December 13th, 1941

The most authoritative book on the role of ULTRA in the Mediterranean conflict, “Il Vero Traditore” (The Real Traitor), written by Alberto Santoni, displays on its jacket the two light cruisers Da Barbiano and Di Giussano: this is not just a coincidence. After the tragic battle of Matapan, the night encounter of December 13th, 1941 was one of the worst disasters of the Italian Navy, and like the famous battle, it was brought about by the treacherous effect of technical superiority. But where at Matapan British intelligence was sketchy, in this case it was lethally accurate.

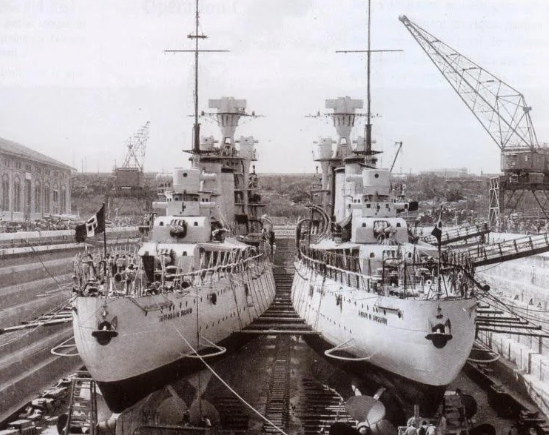

The R.N. Da Barbiano and R.N. Da Giussano in drydock around 1930

By the end of 1941, the situation in North Africa was near desperate. British forces were advancing under the impetuous operation “Crusader.” Fuel had almost been exhausted; Axis vehicles could not operate, airplanes assigned to the defense of Tripoli could not fly, and the whole war effort appeared near collapse. Once again, the Regia Marina was asked to deliver much needed supplies to the besieged colony.

December was a terrible month. With the arrival of force “B” in Malta by November 29, strengthened by the cruisers Ajax and Neptune and the destroyers Kimberly and Kingston, and under the command of Admiral Rawling, the Royal Navy had reasserted control over the Italian supply lines. After the successful arrival of the M\v Veniero, on December 1st, the ships following (Capo Faro, Adriatico, Mantovani) were all sunk with great loss of life and desperately needed supplies. It was then decided to use the battleship Duilio to provide for general coverage in the central Mediterranean, but as soon as the Italian Fleet left, British control was immediately reasserted.

Desperate situations call for desperate measures, and on December 4th, it was therefore decided to use military vessels to deliver supplies to Libya. The cruiser Cadorna was able to deliver personnel and fuel from Taranto to Benghazi on December 11th, two days before the Da Barbiano and Di Giussano had left Palermo for Tripoli. Meantime, the British were perfectly aware of the Italian mission which they were tracking via ULTRA.

After having been spotted by British aircraft, the commander of the formation, Admiral Toscano, ordered a return to port. With a large convoy scheduled to reach Libya on the 14th, the Regia Aeronautica was desperate for fuel. The two cruisers, again loaded with fuel stored on deck in large drums (100 tons of gasoline, 250 tons of diesel fuel, 600 tons of fuel oil, 900 tons of food and 135 military personnel), left port on the 12th. The cruiser Bande Nere, which was scheduled to participate, was left behind due to malfunctions, and the torpedo boat Cigno was sent instead.

Meantime, the destroyers Sikh, Legion, Maori and Isaac Sweers, this last one a Dutch vessel, under the command of Captain Stroke, left force “K” in Gibraltar to reinforce force “B” in Malta. The formation was reported by Italian Cant.Z.1007bis (1), but speed and direction gave Supermarina the erroneous sense that the two Italian cruisers would have enough margin of maneuver to avoid the British. Under the direction of ULTRA, the British formation increased speed and easily reached the Italian ships.

At 3.15 AM on December 13th, with the help of the Radar and completely undetected, the British ships maneuvered and launched an initial salvo of ten torpedoes. The Di Giussano was able to fire three shots before sinking, while the Da Barbiano was turned into a towering inferno, unable to return fire. The Cigno fought back, but to no avail. The British units left as quickly as they had come. The Cigno was able to rescue 500 sailors, while others reached the coast or were later saved by Italian M.A.S.. Over 900 men (2) lost their lives, including Admiral Toscano.

The only British mistake was reporting that the Bande Nere was present during the engagement, but this was probably due to the fact that the substitution of the Cigno for the disabled ship was not transmitted over radio dispatch and therefore it could not be intercepted.

(1) James J. Sadkovich “The Italian Navy in World War II”

(2) James J. Sadkovich reports 1225.

(3) Alberto Santoni, “Il Vero Traditore”