1948 |

| Augusto Riboty | RI | Maestrale | Destroyer | Ansaldo, Sestri Levante | 2/27/1915 | 9/24/1916 | 5/5/1917 | Transferred | |

| Auriga | | Ariete | Torpedo Boat | Ansaldo, Sestri Levante | 7/15/1942 | 4/15/1943 | 12/28/1943 | Captured | 9/9/1943 |

| Aviere | AV | Soldati 1a Serie | Destroyer | Odero-Terni-Orlandi (O.T.O.), Livorno | 1/16/1937 | 9/19/1937 | 8/31/1938 | Sunk | 12/17/1942 |

| Avorio | AV | Platino | Submarine – Coastal | Cantieri Riuniti dell’Adriatico (C.R.D.A.), Monfalcone | 11/9/1940 | 9/6/1941 | 3/25/1942 | Sunk | 2/9/1943 |

| Axum | AX | Adua | Submarine – Coastal | Cantieri Riuniti dell’Adriatico (C.R.D.A.), Monfalcone | 3/8/1936 | 9/27/1936 | 12/2/1936 | Scuttled | 12/28/1943 |

| Azio | | Ostia | Minelayer | Cantiere Navale Riuniti (C.N.R.) Ancona | | | | | |

| Azio | | Ostia | Mine Layer | Cantiere Navale Riuniti (C.N.R.) Ancona | 1/1/1925 | 1/1/1927 | | | |

| Baiamonti | BM | Bajamonti | Submarine – Coastal | Loires, Nantes (France) | 1/1/1927 | 12/1/1928 | 12/2/1928 | Scuttled | 9/9/1943 |

| Baionetta | C 34 | Gabbiano | Corvette | Breda, Venezia | 2/24/1942 | 10/5/1942 | 5/15/1943 | | |

| Baleno | BO | Dardo 2a Serie | Destroyer | Cantieri Navali del Quarnaro (C.N.Q.), Fiume | 10/1/1929 | 3/22/1931 | 6/15/1932 | Sunk | 4/17/1941 |

| Balestra | | Ariete | Torpedo Boat | Cantieri Navali del Quarnaro (C.N.Q.), Fiume | 9/5/1943 | | | | |

| Balilla | BL | Balilla | Submarine – Oceanic | Odero-Terni-Orlandi (O.T.O.), Muggiano (La Spezia) | 1/12/1925 | 2/20/1927 | 7/20/1928 | Stricken | 4/28/1941 |

| Barbarigo | BO | Marcello | Submarine – Oceanic | Cantieri Riuniti dell’Adriatico (C.R.D.A.), Monfalcone | 2/6/1937 | 6/12/1938 | 9/19/1938 | Sunk | 6/16/1943 |

| Bari | | Bari | Obsolete Ship | Schichau, Danzig (Germany) | 12/31/1912 | 4/4/1914 | 12/14/1914 | Sunk | 6/28/1943 |

| Battolomeo Colleoni | | Condottieri tipo Di Giussano | Cruiser – Light | Ansaldo, Sestri Levante | 6/21/1928 | 12/21/1930 | 2/10/1932 | Sunk | 7/19/1940 |

| Bausan | BN | Pisani | Submarine – Medium Range | Cantieri Riuniti dell’Adriatico (C.R.D.A.), Monfalcone | 1/20/1926 | 3/24/1928 | 9/15/1929 | Removed from Service | 11/8/1941 |

| Beilul | BU | Adua | Submarine – Coastal | Odero-Terni-Orlandi (O.T.O.), Muggiano (La Spezia) | 7/2/1937 | 5/22/1938 | 9/14/1938 | Sunk | 9/9/1943 |

| Berenice | C 66 | Gabbiano | Corvette | Cantieri Riuniti dell’Adriatico (C.R.D.A.), Monfalcone | 10/1/1942 | 4/21/1943 | 8/1/1943 | | |

| Berillo | BE | Perla | Submarine – Coastal | Cantieri Riuniti dell’Adriatico (C.R.D.A.), Monfalcone | 9/14/1935 | 6/14/1936 | 8/5/1936 | Scuttled | 10/2/1940 |

| Bersagliere | BG | Soldati 1a Serie | Destroyer | Cantiere Navale Riuniti (C.N.R.) Ancona | 4/21/1937 | 7/3/1938 | 4/1/1939 | Sunk | 1/7/1943 |

| Bettino Ricasoli | RC | Sella | Destroyer | Pattison, Napoli | 1/11/1923 | 1/29/1926 | 12/11/2026 | Transferred | 3/1/1940 |

| Bolzano | | Bolzano | Cruiser – Heavy | Ansaldo, Sestri Levante | 6/11/1930 | 8/31/1932 | 8/19/1933 | Sunk | 6/22/1944 |

| Bombarda | C 38 | Gabbiano | Corvette | Breda, Venezia | 8/31/1942 | | | Captured | 9/11/1943 |

| Bombardiere | BR | Soldati 2a Serie | Destroyer | Cantiere Navale Riuniti (C.N.R.) Ancona | 10/7/1940 | 3/23/1942 | 7/15/1942 | Sunk | 1/17/1943 |

| Borea | BR | Turbine | Destroyer | Ansaldo, Sestri Levante | 4/29/1925 | 1/28/1927 | 11/24/1927 | Sunk | 7/17/1940 |

| Brin | BR | Brin | Submarine – Oceanic | Tosi, Taranto | 12/3/1936 | 4/3/1938 | 6/30/1938 | Stricken | 9/9/1943 |

| Bronzo | BZ | Platino | Submarine – Coastal | Tosi, Taranto | 12/2/1940 | 9/28/1941 | 1/2/1942 | Captured | 7/12/1943 |

| Buccari | | Fasana | Minelayer | Navalmeccanica, Castellammare | | | | | |

| CA 1 | | CA I | Submarine – Midget | Caproni Taliedo | | | 4/15/1938 | Scuttled | 9/9/1943 |

| CA 2 | | CA I | Submarine – Midget | Caproni Taliedo | | | | Captured | 9/9/1943 |

| CA 3 | | CA I | Submarine – Midget | Caproni Taliedo | | | | Removed from Service | 9/9/1943 |

| CA 4 | | CA I | Submarine – Midget | Caproni Taliedo | | | | Removed from Service | 9/9/1943 |

| Caio Duilio | | Duilio | Battleship | Navalmeccanica, Castellammare | 4/8/1937 | 7/15/1940 | 7/15/1940 | Removed from Service | 11/1/1956 |

| Calabrone | C 30 | Gabbiano | Corvette | Navalmeccanica, Castellammare | 10/1/1942 | 6/27/1943 | | Captured | 9/9/1943 |

| Calipso | CI | Spica tipo Alcione | Torpedo Boat | Ansaldo, Sestri Levante | 9/29/1937 | 6/12/1938 | 11/16/1938 | Sunk | 12/5/1940 |

| Calliope | CP | Spica tipo Alcione | Torpedo Boat | Ansaldo, Sestri Levante | 5/26/1937 | 4/15/1938 | 10/28/1938 | | |

| Camicia Nera | CN | Soldati 1a Serie | Destroyer | Odero-Terni-Orlandi (O.T.O.), Livorno | 1/21/1937 | 8/8/1937 | 6/30/1938 | Transferred | 2/21/1949 |

| Camoscio | C 21 | Gabbiano | Corvette | Odero-Terni-Orlandi (O.T.O.), Livorno | 1/25/1942 | 5/9/1942 | 4/18/1943 | | |

| Canopo | CA | Spica tipo Climene | Torpedo Boat | Cantieri del Tirreno (C.T.), Genova-Riva Trigoso | 12/10/1935 | 10/1/1936 | 3/31/1937 | Sunk | 5/3/1941 |

| Capitano Tarantini | TA | Liuzzi | Submarine – Oceanic | Tosi, Taranto | 4/5/1939 | 1/7/1940 | 3/16/1930 | Sunk | 12/15/1940 |

| Capriolo | C 22 | Gabbiano | Corvette | Odero-Terni-Orlandi (O.T.O.), Livorno | 6/3/1942 | 12/5/1942 | | Captured | 9/9/1943 |

| Carabina | C 37 | Gabbiano | Corvette | Breda, Venezia | 9/28/1942 | 8/31/1943 | | Captured | 9/11/1943 |

| Carabiniere | CB | Soldati 1a Serie | Destroyer | Cantieri del Tirreno (C.T.), Genova-Riva Trigoso | 2/1/1937 | 7/23/1937 | 12/20/1938 | Removed from Service | 1/18/1965 |

| Carlo Mirabello | MI | Maestrale | Destroyer | Ansaldo, Sestri Levante | 11/21/1914 | 12/21/1915 | 8/24/1916 | Sunk | 5/21/1941 |

| Carrista | CR | Soldati 2a Serie | Destroyer | Odero-Terni-Orlandi (O.T.O.), Livorno | 9/11/1941 | | | Removed from Service | |

| Cassiopea | CS | Spica tipo Climene | Torpedo Boat | Cantieri del Tirreno (C.T.), Genova-Riva Trigoso | 12/10/1935 | 11/22/1936 | 4/26/1937 | | |

| Castelfitardo | | Curtatone | Destroyer | Orlando, Livorno | 1/1/1920 | 1/1/1922 | 1/1/1923 | Captured | 1/1/1943 |

| Castore | CT | Spica tipo Climene | Torpedo Boat | Cantiere Navale Riuniti (C.N.R.) Ancona | 1/25/1936 | 9/27/1936 | 1/16/1937 | Sunk | 6/2/1943 |

| Catalafimi | | Curtatone | Destroyer | Orlando, Livorno | 1/1/1920 | 1/1/1922 | 1/1/1923 | Captured | 1/1/1943 |

| Cavalletta | C 31 | Gabbiano | Corvette | Navalmeccanica, Castellammare | 3/12/1942 | | | | |

| CB 1 | | CB | Submarine – Coastal | Caproni Taliedo | | | 1/27/1941 | Transferred | 9/9/1943 |

| CB 10 | | CB | Submarine – Coastal | Caproni Taliedo | | | 8/1/1943 | Removed from Service | |

| CB 11 | | CB | Submarine – Coastal | Caproni Taliedo | | | 8/24/1943 | Scuttled | 9/11/1943 |

| CB 12 | | CB | Submarine – Coastal | Caproni Taliedo | | | 8/24/1943 | Scuttled | 9/11/1943 |

| CB 13 | | CB | Submarine – Coastal | Caproni Taliedo | | | | Sunk | 3/23/1945 |

| CB 14 | | CB | Submarine – Coastal | Caproni Taliedo | | | | Sunk | |

| CB 15 | | CB | Submarine – Coastal | Caproni Taliedo | | | | Sunk | |

| CB 16 | | CB | Submarine – Coastal | Caproni Taliedo | | | | Surrendered | |

| CB 17 | | CB | Submarine – Coastal | Caproni Taliedo | | | | Sunk | 4/3/1945 |

| CB 18 | | CB | Submarine – Coastal | Caproni Taliedo | | | | Sunk | 3/31/1945 |

| CB 19 | | CB | Submarine – Coastal | Caproni Taliedo | | | | Captured | |

| CB 2 | | CB | Submarine – Coastal | Caproni Taliedo | | | 1/27/1941 | Transferred | 9/9/1943 |

| CB 20 | | CB | Submarine – Coastal | Caproni Taliedo | | | | Captured | |

| CB 21 | | CB | Submarine – Coastal | Caproni Taliedo | | | | Sunk | 4/29/1945 |

| CB 22 | | CB | Submarine – Coastal | Caproni Taliedo | | | | Captured | |

| CB 3 | | CB | Submarine – Coastal | Caproni Taliedo | | | 5/10/1941 | Transferred | 9/9/1943 |

| CB 4 | | CB | Submarine – Coastal | Caproni Taliedo | | | 5/10/1941 | Transferred | 9/9/1943 |

| CB 5 | | CB | Submarine – Coastal | Caproni Taliedo | | | 5/10/1941 | Sunk | 6/13/1942 |

| CB 6 | | CB | Submarine – Coastal | Caproni Taliedo | | | 5/10/1941 | Transferred | 9/9/1943 |

| CB 7 | | CB | Submarine – Coastal | Caproni Taliedo | | | 8/1/1943 | Removed from Service | |

| CB 8 | | CB | Submarine – Coastal | Caproni Taliedo | | | 8/1/1943 | Removed from Service | |

| CB 9 | | CB | Submarine – Coastal | Caproni Taliedo | | | 8/1/1943 | Removed from Service | |

| Centauro | CO | Spica tipo Climene | Torpedo Boat | Cantiere Navale Riuniti (C.N.R.) Ancona | 5/30/1934 | 2/19/1936 | 6/16/1936 | Sunk | 11/4/1942 |

| Cernia | | Tritone | Submarine – Coastal | Tosi, Taranto | 7/12/1943 | | | Stricken | |

| Cervo | C 56 | Gabbiano | Corvette | Odero-Terni-Orlandi (O.T.O.), Livorno | 2/25/1943 | | | | |

| Cesare Battisti | BT | Sauro | Destroyer | Odero-Terni-Orlandi (O.T.O.), Genova-Sestri Ponente | 2/9/1924 | 12/11/1926 | 4/13/1927 | Scuttled | 4/3/1941 |

| Chimera | C 48 | Gabbiano | Corvette | Cantieri Riuniti dell’Adriatico (C.R.D.A.), Monfalcone | 6/27/1942 | 1/30/1943 | 5/26/1943 | | |

| Cicala | C 29 | Gabbiano | Corvette | Navalmeccanica, Castellammare | 9/30/1942 | 6/27/1943 | | Captured | 9/9/1943 |

| Ciclone | CI | Orsa 2a Serie | Torpedo Boat | Cantieri Riuniti dell’Adriatico (C.R.D.A.), Monfalcone | 5/9/1941 | 3/1/1942 | 5/21/1942 | Sunk | 3/8/1943 |

| Cicogna | C 15 | Gabbiano | Corvette | Ansaldo, Sestri Levante | 6/15/1942 | 10/12/1942 | 1/11/1943 | Wrecked | 7/24/1943 |

| Cigno | CG | Spica tipo Climene | Torpedo Boat | Cantiere Navale Riuniti (C.N.R.) Ancona | 3/11/1936 | 11/24/1936 | 3/15/1937 | Sunk | 4/16/1943 |

| Circe | CC | Spica tipo Alcione | Torpedo Boat | Ansaldo, Sestri Levante | 9/29/1937 | 6/29/1938 | 10/4/1938 | Sunk | 11/27/1942 |

| Ciro Menotti | ME | Bandiera | Submarine – Medium Range | Odero-Terni-Orlandi (O.T.O.), Muggiano (La Spezia) | 5/12/1928 | 7/29/1929 | 7/29/1930 | Stricken | 9/9/1943 |

| Clava | C 63 | Gabbiano | Corvette | Breda, Venezia | 10/20/1943 | | | | |

| Climene | CE | Spica tipo Climene | Torpedo Boat | Cantiere Navale Riuniti (C.N.R.) Ancona | 7/25/1934 | 1/7/1936 | 4/24/1936 | Sunk | 4/28/1943 |

| Clio | CL | Spica tipo Alcione | Torpedo Boat | Ansaldo, Sestri Levante | 10/29/1936 | 4/3/1938 | 10/2/1938 | | |

| Cobalto | CB | Platino | Submarine – Coastal | Odero-Terni-Orlandi (O.T.O.), Muggiano (La Spezia) | 11/26/1940 | 8/20/1941 | 3/18/1942 | Sunk | 8/12/1942 |

| Cocciniglia | C 61 | Gabbiano | Corvette | Navalmeccanica, Castellammare | | | | | |

| Cofienza | | Palestro | Destroyer | Orlando, Livorno | | | | | |

| Colubrina | C 35 | Gabbiano | Corvette | Breda, Venezia | 3/14/1942 | 12/7/1942 | | Captured | 9/11/1943 |

| Comandante Cappellini | CL | Marcello | Submarine – Oceanic | Odero-Terni-Orlandi (O.T.O.), Muggiano (La Spezia) | 4/25/1938 | 5/14/1939 | 9/23/1939 | Captured | 9/8/1943 |

| Comandante Faa Di Bruno | FB | Marcello | Submarine – Oceanic | Odero-Terni-Orlandi (O.T.O.), Muggiano (La Spezia) | 4/28/1938 | 6/18/1939 | 10/23/1939 | Sunk | 10/31/1940 |

| Console Generale Liuzzi | LZ | Liuzzi | Submarine – Oceanic | Tosi, Taranto | 10/1/1938 | 9/17/1939 | 11/21/1939 | Sunk | 6/27/1940 |

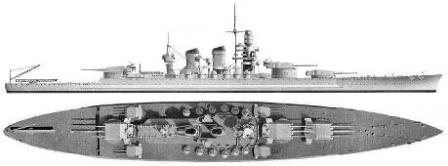

| Conte di Cavour | | Cavour | Battleship | Cantieri Riuniti dell’Adriatico (C.R.D.A.), Monfalcone | 10/1/1933 | 6/1/1937 | 10/1/1937 | Removed from Service | 12/15/1948 |

| Corallo | CO | Perla | Submarine – Coastal | Cantieri Riuniti dell’Adriatico (C.R.D.A.), Monfalcone | 10/1/1935 | 8/2/1936 | 9/26/1936 | Sunk | 12/13/1942 |

| Corazziere | CZ (CR) | Soldati 1a Serie | Destroyer | Odero-Terni-Orlandi (O.T.O.), Livorno | 10/7/1937 | 5/22/1938 | 3/4/1939 | Scuttled | 9/9/1943 |

| Cormorano | C 13 | Gabbiano | Corvette | Societa Anonima Cantieri Cerusa, Genova-Voltri | 1/14/1942 | 9/20/1942 | 3/6/1943 | | |

| Corridoni | CR | Bragadin | Submarine – Minelaying | Tosi, Taranto | 7/4/1927 | 3/30/1930 | 11/17/1931 | Stricken | 9/8/1943 |

| Corsaro | CA | Soldati 2a Serie | Destroyer | Odero-Terni-Orlandi (O.T.O.), Livorno | 1/23/1941 | 11/16/1941 | 5/16/1942 | Sunk | 1/9/1943 |

| Crisalide | C 58 | Gabbiano | Corvette | Navalmeccanica, Castellammare | | | | | |

| Curtatore | | Curtatone | Destroyer | Orlando, Livorno | 1/1/1920 | 1/1/1922 | 1/1/1923 | Sunk | 1/1/1941 |

| D1 | | D1 | Minesweeper | Cantiere Navale Riuniti (C.N.R.) Ancona | | | | | |

| D10 | | D10 | Minesweeper | Cantieri Navali del Quarnaro (C.N.Q.), Fiume | | | | | |

| Da Procida | DP | Mameli | Submarine – Medium Range | Tosi, Taranto | 9/21/1925 | 4/1/1928 | 1/20/1929 | Stricken | 9/8/1943 |

| Daga | | Ariete | Torpedo Boat | Cantieri Riuniti dell’Adriatico (C.R.D.A.), Monfalcone | 1/9/1943 | 7/15/1943 | 3/27/1944 | Captured | 9/9/1943 |

| Dagabur | DA | Adua | Submarine – Coastal | Tosi, Taranto | 4/16/1936 | 9/22/1936 | 4/9/1937 | Sunk | 8/12/1942 |

| Daino | C 55 | Gabbiano | Corvette | Odero-Terni-Orlandi (O.T.O.), Livorno | 3/1/1943 | | | | |

| Danaide | C 44 | Gabbiano | Corvette | Cantieri Riuniti dell’Adriatico (C.R.D.A.), Monfalcone | 5/9/1942 | 10/21/1942 | 2/27/1943 | | |

| Dandolo | DO | Marcello | Submarine – Oceanic | Cantieri Riuniti dell’Adriatico (C.R.D.A.), Monfalcone | 6/14/1937 | 9/20/1937 | 3/25/1938 | Stricken | 9/8/1943 |

| Daniele Manin | MA | Sauro | Destroyer | Cantieri Navali del Quarnaro (C.N.Q.), Fiume | 10/9/1924 | 1/15/1925 | 5/1/1927 | Sunk | 4/3/1941 |

| Dardanelli | | Ostia | Mine Layer | Cantieri Riuniti dell’Adriatico (C.R.D.A.), Monfalcone | 1/1/1925 | 1/1/2925 | | | |

| Dardanelli | | Ostia | Minelayer | Stabilimento Tecnico Triestino, Trieste | | | | | |

| Dardo | DA | Dardo 1a Serie | Destroyer | Odero-Terni-Orlandi (O.T.O.), Genova-Sestri Ponente | 1/23/1929 | 7/6/1930 | 1/25/1932 | Captured | 9/9/1943 |

| Delfino | DL | Squalo | Submarine – Medium Range | Cantieri Riuniti dell’Adriatico (C.R.D.A.), Monfalcone | 10/27/1928 | 4/27/1930 | 6/19/1930 | Sunk | 3/23/1943 |

| Dentice | | Tritone | Submarine – Coastal | Tosi, Taranto | 7/23/1943 | | | Stricken | |

| Des Geneys | DN | Pisani | Submarine – Medium Range | Cantieri Riuniti dell’Adriatico (C.R.D.A.), Monfalcone | 2/1/1926 | 6/14/1928 | 10/31/1929 | Removed from Service | 5/28/1943 |

| Dessiè | DE | Adua | Submarine – Coastal | Tosi, Taranto | 4/20/1936 | 11/22/1936 | 4/14/1937 | Sunk | 11/28/1942 |

| Diamante | DI | Sirena | Submarine – Coastal | Tosi, Taranto | 5/11/1931 | 5/21/1933 | 6/18/1933 | Sunk | 6/20/1940 |

| Diana | | Diana | Destroyer | Cantieri Navali del Quarnaro (C.N.Q.), Fiume | 5/31/1939 | 5/20/1940 | 11/12/1940 | Sunk | 6/29/1942 |

| Diaspro | DS | Perla | Submarine – Coastal | Cantieri Riuniti dell’Adriatico (C.R.D.A.), Monfalcone | 9/21/1935 | 7/5/1936 | 8/28/1936 | Stricken | 9/8/1943 |

| Dragone | | Ariete | Torpedo Boat | Ansaldo, Sestri Levante | 7/15/1942 | 8/14/1943 | 4/3/1944 | Captured | 9/9/1943 |

| Driade | C 43 | Gabbiano | Corvette | Cantieri Riuniti dell’Adriatico (C.R.D.A.), Monfalcone | 5/9/1942 | 10/7/1942 | 1/14/1943 | | |

| Durazzo | | Fasana | Minelayer | Navalmeccanica, Castellammare | | | | | |

| Durbo | DU | Adua | Submarine – Coastal | Odero-Terni-Orlandi (O.T.O.), Muggiano (La Spezia) | 3/8/1937 | 3/6/1938 | 7/1/1938 | Scuttled | 10/18/1940 |

| Egeria | C 67 | Gabbiano | Corvette | Cantieri Riuniti dell’Adriatico (C.R.D.A.), Monfalcone | 2/15/1943 | 7/3/1943 | | Captured | 9/9/1943 |

| Emanuele Filiberto Duca d’Aosta | | Condottieri tipo Duca di Aosta | Cruiser – Light | Odero-Terni-Orlandi (O.T.O.), Livorno | 10/29/1932 | 4/22/1934 | 3/17/1935 | Removed from Service | 2/12/1949 |

| Emanuele Pessagno | PS | Navigatori | Destroyer | Cantiere Navale Riuniti (C.N.R.) Ancona | 10/9/1927 | 8/12/1929 | 3/10/1930 | Sunk | 5/29/1942 |

| Emo | EO | Marcello | Submarine – Oceanic | Cantieri Riuniti dell’Adriatico (C.R.D.A.), Monfalcone | 2/16/1937 | 6/29/1938 | 10/14/1938 | Sunk | 11/10/1942 |

| Enrico Cosenz | | La Masa | Destroyer | Odero-Terni-Orlandi (O.T.O.), Genova-Sestri Ponente | | | | | |

| Enrico Tazzoli | TZ | Calvi | Submarine – Oceanic | Odero-Terni-Orlandi (O.T.O.), Muggiano (La Spezia) | 9/16/1932 | 10/13/1935 | 4/18/1936 | Sunk | 5/18/1943 |

| Eridano | | Ariete | Torpedo Boat | Ansaldo, Sestri Levante | 7/15/1942 | 7/12/1943 | 3/4/1944 | Captured | 9/9/1943 |

| Eritrea | | Eritrea | Corvette | Navalmeccanica, Castellammare | 7/25/1935 | 9/20/1936 | 2/10/1937 | | |

| Ermanno Carlotto | | Carlotto | River Gunboat | Shangai Dode Engineering | 1/1/1920 | 1/1/1921 | 1/1/1921 | Captured | 8/9/1943 |

| Ernestro Giovannini | | Andrea Bafine | Escort Gunboat | Pattison, Napoli | 1/1/1920 | 1/1/1922 | 1/1/1922 | Stricken | |

| Espero | ES | Turbine | Destroyer | Ansaldo, Sestri Levante | 4/29/1925 | 8/31/1927 | | Sunk | 6/28/1940 |

| Etna | | Etna | Cruiser – Light | Cantieri Riuniti dell’Adriatico (C.R.D.A.), Monfalcone | 9/23/1939 | 5/28/1942 | | | |

| Ettore Fieramosca | FM | Fieramosca | Submarine – Oceanic | Tosi, Taranto | 7/17/1926 | 6/14/1929 | 12/5/1931 | Stricken | 3/1/1943 |

| Eugenio di Savoia | | Condottieri tipo Duca di Aosta | Cruiser – Light | Ansaldo, Sestri Levante | 7/6/1933 | 3/16/1935 | 1/16/1936 | Removed from Service | 6/26/1951 |

| Euridice | C 70 | Gabbiano | Corvette | Cantieri Riuniti dell’Adriatico (C.R.D.A.), Monfalcone | 7/1/1943 | | | | |

| Euro | ER | Turbine | Destroyer | Cantieri del Tirreno (C.T.), Genova-Riva Trigoso | 1/24/1925 | 7/7/1927 | 12/22/1927 | Sunk | 10/1/1943 |

| Euterpe | C 41 | Gabbiano | Corvette | Cantieri Riuniti dell’Adriatico (C.R.D.A.), Monfalcone | 4/2/1942 | 10/22/1942 | 1/20/1943 | Scuttled | 9/9/1943 |

| Farfalla | C 59 | Gabbiano | Corvette | Navalmeccanica, Castellammare | | | | | |

| Fasana | | Fasana | Minelayer | Navalmeccanica, Castellammare | | | | | |

| Fenice | C 50 | Gabbiano | Corvette | Cantieri Riuniti dell’Adriatico (C.R.D.A.), Monfalcone | 6/27/1942 | 3/1/1943 | 6/15/1943 | | |

| Ferraris | FE | Galilei | Submarine – Medium Range | Tosi, Taranto | 10/15/1931 | 8/11/1934 | 1/31/1935 | Scuttled | 10/25/1941 |

| Fionda | | Ariete | Torpedo Boat | Cantieri Navali del Quarnaro (C.N.Q.), Fiume | 8/26/1942 | | | | |

| Fisalia | FS | Argonauta | Submarine – Coastal | Cantieri Riuniti dell’Adriatico (C.R.D.A.), Monfalcone | 11/20/1929 | 5/2/1931 | 6/4/1932 | Sunk | 9/28/1941 |

| Fiume | | Zara | Cruiser – Heavy | Stabilimento Tecnico Triestino, Trieste | 4/29/1929 | 4/27/1930 | 11/23/1931 | Sunk | 3/28/1941 |

| Flora | C 46 | Gabbiano | Corvette | Cantieri Riuniti dell’Adriatico (C.R.D.A.), Monfalcone | 5/16/1942 | 12/1/1942 | 4/26/1943 | | |

| Flutto | FL | Tritone | Submarine – Coastal | Cantieri Riuniti dell’Adriatico (C.R.D.A.), Monfalcone | 12/1/1941 | 9/19/1942 | 3/20/1943 | Sunk | 7/11/1943 |

| Foca | FO | Foca | Submarine – Medium Range | Tosi, Taranto | 1/15/1936 | 6/27/1937 | 11/6/1937 | Sunk | 10/15/1940 |

| Folaga | C 16 | Gabbiano | Corvette | Ansaldo, Sestri Levante | 6/15/1942 | 11/14/1942 | 2/16/1943 | | |

| Folgore | FG | Dardo 2a Serie | Destroyer | Partenopei, Napoli | 1/30/1930 | 4/26/1931 | 7/1/1932 | Sunk | 12/2/1942 |

| Fortunale | FT | Orsa 2a Serie | Torpedo Boat | Cantieri Riuniti dell’Adriatico (C.R.D.A.), Monfalcone | 5/9/1941 | 4/18/1942 | 8/16/1942 | | |

| FR 11 (ex jean de Vienne) | | FR11 | Cruiser – Light | Arsenal de la Marine, Lorient | | | | | |

| FR 111 | | FR 111 | Submarine – Medium Range | Arsenal de Brest (France) | 1/1/1924 | 3/16/1926 | 1/20/1943 | Sunk | 2/28/1943 |

| FR 12 (ex La Galissoniere) | | FR12 | Cruiser – Light | Arsenal de la Marine, Lorient | | | | | |

| Francesco Crispi | CP (CR) | Sella | Destroyer | Pattison, Napoli | 2/21/1923 | 9/12/1925 | 4/29/1927 | Captured | |

| Francesco Nullo | NL | Sauro | Destroyer | Cantieri Navali del Quarnaro (C.N.Q.), Fiume | 10/9/1924 | 11/14/1925 | 4/15/1927 | Sunk | 10/21/1940 |

| Francesco Rismondo ex Osvetnik | | Lürssen “S 2” | Motor Torpedo Boat | Lurssen, Vegesak | | | | | |

| Francesco Stocco | | Sirtori | Destroyer | Odero-Terni-Orlandi (O.T.O.), Genova-Sestri Ponente | | | | | |

| Fratelli Bandiera | BA | Bandiera | Submarine – Medium Range | Cantieri Riuniti dell’Adriatico (C.R.D.A.), Monfalcone | 2/11/1928 | 7/7/1929 | 6/2/1930 | Stricken | 9/9/1943 |

| Fratelli Cairoli | | Rosolino Pilo | Destroyer | Odero-Terni-Orlandi (O.T.O.), Genova-Sestri Ponente | | | | | |

| Freccia | FR | Dardo 1a Serie | Destroyer | Cantieri del Tirreno (C.T.), Genova-Riva Trigoso | 2/20/1929 | 8/3/1930 | 10/21/1931 | Sunk | 8/8/1943 |

| Fuciliere | FC | Soldati 1a Serie | Destroyer | Cantiere Navale Riuniti (C.N.R.) Ancona | 5/2/1937 | 7/31/1938 | 2/10/1939 | Transferred | 1/17/1950 |

| Fulmine | FL | Dardo 2a Serie | Destroyer | Cantieri Navali del Quarnaro (C.N.Q.), Fiume | 10/1/1929 | 8/2/1931 | 7/14/1932 | Sunk | 11/9/1941 |

| Gabbiano | C 11 | Gabbiano | Corvette | Societa Anonima Cantieri Cerusa, Genova-Voltri | 1/14/1942 | 6/23/1942 | 10/3/1942 | | |

| Galatea | GT | Sirena | Submarine – Coastal | Cantieri Riuniti dell’Adriatico (C.R.D.A.), Monfalcone | 7/18/1931 | 5/5/1933 | 6/25/1934 | Removed from Service | 9/9/1943 |

| Galilei | GL | Galilei | Submarine – Medium Range | Tosi, Taranto | 10/15/1931 | 3/19/1934 | 10/16/1934 | Captured | 6/19/1940 |

| Galvani | GA | Brin | Submarine – Oceanic | Tosi, Taranto | 12/3/1936 | 5/22/1938 | 7/29/1938 | Sunk | 6/24/1940 |

| Gazzella | C 20 | Gabbiano | Corvette | Odero-Terni-Orlandi (O.T.O.), Livorno | 1/22/1942 | 5/9/1942 | 2/6/1943 | Sunk | 8/5/1943 |

| Gemma | GE | Perla | Submarine – Coastal | Cantieri Riuniti dell’Adriatico (C.R.D.A.), Monfalcone | 9/7/1935 | 5/21/1936 | 7/8/1936 | Sunk | 10/8/1940 |

| Generale Achille Papa | | Cantone | Destroyer | Odero-Terni-Orlandi (O.T.O.), Genova-Sestri Ponente | | | | | |

| Generale Antonio Cantone | | Cantone | Destroyer | Odero-Terni-Orlandi (O.T.O.), Genova-Sestri Ponente | | | | | |

| Generale Antonio Cascino | | Cantone | Destroyer | Odero-Terni-Orlandi (O.T.O.), Genova-Sestri Ponente | | | | | |

| Generale Antonio Chinotto | | Cantone | Destroyer | Odero-Terni-Orlandi (O.T.O.), Genova-Sestri Ponente | | | | | |

| Generale Carlo Montanari | | Cantone | Destroyer | Odero-Terni-Orlandi (O.T.O.), Genova-Sestri Ponente | | | | | |

| Generale Marcello Prestinari | | Cantone | Destroyer | Odero-Terni-Orlandi (O.T.O.), Genova-Sestri Ponente | | | | | |

| Geniere | GE | Soldati 1a Serie | Destroyer | Odero-Terni-Orlandi (O.T.O.), Livorno | 8/26/1937 | 2/27/1938 | 12/14/1938 | Sunk | 3/1/1943 |

| Ghibli | GH | Orsa 2a Serie | Torpedo Boat | Navalmeccanica, Castellammare | 8/30/1941 | 2/28/1943 | 7/24/1943 | Captured | 9/9/1943 |

| Giacinto Carini | | La Masa | Destroyer | Odero-Terni-Orlandi (O.T.O.), Genova-Sestri Ponente | | | | | |

| Giacomo Medici | | La Masa | Destroyer | Odero-Terni-Orlandi (O.T.O.), Genova-Sestri Ponente | | | | | |

| Giada | GD | Platino | Submarine – Coastal | Cantieri Riuniti dell’Adriatico (C.R.D.A.), Monfalcone | 10/16/1940 | 6/10/1941 | 12/8/1941 | Removed from Service | 9/9/1943 |

| Giosue’ Carducci | CD | Oriani | Destroyer | Odero-Terni-Orlandi (O.T.O.), Livorno | 2/5/1936 | 10/28/1936 | 11/1/1937 | Sunk | 4/28/1941 |

| Giovanni Acerbi | | Sirtori | Destroyer | Odero-Terni-Orlandi (O.T.O.), Genova-Sestri Ponente | | | | | |

| Giovanni Berta | | Giuseppe Biglieri | Minesweeper | Schiffbau G.S., Bremerhaven | | | | | |

| Giovanni Da Verazzano | DV | Navigatori | Destroyer | Cantieri Navali del Quarnaro (C.N.Q.), Fiume | 8/17/1927 | 12/15/1928 | 7/25/1930 | Sunk | 10/19/1942 |

| Giovanni dalle Bande Nere | | Condottieri tipo Di Giussano | Cruiser – Light | Navalmeccanica, Castellammare | 10/31/1928 | 4/27/1930 | 4/1/1931 | Sunk | 4/1/1942 |

| Giovanni Nicotera | NC | Sella | Destroyer | Pattison, Napoli | 5/6/1925 | 6/24/1926 | 1/8/1927 | Transferred | 3/1/1940 |

| Giulio Cesare | RI | Osvetnik | Submarine – Coastal | Loires, Nantes (France) | | 1/14/1929 | 4/1/1941 | Scuttled | 8/9/1943 |

| Giulio Germanico | | Capitani Romani | Cruiser – Light | Odero-Terni-Orlandi (O.T.O.), Livorno | 4/3/1939 | 7/26/1941 | 11/9/1943 | | |

| Giuseppe Biglieri | | Giuseppe Biglieri | Minesweeper | Schiffbau G.S., Bremerhaven | | | | | |

| Giuseppe Cesare Abba | | Rosolino Pilo | Destroyer | Odero-Terni-Orlandi (O.T.O.), Genova-Sestri Ponente | | | | | |

| Giuseppe Dezza | | Rosolino Pilo | Destroyer | Odero-Terni-Orlandi (O.T.O.), Genova-Sestri Ponente | | | | Captured | 9/8/1943 |

| Giuseppe Finzi | | Cavour | Battleship | Cantieri del Tirreno (C.T.), Genova-Riva Trigoso | 10/1/1933 | 10/1/1937 | 6/2/1937 | Removed from Service | 2/15/1945 |

| Giuseppe Garibaldi | | Condottieri tipo Duca degli Abruzzi | Cruiser – Light | Cantieri Riuniti dell’Adriatico (C.R.D.A.), Monfalcone | 1/12/1933 | 4/21/1936 | 12/20/1937 | Removed from Service | 5/1/1961 |

| Giuseppe La Farina | | La Masa | Destroyer | Odero-Terni-Orlandi (O.T.O.), Genova-Sestri Ponente | | | | | |

| Giuseppe La Masa | | La Masa | Destroyer | Odero-Terni-Orlandi (O.T.O.), Genova-Sestri Ponente | | | | | |

| Giuseppe Missori | | Rosolino Pilo | Destroyer | Odero-Terni-Orlandi (O.T.O.), Genova-Sestri Ponente | | | | Captured | 9/8/1943 |

| Giuseppe Sirtori | | Sirtori | Destroyer | Odero-Terni-Orlandi (O.T.O.), Genova-Sestri Ponente | | | | | |

| Gladio | | Ariete | Torpedo Boat | Cantieri Riuniti dell’Adriatico (C.R.D.A.), Monfalcone | 1/9/1943 | 6/15/1943 | 1/8/1944 | Captured | 9/9/1943 |

| Glauco | GU | Glauco | Submarine – Oceanic | Cantieri Riuniti dell’Adriatico (C.R.D.A.), Monfalcone | 10/10/1933 | 1/5/1935 | 9/20/1935 | Scuttled | 6/27/1941 |

| Gondar | GO | Adua | Submarine – Coastal | Odero-Terni-Orlandi (O.T.O.), Muggiano (La Spezia) | 2/1/1936 | 9/13/1936 | 11/14/1936 | Scuttled | 9/30/1940 |

| Gorgo | GG | Tritone | Submarine – Coastal | Cantieri Riuniti dell’Adriatico (C.R.D.A.), Monfalcone | 5/15/1941 | 1/30/1942 | 11/11/1942 | Sunk | 5/21/1943 |

| Gorizia | | Zara | Cruiser – Heavy | Odero-Terni-Orlandi (O.T.O.), Livorno | 3/17/1930 | 12/28/1930 | 12/23/1931 | Captured | 9/8/1943 |

| Granatiere | GN | Soldati 1a Serie | Destroyer | Cantiere Navale Riuniti (C.N.R.) Ancona | 4/5/1937 | 4/24/1938 | 2/1/1939 | Removed from Service | 7/1/1958 |

| Granito | GR | Platino | Submarine – Coastal | Cantieri Riuniti dell’Adriatico (C.R.D.A.), Monfalcone | 11/9/1940 | 8/5/1941 | 3/31/1942 | Sunk | 11/9/1942 |

| Grecale | GR | Maestrale | Destroyer | Cantiere Navale Riuniti (C.N.R.) Ancona | 9/25/1931 | 6/17/1934 | 11/15/1934 | Removed from Service | 5/31/1964 |

| Grillo | C28 | Gabbiano | Corvette | Navalmeccanica, Castellammare | 6/22/1942 | 3/21/1943 | | Captured | 9/9/1943 |

| Gronco | | Tritone | Submarine – Coastal | Odero-Terni-Orlandi (O.T.O.), Muggiano (La Spezia) | 5/15/1941 | 1/30/1942 | 11/11/1942 | Scuttled | 9/9/1943 |

| Groppo | GP | Orsa 2a Serie | Torpedo Boat | Navalmeccanica, Castellammare | 6/18/1941 | 4/19/1942 | 8/31/1942 | Sunk | 5/25/1943 |

| Gru | C 18 | Gabbiano | Corvette | Ansaldo, Sestri Levante | 7/6/1942 | 12/23/1942 | 4/29/1943 | | |

| Guglielmo Marconi | FZ | Calvi | Submarine – Oceanic | Odero-Terni-Orlandi (O.T.O.), Muggiano (La Spezia) | 8/1/1932 | 6/29/1935 | 1/8/1936 | Sunk | 9/8/1943 |

| Guglielmotti | GI | Brin | Submarine – Oceanic | Tosi, Taranto | 12/3/1936 | 9/11/1938 | 10/12/1938 | Sunk | 3/17/1942 |

| H1 | | Holland | Submarine – Coastal | Electric Boat Company, (Canada) | 1/1/1916 | 1/1/1916 | | | |

| H2 | | Holland | Submarine – Coastal | Electric Boat Company, (Canada) | 1/1/1916 | 1/1/1916 | | | |

| H4 | | Holland | Submarine – Coastal | Electric Boat Company, (Canada) | 1/1/1916 | 1/1/1917 | | | |

| H6 | | Holland | Submarine – Coastal | Electric Boat Company, (Canada) | 1/1/1916 | 1/1/1916 | | | |

| H8 | | Holland | Submarine – Coastal | Electric Boat Company, (Canada) | 1/1/1916 | 1/1/1916 | | | |

| Ibis | C 17 | Gabbiano | Corvette | Ansaldo, Sestri Levante | 6/18/1942 | 12/12/1942 | 4/3/1943 | | |

| Impavido | IM | Orsa 2a Serie | Torpedo Boat | Cantieri del Tirreno (C.T.), Genova-Riva Trigoso | 8/15/1941 | 2/24/1943 | 4/30/1943 | Captured | 9/16/1943 |

| Impero | | Littorio | Battleship | Ansaldo, Sestri Levante | 5/14/1938 | 11/15/1940 | | | |

| Impetuoso | IP | Orsa 2a Serie | Torpedo Boat | Cantieri del Tirreno (C.T.), Genova-Riva Trigoso | 8/15/1941 | 4/20/1943 | 6/7/1943 | Scuttled | 9/11/1943 |

| Indomito | ID | Orsa 2a Serie | Torpedo Boat | Cantieri del Tirreno (C.T.), Genova-Riva Trigoso | 1/10/1942 | 7/6/1943 | 8/4/1943 | | |

| Intrepido | IT | Orsa 2a Serie | Torpedo Boat | Cantieri del Tirreno (C.T.), Genova-Riva Trigoso | 1/31/1942 | 9/8/1943 | 1/16/1944 | Captured | 9/9/1943 |

| Ippolito Nievo | | Rosolino Pilo | Destroyer | Odero-Terni-Orlandi (O.T.O.), Genova-Sestri Ponente | | | | Removed from Service | 1/1/1938 |

| Iride | IR | Perla | Submarine – Coastal | Odero-Terni-Orlandi (O.T.O.), Muggiano (La Spezia) | 9/3/1935 | 7/30/1936 | 11/6/1936 | Sunk | 8/22/1939 |

| Jalea | IA | Argonauta | Submarine – Coastal | Odero-Terni-Orlandi (O.T.O.), Muggiano (La Spezia) | 1/20/1930 | 6/15/1932 | 3/16/1933 | Removed from Service | 9/9/1942 |

| Jantina | IN | Argonauta | Submarine – Coastal | Odero-Terni-Orlandi (O.T.O.), Muggiano (La Spezia) | 1/20/1930 | 5/16/1932 | 3/1/1933 | Sunk | 7/5/1940 |

| Lafolè | LF | Adua | Submarine – Coastal | Odero-Terni-Orlandi (O.T.O.), Muggiano (La Spezia) | 6/30/1937 | 4/10/1938 | 8/13/1938 | Sunk | 10/20/1939 |

| Lampo | LP | Dardo 2a Serie | Destroyer | Partenopei, Napoli | 1/30/1930 | 7/26/1931 | 8/13/1932 | Sunk | 4/30/1943 |

| Lancia | | Ariete | Torpedo Boat | Cantieri Riuniti dell’Adriatico (C.R.D.A.), Monfalcone | 3/24/1943 | 5/7/1944 | 9/7/1944 | Captured | 9/9/1943 |

| Lanciere | LN | Soldati 1a Serie | Destroyer | Cantieri del Tirreno (C.T.), Genova-Riva Trigoso | 2/1/1937 | 12/18/1938 | 4/25/1939 | Wrecked | 3/23/1942 |

| Lanzerotto Maloncello | MO | Navigatori | Destroyer | Ansaldo, Sestri Levante | 8/30/1927 | 3/14/1929 | 1/18/1930 | Sunk | 3/24/1943 |

| Legionario | LG | Soldati 2a Serie | Destroyer | Odero-Terni-Orlandi (O.T.O.), Livorno | 10/21/1940 | 4/16/1941 | 3/1/1942 | Transferred | 8/15/1948 |

| Legnano | | Ostia | Mine Layer | Cantiere Navale Riuniti (C.N.R.) Ancona | 1/1/1925 | 1/1/1926 | | | |

| Legnano | | Ostia | Minelayer | Cantiere Navale Riuniti (C.N.R.) Ancona | | | | | |

| Leonardo Da Vinci | MN | Marconi | Submarine – Oceanic | Cantieri Riuniti dell’Adriatico (C.R.D.A.), Monfalcone | 9/19/1938 | 7/30/1939 | 2/8/1940 | Sunk | 10/28/1941 |

| Leone | LE | Leone | Destroyer | Ansaldo, Sestri Levante | 11/23/1921 | 10/1/1923 | 7/1/1923 | Wrecked | 4/1/1941 |

| Leone Pancaldo | PN | Navigatori | Destroyer | Cantieri del Tirreno (C.T.), Genova-Riva Trigoso | 7/7/1927 | 2/5/1929 | 11/30/1929 | Sunk | 5/29/1942 |

| Lepanto | | Ostia | Minelayer | Cantiere Navale Riuniti (C.N.R.) Ancona | | | | | |

| Lepanto | | Ostia | Mine Layer | Cantiere Navale Riuniti (C.N.R.) Ancona | 1/1/1925 | 1/1/1925 | | | |

| Libeccio | LI | Maestrale | Destroyer | Cantieri del Tirreno (C.T.), Genova-Riva Trigoso | 9/29/1931 | 7/4/1934 | 11/23/1934 | Sunk | 11/9/1941 |

| Libellula | C 32 | Gabbiano | Corvette | Navalmeccanica, Castellammare | 12/3/1942 | | | | |

| Libra | LB | Spica tipo Alcione | Torpedo Boat | Cantieri Navali del Quarnaro (C.N.Q.), Fiume | 12/7/1936 | 10/3/1937 | 1/19/1938 | | |

| Lince | LC | Spica tipo Alcione | Torpedo Boat | Cantieri Navali del Quarnaro (C.N.Q.), Fiume | 12/7/1936 | 1/15/1938 | 4/1/1938 | Sunk | 8/28/1943 |

| Lira | LR | Spica tipo Alcione | Torpedo Boat | Cantieri Navali del Quarnaro (C.N.Q.), Fiume | 12/7/1936 | 9/12/1937 | 1/1/1938 | Scuttled | 9/9/1943 |

| Littorio | | Littorio | Battleship | Ansaldo, Sestri Levante | 10/28/1934 | 8/22/1937 | 5/6/1940 | Removed from Service | 6/1/1948 |

| Lubiana (ex Ljubljana) | | Sebenico | Destroyer | Yarrow, Glasgow | | | | | |

| Luca Tarigo | TA | Navigatori | Destroyer | Ansaldo, Sestri Levante | 8/30/1927 | 12/9/1928 | 11/16/1929 | Sunk | 4/16/1941 |

| Lucciola | C 27 | Gabbiano | Corvette | Navalmeccanica, Castellammare | 6/22/1942 | 3/21/1943 | | Scuttled | 9/13/1943 |

| Luciano Manara | | Marconi | Submarine – Oceanic | Cantieri Riuniti dell’Adriatico (C.R.D.A.), Monfalcone | 9/19/1938 | 9/16/1939 | 3/8/1940 | Sunk | 5/23/1943 |

| Luigi Cadorna | | Condottieri tipo Cadorna | Cruiser – Light | Cantieri Riuniti dell’Adriatico (C.R.D.A.), Monfalcone | 9/19/1930 | 9/30/1931 | 8/11/1933 | Removed from Service | 5/1/1951 |

| Luigi di Savoia Duca degli Abruzzi | | Condottieri tipo Duca degli Abruzzi | Cruiser – Light | Odero-Terni-Orlandi (O.T.O.), Muggiano (La Spezia) | 12/28/1933 | 4/21/1936 | 12/1/1937 | Removed from Service | 5/1/1961 |

| Luigi Torelli | MR | Bandiera | Submarine – Medium Range | Cantieri Riuniti dell’Adriatico (C.R.D.A.), Monfalcone | 2/18/1928 | 10/5/1929 | 9/9/1930 | Stricken | 9/10/1943 |

| Lupo | LP (LU) | Spica tipo Alcione | Torpedo Boat | Cantieri Navali del Quarnaro (C.N.Q.), Fiume | 12/7/1936 | 11/7/1937 | 2/28/1938 | Sunk | 12/2/1942 |

| Macallè | | Adua | Submarine – Coastal | Odero-Terni-Orlandi (O.T.O.), Muggiano (La Spezia) | 3/1/1936 | 10/29/1936 | 3/1/1937 | Sunk | 6/15/1940 |

| Maestrale | MA | Maestrale | Destroyer | Cantiere Navale Riuniti (C.N.R.) Ancona | 9/25/1931 | 4/5/1934 | 9/2/1934 | Scuttled | 9/9/1943 |

| Maggiolino | C 60 | Gabbiano | Corvette | Navalmeccanica, Castellammare | | | | | |

| Maggiore Baracca | BG | Marconi | Submarine – Oceanic | Odero-Terni-Orlandi (O.T.O.), Muggiano (La Spezia) | 3/1/1939 | 4/21/1940 | 7/10/1940 | Sunk | 9/8/1941 |

| Malachite | MH | Perla | Submarine – Coastal | Odero-Terni-Orlandi (O.T.O.), Muggiano (La Spezia) | 8/31/1935 | 7/15/1936 | 1/6/1936 | Sunk | 2/9/1943 |

| Maleda (ex Mljet) | | Arbe | Minelayer | Kraljevica, Jugoslavia | | | | | |

| Mameli | MM | Mameli | Submarine – Medium Range | Tosi, Taranto | 8/17/1925 | 12/9/1926 | 1/20/1929 | Stricken | 9/9/1943 |

| Marangone | C 52 | Gabbiano | Corvette | Ansaldo, Sestri Levante | 3/15/1943 | 9/16/1943 | 8/16/1944 | Captured | 9/9/1943 |

| Marcantonio Bragadin | | Marconi | Submarine – Oceanic | Odero-Terni-Orlandi (O.T.O.), Muggiano (La Spezia) | 2/15/1939 | 1/6/1940 | 5/15/1940 | Captured | 9/8/1943 |

| Marcantonio Colonna | BG | Bragadin | Submarine – Minelaying | Tosi, Taranto | 2/2/1927 | 7/21/1929 | 11/16/1931 | Stricken | 9/9/1943 |

| Marcello | ML | Marcello | Submarine – Oceanic | Cantieri Riuniti dell’Adriatico (C.R.D.A.), Monfalcone | 1/4/1937 | 9/20/1937 | 3/5/1938 | Sunk | 2/22/1941 |

| Marea | MA | Tritone | Submarine – Coastal | Cantieri Riuniti dell’Adriatico (C.R.D.A.), Monfalcone | 12/1/1941 | 12/10/1942 | 5/7/1943 | Removed from Service | 9/9/1943 |

| Mario Sonzini | | Giuseppe Biglieri | Minesweeper | Schiffbau G.S., Bremerhaven | | | | | |

| MAS 1D (ex TC 1) | | Thornycroft 55 | Motor Torpedo Boat | Thornycroft, Londra | | | | | |

| MAS 204 | | Baglietto 12 ton | Motor Torpedo Boat | Baglietto, Varazze | | 4/12/1918 | | Scuttled | 4/8/1941 |

| MAS 206 | | Baglietto 12 ton | Motor Torpedo Boat | Baglietto, Varazze | | 6/14/1918 | | Scuttled | 4/8/1941 |

| MAS 210 | | Baglietto 12 ton | Motor Torpedo Boat | Baglietto, Varazze | | 8/3/1918 | | Scuttled | 4/8/1941 |

| MAS 213 | | Baglietto 12 ton | Motor Torpedo Boat | Baglietto, Varazze | | 8/19/1918 | | Scuttled | 4/8/1941 |

| MAS 216 | | Baglietto 12 ton | Motor Torpedo Boat | Baglietto, Varazze | | 9/16/1918 | | Scuttled | 4/8/1941 |

| MAS 2D (ex TC 2) | | Thornycroft 55 | Motor Torpedo Boat | Thornycroft, Londra | | | | | |

| MAS 423 | | S.V.A.N velocissimo da 13 tonnellate | Motor Torpedo Boat | Societa Veneziana Automobili Navali (S.V.A.N.), Venezia | | | | | |

| MAS 424 | | Tipo Velocissimo “500” 1a Serie Sperimentale | Motor Torpedo Boat | Baglietto, Varazze | | | | | |

| MAS 426 | | S.V.A.N velocissimo da 13 tonnellate | Motor Torpedo Boat | Societa Veneziana Automobili Navali (S.V.A.N.), Venezia | | | | | |

| MAS 430 | | S.V.A.N velocissimo da 13 tonnellate | Motor Torpedo Boat | Societa Veneziana Automobili Navali (S.V.A.N.), Venezia | | | | | |

| MAS 431 | | Baglietto 1931 | Motor Torpedo Boat | Baglietto, Varazze | | | | | |

| MAS 432 | | S.V.A.N velocissimo da 13 tonnellate | Motor Torpedo Boat | Societa Veneziana Automobili Navali (S.V.A.N.), Venezia | | | | | |

| MAS 433 | | S.V.A.N velocissimo da 13 tonnellate | Motor Torpedo Boat | Societa Veneziana Automobili Navali (S.V.A.N.), Venezia | | | | | |

| MAS 434 | | S.V.A.N velocissimo da 13 tonnellate | Motor Torpedo Boat | Societa Veneziana Automobili Navali (S.V.A.N.), Venezia | | | | | |

| MAS 437 | | S.V.A.N velocissimo diesel | Motor Torpedo Boat | Societa Veneziana Automobili Navali (S.V.A.N.), Venezia | | | | | |

| MAS 438 | | Baglietto 1934 | Motor Torpedo Boat | Baglietto, Varazze | | | | | |

| MAS 439 | | Baglietto 1934 | Motor Torpedo Boat | Baglietto, Varazze | | | | | |

| MAS 440 | | Baglietto 1934 | Motor Torpedo Boat | Baglietto, Varazze | | | | | |

| MAS 441 | | Baglietto 1934 | Motor Torpedo Boat | Baglietto, Varazze | | | | | |

| MAS 451 | | Tipo Biglietto Velocissimo | Motor Torpedo Boat | Picchiotto, Limite d’Arno | | | | | |

| MAS 452 | | Tipo Biglietto Velocissimo | Motor Torpedo Boat | Picchiotto, Limite d’Arno | | | | | |

| MAS 501 | | Tipo Velocissimo “500” 1a Serie | Motor Torpedo Boat | Picchiotto, Limite d’Arno | | | | | |

| MAS 502 | | Tipo Velocissimo “500” 1a Serie | Motor Torpedo Boat | Picchiotto, Limite d’Arno | | | | | |

| MAS 503 | | Tipo Velocissimo “500” 1a Serie | Motor Torpedo Boat | Picchiotto, Limite d’Arno | | | | | |

| MAS 504 | | Tipo Velocissimo “500” 1a Serie | Motor Torpedo Boat | Picchiotto, Limite d’Arno | | | | | |

| MAS 505 | | Tipo Velocissimo “500” 1a Serie | Motor Torpedo Boat | Picchiotto, Limite d’Arno | | | | | |

| MAS 507 | | Tipo Velocissimo “500” 1a Serie | Motor Torpedo Boat | Picchiotto, Limite d’Arno | | | | | |

| MAS 509 | | Tipo Velocissimo “500” 1a Serie | Motor Torpedo Boat | Picchiotto, Limite d’Arno | | | | | |

| MAS 510 | | Tipo Velocissimo “500” 1a Serie | Motor Torpedo Boat | Picchiotto, Limite d’Arno | | | | | |

| MAS 512 | | Tipo Velocissimo “500” 1a Serie | Motor Torpedo Boat | Picchiotto, Limite d’Arno | | | | | |

| MAS 513 | | Tipo Velocissimo “500” 1a Serie | Motor Torpedo Boat | Picchiotto, Limite d’Arno | | | | | |

| MAS 514 | | Tipo Velocissimo “500” 1a Serie | Motor Torpedo Boat | Picchiotto, Limite d’Arno | | | | | |

| MAS 515 | | Tipo Velocissimo “500” 1a Serie | Motor Torpedo Boat | Picchiotto, Limite d’Arno | | | | | |

| MAS 516 | | Tipo Velocissimo “500” 1a Serie | Motor Torpedo Boat | Picchiotto, Limite d’Arno | | | | | |

| MAS 517 | | Tipo Velocissimo “500” 1a Serie | Motor Torpedo Boat | Picchiotto, Limite d’Arno | | | | | |

| MAS 518 | | Tipo Velocissimo “500” 1a Serie | Motor Torpedo Boat | Picchiotto, Limite d’Arno | | | | | |

| MAS 519 | | Tipo Velocissimo “500” 1a Serie | Motor Torpedo Boat | Celli, Venezia | | | | | |

| MAS 520 | | Tipo Velocissimo “500” 1a Serie | Motor Torpedo Boat | Celli, Venezia | | | | | |

| MAS 521 | | Tipo Velocissimo “500” 1a Serie | Motor Torpedo Boat | Celli, Venezia | | | | | |

| MAS 522 | | Tipo Velocissimo “500” 1a Serie | Motor Torpedo Boat | Celli, Venezia | | | | | |

| MAS 523 | | Tipo Velocissimo “500” 1a Serie | Motor Torpedo Boat | Societa Veneziana Automobili Navali (S.V.A.N.), Venezia | | | | | |

| MAS 524 | | Tipo Velocissimo “500” 1a Serie | Motor Torpedo Boat | Societa Veneziana Automobili Navali (S.V.A.N.), Venezia | | | | | |

| MAS 525 | | Tipo Velocissimo “500” 2a Serie | Motor Torpedo Boat | Cantieri Riuniti dell’Adriatico (C.R.D.A.), Monfalcone | | | | | |

| MAS 526 | | Tipo Velocissimo “500” 2a Serie | Motor Torpedo Boat | Baglietto, Varazze | | | | | |

| MAS 527 | | Tipo Velocissimo “500” 2a Serie | Motor Torpedo Boat | Baglietto, Varazze | | | | | |

| MAS 528 | | Tipo Velocissimo “500” 2a Serie | Motor Torpedo Boat | Baglietto, Varazze | | | | | |

| MAS 529 | | Tipo Velocissimo “500” 2a Serie | Motor Torpedo Boat | Baglietto, Varazze | | | | | |

| MAS 530 | | Tipo Velocissimo “500” 2a Serie | Motor Torpedo Boat | Baglietto, Varazze | | | | | |

| MAS 531 | | Tipo Velocissimo “500” 2a Serie | Motor Torpedo Boat | Baglietto, Varazze | | | | | |

| MAS 532 | | Tipo Velocissimo “500” 2a Serie | Motor Torpedo Boat | Baglietto, Varazze | | | | | |

| MAS 533 | | Tipo Velocissimo “500” 2a Serie | Motor Torpedo Boat | Baglietto, Varazze | | | | | |

| MAS 534 | | Tipo Velocissimo “500” 2a Serie | Motor Torpedo Boat | Baglietto, Varazze | | | | | |

| MAS 535 | | Tipo Velocissimo “500” 2a Serie | Motor Torpedo Boat | Baglietto, Varazze | | | | | |

| MAS 536 | | Tipo Velocissimo “500” 2a Serie | Motor Torpedo Boat | Picchiotto, Limite d’Arno | | | | | |

| MAS 537 | | Tipo Velocissimo “500” 2a Serie | Motor Torpedo Boat | Picchiotto, Limite d’Arno | | | | | |

| MAS 538 | | Tipo Velocissimo “500” 2a Serie | Motor Torpedo Boat | Picchiotto, Limite d’Arno | | | | | |

| MAS 539 | | Tipo Velocissimo “500” 2a Serie | Motor Torpedo Boat | Picchiotto, Limite d’Arno | | | | | |

| MAS 540 | | Tipo Velocissimo “500” 2a Serie | Motor Torpedo Boat | Celli, Venezia | | | | | |

| MAS 541 | | Tipo Velocissimo “500” 2a Serie | Motor Torpedo Boat | Celli, Venezia | | | | | |

| MAS 542 | | Tipo Velocissimo “500” 2a Serie | Motor Torpedo Boat | Celli, Venezia | | | | | |

| MAS 543 | | Tipo Velocissimo “500” 2a Serie | Motor Torpedo Boat | Celli, Venezia | | | | | |

| MAS 544 | | Tipo Velocissimo “500” 2a Serie | Motor Torpedo Boat | Celli, Venezia | | | | | |

| MAS 545 | | Tipo Velocissimo “500” 2a Serie | Motor Torpedo Boat | Picchiotto, Limite d’Arno | | | | | |

| MAS 546 | | Tipo Velocissimo “500” 2a Serie | Motor Torpedo Boat | Cantieri Riuniti dell’Adriatico (C.R.D.A.), Monfalcone | | | | | |

| MAS 547 | | Tipo Velocissimo “500” 2a Serie | Motor Torpedo Boat | Cantieri Riuniti dell’Adriatico (C.R.D.A.), Monfalcone | | | | | |

| MAS 548 | | Tipo Velocissimo “500” 2a Serie | Motor Torpedo Boat | Cantieri Riuniti dell’Adriatico (C.R.D.A.), Monfalcone | | | | | |

| MAS 549 | | Tipo Velocissimo “500” 2a Serie | Motor Torpedo Boat | Cantieri Riuniti dell’Adriatico (C.R.D.A.), Monfalcone | | | | | |

| MAS 550 | | Tipo Velocissimo “500” 2a Serie | Motor Torpedo Boat | Cantieri Riuniti dell’Adriatico (C.R.D.A.), Monfalcone | | | | | |

| MAS 551 | | Tipo Velocissimo “500” 3a Serie | Motor Torpedo Boat | C.N.A., Roma | | | | | |

| MAS 552 | | Tipo Velocissimo “500” 3a Serie | Motor Torpedo Boat | Cantieri Riuniti dell’Adriatico (C.R.D.A.), Monfalcone | | | | | |

| MAS 553 | | Tipo Velocissimo “500” 3a Serie | Motor Torpedo Boat | Cantieri Riuniti dell’Adriatico (C.R.D.A.), Monfalcone | | | | | |

| MAS 554 | | Tipo Velocissimo “500” 3a Serie | Motor Torpedo Boat | Cantieri Riuniti dell’Adriatico (C.R.D.A.), Monfalcone | | | | | |

| MAS 555 | | Tipo Velocissimo “500” 3a Serie | Motor Torpedo Boat | Picchiotto, Limite d’Arno | | | | | |

| MAS 556 | | Tipo Velocissimo “500” 3a Serie | Motor Torpedo Boat | Picchiotto, Limite d’Arno | | | | | |

| MAS 557 | | Tipo Velocissimo “500” 3a Serie | Motor Torpedo Boat | Picchiotto, Limite d’Arno | | | | | |

| MAS 558 | | Tipo Velocissimo “500” 3a Serie | Motor Torpedo Boat | Celli, Venezia | | | | | |

| MAS 559 | | Tipo Velocissimo “500” 3a Serie | Motor Torpedo Boat | Celli, Venezia | | | | | |

| MAS 560 | | Tipo Velocissimo “500” 3a Serie | Motor Torpedo Boat | Celli, Venezia | | | | | |

| MAS 561 | | Tipo Velocissimo “500” 3a Serie | Motor Torpedo Boat | Baglietto, Varazze | | | | | |

| MAS 562 | | Tipo Velocissimo “500” 3a Serie | Motor Torpedo Boat | Baglietto, Varazze | | | | | |

| MAS 563 | | Tipo Velocissimo “500” 3a Serie | Motor Torpedo Boat | Baglietto, Varazze | | | | | |

| MAS 564 | | Tipo Velocissimo “500” 3a Serie | Motor Torpedo Boat | Baglietto, Varazze | | | | | |

| MAS 566 | | Tipo Velocissimo “500” 4a Serie | Motor Torpedo Boat | Baglietto, Varazze | | | | | |

| MAS 567 | | Tipo Velocissimo “500” 4a Serie | Motor Torpedo Boat | Baglietto, Varazze | | | | | |

| MAS 568 | | Tipo Velocissimo “500” 4a Serie | Motor Torpedo Boat | Baglietto, Varazze | | | | | |

| MAS 569 | | Tipo Velocissimo “500” 4a Serie | Motor Torpedo Boat | Baglietto, Varazze | | | | | |

| MAS 570 | | Tipo Velocissimo “500” 4a Serie | Motor Torpedo Boat | Baglietto, Varazze | | | | | |

| MAS 571 | | Tipo Velocissimo “500” 4a Serie | Motor Torpedo Boat | Picchiotto, Limite d’Arno | | | | | |

| MAS 572 | | Tipo Velocissimo “500” 4a Serie | Motor Torpedo Boat | Picchiotto, Limite d’Arno | | | | | |

| MAS 573 | | Tipo Velocissimo “500” 4a Serie | Motor Torpedo Boat | Picchiotto, Limite d’Arno | | | | | |

| MAS 574 | | Tipo Velocissimo “500” 4a Serie | Motor Torpedo Boat | Celli, Venezia | | | | | |

| MAS 575 | | Tipo Velocissimo “500” 4a Serie | Motor Torpedo Boat | Celli, Venezia | | | | | |

| MAS 576 | | Tipo Velocissimo “500” 4a Serie | Motor Torpedo Boat | Celli, Venezia | | | | | |

| Medusa | MU | Argonauta | Submarine – Coastal | Cantieri Riuniti dell’Adriatico (C.R.D.A.), Monfalcone | 11/30/1929 | 12/10/1931 | 10/8/1932 | Sunk | 1/30/1942 |

| Melpomene | C 68 | Gabbiano | Corvette | Cantieri Riuniti dell’Adriatico (C.R.D.A.), Monfalcone | 3/25/1943 | 8/29/1943 | | Captured | 9/9/1943 |

| Meteo | | Abastro | Minesweeper | Neptun, Rostok | | | | | |

| Micca | MC | Micca | Submarine – Minelaying | Tosi, Taranto | 10/15/1931 | 3/31/1935 | 1/10/1935 | Sunk | 7/29/1943 |

| Michele Bianchi | CN | Pisani | Submarine – Medium Range | Cantieri Riuniti dell’Adriatico (C.R.D.A.), Monfalcone | 3/12/1925 | 12/26/2027 | 7/10/1929 | Removed from Service | 6/1/1942 |

| Milazzo | | Ostia | Minelayer | Stabilimento Tecnico Triestino, Trieste | | | | | |

| Milazzo | | Ostia | Mine Layer | Cantieri Riuniti dell’Adriatico (C.R.D.A.), Monfalcone | 1/1/1925 | 1/1/1927 | | | |

| Millelire | MI | Balilla | Submarine – Oceanic | Odero-Terni-Orlandi (O.T.O.), Muggiano (La Spezia) | 10/20/1925 | 9/19/1927 | 8/11/1928 | Removed from Service | 5/15/1941 |

| Minerva | C 42 | Gabbiano | Corvette | Cantieri Riuniti dell’Adriatico (C.R.D.A.), Monfalcone | 4/2/1942 | 11/5/1942 | 2/24/1943 | | |

| Mitragliere | MT | Soldati 2a Serie | Destroyer | Cantiere Navale Riuniti (C.N.R.) Ancona | 10/7/1940 | 9/28/1941 | 2/1/1942 | Transferred | 7/15/1948 |

| Mocenigo | MO | Marcello | Submarine – Oceanic | Cantieri Riuniti dell’Adriatico (C.R.D.A.), Monfalcone | 1/19/1937 | 11/20/1937 | 8/16/1938 | Sunk | 3/14/1941 |

| Monsone | MS | Orsa 2a Serie | Torpedo Boat | Navalmeccanica, Castellammare | 6/18/1941 | 6/7/1942 | 11/28/1942 | Sunk | 3/1/1943 |

| Morosini | MS | Marcello | Submarine – Oceanic | Cantieri Riuniti dell’Adriatico (C.R.D.A.), Monfalcone | 3/2/1937 | 7/28/1938 | 11/11/1938 | Sunk | 8/11/1942 |

| Mozambano | | Curtatone | Destroyer | Orlando, Livorno | 1/1/1920 | 1/1/1922 | 1/1/1923 | | |

| MS 11 | | C.R.D.A. 60 ton 1a Serie | Motor Torpedo Boat | Cantieri Riuniti dell’Adriatico (C.R.D.A.), Monfalcone | | | | | |

| MS 41 (ex Orjen) | | S1 | Motor Torpedo Boat | Lurssen, Vegesak | | | | | |

| MS 51 | | MS 51 | Motor Torpedo Boat | Cantieri Riuniti dell’Adriatico (C.R.D.A.), Monfalcone | 8/6/1942 | 10/14/1942 | 2/15/1943 | Scuttled | 9/9/1943 |

| MS 12 | | C.R.D.A. 60 ton 1a Serie | Motor Torpedo Boat | Cantieri Riuniti dell’Adriatico (C.R.D.A.), Monfalcone | | | | | |

| MS 13 | | C.R.D.A. 60 ton 1a Serie | Motor Torpedo Boat | Cantieri Riuniti dell’Adriatico (C.R.D.A.), Monfalcone | | | | | |

| MS 14 | | C.R.D.A. 60 ton 1a Serie | Motor Torpedo Boat | Cantieri Riuniti dell’Adriatico (C.R.D.A.), Monfalcone | | | | | |

| MS 15 | | C.R.D.A. 60 ton 1a Serie | Motor Torpedo Boat | Cantieri Riuniti dell’Adriatico (C.R.D.A.), Monfalcone | | | | | |

| MS 16 | | C.R.D.A. 60 ton 1a Serie | Motor Torpedo Boat | Cantieri Riuniti dell’Adriatico (C.R.D.A.), Monfalcone | | | | | |

| MS 21 | | C.R.D.A. 60 ton 1a Serie | Motor Torpedo Boat | Cantieri Riuniti dell’Adriatico (C.R.D.A.), Monfalcone | | | | | |

| MS 22 | | C.R.D.A. 60 ton 1a Serie | Motor Torpedo Boat | Cantieri Riuniti dell’Adriatico (C.R.D.A.), Monfalcone | | | | | |

| MS 23 | | C.R.D.A. 60 ton 1a Serie | Motor Torpedo Boat | Cantieri Riuniti dell’Adriatico (C.R.D.A.), Monfalcone | | | | | |

| MS 24 | | C.R.D.A. 60 ton 1a Serie | Motor Torpedo Boat | Cantieri Riuniti dell’Adriatico (C.R.D.A.), Monfalcone | | | | | |

| MS 25 | | C.R.D.A. 60 ton 1a Serie | Motor Torpedo Boat | Cantieri Riuniti dell’Adriatico (C.R.D.A.), Monfalcone | | | | | |

| MS 26 | | C.R.D.A. 60 ton 1a Serie | Motor Torpedo Boat | Cantieri Riuniti dell’Adriatico (C.R.D.A.), Monfalcone | | | | | |

| MS 31 | | C.R.D.A. 60 ton 1a Serie | Motor Torpedo Boat | Cantieri Riuniti dell’Adriatico (C.R.D.A.), Monfalcone | | | | | |

| MS 32 | | C.R.D.A. 60 ton 1a Serie | Motor Torpedo Boat | Cantieri Riuniti dell’Adriatico (C.R.D.A.), Monfalcone | | | | | |

| MS 33 | | C.R.D.A. 60 ton 1a Serie | Motor Torpedo Boat | Cantieri Riuniti dell’Adriatico (C.R.D.A.), Monfalcone | | | | | |

| MS 34 | | C.R.D.A. 60 ton 1a Serie | Motor Torpedo Boat | Cantieri Riuniti dell’Adriatico (C.R.D.A.), Monfalcone | | | | | |

| MS 35 | | C.R.D.A. 60 ton 1a Serie | Motor Torpedo Boat | Cantieri Riuniti dell’Adriatico (C.R.D.A.), Monfalcone | | | | | |

| MS 36 | | C.R.D.A. 60 ton 1a Serie | Motor Torpedo Boat | Cantieri Riuniti dell’Adriatico (C.R.D.A.), Monfalcone | | | | | |

| MS 43 | | Lürssen “S 2” | Motor Torpedo Boat | Lurssen, Vegesak | | | | | |

| MS 44 | | Lürssen “S 2” | Motor Torpedo Boat | Lurssen, Vegesak | | | | | |

| MS 45 | | Lürssen “S 2” | Motor Torpedo Boat | Lurssen, Vegesak | | | | | |

| MS 46 | | Lürssen “S 2” | Motor Torpedo Boat | Lurssen, Vegesak | | | | | |

| MS 51 | | C.R.D.A. 60 ton 2a Serie | Motor Torpedo Boat | Cantieri Riuniti dell’Adriatico (C.R.D.A.), Monfalcone | | | | | |

| MS 52 | | C.R.D.A. 60 ton 2a Serie | Motor Torpedo Boat | Cantieri Riuniti dell’Adriatico (C.R.D.A.), Monfalcone | | | | | |

| MS 53 | | C.R.D.A. 60 ton 2a Serie | Motor Torpedo Boat | Cantieri Riuniti dell’Adriatico (C.R.D.A.), Monfalcone | | | | | |

| MS 54 | | C.R.D.A. 60 ton 2a Serie | Motor Torpedo Boat | Cantieri Riuniti dell’Adriatico (C.R.D.A.), Monfalcone | | | | | |

| MS 55 | | C.R.D.A. 60 ton 2a Serie | Motor Torpedo Boat | Cantieri Riuniti dell’Adriatico (C.R.D.A.), Monfalcone | | | | | |

| MS 56 | | C.R.D.A. 60 ton 2a Serie | Motor Torpedo Boat | Cantieri Riuniti dell’Adriatico (C.R.D.A.), Monfalcone | | | | | |

| MS 61 | | C.R.D.A. 60 ton 2a Serie | Motor Torpedo Boat | Cantieri Riuniti dell’Adriatico (C.R.D.A.), Monfalcone | | | | | |

| MS 62 | | C.R.D.A. 60 ton 2a Serie | Motor Torpedo Boat | Cantieri Riuniti dell’Adriatico (C.R.D.A.), Monfalcone | | | | | |

| MS 63 | | C.R.D.A. 60 ton 2a Serie | Motor Torpedo Boat | Cantieri Riuniti dell’Adriatico (C.R.D.A.), Monfalcone | | | | | |

| MS 64 | | C.R.D.A. 60 ton 2a Serie | Motor Torpedo Boat | Cantieri Riuniti dell’Adriatico (C.R.D.A.), Monfalcone | | | | | |

| MS 65 | | C.R.D.A. 60 ton 2a Serie | Motor Torpedo Boat | Cantieri Riuniti dell’Adriatico (C.R.D.A.), Monfalcone | | | | | |

| MS 66 | | C.R.D.A. 60 ton 2a Serie | Motor Torpedo Boat | Cantieri Riuniti dell’Adriatico (C.R.D.A.), Monfalcone | | | | | |

| MS 71 | | C.R.D.A. 60 ton 2a Serie | Motor Torpedo Boat | Cantieri Riuniti dell’Adriatico (C.R.D.A.), Monfalcone | | | | | |

| MS 72 | | C.R.D.A. 60 ton 2a Serie | Motor Torpedo Boat | Cantieri Riuniti dell’Adriatico (C.R.D.A.), Monfalcone | | | | | |

| MS 73 | | C.R.D.A. 60 ton 2a Serie | Motor Torpedo Boat | Cantieri Riuniti dell’Adriatico (C.R.D.A.), Monfalcone | | | | | |

| MS 74 | | C.R.D.A. 60 ton 2a Serie | Motor Torpedo Boat | Cantieri Riuniti dell’Adriatico (C.R.D.A.), Monfalcone | | | | | |

| MS 75 | | C.R.D.A. 60 ton 2a Serie | Motor Torpedo Boat | Cantieri Riuniti dell’Adriatico (C.R.D.A.), Monfalcone | | | | | |

| MS 76 | | C.R.D.A. 60 ton 2a Serie | Motor Torpedo Boat | Cantieri Riuniti dell’Adriatico (C.R.D.A.), Monfalcone | | | | | |

| Murena | | Tritone | Submarine – Coastal | Odero-Terni-Orlandi (O.T.O.), Muggiano (La Spezia) | 4/1/1942 | 4/11/1943 | 8/25/1943 | Scuttled | 9/9/1943 |

| Muzio Attendolo | | Condottieri tipo Montecuccoli | Cruiser – Light | Cantieri Riuniti dell’Adriatico (C.R.D.A.), Monfalcone | 4/10/1933 | 9/9/1934 | 8/7/1935 | Sunk | 12/4/1942 |

| Naiade | NA | Sirena | Submarine – Coastal | Cantieri Riuniti dell’Adriatico (C.R.D.A.), Monfalcone | 5/9/1931 | 3/27/1933 | 11/16/1933 | Scuttled | 12/14/1940 |

| Nani | NI | Marcello | Submarine – Oceanic | Cantieri Riuniti dell’Adriatico (C.R.D.A.), Monfalcone | 1/15/1937 | 1/16/1938 | 9/5/1938 | Sunk | 1/7/1941 |

| Narvalo | NR | Squalo | Submarine – Medium Range | Cantieri Riuniti dell’Adriatico (C.R.D.A.), Monfalcone | 10/17/1928 | 3/15/1930 | 12/11/1930 | Scuttled | 1/14/1943 |

| Nautilo | | Tritone | Submarine – Coastal | Cantieri Riuniti dell’Adriatico (C.R.D.A.), Monfalcone | 1/3/1942 | 3/20/1943 | 7/26/1943 | Scuttled | 9/9/1943 |

| Nazario Sauro | BH | Marconi | Submarine – Oceanic | Odero-Terni-Orlandi (O.T.O.), Muggiano (La Spezia) | 2/15/1939 | 12/3/1939 | 4/15/1940 | Sunk | 7/5/1941 |

| Neghelli | NG | Adua | Submarine – Coastal | Odero-Terni-Orlandi (O.T.O.), Muggiano (La Spezia) | 2/25/1937 | 11/7/1937 | 2/22/1938 | Sunk | 1/19/1941 |

| Nembo | NB | Turbine | Destroyer | Cantieri del Tirreno (C.T.), Genova-Riva Trigoso | 1/21/1925 | 1/27/1927 | 10/24/1927 | Sunk | 7/20/1940 |

| Nereide | NE | Sirena | Submarine – Coastal | Cantieri Riuniti dell’Adriatico (C.R.D.A.), Monfalcone | 5/30/1931 | 5/25/1933 | 2/17/1934 | Sunk | 7/13/1943 |

| Nichelio | NC | Platino | Submarine – Coastal | Odero-Terni-Orlandi (O.T.O.), Muggiano (La Spezia) | 7/1/1941 | 4/12/1942 | 7/30/1942 | Removed from Service | 9/8/1943 |

| Nicola Fabrizi | SU | Sauro | Destroyer | Odero-Terni-Orlandi (O.T.O.), Genova-Sestri Ponente | 2/9/1924 | 5/12/1926 | 9/23/1926 | Sunk | 4/3/1941 |

| Nicolo’ Zeno | | La Masa | Destroyer | Odero-Terni-Orlandi (O.T.O.), Genova-Sestri Ponente | | | | | |

| Nicoloso Da Recco | ZE | Navigatori | Destroyer | Cantieri Navali del Quarnaro (C.N.Q.), Fiume | 6/5/1927 | 8/12/1928 | 5/27/1930 | Sunk | 9/9/1943 |

| Ondina | ON | Sirena | Submarine – Coastal | Cantieri Riuniti dell’Adriatico (C.R.D.A.), Monfalcone | 7/25/1931 | 12/2/1933 | 9/19/1934 | Scuttled | 7/11/1942 |

| Onice | OC | Perla | Submarine – Coastal | Odero-Terni-Orlandi (O.T.O.), Muggiano (La Spezia) | 8/27/1935 | 6/15/1936 | 9/1/1936 | Stricken | 9/9/1943 |

| Orione | | Orsa 1a Serie | Torpedo Boat | Cantiere Navale Riuniti (C.N.R.) Ancona | 4/27/1936 | 4/21/1937 | 3/31/1938 | | |

| Orsa | | Orsa 1a Serie | Torpedo Boat | Cantiere Navale Riuniti (C.N.R.) Ancona | 4/27/1936 | 3/21/1937 | 3/31/1938 | | |

| Ostia | | Ostia | Mine Layer | Cantieri Riuniti dell’Adriatico (C.R.D.A.), Monfalcone | 1/1/1925 | 1/1/1925 | | | |

| Ostia | | Ostia | Minelayer | Stabilimento Tecnico Triestino, Trieste | | | | | |

| Ostro | OT | Turbine | Destroyer | Ansaldo, Sestri Levante | 4/29/1925 | 1/2/1928 | 10/9/1928 | Sunk | 7/21/1940 |

| Otaria | OA | Glauco | Submarine – Oceanic | Cantieri Riuniti dell’Adriatico (C.R.D.A.), Monfalcone | 11/17/1933 | 3/20/1935 | 10/20/1935 | Stricken | 9/9/1943 |

| Palestro | | Palestro | Destroyer | Orlando, Livorno | | | | | |

| Pallade | PD | Spica tipo Alcione | Torpedo Boat | Societa Anonima Bacini e Scali Napoli, Napoli | 2/13/1937 | 12/19/1937 | 10/5/1938 | Sunk | 8/4/1943 |

| Pantera | PA | Leone | Destroyer | Ansaldo, Sestri Levante | 12/19/1921 | 10/18/1923 | 10/28/1924 | Scuttled | 4/4/1941 |

| Partenope | PN | Spica tipo Alcione | Torpedo Boat | Societa Anonima Bacini e Scali Napoli, Napoli | 1/31/1937 | 2/27/1938 | 11/26/1938 | Sunk | 5/4/1943 |

| Pasman (ex Mosor) | | Arbe | Minelayer | Kraljevica, Jugoslavia | | | | | |

| Pegaso | | Orsa 1a Serie | Torpedo Boat | Societa Anonima Bacini e Scali Napoli, Napoli | 2/15/1936 | 12/8/1936 | 3/30/1938 | Scuttled | 9/11/1943 |

| Pelagosa | | Fasana | Minelayer | Navalmeccanica, Castellammare | | | | | |

| Pellegrino Matteucci | | Pellegrino Matteucci | Minesweeper | Deutsche Werft, Amburgo (Germany) | | | | | |

| Pellegrino Matteucci | | Giuseppe Biglieri | Minesweeper | Schiffbau G.S., Bremerhaven | | | | | |

| Pellicano | C 14 | Gabbiano | Corvette | Societa Anonima Cantieri Cerusa, Genova-Voltri | 1/14/1942 | 2/12/1943 | 3/15/1943 | | |

| Perla | PL | Perla | Submarine – Coastal | Cantieri Riuniti dell’Adriatico (C.R.D.A.), Monfalcone | 8/31/1935 | 5/3/1936 | 7/8/1936 | Captured | 7/9/1942 |

| Persefone | C 40 | Gabbiano | Corvette | Cantieri Riuniti dell’Adriatico (C.R.D.A.), Monfalcone | 3/9/1942 | 9/21/1942 | 11/28/1942 | Scuttled | 9/9/1943 |

| Perseo | PS | Spica tipo Perseo | Torpedo Boat | Cantieri Navali del Quarnaro (C.N.Q.), Fiume | 11/21/1934 | 10/9/1935 | 2/1/1936 | Sunk | 5/4/1943 |

| Pier Capponi | DR | Navigatori | Destroyer | Cantiere Navale Riuniti (C.N.R.) Ancona | 12/14/1927 | 1/5/1930 | 5/20/1930 | Removed from Service | 7/15/1954 |

| Pietro Calvi | CP | Mameli | Submarine – Medium Range | Tosi, Taranto | 8/27/1925 | 6/19/1927 | 1/20/1929 | Sunk | 3/31/1941 |

| Platino | PT | Platino | Submarine – Coastal | Odero-Terni-Orlandi (O.T.O.), Muggiano (La Spezia) | 11/20/1940 | 6/1/1941 | 10/2/1941 | Removed from Service | |

| Pleiadi | PL | Spica tipo Alcione | Torpedo Boat | Societa Anonima Bacini e Scali Napoli, Napoli | 1/4/1937 | 9/5/1937 | 7/4/1938 | Sunk | 10/14/1941 |

| Pola | | Zara | Cruiser – Heavy | Odero-Terni-Orlandi (O.T.O.), Livorno | 3/17/1931 | 12/5/1931 | 12/21/1932 | Sunk | 3/28/1941 |

| Polluce | PV | Spica tipo Alcione | Torpedo Boat | Societa Anonima Bacini e Scali Napoli, Napoli | 2/13/1937 | 10/24/1937 | 8/8/1938 | Sunk | 9/4/1942 |

| Pomona | C 45 | Gabbiano | Corvette | Cantieri Riuniti dell’Adriatico (C.R.D.A.), Monfalcone | 5/16/1942 | 11/18/1942 | 4/4/1943 | | |

| Pompeo Magno | | Capitani Romani | Cruiser – Light | Odero-Terni-Orlandi (O.T.O.), Livorno | 9/23/1939 | 8/24/1941 | 6/4/1943 | Removed from Service | 5/1/1950 |

| Porfido | PO | Platino | Submarine – Coastal | Cantieri Riuniti dell’Adriatico (C.R.D.A.), Monfalcone | 11/9/1940 | 8/23/1941 | 1/24/1942 | Sunk | 12/6/1942 |

| Premuda | | Premuda | Destroyer | Yarrow, Glasgow | | | | | |

| Procellaria | C 12 | Gabbiano | Corvette | Societa Anonima Cantieri Cerusa, Genova-Voltri | 1/14/1942 | 9/4/1942 | 11/29/1942 | | |

| Procione | | Orsa 1a Serie | Torpedo Boat | Societa Anonima Bacini e Scali Napoli, Napoli | 2/15/1936 | 1/31/1937 | 3/30/1938 | Scuttled | 9/9/1943 |

| Provana | PR | Marcello | Submarine – Oceanic | Cantieri Riuniti dell’Adriatico (C.R.D.A.), Monfalcone | 2/3/1937 | 3/16/1938 | 7/25/1938 | Sunk | 6/17/1940 |

| Pugnale | | Ariete | Torpedo Boat | Cantieri Riuniti dell’Adriatico (C.R.D.A.), Monfalcone | 1/9/1943 | 8/1/1943 | 7/7/1944 | Captured | 9/9/1943 |

| Quintino Sella | SE | Sella | Destroyer | Pattison, Napoli | 10/12/1922 | 4/25/1925 | 3/25/1926 | Sunk | 9/11/1943 |

| R.D.12 | | R.D. | Minesweeper | Tosi, Taranto | | | | | |

| R.D.13 | | R.D. | Minesweeper | Poli, Chioggia | | | | | |

| R.D.16 | | R.D. | Minesweeper | Navalmeccanica, Castellammare | | | | | |

| R.D.17 | | R.D. | Minesweeper | Navalmeccanica, Castellammare | | | | | |

| R.D.18 | | R.D. | Minesweeper | Navalmeccanica, Castellammare | | | | | |

| R.D.20 | | R.D. | Minesweeper | Navalmeccanica, Castellammare | | | | | |

| R.D.21 | | R.D. | Minesweeper | Navalmeccanica, Castellammare | | | | | |

| R.D.22 | | R.D. | Minesweeper | Navalmeccanica, Castellammare | | | | | |

| R.D.23 | | R.D. | Minesweeper | Navalmeccanica, Castellammare | | | | | |

| R.D.24 | | R.D. | Minesweeper | Navalmeccanica, Castellammare | | | | | |

| R.D.25 | | R.D. | Minesweeper | Navalmeccanica, Castellammare | | | | | |

| R.D.26 | | R.D. | Minesweeper | Navalmeccanica, Castellammare | | | | | |

| R.D.27 | | R.D. | Minesweeper | Tosi, Taranto | | | | | |

| R.D.28 | | R.D. | Minesweeper | Tosi, Taranto | | | | | |

| R.D.29 | | R.D. | Minesweeper | Tosi, Taranto | | | | | |

| R.D.30 | | R.D. | Minesweeper | Tosi, Taranto | | | | | |

| R.D.31 | | R.D. | Minesweeper | Navalmeccanica, Castellammare | | | | | |

| R.D.32 | | R.D. | Minesweeper | Navalmeccanica, Castellammare | | | | | |

| R.D.33 | | R.D. | Minesweeper | Navalmeccanica, Castellammare | | | | | |

| R.D.34 | | R.D. | Minesweeper | Navalmeccanica, Castellammare | | | | | |

| R.D.35 | | R.D. | Minesweeper | Navalmeccanica, Castellammare | | | | | |

| R.D.36 | | R.D. | Minesweeper | Navalmeccanica, Castellammare | | | | | |

| R.D.37 | | R.D. | Minesweeper | Navalmeccanica, Castellammare | | | | | |

| R.D.38 | | R.D. | Minesweeper | Arsenale Navale, Napoli | | | | | |

| R.D.39 | | R.D. | Minesweeper | Tosi, Taranto | | | | | |

| R.D.40 | | R.D. | Minesweeper | Tosi, Taranto | | | | | |

| R.D.41 | | R.D. | Minesweeper | Tosi, Taranto | | | | | |

| R.D.42 | | R.D. | Minesweeper | Tosi, Taranto | | | | | |

| R.D.43 | | R.D. | Minesweeper | Tosi, Taranto | | | | | |

| R.D.44 | | R.D. | Minesweeper | Tosi, Taranto | | | | | |

| R.D.55 | | R.D. | Minesweeper | Migliardi, Savona | | | | | |

| R.D.56 | | R.D. | Minesweeper | Migliardi, Savona | | | | | |

| R.D.57 | | R.D. | Minesweeper | Migliardi, Savona | | | | | |

| R.D.58 | | R.D.58 | Minesweeper | Danubius, Fiume | | | | | |

| R.D.59 | | R.D.58 | Minesweeper | Danubius, Fiume | | | | | |

| R.D.6 | | R.D. | Minesweeper | Navalmeccanica, Castellammare | | | | | |

| R.D.60 | | R.D.58 | Minesweeper | Danubius, Fiume | | | | | |

| R.D.7 | | R.D. | Minesweeper | Tosi, Taranto | | | | | |

| R10 | | R | Submarine – Transport | Cantieri Riuniti dell’Adriatico (C.R.D.A.), Monfalcone | 2/24/1943 | 7/13/1943 | | Stricken | |

| R11 | | R | Submarine – Transport | Cantieri Riuniti dell’Adriatico (C.R.D.A.), Monfalcone | 3/10/1943 | 7/6/1944 | | Stricken | |

| R12 | | R | Submarine – Transport | Cantieri Riuniti dell’Adriatico (C.R.D.A.), Monfalcone | 5/13/1943 | 9/29/1944 | | Stricken | |

| R3 | | R | Submarine – Transport | Tosi, Taranto | 3/1/1943 | 9/7/1946 | | Stricken | |

| R4 | | R | Submarine – Transport | Tosi, Taranto | 3/1/1943 | 9/30/1946 | | Stricken | |

| R5 | | R | Submarine – Transport | Tosi, Taranto | 3/25/1943 | | | Stricken | |

| R6 | | R | Submarine – Transport | Tosi, Taranto | 3/25/1943 | | | Stricken | |

| R7 | | R | Submarine – Transport | Cantieri Riuniti dell’Adriatico (C.R.D.A.), Monfalcone | 3/1/1943 | 10/31/1943 | | Stricken | |

| R8 | | R | Submarine – Transport | Cantieri Riuniti dell’Adriatico (C.R.D.A.), Monfalcone | 3/1/1943 | 12/28/1943 | | Stricken | |

| R9 | | R | Submarine – Transport | Cantieri Riuniti dell’Adriatico (C.R.D.A.), Monfalcone | 3/6/1943 | 2/27/1944 | | Stricken | |

| Raimondo Montecuccoli | | Condottieri tipo Montecuccoli | Cruiser – Light | Ansaldo, Sestri Levante | 10/1/1931 | 8/2/1934 | 6/30/1935 | | 6/1/1964 |

| Reginaldo Giuliani | CV | Calvi | Submarine – Oceanic | Odero-Terni-Orlandi (O.T.O.), Muggiano (La Spezia) | 7/20/1932 | 3/3/1935 | 10/16/1935 | Scuttled | 7/15/1942 |

| Remo | RE | R | Submarine – Transport | Tosi, Taranto | 7/21/1942 | 3/21/1943 | 6/19/1943 | Sunk | 7/15/1943 |

| Renna | C 24 | Gabbiano | Corvette | Odero-Terni-Orlandi (O.T.O.), Livorno | 5/31/1942 | 12/5/1942 | | Captured | 9/9/1943 |

| Rigel | | Ariete | Torpedo Boat | Ansaldo, Sestri Levante | 7/15/1942 | 5/22/1943 | 1/23/1944 | Captured | 9/9/1943 |

| Roma | | Littorio | Battleship | Cantieri Riuniti dell’Adriatico (C.R.D.A.), Monfalcone | 9/18/1938 | 6/9/1940 | 6/14/1942 | Sunk | 9/9/1943 |

| Romolo | RO | R | Submarine – Transport | Tosi, Taranto | 4/5/1942 | 3/28/1943 | 6/19/1943 | Sunk | 7/18/1943 |

| Rosolino Pilo | | Rosolino Pilo | Destroyer | Odero-Terni-Orlandi (O.T.O.), Genova-Sestri Ponente | 1/1/1913 | 1/1/1915 | 1/1/1915 | | |

| Rubino | RU | Sirena | Submarine – Coastal | Cantieri Navali del Quarnaro (C.N.Q.), Fiume | 9/26/1931 | 3/29/1933 | 3/21/1934 | Sunk | 6/29/1940 |

| Ruggiero Settimo | GN | Liuzzi | Submarine – Oceanic | Tosi, Taranto | 3/13/1939 | 12/3/1939 | 2/3/1940 | Captured | 9/8/1943 |

| S 1 | | S | Submarine – Coastal | Danziger Werft Danzig (Germany) | 8/14/1942 | 3/11/1943 | 6/26/1943 | Captured | |

| S 2 | | S | Submarine – Coastal | Schichau, Danzig (Germany) | 7/15/1942 | | 7/4/1943 | Captured | |

| S 3 | | S | Submarine – Coastal | Schichau, Danzig (Germany) | 8/19/1942 | | 7/17/1943 | Captured | |

| S 4 | | S | Submarine – Coastal | Danziger Werft Danzig (Germany) | 9/14/1942 | | 7/14/1943 | Captured | |

| S 5 | | S | Submarine – Coastal | Schichau, Danzig (Germany) | 8/20/1942 | | 7/31/1943 | Captured | |

| S 6 | | S | Submarine – Coastal | Danziger Werft Danzig (Germany) | 10/5/1942 | 4/22/1943 | 8/4/1943 | Captured | |

| S 7 | | S | Submarine – Coastal | Schichau, Danzig (Germany) | 9/28/1942 | 3/30/1943 | 8/14/1943 | Captured | |

| S 8 | | S | Submarine – Coastal | Danziger Werft Danzig (Germany) | 10/27/1942 | | 8/25/1943 | Captured | |

| S 9 | | S | Submarine – Coastal | Schichau, Danzig (Germany) | 9/29/1942 | | 8/26/1943 | Captured | |

| Saetta | SA | Dardo 1a Serie | Destroyer | Cantieri del Tirreno (C.T.), Genova-Riva Trigoso | 5/27/1927 | 1/17/1932 | 5/10/1932 | Sunk | 2/3/1943 |

| Sagittario | SG | Spica tipo Perseo | Torpedo Boat | Cantieri Navali del Quarnaro (C.N.Q.), Fiume | 11/14/1935 | 6/21/1936 | 10/8/1936 | | |

| Salpa | SA | Argonauta | Submarine – Coastal | Tosi, Taranto | 4/23/1930 | 5/8/1932 | 12/12/1932 | Sunk | 6/27/1941 |

| San Giorgio | | San Giorgio | Obsolete Ship | Navalmeccanica, Castellammare | 7/4/1907 | 7/27/1908 | 7/1/1910 | Scuttled | |

| San Marco | | San Giorgio | Obsolete Ship | Navalmeccanica, Castellammare | | | | Captured | 9/9/1943 |

| San Martino | | Palestro | Destroyer | Orlando, Livorno | | | | | |

| Santarosa | SN | Bandiera | Submarine – Medium Range | Odero-Terni-Orlandi (O.T.O.), Muggiano (La Spezia) | 5/1/1928 | 10/22/1929 | 7/29/1930 | Scuttled | 1/20/1943 |

| Santorre Santarosa | SO | Settembrini | Submarine – Medium Range | Tosi, Taranto | 4/16/1928 | 3/29/1931 | 4/25/1932 | Removed from Service | 9/9/1943 |

| Scimitarra | C 33 | Gabbiano | Corvette | Breda, Venezia | 2/24/1942 | 9/16/1942 | 5/15/1943 | | |

| Scipione Africano | | Capitani Romani | Cruiser – Light | Odero-Terni-Orlandi (O.T.O.), Livorno | 9/28/1939 | 1/12/1941 | 4/23/1943 | Removed from Service | 8/9/1948 |

| Scirè | SR | Adua | Submarine – Coastal | Odero-Terni-Orlandi (O.T.O.), Muggiano (La Spezia) | 1/30/1937 | 1/6/1938 | 4/25/1938 | Sunk | 8/10/1942 |

| Scirocco | SC | Maestrale | Destroyer | Cantieri del Tirreno (C.T.), Genova-Riva Trigoso | 9/29/1931 | 4/22/1934 | 10/21/1934 | Wrecked | 3/23/1942 |

| Scure | C 62 | Gabbiano | Corvette | Breda, Venezia | 10/20/1943 | | | | |

| Sebenico | | Sebenico | Destroyer | Loires, Nantes (France) | | | | | |

| Serpente | AU | Argonauta | Submarine – Coastal | Tosi, Taranto | 4/23/1930 | 2/28/1932 | 11/12/1932 | Scuttled | 9/12/1943 |

| Settembrini | ST | Settembrini | Submarine – Medium Range | Tosi, Taranto | 4/16/1928 | 7/28/1930 | 1/25/1932 | Sunk | 9/9/1943 |

| Sfinge | C 47 | Gabbiano | Corvette | Cantieri Riuniti dell’Adriatico (C.R.D.A.), Monfalcone | 6/20/1942 | 9/1/1943 | 5/12/1943 | | |

| Sibilla | C 49 | Gabbiano | Corvette | Cantieri Riuniti dell’Adriatico (C.R.D.A.), Monfalcone | 6/20/1942 | 3/10/1943 | 6/5/1943 | | |

| Simone Schiaffino | | Rosolino Pilo | Destroyer | Odero-Terni-Orlandi (O.T.O.), Genova-Sestri Ponente | | | | | |

| Sirena | SI | Sirena | Submarine – Coastal | Cantieri Riuniti dell’Adriatico (C.R.D.A.), Monfalcone | 5/1/1931 | 1/26/1933 | 10/2/1933 | Scuttled | 9/9/1943 |