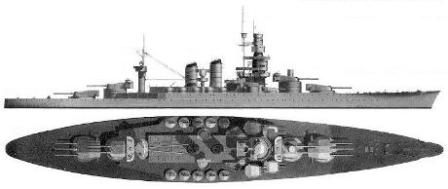

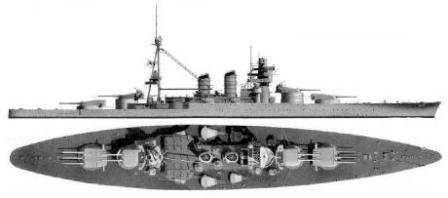

Conte di Cavour and Caio Giulio Cesare

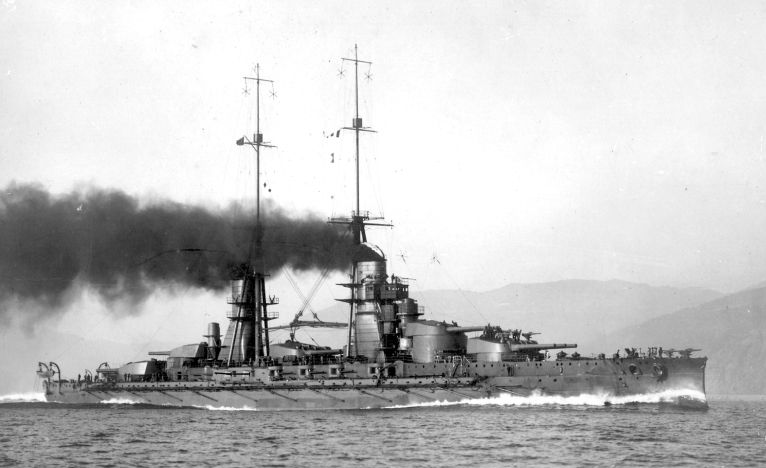

During the last world conflict, the Italian Navy utilized three distinct class of battleships, two of which were modernized vessels dating back to World War I (Conte di Cavour and Duilio Class) and one of new construction (Vittorio Veneto or Littorio Class). The Cavour Class dated back to 1909 when, by royal decree, Italy ordered the construction of three battleships: Conte di Cavour, Caio Giulio Cesare and Leonardo da Vinci. The three battleships were delivered to the Navy in 1914 (the Cavour was actually completed in 1915). This article will focus on the modernization of the original design performed in the 30’s because , besides retaining the original hull, the ships should be considered mostly completely new.

The Conte di Cavour before the modernization

Victorious after the epic but bloody battles of World War I, Italy’s economy entered a period a deep recession and eventually depression similar to many western countries. The enormous financial expenditures of the conflict, and the heavy reliance on foreign imports, had left Italy nearly bankrupt. During this period, Italy retained the Cavour, Cesare and the two battleships of the other class, Doria and Duilio in the naval reserve. The Leonardo da Vinci had been lost due to Austrian sabotage.

With foreign powers building new battleships – Germany with the Deutschland (technically a pocket battleship) and France with the Dunkerque (technically a battle cruiser) – it was strategically and military impelling for the Italian Navy to respond with similar vessel to provide for a balance of power. Construction of new units was at this point financially prohibitive, thus a study was initiated to modernized the existing battleships. In spring 1933, Admiral (E) Francesco Rotundi [i] and the ‘Comitato Progetti Navi’, the bureau in charge of naval constructions, began a project to transform the Cesare and Cavour assigning the contract to Cantieri del Tirreno in Genoa (Cesare) and C.R.D.A. in Trieste (Cavour). Over a period of four years, more than 60% of each vessel was completely replaced. The end result was more powerful armaments, higher speed, increased protection, and a radically new, and more elegant silhouette.

The Hull

With the original hull completely emptied – only the external hull was left untouched – the inside was fully redesign to give room to decompression cylinders of the Pugliese type. These devices were particularly designed to absorb the impact of underwater explosions by providing a protected expansion chamber. Technically, the two options available were to either build anti torpedo protections external to the hull, similarly to the Barham, or internally as it was decided. The design chosen provided for a better shaped hull, thus retaining speed which, at the time, was considered a critical advantage over foreign units.

The original Pugliese cylinders tested on the ships Brennero and Tarvisio had to be reduced in size, and thus effectiveness, due to the limited space available. At the same time, a double hull bottom and lateral compartments were greatly improved, even though they were not able to save the Cavour from the sinking in shallow waters of December 11th, 1940 in Taranto due to the unusual location on the explosion directly under the hull. In that case, the explosion wave, reflected by the bottom of the harbor, magnified the devastating effects causing massive structural damage. To reduce costs and construction time, the old style bow was left in place and a new, modern shaped one fitted on top of it. Astern, two of the four axels were removed, but the overall shape was left untouched.

The belt armor was left at 250 mm, but the base of the turrets (barbettes) received an additional 50 mm of de-capping plates. The new control and command tower was protected by 260 mm of steel, while the deck, originally protected only by two layers of 12 mm, received an additional 80 mm of protection.

Decks

The decks were named:

Ponte di Coperta (Upper deck)

Primo Corridoio (First Desk)

Second Corridoio (Second Deck)

Copertino Superiore (Upper Deck)

Copertino Inferiore (Lower Deck)

Piano di Stiva (Hold)

Engine

The power plant was completely replaced removing the old 4-propellers, 3-turbines, 12-boilers systems producing 31,000 HP, with a modern 2-propeller, 2-turbines, 8-boilers system producing 75,000 HP. The boilers were of the Yarrow type and equally distributed between seaside and portside. The 22 kg/cm2 steam powered the Belluzzo system which incorporated a high pressure and two low pressure turbines.

The power plants were offset, one forward and one aft, and could receive steam from any of the boiler systems. Prove of the reliability of this system was given during the Battle of Punta Stilo (Action of Calabria) when the Cesare, hit by a British 381 mm projectile, was left with only four functioning boilers, but was able to operate, even though at a lesser speed, on both power plants.

At the sea trials, the power plants were discovered to have much more power than the originally contracted values propelling the units to the becoming the faster battleships of the time.

Electricity

With the introduction of several new electrical instruments, the electrical system was redesign and the old steam dynamos replaced by more powerful power generating units operating both off the main boilers’ steam and also on diesel fuel. The diesel units guaranteed powered even in case on a complete failure of the boiler system. Both vessels were equipped with two redundant gyrocompass of the latest generation with 12 repeaters each. There were both protected and unprotected radio shacks and four 120 mm Galileo projectors. These battleships were never equipped with radar equipment, even though there was a study conducted in 1943 to equip the Cavour with a German or Italian apparatus.

Armament

The most creative part of the modernization process took place around the main artillery. The original Armstrong Vickers [ii] 305 mm guns were considered grossly inferior to what other navies were utilizing, but the cost for total replacement was prohibitive. The original guns, which were made of an outer shell, coiled steel cables and an inner shell, or riffled tube, were disassembled. The coil was reduced in thickness by Ansaldo in La Spezia and the inner tube replaced with one of greater caliber bringing the guns up to 320 mm (12.6 “). This new gun was designated as the Ansaldo 320 mm/44 1934. This technically challenging alteration resulted very successful as the lateral resistance of the gun barrel, while weakened, was not compromised. Furthermore, the elimination of the fifth turret, located amidships, gave extra material for the alteration. At the end, the battleships were left with 10 guns each, three on the lower gun turrets and two on the upper ones, five aft and five forward.

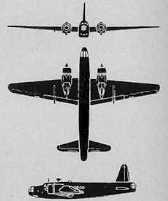

320 mm guns

The 320 mm guns had a maximum elevation of 27˚ and a maximum depression of -5 ˚and a range of 28,600 meters. The projective weighted 525 Kg. and had a speed of 830 m/sec (meters per second) at the muzzle. The rate of fire was 2 rounds per minute. The length of the barrel was 48.8 calibers or 15.616 meters. Each gun weighted 64 metric tons.

The medium caliber 120 mm guns were completely eliminated as well as the 76/50 mm and the 76/40 mm. The medium caliber were replaced with twelve 120/50 mm disposed in six dual turrets. These were naval guns with a very limited elevation and primarily used for defense against torpedo boats. The limitation of these guns became apparent only during the conflict when the primary foe was enemy aircrafts rather than light ships. These guns had a weight of 2 metric tons with the projectile weighing 15 kg. The muzzle velocity was 850 m/sec with a rate of fire of 9 rounds per minute and a maximum range of 15,240 meters.

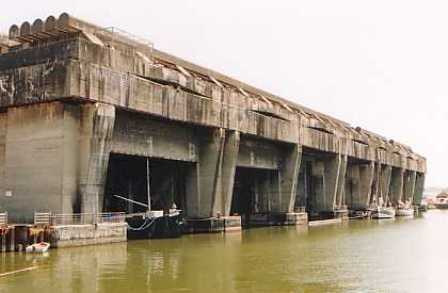

Cavour 120/50 mm disposed in a dual turrets

Antiaircraft protection was provided by eight 100/46 mm OTO 1928 guns disposed in four dual positions. There were also twelve 37/54 mm anti aircrafts guns also in dual positions and augmented by twelve 13.2 mm antiaircraft guns. In 1940 the smaller guns were found highly limited and replaced by Breda 20/65 mm. During the conflict, in 1941, the Cesare received additional antiaircraft protection bringing the total number of the Breda 20/65 mm to sixteen.

Ammunitions

All ammunitions were kept in four distinct magazines located under the armor deck and near the turrets. The magazines could be easily flooded and were accessible to the outside via a modern system of rolling doors. The standard ordnance included 800 shells for the 320 mm guns, 2,900 shells for the 120/50 mm, and 2,460 for the 100/47 mm.

The transfer of the large projectiles from the magazine to the guns was complex and very secure. Projectiles were picked up via electric winches and deposited on a loading dock. Subsequently, four begs containing the charges were added and the full charge elevated to the guns. The charges were introduced into the guns, after the projectile, two each time. The whole system was automated, excluding the initial handling of the powder bags.

The smaller guns did not have this complex but efficient system, but were rather loaded by hand. Each gun had a small reserve of about 24 projectiles. Antiaircraft guns were provided with protected cases containing up to 18,000 rounds.

Firing Control

The firing control mechanisms and apparatus was completely replaced and substituted with modern equipment which proved itself up to the task for the duration of the conflict. The main telemetry system was housed in a movable compartment located 23 meters above the waterline and positioned above the main control tower. Due to its unusual shape, it was quickly nicknamed the ‘Carabiniere’s Hat’. There were two telemetry systems each 7.20 meters wide.

The so-called ‘carabiniere’ hat

The telemetry station was connected to the firing station which could control all guns automatically and fire them at once. In case of failure of the automated system, there was a failover station incorporated in gun number 2 (forward) and a 9 meters wide telemeter. Smaller guns and antiaircraft guns had their own independent aiming and fire control mechanisms.

Aircraft

Originally, the class was equipped with two catapults, but the four RO 43 on board turned out to be more of a nuisance to general operations than a valid scouting tool, and thus they were disembarked. This lack of aerial reconnaissance never impacted these battleships, but it was an overall weakness of the fleet at sea.

Paint

Like all other vessels in the navy since 1929, the Cavour Class battleships were painted light gray. During the conflict, after study conducted on methods to make the enemy’s telemetry more difficult to focused, and based on a design by the well-known painter Claudius, the ships received a mimetic paint schema. The original schema (1941) was later altered and the colors reduced from three to two (light and dark gray).

Specifications

The Cavour class had a nominal displacement of 28,800 tons (29,032 metric) with a length of 186.4 meters, a width of 28.028 and a draft of 10.4 meters. Armor represented 33.9% of normal displacement. The nominal power of 75,000 HP was calculated to be during trials as high as 93,000 HP. The maximum speed during these trial was 28.2 knots (28 on the Cavour) with propellers rotating at 237 rpm on the Cavour and 241 rpm on the Cesare. At the time of trials, this class resulted the fastest in the world. Maximum speed at sea was about 27 knots, but the machinery could be stressed up to 28 knots. The ships had a range of 6,400 miles at 13 knots, 3,084 at 20 knots and 1,700 at 24 knots. The bunkers could hold up to 2,472 tons of fuel.

The crew consisted of 36 officers and 1,200 between petty officers and sailors.

Conclusions

A debate over the option to modernizing these two ships versus building a new one – as it later happened with the Vittorio Veneto Class – still rages. The limitation of the Cavour Class compared to the more powerful British battleships was quite evident during the Battle of Punta Stilo (Action of Calabria) were the Italian 320 mm could not compete against the British 381 mm. Still, the Cesare withstood a full hit without losing its fighting power. Eventually, only the Vittorio Veneto (LIttorio) Class battleships represented a serious threat to the British Navy. Thus, one has to conclude that building a single, more powerful battleship would have been preferable, but considering the technological innovation, the ingenuity and the results achieved, much credit has to be given to the Italian naval engineers who collaborated on this project. Let’s not forget that the Cesare, after the conflict, was ceded to the Soviet Unions as part of the Italian war restitution plan and that, renamed Novorossiysk, served until 1955 when it was lost due to an explosion in shallow waters. This longevity gives credit to its design and construction.

Credits:

Franco Bargono, Franco Gray – Edizioni Bizzarri – 1972

‘LE NAVI DI LINEA ITALIANE’ Giorgio Giorgerini and Augusto Nani, USMM – 1962

[i] Rotundi (Foggia, 10 July 1885 – Rome, 25 October 1945) is universally known for having designed the Italian training ship Amerigo Vespucci.

[ii] Armstrong Vickers 12” 1909. There are some references to some of the guns being produced by Elswick and designated Pattern “T”. Both utilized Welin breech-blocks.