Forewords

The Battle of the Atlantic describes the prolonged struggles between the British Empire, and later American forces, for the maintenance of supply routes to and from Great Britain and its possessions. On reverse, the Italians fought a similar battle in the Mediterranean where they found themselves on the other side, having to defend their freighters and tankers from British attacks. This epic, involving thousands of ships and submarines, started as early as 1939 and ended in early 1945. Many historians have divided this battle into distinct phases. The author Clay Blair, in his two-volume, 1,800-page book “Hitler’s U-Boat War”, defines two major phases: “The Hunters ”, from 1939 to 1942, and “The Hunted ”, from 1942 to the end of the conflict in 1945. Grand Admiral Karl Doenitz, the head of the German submarine forces during this struggle, and author of “Memoirs, ten years and twenty days”, uses a more detailed timeline in which the struggle between tactics, technology, and strategies becomes clearer.

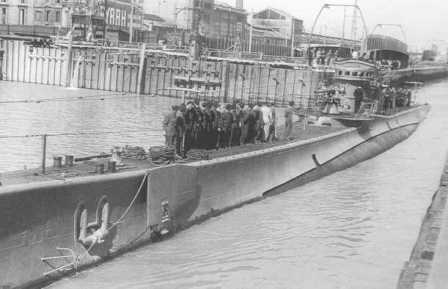

R. Smg Torelli and R. Smg Faa di Bruno upon their arrival in Bordeaux

A copious bibliography, both works of authors who directly participated in the conflict and those who just made a career studying it, has created much information, but at the same time blurred some of the historical accuracy. In this cacophony of voices, often as loud and erroneous as Clay Blair, the work of Jurgen Rohwer remains one of the foundations for accurate historical research. He is, amongst some American and Italian historians, one of the few who has cited the Italian participation, this lesser know, but important aspect of the Battle of the Atlantic.

R. Smg. Da Vinci

The predominant role of the German U-Boats is unquestionable. Still, at the end of summer 1940, when the number of operational U-Boats in the Atlantic was getting close to single digits, the arrival of the larger, slower, and less maneuverable Italian submarine boosted German confidence and allowed for the construction of new boats and the formation of new crews. While the Italians had started the conflict with older, but more experienced officers, not fully capable of withstanding the hardship of long patrols in the confinement of these relatively small boats, Germans had a large number of young and highly motivated officers. Eventually, younger Italian officers, having acquired the necessary experience under more senior officers, led the few remaining Italian boats to excellent success, while the hundreds of new German U-Boats had to be manned with less experienced officers and crew, causing a staggering number of losses especially during their maiden patrols.

Considering that Italy entered the battle almost a year after the Germans, and exited in 1943 following the Italian capitulation, the analysis of military operations will focus mostly on this period. In essence, the Italian submarine forces experienced several distinct phases:

The transfer from the Mediterranean to the Atlantic (from June to December 1940)

The early wolf-pack operations (from October to December 1940)

The collaboration with the German forces (from October 1940 to May 1941)

The cessation of joint operations and the transfer of operations from the northern to the central Atlantic (from December 1940 to January 1942)

Operations along the American coast (from February to August 1942)

Operations in the southern Atlantic (from September 1942 to May 1943)

The re-purposing of the remaining Italian submarines for transport missions to Japan (from mid 1943 onward); and some special operations.

Italian Submarines in the Atlantic

Despite having built a sizable fleet of oceanic submariners, the Italian command had failed to properly analyze the implications surrounding the crossing of the Strait of Gibraltar, a narrow at the western end of the Mediterranean heavily guarded by the British Navy. The first three submarines sent to the Atlantic, the Malaspina , Barbarigo and Dandolo , crossed the strait in August 1940 without incident, sank a total of 13,593 tons, and since the submarine base of Betasom had just become operative, instead of returning to Italy, were rerouted to Bordeaux. In the subsequent weeks, a total of 27 Italian submarines crossed the strait with only one unit, the Bianchi, being damaged by a British patrol . Before reaching Bordeaux, these submarines were deployed west of the Strait of Gibraltar, achieving some negligible results. It was indicative that the first group sent to the Atlantic included also the Tazzoli , Cappellini , and Glauco, but none of these boats was even able to reach the Strait of Gibraltar due to technical failures. Failures would plague Italian submarines throughout the conflict, but while diesel engines, pumps, and other equipment often failed, weaponry (deck guns and torpedoes) was in general quite reliable.

Soon after, a new group of submarines including the Emo, Faà di Bruno, Giuliani, Tarantini, Torelli, and Baracca left Italian bases for the Atlantic. A third group, including the Marconi, Finzi and Bagnolini, left in early September, a fourth group including the Da Vinci and Otaria crossed the Strait of Gibraltar at the end of September, and a fifth group including the Glauco, Veniero, Nani, Cappellini, Calvi, Tazzoli, and the Argo the following new moon. To avoid detection, after the very first Italian submarine had crossed on the surface and reported on the experience, it was decided to proceed submerged and during a period of new moon. Of the new submariners, the Cappellini, would become the protagonist of an unusual event. After having sunk the freighter Kabalo , the captain would rescue the crew in an epic rescue operation , but the fight during the Battle of the Atlantic would not have room for chivalries.

On September 30th, Dönitz visited Bordeaux to arrange joint military operations . Because Hitler did not want to have German forces soon to be deployed in North Africa under Italian command, the Italian submarines in Bordeaux were officially left under Italian command. Practically, Dönitz intended to have full control of these precious submarines, and the Italian commanding officer, Rear-Admiral Parona , was ready to oblige. Fluent in German, Parona had previously translated some German military literature in the area of submarine tactics, and was a highly respected submariner.

Collaboration with the Germans and Early Successes

In early October the first four Italian submarines left Bordeaux to participate in a joint operation with the U-Boats. The Malspina, Dandolo, Otaria and Barbarigo joined 11 German submarines in an operation against several British convoys. Other patrols involving more Italian submarines took place until early December. In all, 42 German U-Boats and 8 Italian “sommergibili” sank 74 ships. Unfortunately, the 310,565 tons sunk by the Germans dwarf the 25,600 tons sunk by the Italians. Thus, early German excitement waned and some recrimination surfaced, despite the Italians having lost two submarines, the Faà di Bruno and Tarantini, with all hands on board.

Soon after, the Germans informed the Italians that joint operations would be reconsidered. Fault was not, and could not be fully placed on the shoulders of the inexperienced Italian captains. In most cases, failure to properly communicate was caused by the German High Command’s unwillingness to place German communication personnel aboard the Italian boats. Thus, after a sighting, an Italian boat would have to inform Bordeaux and this base would later inform Paris . At best, the delay amounted to an hour, unless the Teletype line between the two commands was down. Furthermore, it was recognized that the Italian submarines were ill equipped for the harsh conditions of the north Atlantic. The engines did not have an air intake built into the conning tower, thus the turret hatch had to be left open, causing water to often rush into the hull. Italian boats were also slower than their German counterpart, larger in size, easier to detect and lacking “aiming angle calculators” to properly adjust the launch of torpedoes. Most of these shortcomings were remedied, with the assistance of the Germans , by altering the structure of the boat. The work of Rear-Admiral (E) Fenu, supported by Commander Hans Rösing and later Commander Franz Becker, allowed for the Italian submarines to acquire some greater level of efficiency. It was, under all aspects, a Herculean task. Still, in terms of supplies, including diesel fuel, all equipment, ordinance, and provisioning was shipped from Italy via train.

Although Italian captains in general were not allowed to train aboard German submarines, Commander Primo Longobardo was permitted to complete a patrol aboard Otto Kretschmer’s U 99. The experience acquired during this patrol allowed Longobardo, as captain of the Torelli, to sink four ships for a total of 17,409 tons in a single patrol . Nevertheless, the performance of the Italian forces was considered marginal, and some vessels were rerouted to the central Atlantic where climatic conditions were considered better suited for crews and vessels. In this crucial period, the Germans were left with only 16 U-Boats; 4 operating in the north Atlantic, 2 returning to base, and 10 in Lorient refitting.

Second Attempt of Collaboration with the German Forces

January 1941 was the low point of German activity in the Atlantic. As said, there were only 16 U-Boats. This forced Dönitz to reconsider joint operations with the Italians, despite earlier failures. After initial alterations made to some of the Italian submarines, the Germans considered a second attempt at joint operations. Between February 19th and March 23rd, 1941 a total of 47 U-Boats and 16 “sommergibili” attacked 9 British convoys. The Germans lost 4 U-Boats, the Italians lost the Marcello . Once again, the 154,743 tons sunk by the Germans were not matched by the Italians who only sank 12,292 tons. All three ships sunk by the Italians were units dispersed from a convoy. Thus, it was realized that, amongst many other reasons, the speed and displacement of the Italian submarines made them more suitable for independent operations rather that “wolf pack ” attacks. March 1941 would be a terrible month for the German forces. After the loss of Gunther Prien’s U 47 , the two high scoring captains Kretschtner and Schepke were also lost. The confidence of the Germans was shaken, and at the same time the Italians failed to provide for much support, barring Cappellini’s assistance offered to U 97 during the chase of the boarding vessels Camito and Sangro.

End of Joint Operations

With the arrival of new boats and crews from Germany, Admiral Dönitz was ready to cease joint operations with the Italians. Meantime, the increased successes obtained by the British were not coincidental. In February 1941, Admiral Sir Percy Noble was made Commander in Chief of the Western Approaches and he moved his headquarters to Liverpool. He reorganized the defenses, setting up a tracking room, and began integrating “Liberators”, large four-engine bombers, which Great Britain was receiving from the United States, into the coastal defenses. Fifty old destroyers were also acquired from the United States under a controversial deal orchestrated by President Roosevelt, and fitted with new antisubmarine weapons and tracking devices.

On May 14th, Admiral Parona met again with Dönitz and it was agreed that joint operations would be suspended and the Italian boats would move their patrol area west of the Strait of Gibraltar and possibly off Freetown. Meantime, the submarine Giuliani was transferred to Gotenhafen , on the Baltic, at the German submarine school where Italian officers and crews were trained on attack techniques and methodologies employed by the Germans .

The experience acquired training with the Germans was very valuable and demonstrated that, if collaboration had started earlier, it could have produced much better results. Thus, in May Italian boats began patrolling the central Atlantic and successes began crowning these long patrols. Operations continued until September with the Marconi, Da Vinci, Morosini, Malaspina, Torelli, Barbarigo all achieving results. Italian successes came at a price; the Baracca and the Malaspina were lost, followed in October by the Marconi . On October 25th, the Ferraris was scuttles after aerial bombing followed by an attack by the British destroyer H.M.S. Lamerton east of the Azores Islands.

Special Operations and Patrols of Freetown

On September 30th, 1940 Dönitz and Parona discussed the possibility of sending the larger Italian submarines in the area around Freetown. These patrols did not take place until March 1941, and two of the boats returned empty handed, while Captain Fecia di Cossato of the Tazzoli sank several ships. Meantime, Italian East Africa was rapidly falling and the remaining operational submarines still in the area were sent to Bordeaux. During the long voyage, the Guglielmotti, Archimede and Ferraris navigated without stopping, refueling at sea only once, while the small Perla, a coastal submarine, refueled twice. The mission took 64 days for the larger boats, and 80 for the smaller Perla and should be considered a great nautical achievement for the Italian captains and a sign that collaboration with the Germans was still good, since they provided for open sea refueling.

Another special operation took place in late 1941 following the sinking of the German raider Atlantis. Intercepted by the British cruiser Devonshire, after the position of the German ship had been detected by “Enigma”, the crew was rescued by the supply ship Python, which was later intercepted and sunk by the cruiser Dorsetshire. Two German submarines took aboard 414 survivors and Dönitz immediately requested assistance from the Italians. The capacious Torelli, Tazzoli, Calvi and Finzi were sent full speed ahead south to meet the German U-Boats and picked up 254 survivors. The four boats reached the French port of Saint-Nazaire around Christmas day, completing one of the most spectacular rescue operations of the war and at the same time earning the German’s deepest gratitude.

Crisis in the Mediterranean

Italy’s adventurous entry into the war along with the Germans began having its catastrophic effects and, in early 1941 , the situation in the Mediterranean was nearly desperate. The Italian High Command, following the personal intervention of Benito Mussolini, informed the Germans that the base in Bordeaux would be closed and all boats would return to Italy. Discussion took place at a very high level and eventually Dönitz was able to convince the Italians to maintain their base and only return a smaller number of submarines to the Mediterranean. The transfer took place between June and October 1941, and one after another the Argo, Brin, Dandolo, Emo, Guglielmotti, Torelli, Mocenigo, Otaria, Perla, Velella and Veniero were sent back while the Glauco was lost en route. Meantime, six German U-boats were transferred to the Mediterranean where they would achieve remarkable successes, including the sinking of a battleship and an aircraft carrier.

Operations Along the American Coast

After the bombing of Pearl Harbor on December 7th, 1941 and the subsequent declaration of war by Germany and Italy on the United States, the U-Boats began “Operation Paukenschlag”, commencing unrestricted submarine warfare along the East Coast of the United States. As early as January 1942, the Da Vinci, Torelli, Morosini and Finzi were sent to the Antilles, followed in March by the Calvi. As both Captain Mario Rossetto and Rohwer Jurgen documented, during this period the results obtained by the Italian submarines were equal to those of the German U-Boats. The gap had been closed, but while Germany was producing a new U-Boat each day, Italy’s production was very limited and focused on the smaller coastal boats operating in the Mediterranean. Once again, since the Italian boats had greater endurance than their German counterparts and Dönitz did not have enough of the new long-range type IX U-Boats, the Italians were asked to patrol off the Brazilian coast. Starting in April and through May, the Cappellini, Barbarigo, Bagnolini, Archimede and Da Vinci departed Bordeaux for the long voyage to Brazil. There were good successes, despite the fact that the American Navy had begun setting up better escorts and extended aerial reconnaissance.

On the 19th of May, the Captain of the Barbarigo, Enzo Grossi , informed Betasom of the sinking of an American battleship, possibly a Maryland or a California. Soon after, despite some concerns already raised in Bordeaux, “Comando Supremo ” published the news in an official war bulletin; the Americans promptly rebutted it. It is said that Mussolini himself, a journalist by profession, edited the announcement himself. This would be the first of two fictitious battleship sinkings claimed by Commander Grossi. These episodes contributed to discrediting the reputation of the Italian submarine force. A second group of submarines was sent to Brazil, which included the Torelli, Morosini, Giuliani and Tazzoli. Despite the increased escort, they sank several ships, but on the way back to France the Morosini was lost, probably to a mine just off Bordeaux. On September 15th, the Calvi was scuttled after an attack by the British destroyer H.M.S. Lulworth near the Azores.

Operations off Freetown and the South Atlantic

While the operations off the Americas were taking place, Betasom organized a few patrols off Freetown and later into the South Atlantic. The Cappellini, following the sinking of the liner Laconia by U 156, intervened to rescue some of the thousands of POW’s rescued by the U-boat. The sinking of the Laconia was a sad and regrettable event and one of the darkest pages of World War Two. Meantime, the Archimede, under the command of Lieutenant Commander Saccardo, sank the large transport Oronsay and nearly missed the equally large Nea Hellas. On the 6th of October, the already mentioned Grossi claimed another imaginary battleship, this time a Mississippi-class one. He was awarded the German Knights Cross and the Italian Gold Medal, rewards he later had to return. In October, the Italians were once again off the Brazilian coast. This time the Da Vinci, and Tazzoli scored well, while the Finzi returned empty handed. A fourth boat, the submarine cruiser Cagni, was sent all the way to Cape Town, but after a record-long mission of 137 days at sea, it only had 5,840 tons to its credit .

Another group of six submarines followed. The Barbarigo, now under new command, sank three ships for a total of 15,584 tons; the Da Vinci sank six ships for a record 58,973 tons , including the large liner Empress of Canada. These were stunning results only exceeded by Lieutenant Commander Henke of U 513 . The Finzi also sank ships, but the successes of the Italian submarine fleet came at a very high price. The Archimede was sunk by an American plane near the island of Fernando di Noronha, off the Brazilian coast, and the Da Vinci did not return to base, probably sunk on May 23rd, 1943 by the frigates Active and Ness 300 miles off Vigo, Spain. Two more vessels, the Torelli and the Bagnolini, returned without successes. After three years of continuous operations, the few remaining boats were worn out and no longer deemed fit for war patrol.

Transport Missions to Japan

On February 8th, 1943 Dönitz proposed to the Italians to re-purpose the remaining submarine for transport service from France to Japan. In exchange, the Germans would transfer 10 VII-C class U-boats to the Italian Navy and Italian crews and commanders began training in Germany soon after. Under the supervision of Rear-Admiral (E) Fenu, the remaining boats began extensive refitting work. The deck guns were removed, the ammunition magazines turned into additional fuel depots, the attack periscope removed, and a great part of the on board comforts, including one of the heads, removed to give space to cargo. The torpedo tubes were also sheared off. With the transformation of these few remaining boats, the Italian participation to the Battle of the Atlantic practically concluded. The sacrifice had been great; the result achieved would fuel a lasting debate, which is still ongoing. Of the 10 submarines assigned to transport missions to Japan, only seven were still in service when the transformation began .

Before the Italian armistice of September 8th, 1943 only the Cappellini, Torelli and Giuliani left port and, after a long and perilous voyage, reached Singapore. Here the boats were captured by the Japanese and transferred to the German Navy. Of the boats, the story of the Cappellini is probably the most amazing. On September 8th, (actually the morning of the 9th), having received news of the armistice signed by the Italian government, the Japanese immediately took control of the boat. The crew was captured and interned in a Japanese P.O.W. camp. Later on, a good part of the crew (not the officers) decided to continue fighting along side the Germans, and the submarine was manned by a mixed crew of German and Italian sailors. Incorporated in the Kriegsmarine, the boat was assigned the nominative UIT.24. At the surrender of Germany, May 10th 1945, the boat was incorporated into the Japanese navy with the nominative I-503 where it continued to operate until the end of the conflict with a mixed Italian, German, Japanese crew. The Cappellini, was eventually captured by the United States and sunk in the deep waters off Kobe on April 16th, 1946.

Conclutions

Betasom would remain fully operational until September 8th, 1943 when, after the Italian armistice, it was occupied by the Germans. Thereafter, some Italian personnel opted to continue fighting alongside the Germans, but Italian command was never re-established. The type VII submarines assigned to Italy were quickly reposed by the Kriesgmarine, and the few Italian submarines left in Bordeaux were too worn out for any possible use. It should be noted that while the Germans built concrete pens for their boats in Bordeaux, the Italian submarines where always exposed to aerial attacks. Despite this weakness, not a single vessel was lost in port or along the Gironde to aerial attacks. Thus, although restricted in the number of submarines deployed and the total tonnage sunk, the Italian contribution to the Battle of the Atlantic should be insignificant. On the contrary, in the perspective of the mammoth struggle which eventually saw British ingenuity and American industrial might prevail over the Axis, we should recognize that despite having fought for an unjust cause, the Italian submariners in the Atlantic contributed to writing one of the most epic pages of naval warfare.