Mr. Romano, I would like to thank you for having given us the opportunity to interview you. As we already mentioned, we are interested in the period 1940-1943.

Before answering your question, I must make a preliminary remark. I know that you see, with great diligence and depth, the events of the “Regia Marina” during World War II in the period 1940 to 1943. Allow me to remind you that for the “Regia Marina” the war did not end on September 8th, 1943 but continued on until April 25th, 1945. For some of us, it went on until 1946, when we were no longer “Regia”, but continued our small war clearing the seas of mines of any kind to reopen them to free navigation.

This last war was not one “en masse”, but I assure you that given the dangers of the underwater weapons spread out and the technical characteristics of the equipment used to neutralize them, this was also considered a war and recognized as such to all effects

Do you remember where you were the day war was declared? (June 10th, 1940)

I perfectly remember what happened on June 10th, 1940. I was an ‘avanguardista’ (a rank within the youth movement of the Fascist Party), musketeer, actually I was a cadet. I had the highest rank an “avanguardista” (from vanguard) could reach. My responsibilities were simple, for instance: in case of “general assembly” I would gather the largest possible number of “avanguardisti” and reach, running, Piazza Venezia. I underline on foot. For those who know Rome, running from Piazza Mazzini to Piazza Venezia is not a stroll!

Thus one might ask, “What was a general assembly?” Following a prolonged wailing of the sirens, all activist had to interrupt, wear their uniforms, and run to Piazza Venezia to listen to the Duce’s words. Then, we did not call him by his last name – Mussolini – but Duce, with the capital D. Not many general assemblies took place, as far as I remember three or four; indeed four. One on occasion of the levying of the sanctions against Italy (November 18th, 1935 if I am not mistaken), one for the conquest of Addis Ababa (May 5th, 1936), one for the proclamation of the empire (May 9th, 1936) and one for the declaration of war (June 10th, 1940). I was present at all of four general assemblies and “well” placed almost under the infamous balcony. This was because we made the journey really running, arriving at the place of the assembly before the square would become crowded by the “oceanic wave” of black shirts as seen on photographic documentation of the period.

On June 10th, 1940 it was the last time we heard the sirens in peacetime. Already the night of the 10th they went off for an aerial alarm. French airplanes flooded us with leaflets (which the following morning had disappeared by a miracle), and in the Piazza Mazzini neighborhood, where I used to live, fell an intense rain of shrapnel from our antiaircraft guns. This was my June 10th, 1940.

In an Italian movie recently released in the United States, that day was described as a moment of collective euphoria. Do you think that this description is exaggerated?

I haven’t seen the movie you mentioned, thus I cannot evaluate the level of euphoria described in the motion picture. One thing is sure, collective euphoria did exist in Piazza Venezia the afternoon of June 10th, 1940 and it is abundantly documented, but it does not count. In Piazza Venezia there were, in greater part, just us, very young schoolboys, the young Fascists (18 or older), the university students, the activists from the neighborhoods’ Fascist groups, and a large number of militia and black shirts from a great variety of social backgrounds and all relatively young.

Of course we were excited by the thought of war against the “hated plutocracies”, which would have inevitably concluded with our final victory as in Abyssinia (1935) and Spain (1938). “The word of the day is Victory… and we shall win!” (this is an exert from Mussolini’s speech) But outside Piazza Venezia everyone was shaking their heads with very strong doubts about the future. The most doubtful were those who had lived the affairs of the First World War. Reflections ranged from making sacrifices, to grief and destruction, to the realization that we were not ready to face a war, even though I believe that that day no one – because you are asking me about the collective euphoria of the 10th of June – had any ideas about what would actually happen.

Victories in Abyssinia and in Spain, and those of Hitler’s Germany, exalted to the highest by Fascist propaganda, inebriated and made us feel proud, and the idea of “breaking the enemy’s back” made us particularly euphoric. But, as early as the night of the 10th of June, the presence of enemy airplanes over the skies of Rome dimmed the enthusiasm of many, but not all, and numerous were the requests for voluntary draft or voluntary transfer to a war zone. Numerous draftees for every armed force were forcefully recalled, or kept in service, and the Italians, euphoric or not, answered the call, did their duties, faced great sacrifices than had previously been forecast. Everything considered, they did their best. If things have gone the way they have, we now know whose responsibility it was.

Probably during the first year of war you were still a student; what do you remember of the war bulletins or newsreels by LUCE. Was radio important?

I remained behind a school desk until May 31st, 1941 when with a stroke of pen the final exams were abolished and the school year closed with a regular assignment of term’s marks as if it were a regular class. My memories of the time? Every day at 1:00 PM the war bulletin, called “Official Communiqué”, was radiobroadcast in all classrooms and we listened while standing. Honestly, I must say that listening to “…one of our submarines did not return to the base”, we youths were not conscious of the military tragedy, and most of all the human one which was concealed behind those words. What we knew of the war was what the official communiqué said, and a few comments, always positive, which would appear in the newspapers, and also what was shown in the movie theaters, just before the movie (newsreels by LUCE). These last one, were always referring to events of a few weeks earlier and always covered successes of our armed forces. The radio, in addition to the communiqués of 1:00 PM and the news also at 1:00 PM and at 8:00 PM, broadcast only music of various genres, a few variety shows, a few plays and some operetta. All was rigorously broadcast live and usually from EIAR with offices on Via Asiago in Rome, or some other city (Turin, Milan, Naples, Palermo).

Now and then, taped music “…we broadcast reproduced music…” was also broadcast. At night there was a “short commentary of today’s events; Politicus speaking”. Right now I don’t remember which commentator was hiding behind this pseudonym, perhaps Mario Appelius, but the comments were always positive. There was absolutely no political debate. For the record, the identification signal exchanged by the various stations when they connected to the network was the chirping of a bird, different from station to station, and which inspired a famous song. But let’s return to the war bulletins, news in the papers, in a word diffusion of news about the progress of the war. I will not dwell on comments. Let me show you a clipping from the newspaper “La Stampa” of Turin dated April 1st, 1942, that is to say three days after the tragic night of Cape Matapan. In this clipping is reported bulletin number 297. Also, let me show you the radio program for April 2nd published by the “Corriere della Sera”.

Any reflection is up to you. Keep in mind that the first pages of the newspapers of the time were headlined in large print with the visit to Italy of the Japanese Foreign Minister Mr. Matsuoka. Nothing can be found about Matapan in addition to what I have already shown you. I would also like to remind you that in those days a radio was something that very few owned. The use of an external antenna was indispensable. In some lucky locations one could use, as an alternative, the box spring of a bed. Reception was not always good. Those owning a radio were easily identifiable.

Why am I saying this?

Because, for instance, Jews were not allowed to possess radios. They had them, but could not use them due to the noticeable outside antenna. Anyway, the most fortunate amongst the Italians had “powerful” radios (6 or 7 tubes) and could, even with the box spring, dial in secret into Radio London (the one with an identifying tune very similar to the beginning of Beethoven’s Fifth symphony) and receive some news from the other side. This news, naturally, was exaggerated to the opposite.

Why did you decide to enter the Naval Academy? Was this a decision dictated by a family tradition, or a voluntary choice?

My father was an officer (originally a non-commissioned one) from the signal station corps. He took part in World War I, fighting in the trenches with the San Marco battalion, and then had followed a career path with the signal corps. As a senior non-commissioned officer, he was the chief of station of some signaling posts and my mother and I, who were his family, followed him. In particular, at the Anzio station I spent my early years and my adolescence in daily contact with the signalmen group and the operational activities of the signal corps, which were essentially based on surveillance and optical and telegraphic communication. All this had surely left an imprint on me and with the years it transformed into a desire to enter the Navy through the main door, that is to say participate in the national competitive examination to be admitted to the Naval Academy. Therefore, my choice was fully my own and the only “suggestion” I received from my father was “study, study, study!”

Here I would like to remember that my father, after the period in the signal corps, participated as a volunteer in the Abyssinian War for about two years, and in 1939 in the Italian landing in Albania where, already an officer, he organized ex-novo the Albanian signal network. After a brief period in Rome at the Ministry of the Navy, in 1940 at the beginning of the war he returned, again as a volunteer, to Albania where he stayed until March 1943 when he was sent back home due to an illness contracted while in service and of which unfortunately he died.

But let’s go back to the “recommendations” of my father. I followed them to the letter since algebra, geometry, and trigonometry taught in high school were completely insufficient to pass the “killer” examination.

The announcement for the national competitive examination for the Naval Academy.

As soon as the national competitive examination was announced, I signed up. Actually, my parents did (I was 18 and legal age was 21), presenting a request for admission to the “preliminary training”. I passed the first medical in Naples, and a much more severe one in Leghorn. Finally, on July 9th, 1941 I crossed for the first time the gates of the Naval Academy, thus beginning my life in the Navy.

Training lasted about three months during which we conducted the same life as the cadets. We were taught again algebra, geometry, and trigonometry with daily lessons, tests, and oral exams. There was intense sport and sailor-like activity, and at the end, after a series of oral and written exams which were heavily weighted toward the evaluation of the “professional aptitude”, one would arrive at the yearned admission. It should be mentioned that, usually, despite the very large number of candidates, the placements available were not all filled. This is proof of the severity of the selection which did not take into consideration the strong need for young officers to replace the numerous casualties caused by the war.

Admission to the academy, about which I just spoke, was not for sure; one could always be dismissed, especially after the first year of attendance, for good reasons, suddenly, and without possibility of appeal.

During this period, cadets had to pay a monthly boarding fee, and an assessment fee for the equipment which was distributed during the three years of attendance, and a payback for eventual medicines, extracurricular material, and damages (even a broken plate). Furthermore, the cadet could go on short leave (twice a week) and the family had to contribute a small sum of money, which was used for the “purse” about which I will talk later. Age limits to enter the academy were quite restrictive. Nevertheless, there were a very limited number of seats available to non-commissioned officers with the necessary degree and with a maximum age of 25 years. Thus it happened that in my course were admitted two second chiefs, one of whom, the more advanced in age of the whole course, got the nickname “grandpa” (he was 25 and we were 18 or 19!), and “grandpa” he remained to us to the end of his days.

He was an important point of reference for all of us, a rock like those of the Dolomites from which he came. His wisdom, his calmness, were soothing moments to our boyish escapades, Yes, because amongst the austere walls, with the discipline, we were also 18-and-19 year-old boys. Grandpa had always been assigned to submarines. After a year of war he disembarked from, I believe, the Toti to be admitted with us to the academy. Forgive me this interlude not concerning your question, but going back to my past so many windows open and it is difficult to immediately close them all. Please, go on with your questions.

It is said that the academy was quite hard; long hours studying, much physical activity, and the unceasing desire to complete the courses to participate in the war. Are these mythologies or facts?

You asked me a question to which, due to the nature of the interview, I should give a short answer, but here again so many windows open up bringing back, reliving the years at the academy with the same intensity and participation with which I really lived them. Thus, I am afraid my answer will not be short. I shall not speak of the academy, but of “my” academy.

Behind the very elegant dress uniforms, the glowing red daggers with real mother of pearl hilts hid a life thought to be hard by those who had entered the academy with lesser convictions, but which instead was accepted, although with the inevitable whines, by those, like me, who had entered it with a strong desire to enjoy (in full breath) the most beautiful aspects and put up with a bit less enthusiasm, with the more rigid aspects. All is relative! The father of one of my course-mates, at the time a Vice-Admiral 1st Class who had entered the academy 40 years earlier, thought that “our” academy was not much different from a girls’ boarding school for young women from wealthy families.

My son, who entered the academy about 40 years after I did, thinks that my academy was comparable to living in the hard prison of the Cayenne (French Guiana). Throughout the years, the discipline and strictness applied in the academy have been proportioned with objective of transforming youths from a variety of social and scholastic backgrounds into men ready to consciously assume their responsibilities. One thing has never been absent from the academy in its 120 plus years of existence: inflexibility in regards to lack of loyalty and truthfulness. The disciplinary actions which derived and still derive are always the same: immediate termination. But let’s return to “my” academy.

Every day wake call at 0530 excluding Sundays when we were allowed another half hour of sleep. We slept in dorms for 60 cadets each.

0530-0600 Morning routine. Undo your bed, carefully folding sheets, blankets and pajama (making the bed was the “attendant’s” responsibility, characters those about whom I shall speak later on). Shaving was obligatory every day; no postponements allowed, not even for those who had not yet fully developed and had nothing to shave. During the morning routine, the non-commissioned officer on watch patrolled the dorms and he was the one to be asked for a medical check-up, or to call to report. “Mr…. called me to report for …..(in the Navy officers were always called by their last name preceded by “Signor”, or mister). I will give you more details later on.

0600-0630 Physical exercise in the courtyard.

Partial view of one of the “Studies”

0630-0725 study time, essentially dedicated to reviewing subject matters for the day’s lessons. The hardest part though was keeping the eyes open due to the strict watch by officers and non-commissioned officers who did not hesitate to call to report whoever was found “dozing off during study hours”. After all, getting used to fighting sleepiness was a not a subject matter but a hough thing to learn. Aboard, during the interminable sequences of four-and-four, meaning four hours of watch and four resting (so to speak), interrupted by alarms, action stations, cease action station, watch below, etc. one had to be used to keeping the eyes open and take advantage of the first five minutes available to catch up with a bit of sleep. But let’s return to my academy.

0725-0730 Brief break. All of five minutes!

0730 General assembly (in the courtyard) by section and lined up and then running to the mess for breakfast. The ritual into the mess was always the same; we entered running (a light run), we lined up at attention behind our chair (each table with about 10 cadets). “Hats off”, “sit down”. At the end of the meal “stand up”, “Hats on”, and lined up, running, we would leave the mess.

0745-0800 break. The cadets who had requested sick bay lined up and went to the infirmary for a medical check. Whoever had been called to report presented himself to the secretary of his class and waited to be called by the commander of his course to receive a good telling off, but not the disciplinary sanctions. These one would only be known at the general assembly at 1245, and I will describe it later.

During this break we also used the “patcher”, attendants who, with their toolbox, sat in the internal gallery for small patches, sewing (buttons, etc).

0800 Assembly, inspection of the uniform, hair, beard, and every other day physical exercise at the parallel bars the rope, or “battle station” at the brigantine interred in the courtyard, but identical to a real one for both sails and maneuvering.

“Action station” on the brigantine and the “rope”

0830 Beginning of the lessons. Each course was subdivided into sections of about 30 cadets and they carried on their activities, scholastic, athletic, and military, just like a regular high school class (in Italy a class is never separated and all students take the same courses). Class lasted 55 minutes. 5 minutes were needed to move from one classroom to another or from one building of the academy to another, always lined up and running. To us officers (deck officers) during the three years of a regular course were taught subject matters of the first two or three years of the faculty of engineering. In addition, subsidiary subject matters like trigonometry, visual navigation, astronomical navigation, gun ammunitions, naval guns, ballistics, explosive chemistry, underwater weaponry, naval architecture, thermodynamics, naval equipment, telecommunications, engine (machinery), equipment and maneuvering, staffing, naval history, and for now I don’t remember more, but the list is not complete!

Practice was required for all subject matters, exams, assignments and naturally written and oral examinations in February and final exams in June (in most cases both oral and written). Saturday afternoons were dedicated to class assignments; on rotation navigation, both optical and astronomical, quizzes (so called “the Americans”) in all professional subject matters.

General assembly for the reading of the “rewards and punishments”

Having completed morning classes and placed our books back into our school desks, at 1245 we had the “general assembly” for the three courses in the courtyard in the presence of the second in command or the third in command of the academy for the reading of the “rewards and punishments” by the “brigadier” cadet, meaning the head cadet of the third class (the only one wearing the “regular” uniform with a sword instead of a dagger). Here, whoever had been called to report finally knew the disciplinary sanctions he had “gotten”: one, two, or three days of confinement. One, two, three days of simple arrest, or the same or more of close arrest. In this last case, unofficially, the cadet was hinted to resign. At the end of the general assembly, still running, we moved on to the mess while the small group punished with arrests, under the orders of a non-commissioned officer in charge of the prison, moved toward “Villa Miniati”, a pompous nickname for the prison building which for many years had been managed by Chief Miniati.

Then the mess ceremony as in the morning but with two variations:

at 1300 we listened, while standing at attention to the world bulletin. Each table, in a special folder, would have mail addressed to the members of that table. But the mail could not be read. We could read it only after the “dismissed” outside the mess.

And we are at about 1330. Up to 1425: break. During this time, weather permitting, we could go sailing (star, jole, olympic beccaccini, dinghy), go to the reading room, play pool-table, play the hard fought “ugly ball” tournament (forerunner of the 5 man soccer and played with a different ball made out of old socks bundled up), or simply “graze”, that is to say stroll, sun bathe, read the mail, chit-chat with friends. Here were borne the “groups” made up of former schoolmates, people from the same town, new friends. New friendships were created or strengthened, links which were reinforced by common assignments to ships, or by being docked nearby, and which withstood the test of time, decades of ups and downs in life and, after 60 years, still hold up. Actually…

But let’s return to “my” academy. We were grazing: some sailing, some sunbathing, some in the reading room, others playing the “ugly” ball when at

1425 “the blow”. That is to say the trumpet signals which recalled us to the reality of everyday life. Two hours of intense activity as called for by each section: training with the assistant professors in some university-level subject matters, military training, and sports activities.

About sports activities, I should say that there was a requirement for all of us to pass a minimum number of disciplines, while those who had entered the academy with their own competitive experience, after passing the “minimal”, were required to participate in competitive activities between courses in their own disciplines. Swimming was a different issue. Here there was the requirement to pass the “minimum” for swimming, diving (and relative exercise, diving from a 5-meter platform). At that time fins and mask for scuba were not available and were utilized only by the special forces, thus underwater exercises were done in apnoea and without aids. The exercise were generally geared at giving us confidence in the water, thus at the end giving us a chance of survival in case of shipwreck. The swimming pool was considered the worst activity. First of all because we would die of cold (we would literally go in pink and come out purple), second because all, and I mean all without distinction for those who knew how and did not, we had to swim, without time limit, two laps (100 meters each), and dive from a 5-meter platform. For those who did not know how to swim, there was always someone in charge of the “rescue”.

Another athletic activity which did not spark enthusiasm was rowing “in a life boat with oars”. It would not create any envy to real prisoners!

Rowing “in a life boat with oars”.

But there were also some pleasant activities, sailing, kayaking, fencing, soccer, rugby, tennis (these last ones were only for those who had passed the minimal athletic requirements), shooting, scuba, “battle station exercise” on the brigantine. On average, once a month we would go out to sea aboard “old smoke crackers” for full navigational training. Astronomical navigational exercises with point fixing by sextant required a different ceremony; wake up before the others to be ready to make astronomical point fixing at the very first light of day, and wrap up calculations in time to take part regularly in the other morning activities. During the war, equestrian sports and judo were suspended

But let’s go back where we left. At 1645 “blow”. The trumpet called to an end the early afternoon activities. Sports break and then we would line up to receive the “sandwich”.

At 1645 all to the study. The “study” was a large room which could host, in separate tables, all the cadets. Monitoring was very strict. Always, one or two officers would walk between the rows of tables and there were no alternatives; with the mind, one could travel aboard ships, or go strolling with the girlfriend, but two things had to be done: keep the eyes open and the books open under the eyes. After all, there weren’t many alternatives; exams, assignments in class and after class, and the final examination forced the most turbulent not to get distracted. I was going to forget… before being released from study there were, on a rotational basis, drills with light signaling or with the horn, and naturally, with the most strict supervision! Once a week, each section interrupted studying for about 20 minutes to go take a shower (again, lined up and running). Studying continued until 1930 with a very short break at 1730 to use the toilet and smoke a cigarette (in those days we all smoked).

1945 Assembly for dinner. After dinner, a break until 2045 at the reading room, pool table, or singing (there was always someone who sang and we had a piano). Grazing was always indoor because in Leghorn, between the southwest and the north wind it was always cold at night.

2045 Assembly and running even up the stairways we would go to the dorms.

2100- 2130 Night routine and at 2130 all to sleep while the “silence” was being played. Since it was prohibited to own a watch (in those days objects of a certain value), the only sense of time at night was given by the inevitable striking of the hour from the bell tower. When, accidentally, one would go to the restroom at night and the clock was striking 0500 brrrr….only another half hour of sleep!

This was the usual day.

Variations: Wednesdays (Thursdays according to the course) and Sundays, after the break in the afternoon, we would go to the study until 1545 with the choice, alternatively, to write our families. During this time the “purser” non-commissioned officer distributed to those on short leave a small purse with 25 liras. During this period of study discipline was never relented. A classic case was the inspection officer saying, “You two down there who were talking. Stand up!” (An innocuous whisper between two desks). The two “under incrimination” would stand up. “Are you on short leave?” , “Yes, sir!” , “You were!”. Good-bye, short leave, until next week, if nothing else happened along the journey in the meantime.

At 1545 “short leave; change up!” We would go to the dorms where on our small beds the one on leave and only those on leave would find all the necessary wardrobe. Everything, and I mean everything, shined shoes, socks, shirt, starched collar, tie, etc.

1600 “Those on leave: line up!”, and then a very rigorous inspection. All it took was for the hair not to be super short and, good-bye leave. After the inspection, finally, we were free to swarm into Leghorn until 1945. Once back, we checked in and returned the purse with whatever was left of the 25 liras we had received before going on short leave. Without changing we would go to the evening assembly for dinner, and the cycle started again.

I must open a parenthesis about the financial management. Each family, as I have already mentioned, was required to send to the academy every three months a certain amount of money which included tuition, co-payment for uniforms, funds for the “purse”, money for drugs, books, refunds for damages caused (broken plates or glasses, altered hats, etc). Tuition and only tuition was reduced for particular family circumstances or for merit. The “purse” was managed independently by non-commissioned officers “pursers” and if by bad luck due to problems with the postal system the check from home was late in arriving and the balance for the purse was below 25 liras, the “purse” was not delivered and automatically one was confined.

In reference to “my” academy, I must include another topic which cannot be overseen: disciplinary sanctions, both individual and collective. Let’s start with the individual ones. The simplest were the “runaround” and the “go around”. They consisted of running loops like the bersaglieri light infantry around the courtyard (about 400 meters), or going up the mast of the brigantine from the right side, past the crow’s nest, continuing up to the bar just under the trunk, and then coming down the opposite side across the deck of the brigantine in time to go up again from the right side if the “go arounds” were more than one. These punishments were given verbally, meaning without going to report, and in number ranging from one to five, sometimes even ten, and had to be completed during the breaks. Thereafter, one would present himself to the officer who had assigned the penalty, of course standing at attention, saying “I completed …go arounds” to which followed the inevitable scolding. There were no controls but I believe that “reductions” (cheating) never took place. Self-discipline and fairness were an integral part of our professional formation, thus it was not conceivable to declare completed a punishment, which had not been fully done. More severe punishments consisted of confinement, arrest, and close arrest. These disciplinary sanctions were inflicted after having been called to report, as I’ve already narrated, and were read during the general assembly with the three courses lined up in the courtyard before going to lunch. The third in command, who was usually in charge of the general assembly, would say, “Attention to the reading of the compensations and punishments.” Compensations, in reality very rare, consisted of permission to extend short leave until 2100, dining out instead of returning at

1930. Thus they had most of all a moral value and were given generally when one had obtained the highest score during an exam or by winning an athletic competition. Arrests, like the confinements, were generally given out for reasons that today would really make us laugh. More than everything else, they were aimed at reciditivity in poor performances in studying and some minor disciplinary infractions. Close arrests, as already said, were a very different affair and were rarely inflicted due to the heavy weight they had. Confinements consisted of spending free time in the study. Arrest or close arrest were paid for in prison, “Villa Miniati”. The guests of this little villa had at their disposal a small room which included a small desk for study, and a fairly hard folding bed, but where, due to the power of the organization, the attendants would place the pajama for the night, blankets, and toiletries for each guest. No linen, though! In prison one spent the hours usually dedicated to meals, to free study and recreation. One did not miss lessons, nor training, nor class assignments. The difference between arrest and close arrest was practically none. It was the bearing on the scoring card which mattered. It did matter!

Collective disciplinary sanctions generally involved an entire section and consisted of a certain number of “go arounds” to be completed lined up, or even worse in 15 minutes or more on guard. What it meant was that the whole section had to stand still in the courtyard, “on guard” for the duration of the punishment. A real torture! I’ll skip what would cause disciplinary sanctions so harsh… Before wrapping up my answer, I must talk about some of the typical characters at the academy. First of all the non-commissioned officers; some served as instructors in professional activities and also athletic ones, others were simply in charge of the classes in regards to maintaining the discipline. I don’t know how they were selected, but all, and I repeat all of them, I remember with the greatest affection. Despite the fact that they had an ungrateful assignment (being in charge of discipline and prison), they always behaved toward us with extreme distinction and toughness. I shall say that they always considered us their sons, without considering that in a little time we could have met them again aboard but in reversed roles.

Another character typical of the academy were the “attendants”. The ones with whom we had the greatest contacts were the ones in charge of uniforms and those who served at the tables. To them, we were the “masters” and even if some parents were former cadets and had become admirals, for the attendants who had known them as cadets, they were “the master your father”. The attendant barbers? Inflexible. They did not let themselves be softened by any begging (girlfriend or parent visiting Leghorn) into being more indulgent with the cutting. Maximum length of the hair: 2 centimeters; freedom of choice for shorter lengths.

A special discussion should be dedicated to the officers. The hierarchy was quite extensive. The commanding admiral (nicknamed “the old bag”), the second in command and the third in command had very precise assignments and were unapproachable. With the commander of the class (one for each of the three courses), Commander or Captain (nicknamed the principal) and his assistants, Lieutenants or Sublieutenants, contacts were very numerous. They followed us in every activity; they were instructors for professional training. They watched us when we were in the study, but what to say about them? They came from one or more sinkings, a few days in a lifeboat, or recovering from wounds received in battle. Therefore, with wrecked nerves, impatient to return aboard, even if they had received multiple war decorations for military valor, none of them ever talked about their war actions.

I dwelled over so many details of the daily life, punishments included, to underline that although outside war, as we well know, ravaged, in the academy life continued in the most normal way. Thus arises the question; why?

The answer is simple: there could not be disruptions from what was the primary objective of our professional formation: discipline and honesty. Questionable educational methodologies, and today’s psychologists would have much to argue about it, but life test demonstrated that these methods were not completely erroneous. Much has been said about the strategic abilities of our military leadership. I don’t want to touch this topic, but keeping my comments restricted to the Navy, I can, without doubts, assert that never, and I repeat never, did officers, non-commissioned officers, or sailors tremble facing orders received and which often called for their, or their ships’ ultimate sacrifice.

This is the result of the constant hammering, education, discipline, and honesty taught to the future officers, and in the required proportions to non-commissioned officers and sailors.

In the academy we were not fed special speeches or doctrines. They “got us to work” studying and with discipline. We complainted but the mark which was imposed upon us demonstrated itself valid not only during the war, but also after, in our private lives. Distractions aside, back to “my academy”.

I told you, perhaps with too many details but in general terms, about my memories, my emotions, and part of my life as a cadet. Three topics are still missing: examinations, summer naval campaign, and the affairs of September 8th, 1943. Let’s begin with the examinations. As already mentioned, two rounds of exams for each academic year. Phase one in February, named the “chat”, but exams nevertheless. They covered the first half of each subject matter. Another round in June, but this differed from the previous one because the scope of each exam included what had been studied since the beginning of the year. Each session included ten to thirteen exams, some of which were both oral and written. The gap between each exam was at the most three days, thus the whole session lasted about a month. During the examinations some of the daily routine changed, but disciplinary rules did not change at all.

As everywhere, there were professors (for university level subject matters) and instructors (for professional subject matters); some very demanding, others more lenient. Failures rained frequently. I will not dwell on the misfortunes of those who were failed; anyway they were not the best. Failure meant passing a “catch up” exam; final failure meant repetition of the school year, just like in high school, or resignations to then continue the 5-year draft as a simple sailor.

At the end of each examining session, we left for the longed for vacation. Base program: sleep. Unfortunately, this was also time to come to grips with the reality of war. Cities bombed, homes destroyed, relatives or acquaintances missing, homeless families, shortage of food. We were 20 and wounds healed quickly.

Before talking about the summer naval campaign (the cruise), I must say that the war had caused a change to the three-year program. At the end of the second course, the summer cruise of three months aboard the training ships Vespucci or Colombo was no longer conducted. Instead, the cadets were sent for 20 days up to the mountains and at the beginning of August we would come back to Leghorn to begin classes for the third year. Therefore, we spared the time for the summer cruise and completed the third year in February, ready to be embarked.

Before covering the misfortunes of my course, which remain unique in the 120 years of history of the Naval Academy, I’ll tell you something about our training cruises aboard training ships. The cruise, we are in July-September 1942, for obvious security reasons took place in the Upper Adriatic; Fiume, the Dalmatian Islands, Zara, Pola. Navigation, was usually short and characterized by continuous turning in narrow waters, thus for us in charge of the sails it was very stressing. Aboard, life was quite Spartan and was made even worse by the very limited space assigned to each of us. A sailors’ life, a simple one, even if we were still served at the table in white gloves.

Spartan life I was saying. We slept on amacha which were strung at night above the tables on which we ate and studied, and did our calculations. We only studied professional subject matters, and we calculated over and over again astronomical coordinates based upon the early morning or evening’s twilight readings. That is 0400, 0500 and 1900 and 2000 at night. At that time, calculators did not exist and we did not have navigational systems. For rough calculations we used the slide rule, but perhaps you had never seen one. For astronomical calculations we used paper, pencil, and logarithmic tables which allowed us to simplify some of the calculations. In short, calculations of a navigational point required 45 minutes, and only when everything went right! “Action station” for the sail did not represent a great novelty to us.

The numerous exercises and the many “go up and around” on the brigantine interred at the academy made us relatively experienced and nonchalant about going up, lining up along the yard spar, and rolling out or wrapping up the sails. The difference was that the masts at the training ship were about 60 meters above the water, while those of the brigantine at the academy did not reach 30 meters. Also, while the deck of the brigantine was solidly anchored to the ground, those of the training ships swayed quite a bit according to sea conditions. A 15-story building moving about against a solid 7-story one. More dangerous? I should say no, even though at that time we did not have safety systems. But we never had serious accidents.

The only inconvenience was that the “go up and around” which had to be paid off at sea were longer and more annoying, and the “calls to station” were more frequent because the Dalmatian coast required frequent turning and we faced violent wind gusts. These were very insidious because they were canalized between the islands. They were so typical that our course was given the nickname “wind gusts”.

Of “my” academy in Leghorn and the time aboard the Vespucci (I was forgetting, between us of the Vespucci and “them” of the Colombo there was great rivalry), I believe I said the very least to answer your question. Buy for the “wind gusts” (in Italian the same word could mean a burst of machine gun fire), the academy was not only Leghorn the Vespucci and the Colombo.

At the end of March 1942 (I was attending the second course), the Allies began bombing Leghorn. Initially, targets were only strategic: shipyards, torpedo factories, refineries, the port. The academy in the beginning was not touched, but the cadets represented “goods” too valuable. Aboard ships they needed us to replace war losses. War events had created great vacuums amongst crew and we were still inexperienced, we represented oxygen for the ships. Thus, we could not be exposed to the danger of aerial bombardments. At the end of the school year, the first course went ahead of schedule aboard the training ships, and we of the second course, also ahead of schedule, were transferred to the mountains to take the final exams. At the end of the exams, after a small period of rest still in the mountains, we were transferred to Venice where in the meantime the academy had been transferred to begin the third course. Here were also summoned the attendees to the first course. We were lodged at the Hotel Excelsior and studied at the Casino where rooms had been transformed into classrooms. It was the normal life of the academy, even though there had not been enough time to organize a mini-academy. Lessons, training, exams, assignments, and punishments… everything just like in Leghorn, but it did not last long. The armistice of September 8th caught us by surprise.

We did not have much time to reflect on the enormity of the tragedy which had fallen upon Italy. We did not realize the level of collapse to which our armed forces had fallen. The morning of the 9th, at the general assembly “Go to your room, pick up some blankets, and leave all your belongings at the foot of your bed. The attendants will pick them up for you”. In Venice, there was a hospital ship that had been laid up, the Saturnia. It had been altered to repatriate Italian civilians and their families from our former colonies in East Africa. These were people who, at the beginning of the hostilities, used to live in those areas later occupied by the British and who had been interned in concentration camps. Along with the twin ship Vulcania, the Saturnia circumnavigated the African continent and after having disembarked its load of refugees in some Italian ports, had been laid up in Venice.

I don’t know how they were able to commission it so quickly, but in the first hours of September 9th we boarded the Saturnia. Not everything went well, but I’ll skip these details. At night the Saturnia left the dock and moved to leave Venice. Near the semaphore of the Lido, we received signal via flashes of lights (we all knew how to read them) that German motor torpedo boats were patrolling just outside. We turned around and returned to Venice. After 24 hours, that is the night of the 10th, the Saturnia sailed again and went out to sea. This time we did not encounter anything. We did not know where we were going; may be Taranto. We navigated the 11th and the 12th, zigzagging as it used to be done as a countermeasure to possible submarine attacks. The zigzagging had to be done following prescribed rules, but the Saturnia did not follow those rules at all. This zigzagging was decisive; at 1530 on the 12th the Saturnia ended up on a sandbank just off Brindisi.

In Brindisi there were no Germans, but the Allies had not yet arrived, while the royal family was there, along with the head of government Marshal Badoglio and the whole entourage. In Brindisi there used to be one of the two naval schools of the GIL (Italian Youth of the Littorio), which prepared teenagers both scholastically (high school) and under a seafaring viewpoint as if it were a pre-academy. The naval school, due to summer recess and the fall of fascism, was completely empty and it almost looked like it was there waiting for us. Even if uninhabited, it had classrooms, dorms, and kitchens. It even had a brigantine just like Leghorn.

After some attempts to free the Saturnia with the makeshift boats from Brindisi, we were disembarked and placed at the naval school. From Venice had come with us military and civilian instructors, and also the “attendants”. Thus, although with some differences from Leghorn, on September 14th, 1943 we restarted our third year with a tempo just like Leghorn. Lessons, exams, assignments, wake up calls at 0530, “patches” for the inevitable mending jobs. However, there were some differences.

First of all, hunger. Foodstuff was scarce and we were in our 20. Second difference, absolute absence of books and teaching material. This deficiency was remedied by the goodness of some instructors and some of us in taking notes and distributing them (as an example, I will show you my notes about underwater weapons). Third difference, we asked and obtained permission to participate in the first operational activities of our Navy alongside the Allies. Here war came close to home; in an evacuation of Italian personnel from Greece fell the first classmates of our course.

But let’s return for a short while to Brindisi. Lessons, as I told you, started again on a regular basis. Some subject matters were eliminated from engineering (but we were allowed to catch up in the 1948-49 upper course) and in January 1944, after the usual examinations, we found ourselves with the rank of ensign aboard ships which meantime had begun operating alongside the Allies.

Before leaving “my” academy, I must mention how, despite the events which we lived through in those months, there was no letting down of the strictness to which we were accustomed. Same rules, same discipline, same examinations, same final exams. Some of us were failed in one or more subject matters and those who did not make it continued on as non-commissioned officers. Here ends my answer to your question. I could have said “yes, life at the academy was hard, we studied much, and all wanted to go aboard to participate in the war”. I preferred describing and reliving with my memories life at the academy. Find yourself amongst these words the answer to your question. In essence, I did not find myself at the academy by accident. Actually, I entered the academy of my own free will when war had already begun by a few years, and when our Navy had already suffered a few blows. We knew that a tough life of sacrifice was awaiting us. We knew that once aboard our lives would have been even tougher and that we would have been asked, if necessary, to make even the extreme sacrifice. We accepted all of this with clear mind and much lack of patience. Events not wanted by us impeded our course to suffer the bloodshed which the previous courses had suffered. Nevertheless, we did our duties, trying to do the best of what was asked of us. In a small part, we also contributed to rebuilding our beloved navy.

So, one question arises. One which you did not ask me and that I shall ask myself: “Would you do it again? Would you make the same sacrifices?” The answer gives no room to interpretation: I would. Oh yes I surely would!”

Could you describe to us your activities after you left the academy?

My activity after I left the academy?

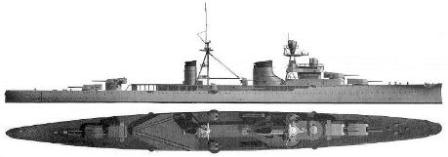

The whole course, deck officers, engineers, and weapon specialists were distributed aboard various units, and some volunteered in the San Marco and Bafile battalion fighting (unfortunately with wounded and dead) on land. Whoever was not assigned to a ship, most of us, received various other assignments. Some were sent aboard the battleships interned in the Bitter Lakes to replace young officers called to other assignments. There were those who were assigned to the cruisers operating in the Atlantic with base in Freetown. There were some who were assigned to destroyers conducting shuttle service with the ships of which I just spoke. There were others assigned to torpedo boats and corvettes. Some were sent to the submarines (unfortunately, one of our course mates died aboard the Settembrini). I was assigned to the corvette “Scimitarra”; initially as a subordinate to the navigation officer, and after having attended training course “A”, as a gunnery officer.

Which kind of activity did we do?

Mostly escort service for Allied convoys coming from Gibraltar or Malta that provided supplies for the frontline as this moved on. The dangers, even if lesser than those faced by our convoys to re-supply the Libyan or Tunisian front in the preceding years, were there and required much attention and seafaring skills. The convoys were many and the ships available for escort service few. Thus at sea, at sea, at sea; under all weather conditions, and at very low speed, still without radar, and with exhausting watches (the infamous four-and-four). We always attempted to keep the convoys in line, as if they were a flock of sheep. It should be considered that at the time the captains of merchant ships were less than good sailors. There was a bit of everything; lawyers, teachers, administrators, architects. After a short period of training of just a few months, they were made captains and off to sea, and the poor devils who were in charge of their escort had the task of keeping them in line, making them zigzag according to schedule, avoid hitting mine fields…and so on. All this, I repeat, without radar, in total radio silence, with ships completely darkened and with only the use of light signals. When we would arrive in ports such as Leghorn, where due to the ships sunk by the Germans the cargo ships could only enter with very calm sea, very slowly, and one at a time, the escort would be left off shore going back and forth to protect the convoy from frogmen attacks.

Recapping: these contributions made by our navy, onerous under a human and seafaring viewpoint, allowed the Allies to remove some of their ships from this activity, concentrating them in the Atlantic, but especially in the Pacific where the ever increasing amphibious operations required an ever increasing number of escort units.

This is what I did after I left the academy until the end of the hostilities when, if you will, the need for convoy escort ended. But… as I mentioned in my opening statement, for the Regia Marina the war did not end. With the end of the need for convoy escort was born the need to clean up the sea of numerous mines disseminated everywhere by Italians, Germans, and the Allies. The corvettes, affectionately nicknamed by me “the little maids of the sea”, were transformed into minesweepers and called to perform minesweeping duties. To fully answer your question, I tell you that, still on the Scimitarra, I participated in two long campaigns of mine clearing, the first in the area south of Salerno all the way down to Cape Palinuro, and the second, much longer, off Fiumicino (Rome) up to the Argentario Mountain (Tuscany). And then? Then for me this appendix to the world war ended in September 1946. I was called to other operational activities which are beyond the scope of your question. We were by then in full “post-war” period.

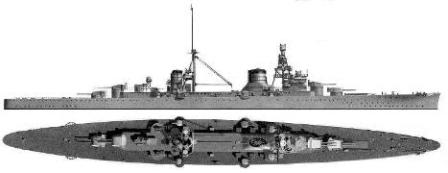

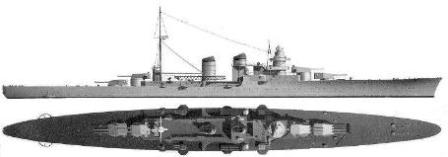

The history of the Italian Navy in World War Two has been characterized by extraordinary events such as the attack against Alexandria, as well as very controversial ones, such as the false sinking of Commander Grossi: in 100 years what do you think will be the historical interpretation that will be part of textbooks?

It is not easy to give an answer to your question because even if over 60 years has passed since those events, we cannot yet consider concluded both the research and the discovery of documents which would complete the knowledge of important events. Also, some new light may be shed on events about which we thought we knew everything. Research activity continues incessantly and the word “end” will be written, if ever, in many years from now.

The recanting of these events has gone from the protagonists to the journalists, from the memories of some of the protagonists to end up in the hands of the historians who, even though they are always very serious and objective, cannot avoid influencing their studies and researches with their own personality. What will end up in the textbooks? I would like to begin by describing what is now in the textbooks. I should in turn conduct a research since historians for scholastic material are few, of the most disparate political connotations, and influenced by the prevailing political wind in the country. Thus, even if not openly direct, some specific ministerial directives cannot be eluded. You know perfectly that one may say, and not say at the same time, thus putting together all the variables I just mentioned, you will understand that making an assumption of what the textbooks will look like in 100 years is a real mystery. Just to give you an example, I ask you “what is left in the textbooks of the war of independence and of the First World War?” Certainly the actions of our insidious weapons will still be spoken about, just like today we still talk about those of Luigi Rizzo, while the Mussolinian farce around the actions of Commander Grossi will be completely ignored. Luckily enough, it has been quite some time since this farce has completely disappeared.

I repeat and conclude by saying that those are just my conjectures and anyone could confirm or deny them. The appointment is in 100 years!

A special note:

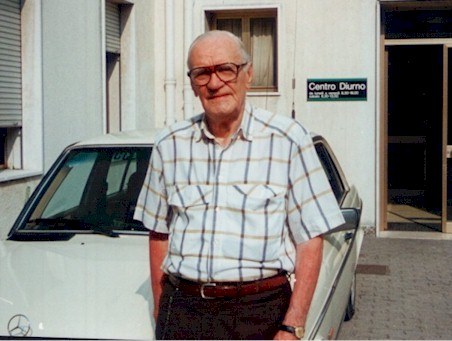

Due to distance – I live in California and Commander Romano lives in Rome – the interview took place over the Internet via email. Commander Romano contacted our site back in March 2000 offering some suggestions, and since he has been a personal mentor, a source of inspiration, and certainly a reason for persevering. For those of you who might be interested, Commander Romano entered the Academy in 1941 and completed his course in 1944. After a long period of active service, he left the Italian navy in 1960, but he never severed his links with the navy.