Start Here

About us

REGIAMARINA ™ started in 1996 here in the United States as a small site dedicated to the Heavy Cruiser Gorizia, the only survivor of its class to the disaster of Matapan. Over the years, as Web technology evolved and became more complex, we have always strived to favor content over presentation. Still, after so many years of adding new sections and material, and having reached over 1,300 Web pages and thousands of daily visitors, we decided to make radical changes to the Web site.

Many years ago, to favor the fast deployment of new content without having to code Web pages, we implement a Swiss CMS (Content Management System) which allowed us to release new content – we used to publish in both English and Italian – somewhat more easily than coding HTML pages. However, we have now switched to WordPress and have opted to only publish in English. Eventually, in the future, we will also try to republish all the material in Italian.

Since every single page of the old site has been replaced, bookmarked pages or pages referred to in outside links will no longer work. If you cannot find what you were looking for, please use the advance search function or the site index.

As we continue gathering new material, we hope you may find this site of use to you.

REGIAMARINA ™

A Brief Analysis

of the Italian Navy during World War II

In the Mediterranean, the situation of military power, in terms of quantity, appeared to be balanced. The Italian Fleet, of some importance for the number of surface and submarine forces, could have withstood the heavy weight of the opposing French and English forces.

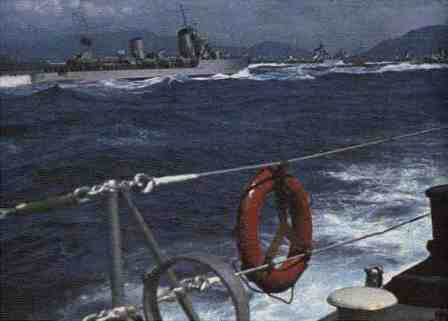

July 9th, 1940. Cruisers of the 2nd Squadron on route to Calabria.

(Photo USMM).

After Italy’s entry into the war, June 10 1940, this apparently balanced situation was gradually compromised by several factors, including: The stronger British power in naval aviation. Italian lack of instruments of detection (radar) and fuel. British ability to easily resort to naval and industrial power from other sectors of operation to replace losses in the Mediterranean.

Despite these adversities, the Italian Navy, in more than three years of hard engagement, was able to reach the peace table with all of its battleships. Italian naval forces fought on all seas. The men from the special forces, submariners, naval aviators, crew from small and large ships and marines from the regiment San Marco, clearly distinguished themselves for their perseverance and valor in obeying the law which states that “when the Motherland is at war, everyone must obey up to the ultimate sacrifice”.

Between 1940 and 1943, along with the Merchant Marine, the Italian Navy , despite the bitter opposition from British naval and aerial forces, was able to deliver to North Africa 86% of all war material and 92% of all troops shipped.

Some data eloquently summarizes the Italian effort in the war at sea: 3 million hours of operations for a total of 37 million miles sailed, equal to 2000 trips around the equator. 126,000 hours of aerial observation with 31,107 missions.

The naval routes with Albania, Greece and North Africa were always operational, averaging four concurrent convoys at sea. Transportation between the areas of operation was never interrupted. Such a result must be considered admirable especially considering the limited forces in place and the presence and location of the British military base of Malta. British traff on the prescribed routes toward Africa could have easily been considered an absurdity.

Nevertheless, the Mercantile Navy completed its assignment at the incredibly high price of 2,513 ships sunk between June 10,1940 and September 8, 1943.

The “Medaglia d’Oro al Valor Militare” awarded to the flag of the Italian Navy, to the Special Forces, the cruiser San Giorgio, and the submarine Scire along with 158 “Medaglie d’Oro al Valore” and the 4 “al Valore di Marina”, clearly represent the highest possible measurement of the sacrifice and the devotion to the Motherland shown by the Italian Navy between 1940 and 1945.

Introduction

On May 5th, 1938 the Regia Marina, the Royal Italian Navy, was paraded in the Gulf of Naples for the benefit of the visiting German chancellor Adolf Hitler. Although the German military staff had advised the German Chancellor on the inadequacy of the Italian Navy and the general lack of readiness of the whole Italian defense force, the fuehrer was impressed by the great spectacle.

The high marksmanship demonstrated by the Italian gunnery and the impressive coordination of dozens of Italian submarines diving and reemerging in perfect synchrony was the disguising prelude to the fierce naval battles, which ultimately, in less than three years, would almost obliterate the 5th naval power in the world.

Italian destroyers in the Gulf of Naples

After the naval agreements signed in Washington, also known as the “Naval Holiday”, Italy rebuilt several battleships and constructed new, powerful, heavy cruisers and many lesser ships. What the Italian Navy did not have, and would gravely pay for during the conflict, were aircraft carriers, enough supplies of oil, spare parts and, most of all, trained officers and crew.

The performance of the Italian Navy between June 10th, 1940 and September 8th 1943 can be summarized by its tremendous losses: 28,937 casualties, 13 cruisers, 42 destroyers, 41 minelayers, 3 corvettes, 84 submarines and many more lesser ships. To increase these losses, after the Italian capitulation, the Regia Marina lost 2 battleships, 4 cruisers, 11 destroyers, 30 submarines and many more lesser ships.

At the same time, despite the high losses, Italian officers and crew belonging to the 10th Light Flotilla wrote the most heroic pages of sea warfare in World War II. The 10th Light Flotilla alone sank 28 ships, including the battleships Queen Elisabeth and Valiant and the cruiser York. Ultimately, by keeping the flow of supplies between the mainland and North Africa, the Regia Marina accomplished its mission. These Web pages are dedicated to the memory of those who fought, in both camps, during this tragic period of modern history. Their unmarked graves are a solemn monument to their valor.