On May 22nd, 1939, the Kingdom of Italy and the German Reich signed a new military pact (Pact of Steel) that linked the future of the two nations. Following the signing of the pact, and as part of the negotiations, the Italian high naval command met with their German counterparts in Friedrichshaffen (Germany) on the 20th and 21st of June, 1939 to discuss the terms of naval collaboration.

This alliance was quite strange in nature, and it can be seen as the result of the most unusual historical development of the European geopolitical scenario following the conclusion of World War I. As the first few months of co-belligerence demonstrated, the alliance between Italy and Germany was mostly political and economical, while military collaboration was minimal. German political and economical supremacy would inevitably be reflected in military affairs, and therefore the Italian government was well intended to maintain a parallel course with the Germans, avoiding direct military collaboration. The two allies were not equal; Germany had an impressive industrial apparatus which, even during the war, increased production, while Italy, a country mostly agricultural, had a limited industrial capacity and a chronic shortage of prime goods.

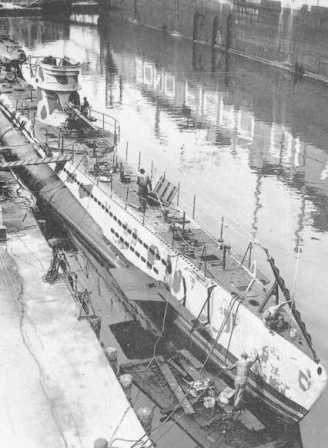

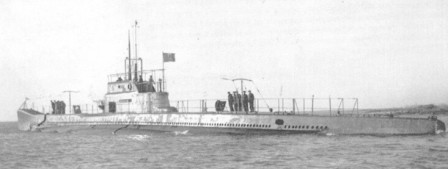

Italian submarines in Bordeaux.

(Photo U.S.M.M.)

The Friedrichshaffen meeting did not generate much momentum; Germany failed to transfer radar technology to her new ally, while Italy limited her exchange to selling advanced thermal torpedoes to the Germans. Naturally, very soon it would be the Germans selling advanced electric torpedoes to Italy along with any technologically essential equipment. During these meetings, Admiral Cavagnari, the Italian equivalent of the First Sea Lord, committed to an Italian presence in the Atlantic. For a navy, which had been specifically built for a strictly Mediterranean war, this commitment was a stretch. Still, Italy had built high displacement submarines capable of crossing the Strait of Gibraltar, reaching the Atlantic for long patrols, and then returning home. During the 1939 discussions, the glamorous successes of German U-Boot during World War I were still vivid in the minds of all naval strategists. Italy, which during World War I had mostly fought in the Adriatic, not only had expanded her range of action to the Mediterranean basin, but was also considering operating in both the Atlantic and Indian Oceans.

With the Italian expansion in East Africa, despite the limited docking facilities, one would have expected a forceful Italian presence in the Indian Ocean and Red Sea to impede British maritime traffic. Unfortunately, due to poor planning, defective equipment and waning supplies, the fear of an Italian menace in the area failed to materialize. Later, Italian submarines will, once again, appear in the Indian Ocean, but this time originating their journeys from the Atlantic coast of France.

On the Atlantic side, and especially in 1939, no one expected the availability of docking facilities. Spanish support, although much sought after, never materialized and therefore there weren’t any other friendly harbors available. Italian and German submarines would have had to sail from their home bases, thus allowing only for very limited patrols. The Italians had to deal with the Strait of Gibraltar and the local British presence, which, despite Spanish pro-axis tendencies, still gave the Royal Navy a dominant control over the narrow passage. Nevertheless, Italian submarines would cross the strait numerous times without any major incident.

With the unexpectedly rapid fall of France, the Germans suddenly gained access to the Atlantic and its many ports. Although the U-boot fleet was at this time very limited in number, its technical advantages were enormous. Germany would immediately begin an unprecedented building program which would soon dwarf the Italian submarine fleet, at the time the second largest in the world. In accordance with the agreement reached a year earlier, in 1939, immediately after Italy’s entry into the war, the German naval command requested an Italian presence in the Atlantic. As originally agreed, the Italian vessels would patrol the area south of Lisbon, while the German would patrol the area north of the Portuguese capital. The division would have avoided complicated coordination between the two navies, and would have also favored the Italian vessels in terms of climatic conditions.

An Italian military commission visited various French ports along the Atlantic coast and, after easy negotiations with the Germans, the choice fell on the inland port of Bordeaux. This was an unusual selection, but it proved to be an excellent one. Bordeaux is almost 50 miles from the Bay of Biscay to which it is connected by the river Gironde. The same river is also connected to a sophisticated system of navigable canals, which connects it to the Mediterranean. Bordeaux had good docking facilities, including dry docks, repair shops, and storage depot. All these facilities were in a state of abandon, but unscathed by war and easy to restore to service.

(Photo U.S.M.M.)

Like all Italian military bases, the one in Bordeaux needed a telegraphic address. At the time, telegraphs (and teletype) were the primary means of communication. The name chosen was a simple one: B for Bordeaux and SOM as an abbreviation for “Sommergibile,” submarine in Italian. In the Italian military world, the letter B was called “Beta”, just like our “Bravo”; the combination of the two created the name BETASOM. This name would enter the history books to signify a lesser known, but very important page of submarine warfare. All communications from BETASOM were routed by the Germans via Paris or Berlin. There was no direct line from the base to Rome. To establish direct communications, the Italians installed several powerful radio apparatuses aboard the liner De Grass.

The French liner De Grass.

(Photo U.S.M.M.)

The Italian submarine base occupied a constant level basin connected to the river Garonna by two lock gates. The basin included two dry docks, one large enough for the ocean going boats, and a second one capable of servicing two smaller submarines at once. To the right of the lock gate pumping station sat the cafeteria and quarters for the troops belonging to the San Marco battalion. Immediately after, also on the right side of the basin, lay the two dry docks and behind them the repair shops and depots. The basin was shaped almost like a T .

The base was officially opened on August 30th, 1940 with the arrival of Admiral Perona. Other offices included the Chief of Staff C.F. Aldo Cocchia, (Capo di Stato Maggiore), the base commander C.F. Teodorico Capone (Comandante della Base), the officer responsible for all communications C.C. Bruno de Moratti (Capo Servizio Communicazioni), the officer responsible for all operations C.C. Ugo Giudice, and several other officers. The Germans assigned two liners to the Italians, the French De Grass (18,435 tons) and later in October the German Usaramo (7,775 tons).

A view of the” bassin”

(Photo U.S.M.M.)

The De Grasse, in addition to the already mentioned radio station, was used as a military infirmary, while personnel with serious conditions was sent to the local French hospital. The De Grasse was moored only a few hundred yards from the basin near the transatlantic passenger station. This large concrete building was quickly turned into barracks capable of hosting about 750 sailors. Nearby buildings were used for office space, storage, and other uses. The entire area was fenced and patrolled internally by 225 soldiers of the San Marco battalion and externally by German troops. The Germans, who had installed six 88 mm guns and forty-five 20 mm machine guns, provided for antiaircraft defenses. The Germans also provided for all antiaircraft detection services, and patrols along the Gironde and the Bay of Biscay.

The basin was capable of hosting up to thirty submarines. Each dock was equipped with the necessary infrastructure to provide vessels with fresh water, compressed air and electricity. Power to the base was provided by generators brought on purpose from Italy and by the local grid. The local repair shops did not have the equipment and machinery necessary for precision work aboard submarines, and much was shipped from Italy, along with 70 specialized technicians.

Later, the base began utilizing French personnel, but it always limited access to the vessel only to Italian workers. Despite the fear of sabotage, the relationship with the local work force was overall very positive. Despite the miserable living conditions and the German occupation, the base did not experience any act of violence or sabotage.

An aerial picture of the facilities in Bordeaux, France.

(Photo U.S.M.M.)

Since, as we have already mentioned, the base of Bordeaux was quite far from the ocean, the Italian command set up a smaller base in La Pallice, near La Rochelle on the Bay of Biscay, about 50 miles north of the estuary of the river Gironde. It was equipped with a dry dock and a few temporary accommodations for up to three submarine crews, and was utilized only for smaller repairs and tuning. The base in Bordeaux, since it is a fluvial port, did not have the facilities to test submarines underwater. This testing was done in the Bay of Biscay, but a return trip along the 50 miles from the ocean to Bordeaux would have caused the loss of much time. Naturally, the work performed in Palluce was usually simple. This base was also used as the last stop before leaving for a mission and as the first one upon returning.

The fifty miles from the ocean to Bordeaux were quite treacherous. A local French pilot was always employed in bringing the units safely up and down the river. Since the Gironde has a noticeable tidal excursion, admittance to the basin was allowed only during high tide (twice a day). Also, navigation along the river was much safer during high tide, even though the navigable channel was clearly marked and the river often dragged. Considering that submarines have a very shallow drought, tidal excursions were never a factor, despite the fact that in this area they average 18 feet.

After the creation of the Italian base, several French ports were the targets of heavy aerial bombardment. Eventually, on October 16th and 17th, even Bordeaux became victim of these British attacks. Admiral Perona, responsible for the over 1,600 personnel at the base, decided to spread out some of the personnel. This decision was reinforced by a new British bombardment which took place on the 8th and 9th of December. This time, over 40 planes dropped a large number of bombs and mines. Damage to the Italian base was limited, but shrapnel hit the De Grass while the Usaramo was sunk.

Several essential services were dispersed in a range of about 9 miles from the base. The ship Jaqueline, used as an ammunition depot, was moored further away from the base, while part of the torpedo ordnance was transferred to Pierroton. The De Grasse was vacated and moved further away from the base. Headquarters were relocated to Villa Moulin d’Ormon, while officer quarters were rearranged in the castles of Robat and Tauzien. The remaining personnel were housed in a summer camp in Gradignan.

The base would remain fully operational until September 8th, 1943 when, after the Italian armistice, it was occupied by the Germans. Thereafter, some Italian personnel opted to continue fighting alongside the Germans, but Italian command was never re-established. It should be noted that while the Germans built concrete pens for their boats in Bordeaux, the Italian submarines where always exposed to aerial attacks. Despite this weakness, not a single vessel was lost in port or along the Gironde to aerial attacks.