The Aradam was a Class Adua, “600” series, Type Bernardis, coastal submarine (displacement of 698 tons on the surface and 866 tons submerged). Along with the twins Adua, Alagi and Axum, it differed from the other units of the class for the engines: CRDA, both diesel and electric (while on the other boats the electric engines were from Marelli, and the diesel, some from FIAT and some from Tosi).

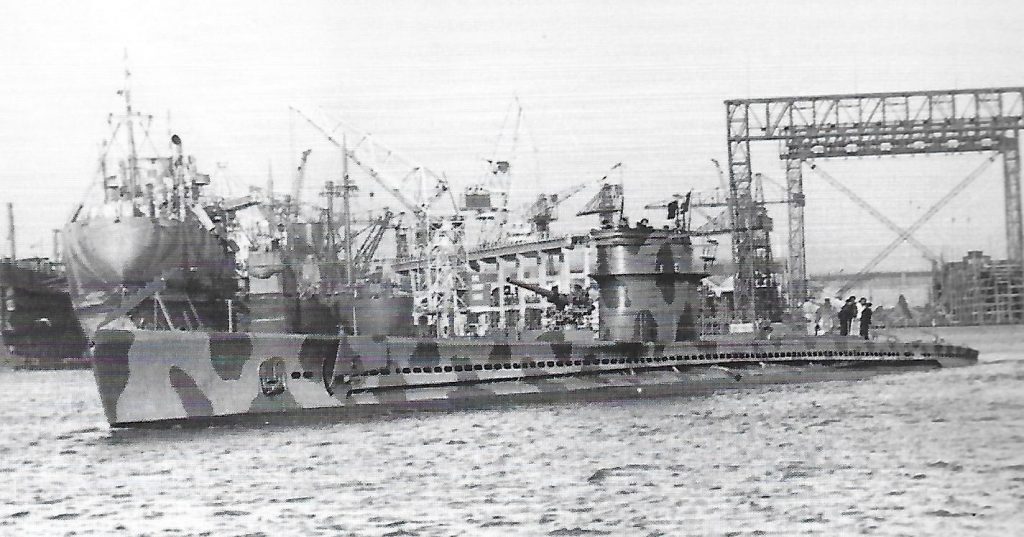

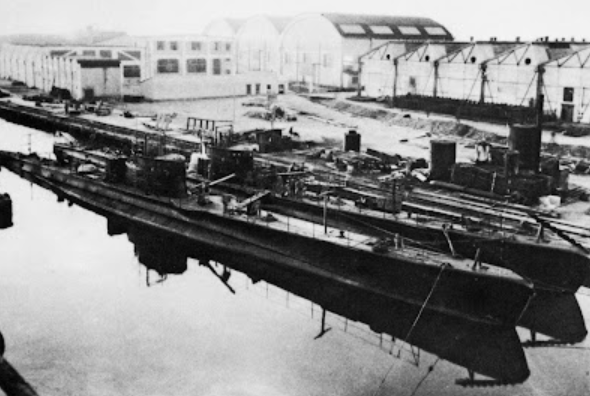

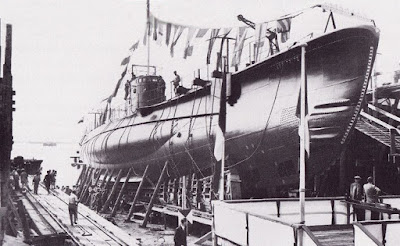

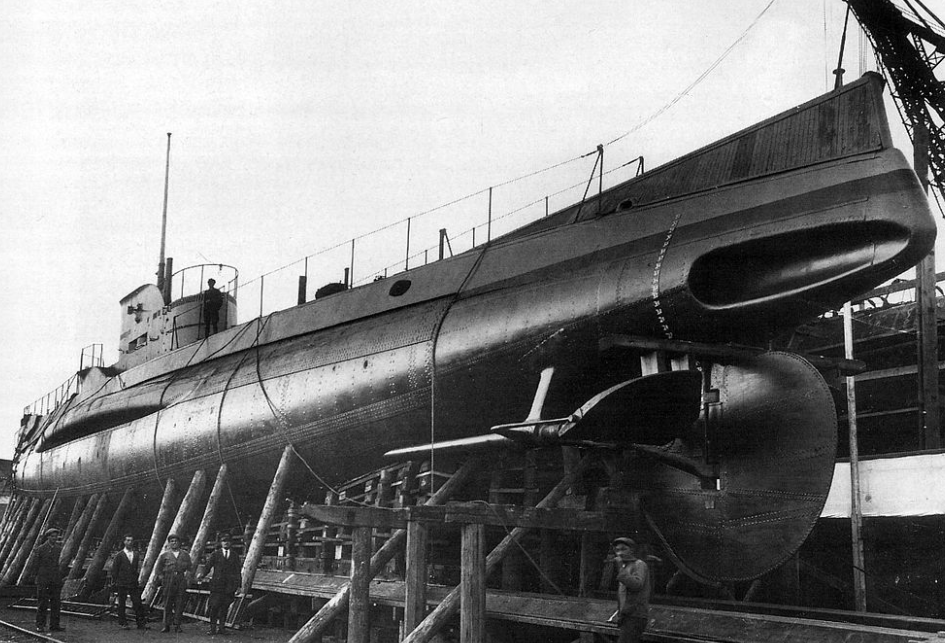

Aradam early configuration with a fully enclosed conning tower

(Colletion Bonadies)

During the war, it completed a total of 50 patrols (30 offensive/exploratory and 20 transfer), covering 26,144 miles on the surface and 3,223 submerged, and spending 280 days at sea.

Brief and Partial Chronology

March 14th, 1936

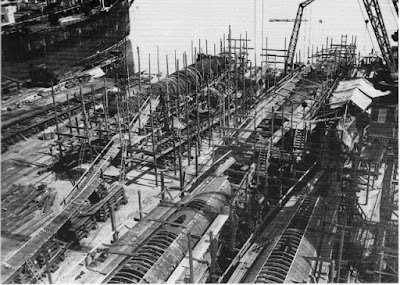

Laid down at the C.R.D.A. (Cantieri Riuniti dell’Adriatico) in Monfalcone (construction number 1179).

October 18th, 1936

Launch at the C.R.D.A.

January 13th, 1937

The boat entered active service. In the first months, it was at the disposal of the Submarine Squadron Command (Maricosom).

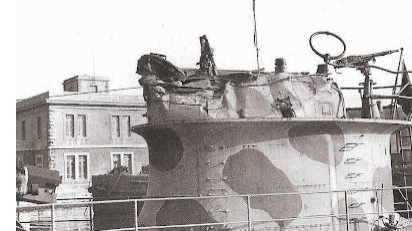

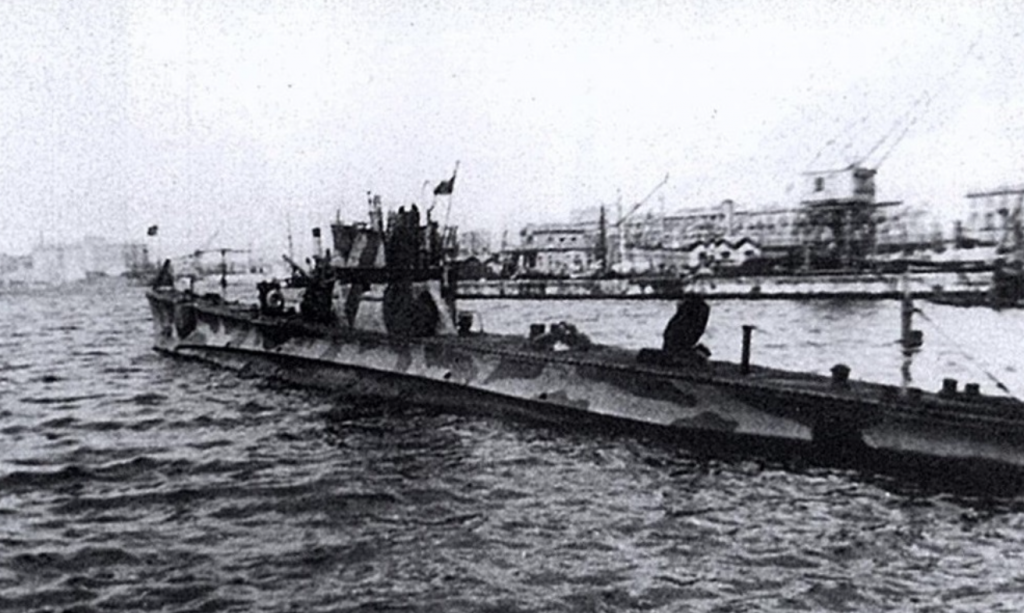

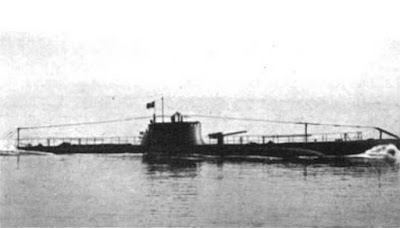

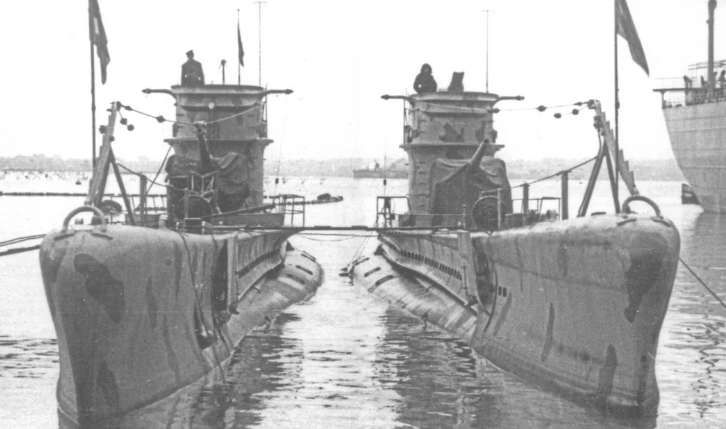

Aradam and the twin boat Alagi in Monfalcone

(From “I sommergibili classe 600 serie Adua” dbyAlessandro Turrini, published on “Rivista Italiana di Difesa” n. 3, March 1986)

March 6th, 1937

The boat was assigned to the XXIII Submarine Squadron, based in Naples. The commander, at the time, was Lieutenant Gino Spagone.

1937-1940

The Aradam completed training cruises between Tobruk, Benghazi and the Dodecanese.

May 5th, 1938

Under the command of Lieutenant Massimo Alesi, the Aradam took part in the naval magazine “H” organized in the Gulf of Naples for Adolf Hitler’s visit to Italy. The Submarine Squadrons were the protagonist of one of the most spectacular moments of the parade, in which the 85 boats carried out a series of synchronized maneuvers. First, at 1.15 PM, arranged in two columns, they passed opposite course two naval squadrons proceeding on parallel routes. Then, at 1:25 PM, all the submarines made a simultaneous dive, proceeded for a short distance submerged, and then surfaced simultaneously and fired a salvo of eleven shots with their respective guns.

1939

The commander of the Aradam was transferred to Lieutenant Mario Signorini, from Rome.

December 20th, 1939

Lieutenant Commander Giuseppe Bianchini, 32, from Palermo, replaced Lieutenant Signorini.

June 10th, 1940

Italy entered the World War II. The Aradam was part of the LXXI Submarine Squadron of the VII Grupsom of Cagliari, along with the sister boats Adua, Alagi and Axum.

It was sent on patrol south of Sardinia and north of the island of La Galite (according to another source, the boat was already lurking at the time of the declaration of war).

June 14th, 1940

The Aradam returned to Cagliari without having encountered any enemy ships.

June 21st, 1940

The boat was sent on patrol in the Gulf of Lion to attack French traffic heading to North Africa. The Aradam noticed numerous aircraft on anti-submarine patrol boats, which it interpreted as a sign of the passage of a convoy.

June 23rd, 1940

At 3.12 AM, in position 42°40′ N and 04°25′ E the crew sighted an unidentified light unit, probably believed to be French, proceeding at high speed. It launched a torpedo at the unit, which did not hit due to the unfavorable launch conditions.

July 1940

The boat was sent off Gibraltar and it did not observe any enemy units.

August 1940

Another mission in the waters of Gibraltar, again without encountering enemy units.

October 1940

The Aradam was sent off the island of La Galite (on a 315° bearing from the island), and was subsequently ordered to move about 60 miles north of Cap de Fer (Algeria) and then moved again 45 miles west of La Galite.

October 27th, 1940

At dawn the crew sighted a destroyer and avoid any engagement by diving.

November 9th, 1940

In the late afternoon, the unit leaved Cagliari heading into the waters north-northeast of the island of La Galite to form a large barrage (along with the Alagi, Axum, Medusa and Diaspro) southwest of Sardinia to contrast operation “coat”.

The Aradam, and the other four boats, were positioned at 315° bearing from La Galite, 30 miles apart, with the task of carrying out night search on a parallel course without going more than 120 miles west of the line of formation. Supermarina (Admiral Domenico Cavagnari) ordered Maricosom (Admiral Mario Falangola) to form this barrage in the western Mediterranean after having already formed another one southeast of Malta with the submarines Topazio, Pier Capponi and Fratelli Bandiera.

The purpose of the barrage, of which the Aradam is part, is to intercept Force H, which, according to reports from French and Spanish aerial reconnaissance was sailing towards the Strait of Sicily. According to another source, Force H was located on the morning of November 9th by the Regia Aeronautica following the air attack against Cagliari launched by the Swordfish of the Ark Royal.

Cavagnari’s order (no. 1772, very urgent and delivered by hand), in particular, states: «Arrange that five submarines be ready to leave Cagliari at sunset today executing, during the night, a transfer to a barrage line oriented from La Galite to the northwest (stop) Submarines at a distance of 30 miles from each other on the aforesaid line will remain in deep hydrophone ambush during the day and will perform during night hours ambush on the surface moving by parallel within the limits of the initial line and parallel line moved 120 miles to the west (stop) Purpose is to attack enemy naval forces moving in the waters between Sardinia and the Balearic Islands (STOP) During the night 2 torpedo tubes are to be kept ready at each end (stop) Units will return to order (STOP) secure (STOP) Cavagnari».

Consequently, in the early hours of November 9th, Maricosom ordered the VII Grupsom based in Cagliari, with message number 43846, to send five submarines (among those chosen there was the Aradam) which were to position themselves parallel to the northwest of La Galite, moving at night, sailing on the surface, and 120 miles to the west. The Aradam did not spot any enemy ships.

November 14th or 15th,1940

After having just returned to Cagliari, in the evening, the Aradam is sent out again, along with the Alagi and a third submarine, the Diaspro, to counter operation “white”. The Aradam did not spot enemy ships.

November 18th, 1940

The unit returned to base.

November 25th, 1940

The boat was sent south of Sardinia along with the submarines Axum, Diaspro, and Alagi, following the sighting by an Italian civilian aircraft of the British Force D. The Aradam did not spot any units.

January 1941

The Aradam was sent on patrol north of Bizerte and 40 miles east of La Galite.

January 9th, 1941

At 5:20 PM, the crew detected propeller noises on the hydrophone, and, twenty minutes later, it was subjected to an anti-submarine hunt by three enemy units, a hunt that lasted until 7:20 PM.

April 1941

During the first half of the month, the Aradam was sent on patrol off the Cyrenaic-Egyptian coast.

July 29th, 1941

Lieutenant Commander Bianchini relinquished the command of the Aradam and was replaced by Lieutenant Oscar Gran, 32, from Trieste.

Late July-early August 1941

The Aradam was sent, along with three other submarines (Alagi, Diaspro, and Serpente), lurking in ambush southwest of Sardinia in contrast to a British operation. The Aradam’s patrol is completed without any enemy units being sighted.

September 3rd, 1941

The Aradam was sent on patrol off the coast of La Galite.

September 25-29, 1941

The Aradam was sent on patrol in the Tunisian’s waters. The boat was ordered to move east of the Balearic Islands (in the Sardinian Sea, between Sardinia and Menorca) and south of Menorca (precisely, in the Menorca Channel and north of Cape Bougaroni) to create a barrage along with three other submarines, Axum, Diaspro and Serpente.

October 1941

The Aradam was sent on patrol about 60 miles east of La Galite.

November 1941

The Aradam was sent to ambush 45 miles northeast of Tunis.

December 1941

The Aradam was sent for another ambush in the waters of the Galite.

December 19th, 1941

The Aradam was sent on patrol to the north of Algeria, along with the Alagi, and further east than Tricheco and Axum (which have been deployed off Cape Bougaroni), in anticipation of a possible entry of Force H into the Mediterranean.

January 3rd, 1942

The boat was sent to lie in wait south (or east) of Malta, in the area between the meridians 14°40′ E and 15°20′ E and the parallels 34°00′ N and 34°20′ N, with the task of sighting and attacking any British naval forces that might take to the sea.

February 10th, 1942

The Aradam was sent as part of a barrage in Algerian waters. There, it detected on the hydrophone and then sighted a naval formation heading east, reporting it to the General Commands (according to another source, however, it only detected it on the hydrophone, without being able to spot it).

March 1942

The Aradam was ordered on a patrol in the waters of Cape Bougaroni.

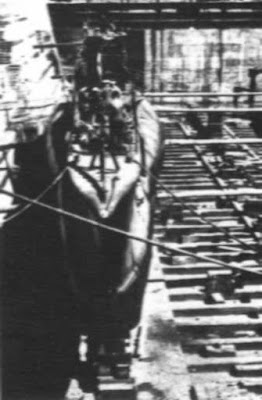

The Aradam in Cagliari. Note the mimetic painting scheme.

(From the magazine Storia Miltare)

March 27-29, 1942

The Aradam was sent to lie in wait in the Strait of Sicily along with the submarines Narvalo, Turchese and Santorre Santarosa, to intercept Force H (under the command of Admiral Neville Syfret), which had left Gibraltar and headed eastwards, should it make it that far.

April 1th, 1942

At 00.45 AM, in position 38°29′ N and 07°40′ E (southwest of Sardinia), the Aradam was sighted on a 240° bearing, while proceeding on the surface with a 340° course, by the Dutch submarine O 23 (Lieutenant Commander Albertus Marinus Valkenburg). The Dutch vessel maneuvered to get closer, remaining on the surface, but in doing so it was spotted by the Aradam, which immediately dove at 00.52 AM not being sure if it had sighted a friendly or enemy unit. At 00:54 the O 23 also dove and managed to detect the noise of the Aradam engines on the hydrophones, but without being able to establish the exact distance and bearing; after an hour of fruitless submarine hunting, at 1:56 AM, O 23 emerged and resumed navigation towards Alexandria.

April 4th, 1942

At 1.03 AM, having finished embarking provisions the previous evening, the Aradam (Lieutenant Oscar Gran) left Cagliari along with another submarine, the Turchese, for an ambush in Tunisian waters, with the dual purpose of protecting the Italian convoys bound for Libya from incursions of the British naval forces based in Malta, and of attacking any isolated British traffic that might cross these waters.

The ambush area of the Aradam was east of Cape Kelibia, the one of Turchese north of Cape Bon. Maricosom Operation Order (209/SRP of 3 April, 7.45 PM) established: “Confidential personnel (STOP) Executive ambushes Kappa one submarine Turchese and Kappa two submarine Aradam (STOP) Turchese submarine outward route number one (STOP) return route number four with return to Trapani new location (STOP) Aradam outbound route number one (STOP) return route number five with return to Trapani new location (STOP) Leave ambush to order (STOP) Partial modification of the general order of operation Kappa during ambush during daylight hours, remain perched on the bottom without coming periscope depth for listening to SITES (STOP) instead of sunset day five, arrive on ambush points as soon as possible after having performed hidden navigation daylight hours day four“.

April 5th, 1942

The Aradam reached the assigned area, east of Kelibia (east coast of Tunisia), not far from the lighthouse of the same name and south of Cape Bon, and began the patrol.

April 6th, 1942

At 3.12 AM the second in command of the Aradam, Second Lieutenant Edoardo Burattini, at that time on duty on the bridge, sighted a dark silhouette with an estimated course to the south, and summoned Commander Gran to the bridge; the silhouette soon turns out to be that of a large destroyer sailing westwards with a route that passed the Cape Bon peninsula at a beta angle of 25° to starboard and about 2,400-2,500 meters away.

Commander Gran gave orders to take a new route to intercept the enemy unit. The rapid drop in distance indicates that the enemy ship was proceeding at low rpm, which is why he decides to idle the engines. The destroyer passes between the Aradam and the Tunisian coastline at a sufficient distance to allow it to be detected with the Panerai (a sort of range finder). At 3:17 AM, having reached position 37°47′ (or 36°47′) N and 11°05′ E and a distance of less than 500 meters, thus suitable for launch and subsequent rapid disengagement, Commander Gran ordered two torpedoes to be launched from tubes 3 and 4, setting for a depth of three meters and a course angle of 15° to starboard.

However, while the torpedo of tube number 3 came out regularly, the one in tube 4 did not start due to the malfunction of the electric launch system. Moreover, the noise caused by the Aicardi mechanism for the recovery of the compressed air bubble generated by the launch, covered the manual launch order given from the bridge to the chief torpedo operator, who already worried by the rapid dive signal, had consequently closed of the outer caps of the launch tubes.

No explosions were heard. While the crew worked to restore trim which had been altered by the change in weight due to the launch (a maneuver complicated by the particularly shallow waters in which the Aradam found itself). Commander Gran decided to place the submarine on the seabed, while the hydrophones were carefully monitored for any sources of noise, which lead to fear that there could have been a second British unit in the area, one not noticed previously.

After about an hour, since the hydrophones no longer detect sound sources, Commander Gran decides to return to periscope depth; this was done at 4.30 AM. Sailing in silent mode, and at periscope level, a destroyer was sighted stationary on a bearing of about ten degrees to the left, with a beta close to zero. Fearing that this unit would detect them and hunt them, the crew of the Aradam returned to the seabed for another hour.

At 5:52 AM, as the hydrophones still did not detect any noise, the boat returned to the surface to transmit the discovery signal. After about ten minutes – it was by then dawn – the destroyer was sighted again, as it appeared motionless and indeed immobilized. Although confused by the unit’s lack of reaction, Gran decides to return once again to lie on the seabed, this time until 7.30 AM, when he decides to return to periscope depth to examine the situation more carefully.

Proceeding at minimum revs, so as to be able to steer without producing too conspicuous a wake with the periscope, the Aradam once again sighted the stern of the destroyer, which stood out against the coast of Kelibia, and saw clouds of black smoke rising from its bow. It was assumed that the destroyer had tried to run the coast in an attempt to save itself. The hydrophone, however, picks up noises “of considerable importance”, causing it to return once again to the bottom.

The Aradam remained in the area throughout the the 6th, so to make sure that the destroyer was sunk.

April 7th, 1942

At dawn the Aradam sighted a tugboat near the stranded destroyer and decided to return once more to the seabed to await new developments. In the evening, a radio message was received from Rome confirming the presence of a destroyer that had run aground and been set on fire and the accuracy of Gran’s previous estimations.

A few days later, the Maritime Military Command of Pantelleria sent a squadron of MAS to the site to ascertain the condition of the destroyer, which continues to emit abundant smoke; the ship, which was broken in two and half-sunk in shallow water, would be identified by the call sign painted on the bulwark, H 43, as the British destroyer H.M.S. Havock.

Based on this, in the report on the incident Maricosom assessed that the Havock was torpedoed by the Aradam. This will be the version delivered to Italian historiography. For example, Giorgio Giorgerini wrote in his book “Men on the Bottom”: “The Aradam had hit the enemy destroyer from a distance of 500 meters, immobilizing it. The Havock, coming from Malta and bound for Gibraltar, tried to save itself by trying to put back into operation at least part of its engine to try to run aground on the coast, but was prevented by the violent fire that broke out on board. Shortly thereafter, the British ship blew up and sank, broken into two pieces.”

According to some sources, after the launch, the Aradam surfaced, observing the enemy unit immobilized on the coast near Ras el Mirk, with a fire on board. Running aground on the coast, H.M.S. Havock would soon be broken in two by the explosion of the ammunition depots, observed from aboard the submarine (however, there seems to be no mention of this explosion in the description of the action of Commander Gran).

Quite different is the version given by British sources, according to which H.M.S. Havock ran aground due to a navigational error, without any involvement of the Aradam. The destroyer, under the command of Lieutenant Commander Geoffrey Robert Gordon Watkins, had been damaged a few days earlier during the Second Battle of Sirte (by the fire of the battleship Littorio, which had damaged a boiler, with eight casualties among the crew) and then further damaged by an air attack on Malta on April 3rd, during a first attempt to repair the damage in a dry dock in Valletta. It had left the island on the evening of April 5th bound for Gibraltar, with one hundred British soldiers on board who were due to leave Malta.

Before leaving Malta, Commander Watkins had been advised to scan the seabed when approaching the Kelibia lighthouse (the crossing of Tunisian waters would necessarily take place at night), and pay attention to the shallow waters to the north of the lighthouse and the shoals off Ras el Mir and Cape Bon, and to keep no more than two miles from the coast in order to avoid the minefields located further east.

He would have to decide for himself how fast he would have to keep and adjust so that he would be as far west as possible by dawn. While crossing the area, Watkins could have encountered enemy motor torpedo boats and minesweepers, as well as Axis convoys bound for Libya. Watkins had decided to round Cape Bon at a speed of 30 knots (both to be as far west as possible by dawn, and to minimize the chances of sighting in case he encountered an enemy naval force in the channel), and to keep the armament ready in case of an encounter with Italian or German motor torpedo boats.

Arriving in sight of the Tunisian coast, H.M.S. Havock had moved to pass about a mile and a half from the lighthouse of Kelibia, about ten degrees from the shore. The night was clear, moonless and with fog banks on the coast, and Watkins – who had taken over command of the voyage shortly before – had been informed by the navigation officer Lack that the ship was proceeding slightly further ashore than planned, but that this would not be a problem.

In rounding the lighthouse of Kelibia, H.M.S. Havock had made four approaches; Watkins had repeatedly asked Lack if the ship was on a safe course, each time receiving an answer that it was “a little” shifted toward land, but still safe. At 3.50 AM Watkins, who had remained on the bridge because the last segment of the course traced by Lack to round Cape Kelibia had seemed strange to him, had sighted what seemed to be a whitish wave towards the bow and had pulled a little out, and then ordered the engines to be put all the way back and the rudder all the way to starboard.

However, it was already too late: at 3:58 AM H.M.S. Havock had run aground at thirty knots on a sandbank three hundred meters from the coast, near Kelibia (more precisely, on the beach of Hammam Ghezzaz, in a position variously reported as 36°52’23.1″ N and 11°08’171″ E or 36°52′18″ N and 11°8′24″ E or 36.87167° N and 11.14° E), in depths of about five meters.

A sump in the main steam pipe had burst, killing one man, and severely burning five others, one of whom would later die in hospital. After a vain attempt to lighten the ship by throwing ammunitions overboard, the captain concluded that the H.M.S. Havock was lost and gave orders to the crew and passing personnel to land on the nearby coast, also starting preparations to self-destruct the ship. The plan was to sprinkled the ship with fuel and cordite, and after all the crew had been disembarked (in the meantime it was dawn), ignited the cordite. A depth charge placed in the sonar room was detonated, tearing the bow apart and reducing H.M.S. Havock to an unserviceable wreck. Prior to the self-destruct, at 4:15 AM, Watkins had reported that the ship had run aground 2.5 miles by 20° from the Kelibia lighthouse (in position 36°48′ N and 11°08′ E, or by another source 36°52′ N and 11°08′ E), that he could not disentangle it and was preparing for scuttling.

David Goodey and Richard Osborne, authors of a monograph on the history of the Havock (“Destroyer at War: The Fighting Life and Loss of HMS Havock from the Atlantic to the Mediterranean 1939-1942”), compare the official Italian and British versions, emphasizing the times indicated by both sides. According to the British, when the H.M.S. Havock ran aground, the engine room clock, which followed the Maltese time zone (Malta Standard Time), stopped at 3:58 AM. This was when the ship hit the shoal while proceeding at thirty knots. The Aradam supposedly followed the Central European time zone; if the two units were in the same time zone, the Aradam probably sighted H.M.S. Havock as it proceeded along the coast and fired a torpedo at it, missing it.

Alternatively, the Aradam sighted H.M.S. Havock when it was already stranded and the torpedo exploded against the seabed (due to the shallowness) or missed the target, as it was immobilized while Commander Gran had calculated the launch data for a moving unit. The description of the attack according to Italian sources – H.M.S. Havock hit at 3.17 AM by a torpedo, run aground and then broken in two by the explosion of the ammunition depots, caused by a fire triggered by the torpedo – is incompatible with what was reported by the survivors, according to whom the ship was not hit by torpedoes at the time of the grounding nor did there be any explosion until two o’clock the following afternoon, when the crew of H.M.S. Havock, already under guard by the French and out of sight of the wreck, heard a violent explosion and saw a column of smoke hundreds of meters high, and which Watkins attributed to depth charges and/or the aft ammunition depot, probably reached by the fires that were still raging on board (and which throughout the day caused several minor explosions of reserves and other ammunition).

In reality, the controversial mention of explosions on the wreck of H.M.S. Havock seems to be the result of the retrospective reworking of the attack made by secondary sources, while in the original account it is said, on the contrary, that no explosion was heard, so much so that Commander Gran remained for several hours in the impression that the destroyer was still able to counterattack, which would have been impossible if it had been torpedoed.

The Italian (original) and British versions do not seem to be in contrast: the most logical explanation is that the Aradam launched the torpedo against H.M.S. Havock, missed it, and while the submarine disengaged and lay on the seabed, the destroyer ran aground due to a navigational error, without realizing that it had been attacked. By the time the Aradam returned to periscope depth – only for brief moments, hours apart – the destroyer had already been abandoned and set on fire by the crew, and this spectacle led to the erroneous belief that it had been torpedoed.

Other versions reported by secondary Italian sources state that H.M.S. Havock was torpedoed by the Aradam and tried to run aground, but was broken in two by the explosion of the ammunition depots; or that it would run aground on its own and be torpedoed and destroyed by the Aradam after it ran aground; or that it would have run aground in an attempt to avoid the torpedo of the Aradam, then being scuttled by the crew once it was established that it was impossible to disentangle it. None of these versions, however, is confirmed by Commander Watkins’ report or by the survivors’ accounts.

The wreck of H.M.S. Havock in a picture taken by an Italian airplane on April 11th, 1942

(From “In Passage Perilous” by Vincent O’Hara)

According to what was noted at the time in the diary of the operations division of the General Staff of the Kriegsmarine, “according to the claims of the British prisoners [of the Havock], the destroyer ran aground and was blown up by its crew after an Italian submarine attacked it unsuccessfully.”

The crew of the Havock, camped on the coast near the wreck, surrendered to the local authorities (loyal to Vichy France) and was first taken to the Coast Guard barracks in the nearby town of Kelibia, and then interned in the concentration camp of Laghouat, in Algeria, where the British were in fact treated, rather than as military belligerents interned by a neutral country (which Vichy France claimed to be), as prisoners of war in an enemy country; they were kept by the French in worse living conditions than those of the British prisoners in Italy and Germany until November 1942, when they were liberated following the Anglo-American landings in French North Africa (Operation “Torch”) and the passage to the Allied cause of the Vichy troops stationed there.

On the night between April 7th and 8th, 1942 the wreck of H.M.S. Havock was boarded by the Italian tugboat Instancabile and inspected by Italian soldiers under the command of Liutenant Commander Ernesto Forza, who seized secret documents that remained on board (this too, however, is in contrast with what was stated by Commander Watkins, according to whom all secret documents would have been destroyed by fire before abandoning ship, destruction extended even to devices such as sonar and direction finders and torpedoes which were launched towards the open sea to prevent parts from being found). This, evidently, was the tugboat observed by the Aradam near the wreck of the Havock.

The news of the sinking of the Havock was announced by the Italian Supreme Command in the war bulletin no. 675 of April 7th 1942 (“… Our naval vessels set fire to and sank the British destroyer Havok”) and then further specified in bulletin no. 691 of 23 April (“Further investigations have made it possible to establish that the British destroyer Havock referred to in bulletin no. 675 was torpedoed and sunk by our submarine Aradam under the command of Lieutenant Oscar Gran returning from a cruise“).

Commander Gran would be decorated with the Bronze Medal for Military Valor (“Commander of a submarine, on a war mission in the Mediterranean, he attacked and torpedoed an enemy destroyer with serene courage and skill, demonstrating that he possesses high fighting spirit and fine military qualities“), and his second, Second Lieutenant Edoardo Burattini, with the War Cross for Military Valor (“Second Officer of a submarine, it ensured the combat efficiency of the unit and assisted the commander with serene courage and daring in the attack and torpedoing of an enemy destroyer“).

April 14th, 1942

Since an Italian convoy was expected to pass through the area escorted by the torpedo boat Lince and the destroyer Premuda, the Aradam reduced its activity in order to avoid accidents.

April 15th, 1942

Strong noises on the hydrophones were detected, but they are attributed to the transit of a French convoy reported from Rome and which according to estimates should pass right off Kelibia.

April 18th, 1942

Despite rough seas and reduced visibility, the Aradam sighted a ship, but shortly thereafter also noticed a CANT Z. 506 seaplane on its vertical, indicating that it was an Axis ship to which the seaplane provided air escort.

April 19th, 1942

The crew sighted off Cape Bon an Italian steamer, the Nino Claudio, heading north.

April 20th, 1942

Visibility worsens even more, so much so that it was more profitable to stay at periscope depth to carry out hydrophones listening. Indeed, sound of propellers was picked up and the submarine emerges to try to spot the ship or ships in question; however, it was impossible to distinguish both the number and the type of ships detected on the hydrophones, and since the passage in the area of an Italian convoy (tanker Panuco and two torpedo boats) had been reported, Commander Gran preferred not to approach, thus avoiding incidents of friendly fire.

At 10:24 PM, the Aradam received an order to return to base, which was transmitted at 6:10 PM (“No. 162173 – Smg Aradam – zone A – Smg Micca fictitious. Maricosom – I cancel my previous communications (STOP) Leave ambush immediately by returning to Cagliari (STOP) Reverse return routes the outward one»). During the mission, the Aradam had received 45 telegrams from Supermarina regarding the possible presence of other targets in the area.

May 1942

The Aradam was sent on patrol north of Cape Blanc.

June 11th, 1942

The Aradam was sent, along with four other submarines (Ascianghi, Onice, Corallo and Dessiè), to lie in ambush first near Cape Blanc and then west of Malta (in the triangle between Malta, Pantelleria and Lampedusa).

September 4th, 1942

Lieutenant Gran relinquished command of the Aradam, being replaced by the 35-year-old Alpinolo Cinti, from Ripatransone.

October 20th, 1942

Lieutenant Cinti relinquished command of the Aradam and was replaced by Carlo Forni, 34, from Genoa.

November 7th, 1942

Following the sighting of large Anglo-American naval forces sailing from Gibraltar to the west (it is the invasion fleet of Operation “Torch”, the Allied landing in French North Africa, but Supermarina – while believing that a landing in North Africa is the most likely hypothesis – does not exclude the possibility that it is a convoy bound for Malta), the Aradam was sent to patrol the Gulf of Philippeville, in the waters of Algeria, together with numerous other Italian submarines (Acciaio, Argento, Asteria, Brin, Dandolo, Emo, Galatea, Mocenigo, Porfido, Platino and Velella). In total, Maricosom – on the basis of an order from Supermarina, transmitted at 10.06 PM on November 6th – sent 21 submarines to the western and central-western Mediterranean, to counter the enemy operation: 12 submarines of the VII Grupsom (including the Aradam) were deployed west of the island of La Galite (zone “A”), 7 submarines of the VIII Grupsom were sent off Bizerte (zone “B”), and 2 others in an advanced position between Algeria and the Balearic Islands.

The directive was to ‘widen the waters allocated to the ambush of submarines … to give them more freedom of action in the areas themselves.” These positions turned out to be too far from the actual landing zones (Oran and Algiers), but they were not modified, because the Germans mistakenly believed that the Allies could attempt further landings in Tunisia as well (in which case the Italian submarines would be in an ideal position).

At 03:31 PM Maricosom (the Submarine Squadron Command) informed all submarines patrolling in the western Mediterranean of the position of a British naval squadron and an enemy convoy, reported at 10:40 AM. At 08:07 PM, the Submarine Squadron Command reported the position of two convoys sighted on two separate occasions, both heading east and consisting of merchant ships escorted by battleships, aircraft carriers, cruisers and escort ships.

November 8th, 1942

The landings began: 500 Anglo-American transport ships, escorted by 350 warships of all kinds, land a total of 107,000 soldiers on the coasts of Algeria and Morocco. Since these operations take place in the areas of Algiers and Oran, the Italian submarines are too far east to intervene; since the Germans believed that the Allies could make further landings further east, towards Tunisia, it was initially decided to leave the submarines where they were.

November 9th, 1942

At 07:09 PM the command of the Italian submarine fleet, Maricosom, reported to all boats at sea that enemy steamers are moving eastwards, and that landings are taking place at Bona and Philippeville; It therefore gives the order to attack any merchant or military ship leaving these ports, but avoids (in order not to risk incidents of “friendly fire” with other units sent to the area) attacking submarines, MAS and motor torpedo boats.

November 13th, 1942

Informed of the landing of British troops at Bona and Philippeville, Supermarina ordered the submarines at 06:38 PM to enter these harbors, attack with the utmost determination, and then return to their respective patrol sectors at dawn. In particular, Aradam, Emo, Granito and Volframio were sent to the bay of Bona, while Argento, Ascianghi, Asteria, Mocenigo and Velella were sent to that of Philippeville. None of the boats, however, were successful: many did not spot any ships, the others were unable to attack them due to the unfavorable sighting conditions and the strict enemy vigilance.

November 14th, 1942

At 06:02 PM Maricosom arranged a new offensive in the harbor of Philippeville: Aradam, Granito, Emo and Volframio received orders to carry out an offensive search during the night, acting with the utmost decisiveness, then returning to their respective patrol sectors. However, this second raid was also fruitless.

November 16th, 1942

Under the command of Lieutenant Carlo Forni, the Aradam penetrates the bay of Bona at night for an offensive reconnaissance; having sighted a convoy heading towards Bona (for another source, to the west) made up of three merchant ships, with a large escort of light units (according to another source it would have sighted an isolated ship, with a 210° course), it approached on the surface with the favor of repeated showers and launches two pairs of torpedoes against a merchant ship of 2500 GRT, the first at 3:58 AM and the second at 5:06 AM, from close range (500 meters, in both cases).

All weapons missed their targets. Due to the counter-maneuvers of the attacked ships; having now reached waters too shallow to attempt a new attack with torpedoes, at 5.14 AM the Aradam attacked the nearest merchant ship, which was heading towards the coast, with its deck gun, believing that it had damaged it slightly (the third shot fired seems to hit between the bridge and the funnel. According to another source, it would have scored several shots. At 5:44 AM, however, a shot exploded prematurely outside the muzzle of the gun, dazzling the gunners, and forcing them to cease firing. At this point, being only three miles southeast of the entrance to the port of Bona, Forni gave up the chase due to the reduced availability of electricity and the shallow waters. The Aradam was already crawling on the bottom, and continuing like this it would end up running aground. Forni then disengages towards the open sea, diving. (According to another source, after shelling and hitting the steamer, he disengaged by diving due to the quick reaction of the escort.)

According to Giorgio Giorgerini, however, this attack would have taken place in the harbor of Bougie, while the strong enemy anti-submarine surveillance would have prevented the Aradam from penetrating the bay of Bona. According to a different version, this action took place in the bay of Bona, and then the Aradam tried to force this bay again, but failed due to enemy surveillance.

The convoy attacked was probably ET. 1, consisting of five ships, sailed from Algiers on February 18th and it arrived in Gibraltar on November 20th. Alternatively, but less likely, it is possible that it was TE. 3, made up of about fifteen units, which left Gibraltar on November 11th and arrived in Bona on November 17th.

The Supreme Command will give news of this action in the war bulletin no. 906 of November 17th: “One of our submarines under the command of Lieutenant Carlo Forni, forced the entrance into the roadstead of Bona and seriously damaged a large enemy merchant ship with cannon fire“.

November 20th, 1942

At 8.30 PM the British submarine P 228 (later H.M.S. Splendid, Lieutenant Ian Lachlan Mackay McGeogh) detected diesel engines noise from the southwest and after a few minutes, having begun the attack maneuver against what it correctly assumes to be a submarine, it notices that it is sight onto the left there was an approaching submarine, which is identified as Italian.

At 08.40 PM, in position 40°38′ N and 13°48′ E (off Naples), P 228 launched a salvo of six torpedoes from the bow tubes; Non hits, two of the weapons explode at the end of the run after twelve minutes. McGeogh would conclude that he had missed the target by underestimating its speed. The submarine attacked was most likely the Aradam, which did not notice the attack.

December 1942

The boat was sent for an unsuccessful ambush in the waters of Cyrenaica.

January 1943

The boat was sent for another ambush off the coast of Cyrenaica.

February 1943

The boat was sent for another ambush in the waters of Cyrenaica (Gulf of Sirte).

March 1943

The boat was sent for ambush in the Gulf of Sirte.

April 10, 1943

The Aradam was in La Maddalena when, starting at 2.37 PM, the Sardinian base was subjected to a heavy bombardment by 84 Boeing B-17 “Flying Fortress” bombers of the USAAF. Immediately after the bombing, the Aradam was transferred to Bonifacio, to save it from any new air attacks.

April 1943

An inspection estimated the state of efficiency of the Aradam as “good” but highlighted the poor condition of the horns. Even more curious is the judgment expressed about the state of the crew: “regular”.

May 1943

The boat was sent for a patrol to the west of Sardinia.

Summer 1943

The Aradam entered the shipyard in Genoa to be transformed into a “carrier” submarine ” of slow-moving torpedoes (SLC), with the installation on deck of the special cylindrical containers for the transport of these assault vessels. Supermarina intended intensifying the operations of assault craft against the Anglo-American ships, and to this end increased the number of “carrier” submarines both with the conversion of existing units (the Aradam), and by adapting submarines under construction (such as the three new Murena, Grongo and Sparide of the Tritone class).

Epilogue

At the time of armistice between Italy and the Allies, on September 8th, 1943, the Aradam was caught in Genoa, (still under the command of Lieutenant Carlo Forni, but according to another source at the time of the armistice it would have been momentarily under the command of Lieutenant Mario Tromba) undergoing overhaul and maintenance work as well as the conversion into a “carrier” of slow-moving torpedoes.

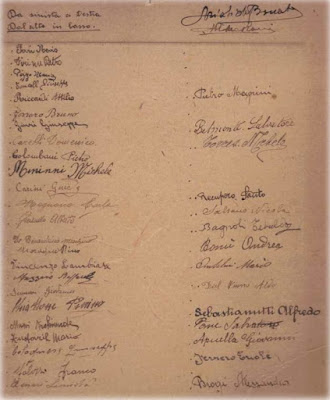

Unable to sail, the Aradam was scuttled by its crew on September 9th, to prevent it from falling intact into German hands. The crew of the Aradam dispersed; the twenty-three-year-old sailor Gregorio Barone, after the sinking of the submarine, managed to leave Genoa and cross the peninsula which had plunged into chaos, reaching his home in Torre del Greco where he remained hidden to escape the roundups during the brief German occupation of the city. When the Allies arrived, he returned to civilian life by opening a newsstand.

The Germans resurfaced the Aradam, after which there is information that is not entirely agreed upon regarding the details of its demise. According to most sources, including the book “Attack from the Sea” by Giorgio Giorgerini, the Germans gave it to the X Flotilla MAS of Junio Valerio Borghese, loyal to them, so that they could repair it and use it as an approaching unit for assault units; in December 1943, in fact, the X MAS had reconstituted the SSB operational group, equipped with the new San Bartolomeo torpedoes, built in the workshops of the same X MAS and evolution of the Slow Running torpedoes successfully used in the raids against Alexandria, Algiers and Gibraltar between 1940 and 1943.

The submarine, already equipped with the appropriate cylinders for the transport of SLC and SSB, was placed in dry dock for repairs, and the “Aradam” assault vehicle transport group was established in Genoa (under the X MAS Underwater Assault Vehicles Department) intended to provide the crew and the necessary support. Lieutenant Carlo Forni, his old pre-armistice commander, who had in the meantime joined the Italian Social Republic, was appointed to its command.

According to “Italian Ships and Sailors in the Second World War” by Erminio Bagnasco, however, after scuttling, the Aradam was recovered by the National Republican Navy, the small Navy of the Italian Social Republic, of which theoretically the X MAS was part but which in reality constituted a force clearly distinct from it and indeed rival, since Borghese answered directly to the Germans and there was no good blood between him and the leaders of the M.N.R.

On August 18th, 1944, while the Aradam was being refitted, the Germans seized it “by force”, an episode that Bagnasco gives as an example of the difficult relations existing between the M.N.R. and the Germans, studded with “accidents” of considerable gravity, very different from those that ran between the Germans and the X MAS.

In any case, the refitting work never came to an end, because on September 4th, 1944 the Aradam, still under refit, was sunk in Genoa by an American air raid.

A different version is the one contained in the book “The Black Prince” by Alessandro Massignani and Jack Greene, according to which the X MAS would have put the Aradam back into service by January 1944; But a mistake seems likely.

The date of the sinking is also incorrect, given as September 1st, 1944, instead of 4 September. Massignani and Greene also speculate that the bombing would not have been accidental, and that “the Regia Marina del Sud was well informed that the Aradam was ready with containers to carry the ‘pigs’ beyond the Allied lines.” A website dedicated to the X MAS also states that in January 1944 the Aradam “was able to carry out sea trials and go into action”, however there is no record of any mission carried out by this unit from January to September 1944; another, apparently referring to a book by Sergio Nesi, states that the Aradam was put back into service and began sea trials at the beginning of January 1944, but was sunk in September before it could operate.

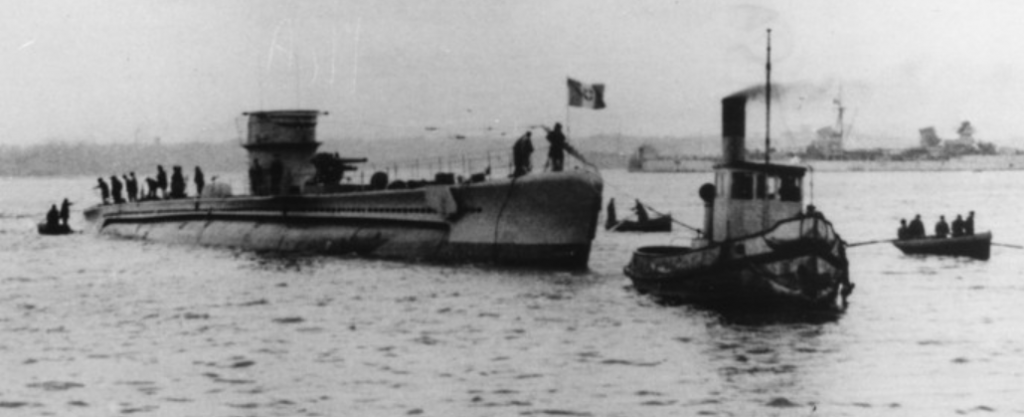

The wreck of the Aradam in Genoa.

(From the Magazine Storia Militare)

Sub-chief Giovanni Croce, 22 years old, from Piove di Sacco, part of the crew of the Aradam, was killed in the bombing. Another member of the crew, the sailor Salvatore Frega, died on 2 December 1944 in the Santa Tecla sanatorium in Genoa, from an illness contracted in service.

The sinking of the Aradam also led to the disbandment of the X MAS Assault Vehicle Transport Group. The wreck of the submarine was recovered in March 1947, just a few days after its formal removal from the roster of the now no longer Royal Navy, which took place on February 27th of the same year. It was then demolished by the Bartoli and Cavalletti company of Savona.

Original Italian text by Lorenzo Colombo adapted and translated by Cristiano D’Adamo

Operational Records

| Type | Patrols (Med.) | Patrols (Other) | NM Surface | NM Sub. | Days at Sea | NM/Day | Average Speed |

| Submarine – Coastal | 50 | | 26,144 | 3,223 | 280 | 104.88 | 4.37 |