Although Alexandria was to produce the most famous success for the 10th Light Flotilla, the several attacks against the British bastion of Gibraltar, known as “The Rock”, were the most successful ones conducted by the unit. On September 24th, 1940, in the same period when the British destroyer Stuart sank the Submarine Gondar (on its way to Alexandria) in the Gulf of Bomba, the Submarine Scirè left La Spezia for a parallel mission against Gibraltar.

I

This mission planned to violate the British base of Gibraltar utilizing a few human torpedoes, the so-called “maiali” (Italian for pigs). The four crews chosen were: Lt. Teseo Tesei and P.O. diver Alcide Pedretti, Lt. Gino Birindelli and P.O. diver Damos Paccagnini, Sub-Lt. Duran de la Penne and P.O. diver Emilio Bianchi, with Sub-lt. Giangastone Bertozzi and P.O. diver Azio Lazzari in reserve. The mission was under the overall command of the Scirè’s commander, Captain Junio Valerio Borghese.

View of Gibraltar from Algeciras

This was the first war mission of the Scirè under Borghese and, as he narrates in his book “Sea Devils”, he acquainted himself quite well with the crew. Lt. Antonio Usano, from Naples, was the second in command, while Lt. Remigio Benini was the navigation officer. Also aboard were midshipman Armand Alcere, the torpedo officer from Liguria, and Lt. Bonzi, later replaced by Naval Engineer Lt. Antonio Tajer, the chief engineer.

Villa Carmela

Borghese also credits Ravera, the chief mechanic, Rogetti the chief electrician and Farina, the chief gunner. Most of this crew would be lost, several months later, with the sinking of the Scirè off the Israeli cost when Borghese was no longer in command. On September 29th, at about 50 miles from the target, Supermarina recalled the Scirè due to lack of suitable targets. The submarine arrived at La Maddalena, in Sardinia, on the 3rd of October.

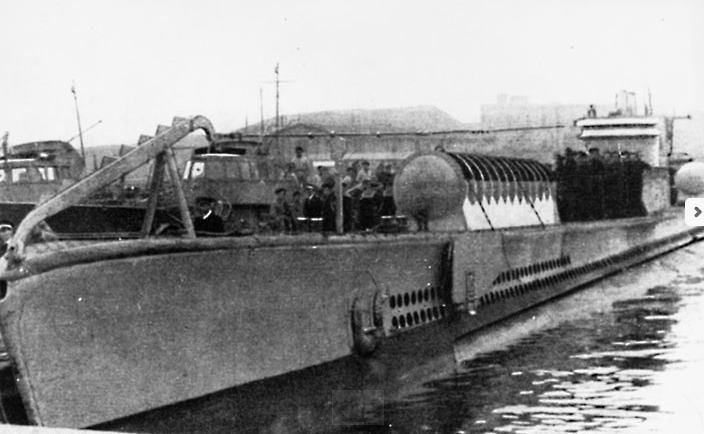

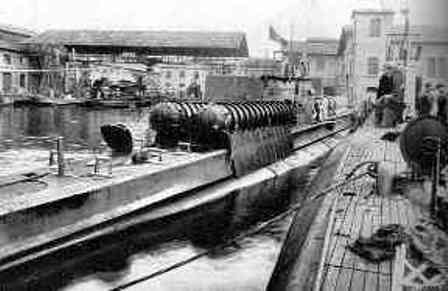

The submarine Scire

II

On October 21st, the Scirè left La Spezia for a second attempt against Gibraltar. On the 27th, the submarine reached the strait of Gibraltar, where Borghese twice attempted an approach while surfaced, and twice British escorts chased him off. Finally, on the 29th, the Scirè broke through, and taking advantage of the strong current, entered the Bay of Algeciras. On the 30th, the Scirè came to rest at a depth of about 45 feet near the estuary of the river Guadarranque. Six members of the 10th Light Flotilla manned the three “pigs” and left the submarine, which safely returned to base on the 3rd of November.

The first team, De la Penne – Bianchi, was detected by defense vessels and bombed. The human torpedo failed, sinking quickly to the bottom, while the two crewmembers were able to swim back to Algeciras where Italian agents picked them up. Soon after, they were flown back to Italy. The second team, Tesei – Pedretti, despite some minor problems with the “pig”, made it to the North Mole. Here, problems with the breathing apparatuses forced the abandonment of the mission. Like the first team, they made it safely to Spain and then back to La Spezia. The third team, Birindelli – Paccagnini, experienced the same technical problems with both the torpedo and the breathing equipment. The crew had almost reached the battleship Barham when the “pig” lost power. Birindelli attempted to drag the heavy explosive near the target, but exhausted, he had to abandon the mission. After an adventurous escape attempt, the officer was finally captured, joining his diver who had been captured in the harbor. What followed for the two men was three years of hard imprisonment.

The mission had been a failure, but it had planted the seed for future successes. Much had been learned, especially regarding the behavior of the equipment and its technical shortcomings. Borghese and Birindelli were awarded the Gold Medal (equivalent to the British Victoria Cross), while the other frogmen received the Silver Medal.

III

The third attempt to penetrate Gibraltar witnessed an important change in strategy. Prior missions called for the operators to travel with the submarine from La Spezia to the target. These few days at sea, in very cramped conditions and under continuous threat of attacks, caused severe physical repercussions. Thanks to an elaborate intelligence network, the Regia Marina was able to organize a pickup point in the port of Cadiz. The assault teams were sent ahead to Cadiz under false pretenses where they would board the 6,000-ton Fulgor, an Italian tanker interned at the beginning of the war.

On the 23rd of May, the Scirè moored alongside the tanker and boarded the four teams; Lt. Decio Catalono and P.O. diver Giannoni, Lt. Amedeo Vesco and P.O. diver Toschi, Sub. Lt. Licio Visentini and diver P.O. Magr and the reserves, Lt. Antonio Marceglia and diver P.O. Schergat. This time, the company surgeon, Bruno Falcomatà, joined the mission to attend to the crew.

On the 25th, after several crash dives to avoid detection, the Scirè reached Algeciras, but it did not enter the bay until the following day. Franchi was sick and he was replaced. The crews were sent off as usual and the Scirè returned to base in La Spezia on the 31st. Once again, the mission was hampered by technical mishaps. Ultimately, none of the targets was reached, but the crew reached the safety of Spanish territory. All crew members received the Silver Medal and more invaluable experience was acquired.

IV

After the devastating disaster at Malta, Borghese was appointed as the interim commander of the 10th Light Flotilla. Once more, the Scirè was called upon to deliver men and materiel for an attack against Gibraltar; this time it would be a successful one. The operational plan was similar to the one used during the previous mission. The submarine was to pick up the operators from the Fulgor in Cadiz. The teams were almost the same as GB3; Lt. Catalano with diver Giuseppe Giannoni, Lt. Amedeo Vasco with diver Antonio Zozzoli, Lt. Visentini with diver Giovanni Magro and Eng. Captain Antonio Merceglia with diver Spartaco Schergat in reserve. This time, the surgeon was sub. Lt. Giorgio Spaccarelli.

Early on the morning of the 20th, the crews left the Scirè, which returned to La Spezia on the 25th. The first team, Vesco – Zozzoli, was able to attach their warhead to the 2,444-ton Fiona Shell which, after the explosion, split in half and sank. The second team, Catalano – Giovannoni, reached a cargo and attached the warhead to then realize that the vessel was actually an interned Italian ship, the Pollenzo. The charge was removed and used to sink the 10,900-ton armored motorship Durham, which promptly sank. The third team, Visintini – Magro, failed to enter the harbor due to continuous surveillance. This was a problem already experienced by the two other teams. Nevertheless, in the outer harbor they were able to mine and sink the naval tanker Denby Dale, which weighed 15,893 tons. A small tanker moored alongside went down as well.

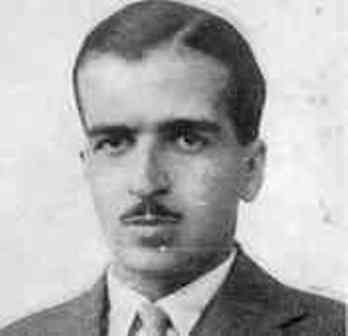

Licio Visintini

Finally, after so many disappointments, 30,000 tons of enemy shipping had been sunk. The human torpedoes had proven their worth, despite the fact that a newer model, also produced by the “Officine San Bartolomeo” had already replaced the one used during this mission. Borghese, recently promoted, was elevated to the rank of Captain, while the assault teams, all of whom reached the safety of Spain, were awarded the Silver Medal. The entire crew of the Scirè was also decorated and received special treatment, similar to that received by the crew members of the German U-Boot, which was soon to be extended to the entire submarine fleet. Emotions ran high. The King himself wanted to meet the now famous prince Borghese. After an audience in Rome, Victor Emanuel, whose countryside estate bordered the 10th Light Flotilla base near the estuary of the river Serchio, paid a private visit to the unit at the Tuscan base. Borghese later wrote: “This was the last time I saw the King”.

V

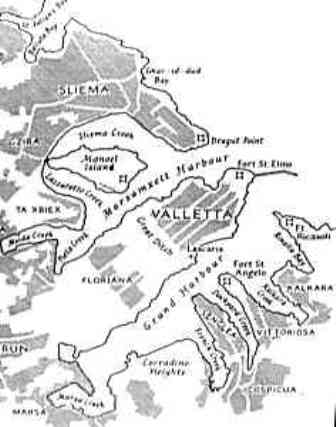

While the 10th Light Flotilla was investigating new tactics, an Italian technician, Antonio Ramognino, was sent to Spain to survey the Bay of Algeciras. Taking advantage of the fact that his wife, Signora Conchita, was a Spaniard, the Ramognino rented a small house near the Maiorga Point overlooking the bay and Gibraltar. Under the false pretense of Conchita’s poor health, the couple settled in the house and started what appeared to be a very quite life. The house, which came to be known as Villa Carmela, quickly became the secret operational base of many attacks against the Rock.

In July 1942 several swimmers, lead by the former champion yachtsman Agostino Straulino, were smuggled into Spain. The group of 12 men included: Sub-Lieutenant Giorgio Baucer, petty officers Carlo Da Valle, Giovanni Luccheti, Giuseppe Feroldi, Vago Giari, Bruno di Lorenzo, Alfredo Schiavoni, Alessandro Bianchini, Evideo Boscolo, Rodolfo Lugano and Carlo Bucovaz.

By several means, the group reached Cadiz and boarded the Fulgor. From here, on the 11th and 12th the group was transferred to the Olterra in Algeciras. On the night of the 13th-14th the action began: the group left Villa Carmela protected by darkness, reached the nearby beach and began the long swim toward Gibraltar. They were carrying limpet mines, which would be attached to the hull of ships moored in the outer harbor.

The Olterra

On the way back, seven of the swimmers were arrested by carabineros once they reached the shore, but later released to the Italian consul in Algeciras, Signor Bordigioni. The remaining swimmer, one way or another, made it all the way back to Villa Carmela and from there to the Fulgor to then be repatriated. The result was good; the 1,578-ton Meta, the 1,494-ton Shuma, the 2,497-ton Snipe, and the 3,899-ton Baron Douglas were sunk for a total of 9,468 tons. All the swimmers were awarded the Silver Medal for gallantry.

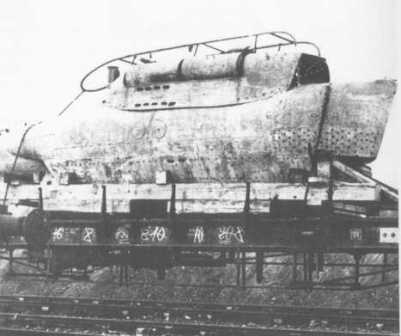

The secret machine shop on the Olterra

VI

The success of the previous mission brought about a new attempt. The dismay caused by the sinking of so many ships had generated much speculation amongst the British authorities. This time, the number of swimmers was much smaller. On the night of September 15th, Straulino, Di Lorenzo and Giari defied the increased British watch and sunk the 1,787-ton Raven’s Point. The operation was not a full success and demonstrated that surveillance in the harbor had been dramatically improved.

VII

While swimmer operations were being conducted, Visintini continued working on the Olterra on a plan to convert the interned ship into a secret base. An underwater chamber was carved out of the hull of the ship, thus allowing for the unnoticed release and recovery of human torpedoes. The weapons, weighing more than two tons, were disassembled in smaller parts and shipped from La Spezia to Algeciras as repair components for the Olterra. The first assault would be led by Visentini himself who had Giovanni Magro as his second, and by Sub-Lieutenant Vittorio Sella, Sargent Salvatore Leone, Midshipman Girolamo Manisco and P.O. Dino Varini.

Salvatore Leone

On December 7th, Visintini led a three-team assault into Gibraltar. The human torpedoes left the hull of the Olterra at a one-hour interval from each other. The British defenses had been stiffened and underwater bombs were dropped all over the bay at regular intervals. Visintini and Magro could not reach their target and perished, probably hit by the explosion of a depth charge. Manisco and Varini were the object of a long pursuit which ended with the sinking of their craft. The two found refuge aboard an American cargo ship where they were warmly welcomed by a crew of mostly Italian-Americans. Cella and Leone, despite the general alarm and a continued pursue by British patrol boats, headed back to the Olterra where Cella discovered that his companion Leone had disappeared; he had perished.

Vittorio Cella

The mission was a debacle; three had died, two were prisoners and only one had made it back. The only redeeming news was the fact that the British, in a communiqué dated December 8th, thought that the men had arrived aboard the submarine Ambra: the secret of the Olterra had not been revealed. The bodies of Visintini and Magro were later found by the British and buried at sea with military honors. Visintini was awarded the Gold Medal, an honor which he shares with his brother, an aviator, who also died in combat.

Giovanni Magro

VIII

On May 1st 1943, Commander Borghese replaced Commander Forza at the helm of the 10th Light Flotilla. Italy’s war fortunes were definitely on the decline: East Africa was lost and so was North Africa. The Regia Marina was on the defensive and the only unit truly on the attack was the 10th Light Flotilla.

In Algeciras, after the loss of Visintini’s group, the so-called “Great Bear” unit was being rebuilt. Lieutenant-Commander Ernesto Notari took over command and was joined by P.O Diver Ario Lazzari, Lieutenant Vittorio Cella and P.O. Diver Eusebio Montalenti. Soon after the arrival of the new crews, equipment was shipped from Italy using the same expedient of camouflaging the dissembled pigs as spare parts for the Olterra. The tragic experience of December 8th had taught the 10th not to attempt another break into the inner harbor, but to focus on the less protected outer one.

The secret machine shop on the Olterra

The night of May 7th 1943, in the midst of a severe storm and taking advantage of the lunar phase, the three teams (Notari, Todini, Cella) took to the sea, at one-hour intervals from each other, and mastered their human torpedoes across the bay. They mined several ships using extra warheads for the first time carried by the pigs. They all managed to return to the ship from which they could easily watch the fruits of their labor. The 7,000-ton Pat Harrison, the 7,500-ton Marhsud and the 4,875-ton Camerata blew up and sank. Once again Gibraltar was at the mercy of the 10th Light Flotilla.

IX

On the night of August 3rd 1943, the “Great Bear” Flotilla, still under the able command of Notari and mostly comprised of the same crews, left the Olterra for a new mission. Notari, whose second was a lesser trained diver by the name of Giannoli, experienced technical difficulties with his torpedo. The pig suddenly dived and, when he thought that all was lost, reemerged in an uncontrollable upright burst. In the process, the two crew members separated with Notari able to make it back to the Olterra and Giannoli, after a two-hour wait, forced to surrender.

One of the limpet mines used the swimmers

A British search squad was immediately dispatched to the U.S. ship near which Giannoli had been captured, but they were too late and could only witness a devastating explosion which sank the 7,176-ton Harrison Gray Otis. Cella was able to mine and sink the 10,000-ton Norvegian tanker Thorshoud, while the third team sank the 6,000-ton British ship Stanbridge.

Epilogue

The Olterra, still undetected by the British, was going to be part of a combined operation which contemplated a simultaneous attack by MTRs and human torpedoes when, on September 8th 1943, Italy surrendered. The 4,995-ton ship had been a real success story. Surprised by the declaration of war on June 10th 1940, it had been sunk by its crew in shallow waters.

It was later identified by the 10th as a possible secret base. In 1942, with the excuse of refitting the ship for sale to a Spanish shipowner, the vessel was re-floated and brought back to Algeciras for refitting. Here, under the tightest secrecy, personnel from Italy built an internal flooded pool, which was connected to the sea. They also built a complete shop capable of assembling and maintaining the human torpedoes.