November 9th, 1941

The losses incurred by the Royal Navy in the Eastern Mediterranean during the evacuation of Greece and Crete in April and May, 1941 forced withdrawal of the Malta surface strike force. It was not reconstituted until October 21 when Force K, the light cruisers Aurora and Penelope and the destroyers Lance and Lively under the command of Captain Agnew arrived at Valetta’s Grand Harbor. As with Mack’s efforts in April, Agnew’s first two attempts to intercept Italian convoys on the nights of 25/26 October and 1 / 2 November failed. And like Mack, he succeeded on the third try, but even more spectacularly.

The Italians knew that surface ships had returned to Malta within a day of the event and fully appreciated the danger they represented. However, the tempo of the North African land war during the fall of 1941 dictated that more, not less supplies be shipped. Consequently an important convoy of seven ships, the German steamers Duisberg (7,389 tons) and San Marco (3,113 tons), the Italian motorships Maria (6,339 tons), and Rina Corrado (5,180 tons), the Italian steamer Sagitta (5,153 tons) and the Italian tankers Minatitlan (7,599 tons) and Conte di Misurata (5,014 tons) gathered at Naples. They were loaded with 13,290 tons of materiel, 1,579 tons of ammunition, 17,281 tons of fuel, 389 vehicles, 145 Italian troops and 78 Germans. Supermarina named the convoy Beta, and provided a generous escort. The direct escort consisted of destroyers Maestrale, flag of Captain Ugo Bisciani, Fulmine, Euro, Grecale, Libeccio and Oriani. The distant escort included heavy cruisers Trieste, flag of Rear-Admiral Bruno Brivonesi, and Trento with destroyers Granatiere, Fuciliere, Bersagliere and Alpino. The route took Beta east of Malta bound for Tripoli. Italian doctrine and experience dictated that the principal danger from the night portion of the passage would come from aircraft, that a surface interception was nearly impossible unless the convoy’s exact route and speed were known. Nor did the Italians appreciate the capabilities of radar.

The tanker Minatitlán on fire and sinking in the morning of 9 November 1941

The British learned of the convoy through Ultra intercepts of German Air Force transmissions (Webmaster note: Santoni denies this ever happening). A Maryland reconnaissance plane out of Malta “discovered” the convoy on the afternoon of the 8th. Force K sailed from Malta at 1730 and visually located the convoy about 135 miles east of Syracuse at 0039 on the 9th. The convoy was sailing at 9 knots in two columns about a half-mile apart. On the starboard side the order was Duisberg, San Marco and Conte de Misurata. On the port Minatitlan led Maria and Sagitta while Rinacorrada brought up the rear between the two columns. The distant escort followed about three miles astern, off the convoy’s starboard quarter, sailing at 12 knots. Maestrule sailed at the head of the convoy while Fulmine, and Euro guarded the starboard side, Libeccio and Oriani the port side and Grecale, followed up the rear. Force K was in line-ahead with Aurora leading followed by Lance, Penelope and Lively. After Aurora’s sighting, Agnew maneuvered to a position down-moon of the Italians, putting his ships on the convoy’s starboard quarter. During this evolution, the direct escort sighted the British, but mistook them for the friendly cruiser group.

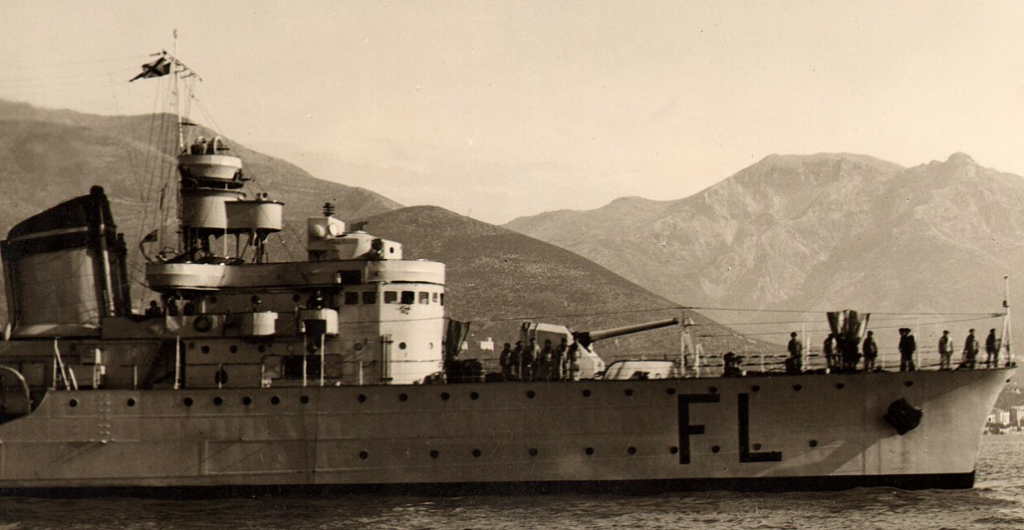

R.N. Fulmine

Once in position, Force K laid guns with radar and opened fire at 0057 from 3,300 to 5,500 yards. The bright moonlight silhouetted the Italian ships adding to the tactical and technological advantages the British already enjoyed. Aurora targeted Grecale and scored hits with her first three salvos, setting off an explosion, starting a fire and leaving her dead in the water. Penelope’s initial salvos hit Maestrale. Lance took on one of the cargo ships and, after obtaining hits from 4,000 yards, shifted fire to Fulmine. Lively was the last to open fire at 0100. She hit Duisberg with her first salvo and followed with five more before shifting her guns to Euro. These initial salvos were deadly and indeed the whole action was characterized by extremely accurate shooting by the British.

Aurora then fired on Maestrale. She was making smoke and withdrawing around the front of the convoy to its port side. She ordered Libeccio and Oriani also on the port, the unengaged side, to make smoke. Bisciani then ordered the escorts to gather around him. This order and the destroyer’s movements supports the suggestion that he believed the attack was coming from the port, not the starboard, side and that he continued to mistake the ships of Force K for Trieste and Trento. In any case, after issuing these instructions, Bisciani lost his ability to influence the battle further when Aurora shot Maestrale’s radio antenna away.

Euro and Fulmine on the right of the convoy had a better appreciation of the situation. They counterattacked the British, but Fulmine was quickly hit hard and repeatedly by Lance and then Penelope. She returned fire only briefly before she turned over and sank at 0106, just nine minutes into the action. Euro, commanded by Cigala Fulgosi, who successfully defended the second Cretan Convoy with Sagittario, approached to within 2,100 yards of the British without suffering damage. He had a perfect torpedo setup and was about to launch when Maestrale’s orders made him wonder if he was attacking his own cruisers. He turned away, but realized his mistake when first Lively and then Aurora and Penelope brought him under fire. Euro was hit six times, but the 6″ shells passed through her thin hull without causing major damage.

The Italian distant escort was about 5,500 yards from the convoy’s right side (the Malta side) when the action opened. They came up increasing speed to 24 knots as the British sailed away and then circled around the head of the convoy and down it’s opposite side at 20 knots. The Italian cruisers were not slow in engaging the British, opening fire at 0103 from 7,800 yards, but their position was bad and quickly became worse. In effect, the British unintentionally kept the convoy between them and the heavy cruisers. Trieste and Trento shot off 207 rounds of 8″ and 82 rounds of 3.9″ ammunition, but by 0125, they ceased fire, reporting the British were out of range. The British assumed these vessels were more destroyers and Aurora returned fire with her 4″ guns, but the range was too great for these to be effective.

The convoy ships, meanwhile, believed they were under aerial attack and took no evasive action throughout. From 0110 Agnew proceeded to circle around the head of the convoy and then up its port side, at ranges down to 2,000 yards, picking off merchant ships with gunfire and torpedoes. The British were rather astounded at the way the cargo ships continued serenely on course, almost waiting their turn to be sunk. Libeccio and Oriani with Maestrale and Euro of the direct escort withdrew about ten miles to the east of the convoy and regrouped. They then counter-attacked as a unit, firing salvos, but declining to use torpedoes for fear of hitting their own ships beyond the British. It is interesting to compare this reticence with the Japanese action at the Battle of Sunda Strait. The Japanese didn’t hesitate to fill the waters with torpedoes to get at Allied warships attacking transports, sinking four of their own transports as a consequence. The four destroyers led by Maestrale continued to make smoke and periodically engaged as they came in view, but they failed to seriously challenge the British and suffered only slight damage to Libeccio as a result. Meanwhile the distant escort continued sailing down the convoy’s starboard in the opposition direction.

In effect, the Italian heavy cruisers and Force K switched places, the first ending up south and west of the convoy by the time the British were north and east. Agnew ordered cease-fire at 0140 as the British passed by the rear of the now destroyed convoy. No new targets were seen, and concerned with the shortages of 6″ ammunition at Malta, (Penelope, for example, shot off 259 6″ rounds) the British shaped course for home at 0205. They sank every one of the cargo ships and tankers and sank one destroyer and damaged three others. Although on several occasions the British reported they avoided torpedoes, Italian accounts deny that any of their destroyers used this weapon. The only injury suffered by the British was splinter damage to Lively. A star shell burst overhead and near misses holed her funnel and a steam pipe on the starboard siren. To add to the Italian’s misery, the British submarine Upholder torpedoed Libeccio the next day at 1048 while she was engaged in rescue work. Euro tried to tow the stricken ship to safety, but Libeccio broke apart and sank shortly after.

This battle was one of the most complete victories won by the British during the war. They were out numbered and outgunned by the escort, but application of superior doctrine and technology along with luck and surprise gave them the victory. Both Brivonesi and Bisciani were relieved, although Brivonesi was subsequently returned to command.

Reference: 08/09 Nov 41.R&H 97, B 132-133, Ireland 103, Grove 57-59, Smith/Walker 46, Bekker 238-240, S196-197. Greene196-196

Text copyright Vince O’Hara, 2000