| Rank (Equivalents) | Name | Assignment (Italian) | Assignment (English) | Started | Ended |

| Ammiraglio di Divisione | Parona, Angelo | Comandante Superiore | Commanding Officer | 8/31/1940 | 4/8/1941 |

| Contrammiraglio di Divisione | Parona, Angelo | = | = | 4/9/1941 | 9/17/1941 |

| Capitano di Vascello | Polacchini, Romolo | = | = | 9/18/1941 | 9/4/1942 |

| Contrammiraglio | Polacchini, Romolo | = | = | 9/5/1942 | 12/28/1942 |

| Capitano di Vascello | Grossi, Enzo | = | = | 12/29/1942 | 9/8/1943 |

| Capitano di Fregata | Cocchia, Aldo | Capo di Stato Maggiore | Chief of Staff | 10/7/1940 | 11/7/1940 |

| Capitano di Vascello | Cocchia, Aldo | = | = | 11/8/1940 | 4/24/1941 |

| Capitano di Vascello | Polacchini, Romolo | = | = | 4/25/1941 | 9/17/1941 |

| Capitano di Fregata | Caridi, Giuseppe | = | = | 10/1/1941 | 3/1/1943 |

| Capitano di Fregata | Corsi, Ferdinando | Coadiutore del Comandante | Adjutant to the Commanding officer | 1/22/1943 | 9/8/1943 |

| Capitano di Fregata | Capone, Teodorico | Comandante della Base | Base Commander | 8/25/1940 | 2/22/1942 |

| Capitano di Fregata | Caridi, Giuseppe | = | = | 2/23/1942 | 3/1/1943 |

| Capitano di Corvetta | De Giacomo, Antonio | = | = | 6/1/1943 | 9/8/1943 |

| Capitano di Corvetta | de Moratti, Bruno | Capo Servizio Comunicazioni | Chief Communication Officer | 9/1/1940 | 4/28/1941 |

| Capitano di Corvetta | Alesi, Massimo | = | = | 4/29/1941 | 9/15/1941 |

| Capitano di Corvetta | De Giacomo, Antonio | = | = | 6/1/1943 | 9/8/1943 |

| Capitano di Corvetta | Giudice, Ugo | Capo Servizio Operazioni | Chief Operations Officer | 8/31/1940 | 2/8/1941 |

| Capitano di Corvetta | Anfossi, Giovenale | = | = | 4/15/1941 | 2/10/1943 |

| Tenente di Vascello | Auconi, Walter | Capo Servizio Armi | Chief Armament Officer | 9/8/1940 | 4/14/1941 |

| Capitano di Corvetta | Lesca, Riccardo | = | = | 4/15/1941 | 1/26/1942 |

| Tenente di Vascello | Coletto, Giacomo | Comandante Compagnia Battaglione ” San Marco” | Commander “San Marco” Battalion | 3/12/194 | 12/6/1942 |

| Maggiore Genio Navale | Fenu, Giullo | Capo Servizio Genio Navale | Chief Naval Engineer | 8/31/1940 | 9/8/1943 |

| Maggiore Medico | Crucilla, Giulio | Capo Servizio Sanitario | Chief Medical Officer | 8/25/1940 | 3/1/1941 |

| Maggiore Medico | Meoni, Mario | = | = | 3/2/1941 | 8/5/1942 |

| Maggiore Medico | Castellani, Giuseppe | = | = | 8/6/1942 | 9/8/1943 |

| Tenente Colonnello Commissario | Di Losa, Mario | Capo Servizio Amministrativo | Chief Administrative Officer | 8/31/1940 | 4/24/1941 |

| Maggiore Commissario | Villani, Guido | = | = | 4/25/1941 | 6/20/1942 |

| Maggiore Commissario | Achilli, Pietro | = | = | 6/21/19429/8/1943 | |

| Tenente Colonnello di Porto | Benifei, Mario | Requisizioni Navi | Ship Requisitions | 4/30/1941 | 5/15/1943 |

| Tenente Colonnello di Porto | De Renzi, Ettore | = | = | 2/20/1943 | 9/8/1943 |

| Tenente Colonnello di Porto | Camino, Michele | = | = | 4/17/1942 | 2/15/1943 |

| Maggiore di Porto | Scaparro, Giovanni | = | = | 4/11/1941 | 12/31/1941 |

| Tenente Colonnello di Porto | Scaparro, Giovanni | = | = | 1/1/1942 | 5/12/1942 |

| Tenente Cappellano | Messori Roncaglia, Cario | Assistenza spirituale | Chaplan | 11/29/1940 | 9/8/1943 |

| Maggiore Granatieri | Orgera, Franco | Comandante Reparti Battaglione “San Marco” | Commander Group “San Marco” | 9/20/1940 | 3/20/1941 |

| Capitano Granatieri | Gatti, Giovanni | = | = | 3/21/1941 | 8/19/1943 |

| Tenente Carabinieri | Sottiletti, Roberto | Comandante 282* Sezione Carabinieri Mobilitata | Commander, 282nd Carabinieri | 4/29/1941 | 2/21/1942 |

| Tenente Carabinieri | Ippolito, Michele | = | = | 2/22/1942 | 9/8/1943 |

Bordeaux

Italian Submarines Assigned to BETASOM

The following is a list of all the Italian submarines that were assigned to the naval base of Bordeaux codename BETASOM. Boats with a departure date indicate that they returned to Italy. Boat with a lost date indicate that they were lost while serving as part of the BETASOM base.

| Boat | Arrival | Departure | Lost | Notes | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Alessandro Malaspina | 9/4/1940 | 9/11/1941 | Sunk by depth charges from Sunderland “U” (serial # W3986) of 10 Squadron RAAF, piloted by Flight Lieutenant Athol Galway Hope Wearne, in position 46º23’N / 11º22’W.” | ||

| Alpino Bagnolini | 9/30/1940 | 3/12/1943 | Captured by the Germans in Bordeaux, later sunk by British airplanes while in transit to Japan off Cape Good Hope | ||

| Ammiraglio Cagni | 2/20/1943 | 8/8/1943 | Surrendered to the Allies in Durban, South Africa September 1943 | ||

| Archimede | 5/7/1941 | 4/15/1943 | Sunk by an American plane (VP No 83 Squadron) near the island of Fernando di Noronha, off the Brazilian coast. | ||

| Argo | 10/24/1940 | 10/20/1941 | |||

| Barbarigo | 9/8/1940 | 6/16/1943 | Lost between the 16th and the 24th in the Bay of Biscay | ||

| Brin | 12/18/1940 | 8/28/1941 | |||

| Capitano Tarantini | 10/5/1940 | 12/15/1940 | Torpedoed by the British submarine H.M. S/MThunderbolt at the estuary of the river Girond (Atlantic) | ||

| Comandante Cappellini | 11/5/1940 | 9/8/1943 | Captured by the Japanese in Sapang | ||

| Comandante Faa di Bruno | 10/5/1940 | 10/31/1940 | Sunk in Atlantic between 10/31 and 1/5/1941. The British Admiralty claimes that it was sunk by H.M.S. Havelock on Nov. 8th, 1940. | ||

| Dandolo | 9/10/1940 | 7/2/1941 | |||

| Emo | 10/3/1940 | 8/27/1941 | |||

| Enrico Tazzoli | 10/24/1940 | 5/18/1943 | Sunk between the 18 and the 24 in the Bay of Biscay | ||

| Ferraris | 5/9/1941 | 10/25/1941 | Scuttle after aerial bombing (Catalina A of the 202 R.A.F. Squadron) and attack by the British destroyer H.M.S. Lamerton East of the Azores Islands. | ||

| Giuseppe Finzi | 9/29/1940 | 8/8/1943 | Transferred to Germany | ||

| Glauco | 10/22/1940 | 6/27/1941 | Scuttled after an attack from Wishart near Gibraltar | ||

| Guglielmo Marconi | 9/28/1940 | 10/28/1941 | Lost in the Atlantic probably off the Strait of Gibraltar | ||

| Guglielmotti | 5/6/1941 | 9/30/1941 | |||

| Leonardo Da Vinci | 10/31/1940 | 5/23/1943 | Sunk by depth charges by the frigates Active and Ness 300 miles off Vigo, Spain | ||

| Luigi Torelli | 10/5/1940 | 9/21/1941 | |||

| Maggiore Baracca | 10/6/1940 | 9/8/1941 | Bombed and rammed by the British destroyer Croome in Atlantic. | ||

| Marcello | 12/2/1940 | 2/22/1941 | Sunk in Atlantic by British destroyer Hurricane and Montgomery or, most probable, the Perwingle. | ||

| Michele Bianchi | 12/18/1940 | 7/5/1941 | Torpedoed by the British submarine Tigris off Bordeaux. | ||

| Mocenigo | 12/26/1940 | 8/23/1941 | |||

| Morosini | 11/28/1940 | 8/11/1942 | Probably sunk by a British plane in Atlantic | ||

| Nani | 11/4/1940 | 1/7/1941 | Probably sunk by the British corvette Anemone near Iceland | ||

| Otaria | 10/6/1940 | 9/14/1941 | |||

| Perla | 5/20/1941 | 9/28/1941 | |||

| Pietro Calvi | 10/23/1940 | 7/15/1942 | Scuttled at 0:27 AM after an attack by the British destroyer H.M.S. Lulworth near the Azores | ||

| Reginaldo Giuliani | 10/6/1940 | 9/8/1943 | Captured by the Japanese in Sapang, later manned by the Germans and sunk by the British submarine Tally-Ho | ||

| Velella | 12/25/1940 | 8/25/1941 | |||

| Veniero | 11/2/1940 | 8/17/1941 |

Photographic Memories of the Italian Presence in Bordeaux

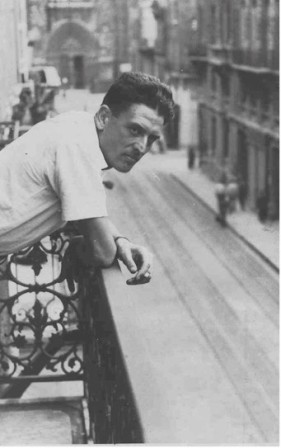

September 1st, 1941 – An officer is lighting a cigarette on a dock along the Garonne. In the background is the “pont transbordeur” which will be blown up by the Germans on August 18th, 1942.

(Photo kindly offered by Mr. Paolo Hoffmann)

38 Rue Viatal Carles – Bordeaux.

(Photo kindly offered by Mr. Paolo Hoffmann)

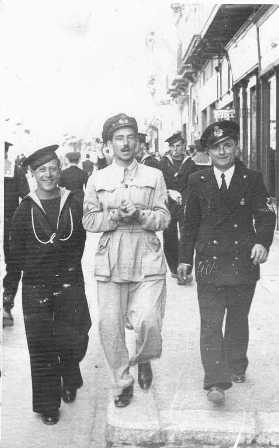

Cape Ferret (Arcachon) – July 3rd, 1941 In the picture are portrayed several officers in the company of German auxiliary personnel.

A: Chief Engineer C.G.M. Renato Filippini (Born in Trieste, 1906), who died aboard the R.Smg. DAGABUR on August 12th, 1942.

B: C.C. Franco Tosoni Pittoni, the officer who sank the British cruiser H.M.S. Calupso, lost aboard the R.Smg. BIANCHI on July 5th, 1941.

C: T.V. Mario Patane`, commanding officer of the R.Smg. VELELLA, lost on September 7th, 1943.

(Photo kindly offered by Mr. Paolo Hoffmann)

Otaria’s happy times: part of the crew of the Otaria.

(Photo courtesy Raccolta Romolo Maddaleni)

Cape Ferret (Arcachon) – July 3rd, 1941 C.C. Franco Tosoni Pittoni.

(Photo kindly offered by Mr. Paolo Hoffmann)

Submarine Emo – Mission from December 2nd, 1940 to January 2nd, 1941.

(Photo kindly offered by Mr. Paolo Hoffmann)

Sailors and petty officer.

(Photo Collection Dominique Lormier)

Italian submariners.

(Photo Collection Dominique Lormier)

Italian submariners.

(Photo Collection Dominique Lormier)

Marines of the Battaglione San Marco and a sailor in winter uniform.

(Photo Collection Dominique Lormier)

Sailors and marines of the Battaglione San Marco in Place Gambetta (Gambetta Square) downtown Bordeaux.

(Photo Collection Dominique Lormier)

2nd Chief Del Bubba with some comrades.

(Photo Rachele Granchi )

2nd Chief Del Bubba with some comrades.

(Photo Rachele Granchi )

2nd Chief Del Bubba with some comrades.

(Photo Rachele Granchi)

The integration of Betasom with the German Command Structure

Betasom was officially instituted on September 1st, 1940. Organizationally, it reported to two distinct commands: MARICOSOM (Marina, Comando, Sommergibili, or Navy Command Submarines) controlled personnel and technical and administrative functions, while SUPERMARINA controlled operations. MARICOSOM was created in 1939 following the reorganization of the “Comando Divisione Sommergibili” and was headquartered at the Ministry of the Navy, in a beautiful palace on the Tiber in Rome. The fact that this submarine base would operationally report directly to SUPERMARINA was an exception to the established practice and had been dictated by several factors. First, the size of the base (over 30 vessels) made it unusually large; second, the commanding officer was very senior in rank (a rear-admiral), and lastly, the base would be integrated with the existing German naval command structure.

Admiral Karl Dönitz visiting the Italian base in Bordeaux

In fact, to allow for a successful integration of the Italian forces with Admiral Donitz’s U-Boats, the Italian command issued the following directives: “For the coordinated deployment of submarines in war operations in the Atlantic, the group will receive directives from Admiral Donitz, Commander U-Boat Force”. The decision to integrate the Italian forces with the German ones had both tactical and organizational advantages. Tactically, the Germans did not have the required number of boats to properly impede British commercial traffic on a continuous basis; the Italian submarines would assist in providing this numerical advantage. Operationally, it would have been dangerous if the two forces had operated independently of each other, creating the real peril of dramatically increasing the possibility of losses due to friendly fire. After all, the Germans were not the only submarines operating in the Atlantic; British boats were always lurking along the coastline of occupied France.

Nevertheless, although officially reporting to the B.d.U., the German submarine command, the Italian base had a large degree of independence and the right to preserve Italian interests. Since the inception of the base, talented officers from both sides contributed to establishing a true spirit of comradeship. The first German liaison officer was Franz Hans Rosing, who was later replaced by Franz Becker. The Italian liaison officer to B.d.U. was Lieutenant Commander Fausto Sestini, who served for the duration of the conflict. The German command for the Atlantic coast was in Royan, a small city opposite La Pallice at the estuary of the Gironde, and it was later transferred to Nantes, much further north. The integration of the Italian forces called for the utilization of the existing German defenses, and the establishment of new ones. The port of Bordeaux and the shipyards were under the control of the Maritime Defenses of Guascony [Aquitaine] with headquarters in Royan.

The naval forces reported to the Kriegsmarine headquarters in Paris and were organized under the 4th Division and commanded by Kapitän zur See Lautenschlager who, in 1944, he was replaced by Kapitän zur See John. The Paris-based command was under Admiral Kranche, while the Maritime Defense forces were the responsibility of Vice-Admiral (Vizeadmiral ) Breuning. This high command of the Kriesgmarine was originally called Oberbefehlshaber des Admirals West, but after the 22nd of June 1940, it was renamed Oberbefehlshaber des Admirals Frankreich. This command was principally responsible for personnel and provisioning. The commanding officer was Admiral Karl-Georg Schuster until the end of February 1941, later replaced by Admiral Otto Schultze until August 1942, and then Admiral Wilhelm Marschall. Admiral Karl-Georg Schuster was the officer responsible for the first survey of former French installations along the Atlantic Coast and it is know that he visited the facilities later occupied by the Regia Marina.

Some of the minesweepers of the German 8th Flotilla

The 4th Division included the 8th Flotilla, organized in several groups. This flotilla was equipped with about 15 minesweepers of the M35, M39 and M40 type. They ranged from 755 to 908 tons in displacement and were armed with two 105 mm guns and antiaircraft machine guns. The 8th Flotilla was commanded by Kapitäleutnant Kamptz and was headquartered in Royan, but the vessels were distributed over several locations, and more precisely Royan, Pauillac, and La Pallice. According to Francis Sallaberry, the well-known Bordeaux-based author, there was also the 28th flotilla based in Pauillac and commanded by Korvettenkapitän Bidingmaier. This unit was also equipped with 15 minesweepers, but all of the M40 type. Naval defenses also included the very unusual 2nd Flotilla “Sperrbrecher”, often mentioned in the Italian documentation. These “obstruction breakers” were under the command of Kapitäleutnant Körner and based in Royan. The odd-looking fleet included former German, Norwegian, and French cargo ships ranging from a small one of only 480 tons, to the 7,090 tons former “Saurland”. These ships had been militarized with the installation of 105 mm naval guns, and 37 mm and 20 mm antiaircraft machine guns. Their task was to meet the submarines out at sea and escort them to safer waters by opening a path through the insidious magnetic mines launched by the Royal Air Force or deposited by the Royal Navy. They also provided escort for blockade-runners entering or leaving port.

The defense of the waterways around Bordeaux was the responsibility of the 4th flotilla, a group of about 28 smaller patrol and service vessels no larger than 500 tons and mostly imported from Germany. These vessels were armed with small machine guns and an 88 mm gun. The dockyards and the arsenal, as already mentioned, were the responsibility of the Kriegsmarine. The first commanding officer was Kapitäleutnant Siegfried Punt, who held the assignment until November 1942 and was later replaced by Kapitäleutnant Heinrich Wagner, who commanded until January 1944. During the period between January and August 1944, the commanding officer was Kapitäleutnant Carl Weber, an engineer.

The defense of the city of Bordeaux was instead the responsibility of the Wehrmacht. The area was organizationally under the 1st Army, and the local commander was Colonel Seiz, the military commander of Bordeaux, later replaced (1942) by General Knoerger. The port itself, including the submarine bases, remained under the Krigsmarine, while the airport of Merignac remained under the Luftwaffe. The Wehrmatcht built bunkers throughout the area, including three in Gradignan (Château Brandier), town later to become the base of the Italian command.

The defenses around the base included 88 mm and 75 mm guns and 20 mm antiaircraft machine guns, along with a number of searchlights.

The Port of Bordeaux

The autonomous port of Bordeaux (meaning an independently running organization marginally controlled by the state) included the smaller docking facilities at Le Verdon, Pauillac, Bec d’Amber and Basseurs. The port of Bordeaux, unusual for its location (well over 50 km from the sea), used to be a regular port of call for French, Dutch, British, Swedish, Norwegian and other merchant ships. Before World War II, traffic originated mostly from Morocco, the Antilles, French West Africa and Madagascar. Also considerable was the traffic from the United Kingdom, since one third of the total interchange consisted of coal originating from the British Isles, while the remaining goods included oil, peanuts, tobacco, and other raw products. Naturally, one of the most recognized trades was the export of the famous Bordeaux wines, mostly reds.

Orion arriving in Bordeaux.

(Photo Bundesarchiv)

The port of Bordeaux is fluvial and therefore prone to building up of sediments. The port authorities continuously dragged the river Gironde, thus guaranteeing access to the main channel to ships drafting up to 8.5 meters (25 feet) of water. Port facilities included several kilometers of “quais”, French for docks, and three dry-docks. Also parts of the facilities were three “bassin à flot” (tidal basins), enclosed waterways accessible through locks and protected from the tide. Although the port is over 50 kilometers from the ocean, the tide can move back and forth up to 6 meters (18 feet). Signs of this tidal shift can be easily seen along the river.

The locks leading to the tidal basin after the sabotage completed by the retreating German troops.

(Photo Bundesarchiv)

Access to the tidal basin from the Garonne was guaranteed by a set of locks leading to bassin à flot Number 1. The first basin led, through a small gate, to a second, and then a third. Also within the first basin there were two dry-docks, one measuring 105 meters and a second one 152. A third dry-dock, measuring 202 meters, was also available in the nearby naval yard.

Just before the French capitulation, Bordeaux was the de facto capital of the quickly dissolving French Republic. The port was used as a last resort for landing incoming troops, mostly colonial regiments, but also Polish troops, and it was also used to ship out gold from the national treasury. By June 23rd, the Germans controlled Royan, the seaside town facing Le Verdon across the opening of the Gironde into the ocean, thus virtually severing access to the city. A week later, on the 30th, the Germans occupied the city, and after a period of complete inactivity, the port reopened to commercial traffic, mostly to and from Morocco. Notably, the port was the final destination for most of the German and Italian “block raiders”, but by 1942 all traffic had ceased again, given that Allied interdiction at sea had become almost complete.

More damage along the quais.

(Photo Bundesarchiv)

By the time the Germans evacuated Bordeaux, several ships had been sunk to obstruct the port, amongst them the famous Italian block raider Himalaya. It would take the port authorities over one year to clear access to the docks, thus allowing for the first ship, one of the Liberty class, to call on July 18th, 1945. Today, the town of Bordeaux is demolishing the remaining docks, called “hangar”, giving room to a modern waterfront and opening the view to the splendid old buildings facing the “quai”. Most of the commercial traffic has been rerouted to the new port of Le Verdon, while Bordeaux is still visited by large cruise ships, which dock just in front of the old Royal Palace.

Château Raba

In 1774, Sara Raba, a merchant’s widow, driven from Portugal by the Inquisition, bought 80,000 “livres” from the daughters of Pierre Baillet the noble fief of Coudournes, also called the “Guionnet House”. In this house, according to tradition, Henri IV had slept the night before the battle of Coutras in 1587. The eight Raba brothers were all merchants except the third, who was a doctor.

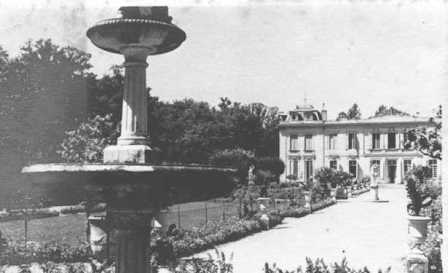

Château Raba

The Raba family demolished the Guionnet house to build the 18th century villa. It is a one-story rectangular building. At each end are two projecting pavilions covered by a “brisis” roofing. In the center, a porch with four ionic columns supports a coping. Above this, a balustrade forms a balcony. However, what is more original is a small low building at the end of the outbuildings, formerly a concert hall. The entrance, framed by Tuscan columns, supports a coping decorated with urns, in the center of which is a bas-relief representing a bust surrounded by beams of light.

Château Raba

Below this, a triangular pediment decorated with cherubs in the tympanum rests on large piles of bossage (stones that have been cut roughly and often laid into position for later finishing) This room was decorated with tapestries and many paintings. The villa itself was luxuriously furnished and decorated with art objects. But the interest of this villa resides especially in its park which gave Raba the nickname “Chantilly Bordelais.”

Château Raba

The lawns were decorated with statues and fountains; sphinxes guarded the chateau; paths lined with beautiful trees led to aviaries; there were hedges, a labyrinth and a pavilion of the Muses. There were also little constructions inhabited by automatons (robots) , a mill, a sheep pen, a little alms-house , a sort of truth machine, etc.

Details – Château Raba

Artificial animals, both domestic and wild, populated the area and sometimes frightened visitors. This was an amusement park ahead of its time and a kind of patronage, because the Raba family let strollers enjoy their property, even encouraging them to visit their salons and the music room. Celebrities came to visit the famous Chantilly. The Parliament of Bordeaux came as a group, as well as Beaumarchais and in 1808, Napoleon and Josephine.

Details – Château Raba

At the time of the Revolution, the Rabas were worried like all of those whose fortune attracted attention. But like the Peixottos, they got away with a fine and protestations of good citizenship. The Revolution needed merchants and bankers for supplies and most of them recovered their property.

Today the music salon and the orangery (greenhouse) inhabited by the family’s descendants, and the guesthouse, built later and rented to a Child Protection agency, are still in good condition. But the chateau itself, which has lost part of its roofing, is slowly falling into disrepair.

Translated, with the permission of the author, Ms. Francine Musquère, from the original French versions by Laura K. Yost. Originally published on “Talance à travers le siécles” in 1986

Châteaux

Soon after its establishment, Betasom attracted the attentions of the British Royal Air Force. The night of October 16th, 1940 the damage was very limited, but the night of December 8th, 41 aircraft dropped over 300 bombs, seriously damaging various civilian buildings, but causing almost no damage to Italian military installation. While French civilians suffered numerous casualties, only one Italian, a sentry of San Marco Battalion, (one book reports his name as Farina) was killed. The civilian areas particularly damaged were the Chartrons and Place Jean Juarès. The Chartrons is some distance from the Bassin à flot and more toward the center of town. Traditionally, this was the wine trading part of town. Even further away is Jean Juarès, a small square facing the scenic Quai Louis XVII and only a block away from the magnificent Place de la Bourse. As far as we know, the docks and the warehouses along them (called hangar) were not hit. Today, the “hangar”, or stock houses, along the Gironde are being demolished to give room to a larger road and a new trolley line. This area of the Quai is also used for docking large luxurious cruise ships during their call to the city.

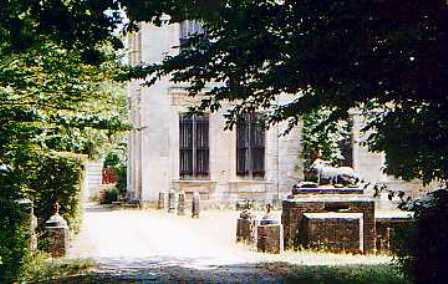

The bombardments missed the submarine base by well over 2.5 km, but forced the commanding officer, Admiral Parona, into seeking a partial relocation of the base. In collaboration with the German authorities, the Italians secured a few buildings at a safe distance from the base. The actual headquarter was moved to a small villa in the town of Gradignan, in a place called “Château du Moulin d’Ornon”.

Château du Moulin d’Ornon.

(Photo Cristiano D’Adamo)

This building, smaller than the nearby Château d’Ornon, was named after a mill which used to be located nearby. The edifice is still standing and it is in good condition. It is home to a medical facility dedicated to work related injuries. The interiors have been remodeled, but the small basement is almost frozen in time. By befriending the caretaker, who lives on the second story where the dormers are, one can visit the basement, including the original brick furnace and a newer one probably installed during this period. The first furnace dates back to construction time, probably the middle of the second half of the 19th century. The other, dating back to the 30s or 40s, is in a different room, and was probably converted from coal burning to oil.

Château du Moulin d’Ornon Annex.

(Photo Cristiano D’Adamo)

The château is not imposing; the entrance, a few steps away from the driveway, is small and placed in the middle of the building. Each side is adorned with two large window. The metal shutters, typical of this area, appear to be the originals along with most of the external hardware, including the two lamps. The back leads into a patio overlooking a delightful meadow contained by a brook and bamboo trees on the left and a small road to the right. Within a few yards, and facing the building at an angle, is a relatively large two-story building made of stones and bricks. The locals refer to the Château du Moulin as the “Italian generals’ villa”, and a nearby street is named the “Street of the Italians”.

Château du Moulin d’Ornon (Back).

(Photo Cristiano D’Adamo)

Officers were housed in two other château Raba and Tauzia, both located within the same general geographical area (Raba in in the town of Talence). Gradignan is just southwest of Bordeaux; today, it cannot be distinguished from the city itself. Sixty years ago, this small community was mostly agricultural and scarcely populated. Today, it is considered part of the city and it is well-known for its desirable neighborhoods and beautiful suburban homes. Local authorities and private owners have preserved the château although the Raba appears to be in a state of abandonment.

Tauzia is located near the Prieurè de Cayac (Abby of Cayac), famous for being one of the stops for pilgrims going to Santiago de Compostella. A long driveway, fenced by tall trees, guides the visitors up a small hill, arriving at the left side of the building. The actual entrance is to the right. From the large parking area a nicely designed landscape leads to the adorned entryway. Here, two large sets of twin columns support a small balcony covering the entrance to the single story central building. There are large windows adorning each side and architecturally merging the building with its two wings. These “wings” are two-stories tall and are roofed in the typical steep fashion of the local French Château. The building looks unchanged from pictures taken over sixty years ago.

The courtyard of the chateau

The property is not open to the public, and it is undergoing remodeling. The small dome behind the entrance was just completed and workers are now working on the façade opposite the entrance and overlooking a beautiful sloping meadow.

Château Raba

(Photo Cristiano D’Adamo)

The other facility, Château Raba, is fenced out and protected by dogs. Still, from the small square opposite the Ecole Supérieure de Commerce (Business School), one can see part of what must have been a glorious villa and which is now engulfed in weeds. The three villas are close, but not enough to walk. Today, the area is densely populated.

One of the barracks in Canèjan

The temporary housing used by the crew of the Otaria.

(Photo courtesy Raccolta Romolo Maddaleni)

The last two facilities, used by petty officer and sailors, were located in the Pinèdes of Gradignan and Canèjan. A Pinèdes is a small wood of Mediterranean pines planted in rows for the production of soft wood used in making quality paper. Crews were housed in small wooden barracks, which, considering the local climate, must have been quite cold in winter and hot in summer.

Bassin à Flot

Surprisingly enough, after so many years the area which once hosted the Italian and German submarine bases in Bordeaux are still recognizable and have not changed too much. The neighborhood is called Bacalan and it is still considered a rough part of town. This is a working class, industrial area that precedes the “hangar”, or piers. The piers are similar to the ones in San Francisco, but instead of extending into the water, are laid alongside the river.

One of the remaining hangar; this one will be left standing for historical reasons.

(Photo Cristiano D’Adamo)

The Bassin à Flot is a relatively large enclosed waterway connected to the river by two short navigable channels delimited by locks. The length of the access channels is slightly less than 200 meters, and the two channels are different; the one to the right is narrower and has three locks, while the one to the left is wider and has only two locks. Near each set of locks, there is a turning bridge pivoted on its center, and similar to the one in Taranto, but much smaller. These bridges, when opened, are aligned with the small island, which divided the two channels. The basin can only accept ships up to 152 meters long and 22 meters wide, large enough to allow for the Himalaya, the Italian “block raider” to be docked alongside the submarine base.

The Himalaya docked near Dry-dock N. 2.

(Photo Etablissement de conception et de production audiovisuelle des Armees)

The Bassin à Flot number 1 is shaped like a T with the base toward the river. To the left there is a large depot, or storage building. The original storage buildings are gone, but one of the block-houses (warehouses) was replaced by a newer construction fashioned in the style of the preexisting one and housing an insurance company. Part of the docks is still surfaced with the original “pave”.

The original pavè (cobblestone).

(Photo Cristiano D’Adamo)

To the opposite side of the storage area, one can find the two dry docks. The first one, larger and to the left, could host two boats, while the second, smaller, just one. Although it was suggested that vessels were docked head to toe, by looking at the facility it appears that they could also have been

placed side by side. The total surface area of the first basin is 11 hectares (110,000 sq. meters), while the second one is 9 hectares (90,000 sq. meters).

Clear signs of the great tidal change in the Atlantic.This picture is not of the port of Bordeaux, but La Rochelle.

(Photo Cristiano D’Adamo)

The Bassin à Flot can only be accessed from the river during high tide. Once the river recedes, as the Garonne does twice a day, the water level inside stays constant, while outside it decreases quite considerably. At the other end of the basin is another lock leading onto Bassin à Flot N.2. This second Bassin is quite recognizable from a distance because it hosts the German-built submarine pens. The location is referred to as the “Base sous-marine”, or submarine base, and today, it is the home of a museum dedicated to sailing.

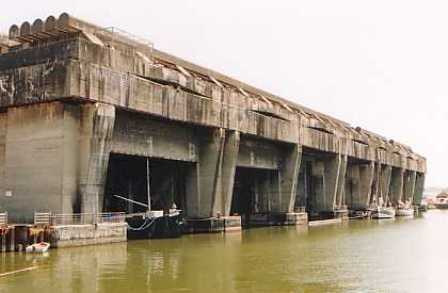

The German bunker used by the Submarines of the XII Flotilla U-Boot.

(Photo Cristiano D’Adamo)

This construction, at times also used by the Italian submarines, is massive; the cost of dismantling it would have been so great that the city decided instead to use it. From the parking lot facing Blvd. Alfred Domey, one can still see some of the damage caused by Allied bombing. This was the facility used during the filming of the movie “Das Boot”, even though in the movie the U-Boat was not based here with the German XII Flotilla U-Boot.

The Bombardments of Bordeaux

The city of Bordeaux was first bombed by the Germans the night of June 19th when a formation of 12 Heinkel 111, avoiding the local air defenses, reached the heart of the city. Despite the intervention of the French Air Force’s Bloch 152s, the Luftwaffe was able to easily penetrate the new French capital causing 65 casualties and 160 wounded. The mission was intended as a stimulus for the French government to quickly finalize armistice negotiations. Within a few days, on June 30th, the French government would do precisely so.

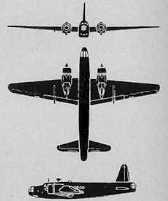

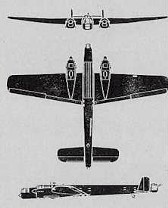

Following the fall of France, and with the beginning of the Battle of England, the Royal Air Force (R.A.F.) was not particularly interested in the Aquitaine capital and the city experienced a few months of tranquility. With the reopening of fluvial navigation along the Gironde, and the arrival of the first Italian submarines, the situation gradually changed; the British began paying attention. At this point in time, the R.A.F. offensive forces (bombardment groups) consisted of Wellington I/IA, Whitley III/V and Hampden aircraft organized into three bombardment groups, the 3rd, 4th and 5th. These groups were based in East Anglia, Yorkshire and Lincolnshire. None of these aircraft was fast, armed and maneuverable enough to avoid the German fighters, especially the newer Me 109. Also, these airplanes suffered from the absence of modern navigational systems and crews had to rely on sextants and astrocompasses.

The first British bombardment of Bordeaux area was aimed at the refineries and oil storage facilities in Bec d’Ambès and Pauillac and it was quite successful; well over 70,000 tons of oil products were destroyed. A second bombardment followed the night of October 16th, when 12 Hampdens belonging to the 44th (Rhodesia), and 49th Squadrons (5th Group) took off from Waddington and Scampton. Two airplanes aborted the mission due to foul weather and returned to base, while the remaining aircraft continued on with their cargo of 900 Kg marine mines (Deodar). Of the remaining planes, four delivered their cargo while the other six experienced various breakdowns, with one airplane simply disappearing. The mission was a partial failure.

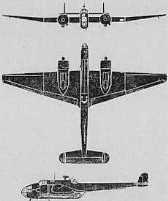

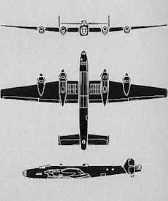

Vickers Wellingtom II

(Span: 86ft. 2in. – Length: 61ft. – Max Speed 244 m.p.h. @ 17,000 feet)

Armstrong Whitworth Whitley

(Span: 84ft. – Length: 72ft. 6in.- Max Speed 221 m.p.h. @ 17,750 feet)

Handley-Page Hampden

(Span: 69ft. 4in. – Length: 53ft. 7in.- Max Speed 247 m.p.h. @ 13,800 feet)

Handley-Page Halifax

(Span: 99ft. 11in. – Length: 71ft. 7in. – Max Speed 262 m.p.h. @ 17,750 feet)

The night of November 2nd a larger number of Hampdens, along with some Blenheims, returned to the city: in total 32 airplanes. The primary target was the airport of Merignac where 4 hangars and 6 airplanes were destroyed. Amongst the airplanes destroyed were two large four-engine German Kondor K 200s, the so-called scourge of the Atlantic. The night of December 8th witnessed a real show of force: 44 R.A.F. aircraft were sent to Bordeaux. The formation included 29 Wellingtons of the 49th (5th Group), 149th and 115th Squadrons (3rd Group), and 15 Whitleys of the 4th group. This time the target was the city itself and more specifically the Italian submarine base at Bacalan. The bombardment lasted over 5 hours and was facilitated by excellent weather conditions.

Focke-Wulf F.W.200 Condor, one of the prime target for the borbardments.

(Photo Bundesarchiv)

In the luminescent night, the “Bassin a Flot” (tidal basin) was perfectly visible and the Wellingtons dropped their bombs from altitudes ranging from 1500 to 3600 feet. Each airplane was loaded with 8 to 13 112 Kg bombs, while the Witleys were instead loaded with 225 and 122 Kg ones. During the bombardment, the German mixed ship (cargo and passengers) Usaramo was hit and it settled on the muddy bottom of the Garonne. Also lost was the tanker Cap Hadid, which caught fire, while the large French passenger ship De Grass was only marginally damaged. This ship had been previously damaged during a German bombardment, but once again it survived. The Italian base, and especially the submarines, had received minimal damage.

The Usaramo was muddy bottom of the Garonne.

(Photo Collection Ando)

The civilian population instead suffered the brunt of the punch; 16 casualties and 67 wounded. Most of the bombs fell at about 2500 to 3000 meters from the base toward the center of the city (Bacalan is to the north). British losses were minimal, only aircraft T2520, a Wellington of the 115th Squadron, was lost near Cardiff along with its 5 crewmembers.

Bordeaux: bombardment of civilian quarters

The year 1940 closed with two more bombardments, one on the 26th and another one the following night on the 27th of December. These two attacks focused principally on the airport of Merignac, west of the city. The second was quite substantial; well over 70 aircraft participated, but there was no report of any Focke-Wulf 200 “Kondor” being destroyed.

In March 1941, the Air Ministry decided that the airport at Merignac would be a much more important target than the naval base in Bacalan and so future attacks would primarily focus on the airport. After a long pause, British bombers reappeared the night of April 10th. Once again, the target was Merignac where 11 Wellington cause much damage: two hangars demolished, two FW 200 destroyed, two Heinkell II also destroyed along with a Dornier 215. The R.A.F. lost one bomber. Meantime, aerial reports from British fliers informed the High Command that the number of submarine in port was substantially increasing. A report dated June 22nd, 1941 cited 22 vessels. Fortunately for the Italians, the R.A.F. did not take action.

The following year, 1942, witness very little activity. The night of July 14 and August 5th, Halifaxes from the 83rd Squadron dropped mines along the Gironde. Reports about these attacks can be found in the local newspaper “La Petite Gironde”. The newspaper was quite vehement in denouncing these bombings, which inevitably caused great harm to the civilian population. Removing mines would require some time, but the navigable channel within the Gironde was relatively small, thus allowing for quick de-mining.

The left side of the tidal basin completely demolished.

(Photo USMM)

The year 1943 opened with a new raid the night of January 26th. Nine British Halifaxes belonging to the 6th Group targeted the submarine base at Bacalan. French sources report civilian casualties in the area or rue Achard. With the arrival of the US 8th Air Force the situation changed. The much more sophisticated American bombers made their debut on May 17th, at 12:38 PM in full daylight. Thirty-nine B-24s belonging to the 44th and 93rd bombing group left Davidstow Moor in Cornwall four hours earlier and flaying at an altitude of 2500 feet reached Bordeaux where they dropped 342 250-kg bombs. The damage was substantial: a bomb hit the German submarine bunker causing minor damage (still visible today) while the tidal basin was heavily damaged. One of the two turning bridge spanning the entrance channels was demolished, and so was one of the two sets of locks. The left side of the tidal basin was completely demolished for a length of over 400 meters. Water rushed out of the basin leaving a few submarines grounded into thick mud, but causing minimal damage to the vessels.

Bombs had fallen almost perfectly perpendicularly to the dock causing most of it to sink into the water. The antiaircraft battery 9/22 was hit causing total devastation. Typical of WW II bombing, collateral damage was staggering: cours Saint-Louis and cours Balguerie-Stuttenberg were devastated. The French population has to endure 200 casualties and 300 wounded. The damage to the Axis forces was minimal, the Heer (army) claims 4 dead and 3 wounded, the Luftwaffe 1 dead and 9 wounded, the Kriegsmarine 10 dead and 23 wounded, the Regia Marina 4 dead and 3 wounded, the Todt Organization (in charge of military constructions) 3 dead and 1 wounded. Only one American airplane was lost.

Bordeaux: collateral damage.

(Foto collezione Andò)

August 24th, 58 B-17 targeted Merignac (Bombing Groups 94, 95, 96, 100, 385, 388, 390). All aircraft returned to their North African bases. Hereafter, American missions become more and more frequent involving more B-17s, P-38s and finally P-51 Mustangs. Raids would become more and more massive, like the one of March 27, which included over 700 B-17 and B-24. During this mission alone, the airport of Merignac was targeted by over 540 tons of bombs. By then, the Italian base had ceased to exist and all submarine operations were under German control.

Merignac: the aerostation completely destroyed.

(Photo ECPA)

For the record, the RAF return to the Aquitane skies in late April with Lancasters and Mosquitos. They would come back the 4th of August alternating bombing missions with the Americans. At the end, Allied missions found very little opposition; most of the German 88 mm anti-aircraft batteries had been quickly redeployed to Normandy to halt the Allied invasion. Bordeaux has suffered 545 houses destroyed and 341 damaged. The port was completely unserviceable, gas and electricity severed. It would take months to reopen fluvial navigation and years for the city to recover. Meantime, memories of the Italian submarine base quickly vanished.

The Italian submarine base in Bordeaux, France

On May 22nd, 1939, the Kingdom of Italy and the German Reich signed a new military pact (Pact of Steel) that linked the future of the two nations. Following the signing of the pact, and as part of the negotiations, the Italian high naval command met with their German counterparts in Friedrichshaffen (Germany) on the 20th and 21st of June, 1939 to discuss the terms of naval collaboration.

This alliance was quite strange in nature, and it can be seen as the result of the most unusual historical development of the European geopolitical scenario following the conclusion of World War I. As the first few months of co-belligerence demonstrated, the alliance between Italy and Germany was mostly political and economical, while military collaboration was minimal. German political and economical supremacy would inevitably be reflected in military affairs, and therefore the Italian government was well intended to maintain a parallel course with the Germans, avoiding direct military collaboration. The two allies were not equal; Germany had an impressive industrial apparatus which, even during the war, increased production, while Italy, a country mostly agricultural, had a limited industrial capacity and a chronic shortage of prime goods.

Italian submarines in Bordeaux.

(Photo U.S.M.M.)

The Friedrichshaffen meeting did not generate much momentum; Germany failed to transfer radar technology to her new ally, while Italy limited her exchange to selling advanced thermal torpedoes to the Germans. Naturally, very soon it would be the Germans selling advanced electric torpedoes to Italy along with any technologically essential equipment. During these meetings, Admiral Cavagnari, the Italian equivalent of the First Sea Lord, committed to an Italian presence in the Atlantic. For a navy, which had been specifically built for a strictly Mediterranean war, this commitment was a stretch. Still, Italy had built high displacement submarines capable of crossing the Strait of Gibraltar, reaching the Atlantic for long patrols, and then returning home. During the 1939 discussions, the glamorous successes of German U-Boot during World War I were still vivid in the minds of all naval strategists. Italy, which during World War I had mostly fought in the Adriatic, not only had expanded her range of action to the Mediterranean basin, but was also considering operating in both the Atlantic and Indian Oceans.

With the Italian expansion in East Africa, despite the limited docking facilities, one would have expected a forceful Italian presence in the Indian Ocean and Red Sea to impede British maritime traffic. Unfortunately, due to poor planning, defective equipment and waning supplies, the fear of an Italian menace in the area failed to materialize. Later, Italian submarines will, once again, appear in the Indian Ocean, but this time originating their journeys from the Atlantic coast of France.

On the Atlantic side, and especially in 1939, no one expected the availability of docking facilities. Spanish support, although much sought after, never materialized and therefore there weren’t any other friendly harbors available. Italian and German submarines would have had to sail from their home bases, thus allowing only for very limited patrols. The Italians had to deal with the Strait of Gibraltar and the local British presence, which, despite Spanish pro-axis tendencies, still gave the Royal Navy a dominant control over the narrow passage. Nevertheless, Italian submarines would cross the strait numerous times without any major incident.

With the unexpectedly rapid fall of France, the Germans suddenly gained access to the Atlantic and its many ports. Although the U-boot fleet was at this time very limited in number, its technical advantages were enormous. Germany would immediately begin an unprecedented building program which would soon dwarf the Italian submarine fleet, at the time the second largest in the world. In accordance with the agreement reached a year earlier, in 1939, immediately after Italy’s entry into the war, the German naval command requested an Italian presence in the Atlantic. As originally agreed, the Italian vessels would patrol the area south of Lisbon, while the German would patrol the area north of the Portuguese capital. The division would have avoided complicated coordination between the two navies, and would have also favored the Italian vessels in terms of climatic conditions.

An Italian military commission visited various French ports along the Atlantic coast and, after easy negotiations with the Germans, the choice fell on the inland port of Bordeaux. This was an unusual selection, but it proved to be an excellent one. Bordeaux is almost 50 miles from the Bay of Biscay to which it is connected by the river Gironde. The same river is also connected to a sophisticated system of navigable canals, which connects it to the Mediterranean. Bordeaux had good docking facilities, including dry docks, repair shops, and storage depot. All these facilities were in a state of abandon, but unscathed by war and easy to restore to service.

(Photo U.S.M.M.)

Like all Italian military bases, the one in Bordeaux needed a telegraphic address. At the time, telegraphs (and teletype) were the primary means of communication. The name chosen was a simple one: B for Bordeaux and SOM as an abbreviation for “Sommergibile,” submarine in Italian. In the Italian military world, the letter B was called “Beta”, just like our “Bravo”; the combination of the two created the name BETASOM. This name would enter the history books to signify a lesser known, but very important page of submarine warfare. All communications from BETASOM were routed by the Germans via Paris or Berlin. There was no direct line from the base to Rome. To establish direct communications, the Italians installed several powerful radio apparatuses aboard the liner De Grass.

The French liner De Grass.

(Photo U.S.M.M.)

The Italian submarine base occupied a constant level basin connected to the river Garonna by two lock gates. The basin included two dry docks, one large enough for the ocean going boats, and a second one capable of servicing two smaller submarines at once. To the right of the lock gate pumping station sat the cafeteria and quarters for the troops belonging to the San Marco battalion. Immediately after, also on the right side of the basin, lay the two dry docks and behind them the repair shops and depots. The basin was shaped almost like a T .

The base was officially opened on August 30th, 1940 with the arrival of Admiral Perona. Other offices included the Chief of Staff C.F. Aldo Cocchia, (Capo di Stato Maggiore), the base commander C.F. Teodorico Capone (Comandante della Base), the officer responsible for all communications C.C. Bruno de Moratti (Capo Servizio Communicazioni), the officer responsible for all operations C.C. Ugo Giudice, and several other officers. The Germans assigned two liners to the Italians, the French De Grass (18,435 tons) and later in October the German Usaramo (7,775 tons).

A view of the” bassin”

(Photo U.S.M.M.)

The De Grasse, in addition to the already mentioned radio station, was used as a military infirmary, while personnel with serious conditions was sent to the local French hospital. The De Grasse was moored only a few hundred yards from the basin near the transatlantic passenger station. This large concrete building was quickly turned into barracks capable of hosting about 750 sailors. Nearby buildings were used for office space, storage, and other uses. The entire area was fenced and patrolled internally by 225 soldiers of the San Marco battalion and externally by German troops. The Germans, who had installed six 88 mm guns and forty-five 20 mm machine guns, provided for antiaircraft defenses. The Germans also provided for all antiaircraft detection services, and patrols along the Gironde and the Bay of Biscay.

The basin was capable of hosting up to thirty submarines. Each dock was equipped with the necessary infrastructure to provide vessels with fresh water, compressed air and electricity. Power to the base was provided by generators brought on purpose from Italy and by the local grid. The local repair shops did not have the equipment and machinery necessary for precision work aboard submarines, and much was shipped from Italy, along with 70 specialized technicians.

Later, the base began utilizing French personnel, but it always limited access to the vessel only to Italian workers. Despite the fear of sabotage, the relationship with the local work force was overall very positive. Despite the miserable living conditions and the German occupation, the base did not experience any act of violence or sabotage.

An aerial picture of the facilities in Bordeaux, France.

(Photo U.S.M.M.)

Since, as we have already mentioned, the base of Bordeaux was quite far from the ocean, the Italian command set up a smaller base in La Pallice, near La Rochelle on the Bay of Biscay, about 50 miles north of the estuary of the river Gironde. It was equipped with a dry dock and a few temporary accommodations for up to three submarine crews, and was utilized only for smaller repairs and tuning. The base in Bordeaux, since it is a fluvial port, did not have the facilities to test submarines underwater. This testing was done in the Bay of Biscay, but a return trip along the 50 miles from the ocean to Bordeaux would have caused the loss of much time. Naturally, the work performed in Palluce was usually simple. This base was also used as the last stop before leaving for a mission and as the first one upon returning.

The fifty miles from the ocean to Bordeaux were quite treacherous. A local French pilot was always employed in bringing the units safely up and down the river. Since the Gironde has a noticeable tidal excursion, admittance to the basin was allowed only during high tide (twice a day). Also, navigation along the river was much safer during high tide, even though the navigable channel was clearly marked and the river often dragged. Considering that submarines have a very shallow drought, tidal excursions were never a factor, despite the fact that in this area they average 18 feet.

After the creation of the Italian base, several French ports were the targets of heavy aerial bombardment. Eventually, on October 16th and 17th, even Bordeaux became victim of these British attacks. Admiral Perona, responsible for the over 1,600 personnel at the base, decided to spread out some of the personnel. This decision was reinforced by a new British bombardment which took place on the 8th and 9th of December. This time, over 40 planes dropped a large number of bombs and mines. Damage to the Italian base was limited, but shrapnel hit the De Grass while the Usaramo was sunk.

Several essential services were dispersed in a range of about 9 miles from the base. The ship Jaqueline, used as an ammunition depot, was moored further away from the base, while part of the torpedo ordnance was transferred to Pierroton. The De Grasse was vacated and moved further away from the base. Headquarters were relocated to Villa Moulin d’Ormon, while officer quarters were rearranged in the castles of Robat and Tauzien. The remaining personnel were housed in a summer camp in Gradignan.

The base would remain fully operational until September 8th, 1943 when, after the Italian armistice, it was occupied by the Germans. Thereafter, some Italian personnel opted to continue fighting alongside the Germans, but Italian command was never re-established. It should be noted that while the Germans built concrete pens for their boats in Bordeaux, the Italian submarines where always exposed to aerial attacks. Despite this weakness, not a single vessel was lost in port or along the Gironde to aerial attacks.